The Church League for Women's Suffrage

Claude was the first Secretary, and the renowned Dr Agnes Maude Royden

[left as a young woman, and in 1937 leaving Waterloo Station for the USA] was Chairman [sic]. Its object was to bind together, on a

non-party basis, Suffragists of every shade of opinion who are Church

people in order to secure for women the vote in Church and State, as

it is or may be granted to men. Its

methods were devotional and educational. CLWS members made special

intercessions for the League and its members at holy communion on the

first Sunday of the month. A committee was set up to prepare draft

recommendations for the revision of the Marriage Service in the Book

of Common Prayer. One reference book says that the end of 1913 it had

103 branches and 5080 members, but another gives the figure as 66

branches with 3000 members, including 5 bishops.

Claude was the first Secretary, and the renowned Dr Agnes Maude Royden

[left as a young woman, and in 1937 leaving Waterloo Station for the USA] was Chairman [sic]. Its object was to bind together, on a

non-party basis, Suffragists of every shade of opinion who are Church

people in order to secure for women the vote in Church and State, as

it is or may be granted to men. Its

methods were devotional and educational. CLWS members made special

intercessions for the League and its members at holy communion on the

first Sunday of the month. A committee was set up to prepare draft

recommendations for the revision of the Marriage Service in the Book

of Common Prayer. One reference book says that the end of 1913 it had

103 branches and 5080 members, but another gives the figure as 66

branches with 3000 members, including 5 bishops. | When

the procession reached Bond Street there was a long halt, and fearing

that the head of the procession would perhaps fill the church before

our section arrived ... I slipped out of the march, crossed to St.

James's Street, hailed a taxi and told the driver to drive to St.

George's Church, Bloomsbury. It'll cost you 3s. 6d. if I do, said this opportunist Jehu. Get on as quickly as you can,

I said and entered the taxi, and got as far as Holborn and the foot of

a side street leading into Hart Street where the church is situated. I

sprang out. Stop here, I said, and I'll walk through to Hart Street. I placed the money in his outstretched hand and vanished. On getting to Bloomsbury Street it was a packed mass of humanity, and how to cross it to get to the pavement on the side of the church I knew not. But to get to that church I was determined if it cost me what the cause had cost the woman whose obsequies we were celebrating. I literally swam my way to the pavement, pushing people aside right and left as a swimmer does the water. Among the hoarse cries of a community who had come to see the remains of one 'butchered to make their English holiday', poor victims of the social systems of 'civilization' in our great 'industrial' cities, who get so few real 'holidays'. The King's 'orse! they kept on bawling,The King's 'orse! Chuck 'er out, said one of my own sex: these Suffragettes always spoil everyfink, forgetting that one now dead was giving them an entertainment. I wriggled my way on to the pavement, and for about a hundred yards or more wriggled in between them and on to my goal, the King's 'orse ringing in my ears. At one point a tall rather fine looking man, of the red hair and freckle order, put his arm round me to protect me, and did so in such an offensive and obscene manner that I literally shrieked out: Oh, Christ, to think that you died for such as these! He withdrew his arm quickly and said sternly, Let her pass, and helped me on a bit. Arriving at the church there was a double row of policemen across the pavement defending its entrance, and on the steps was our devoted friend, the Rev. Claude Hinscliffe, who had formed the Church League for Women's Suffrage, and several other clergymen, all tense and with white faces and in white surplices, awaiting the cortege ... |

In

February 1914 the League rejected a

motion, proposed by its Worcester branch, that it should declare

itself opposed to militancy; as a result it lost a number of members.

Then came the war - but the work continued; as this letter [right] shows,

the CLWS supported the Serbian Relief Fund. In

the aftermath of the First World War, the Representation

of the People Act 1918

was passed, abolishing the property qualification for men and giving

the vote to women over 30 with minimal property qualifications. Full

female suffrage had to wait until 1928.

In

February 1914 the League rejected a

motion, proposed by its Worcester branch, that it should declare

itself opposed to militancy; as a result it lost a number of members.

Then came the war - but the work continued; as this letter [right] shows,

the CLWS supported the Serbian Relief Fund. In

the aftermath of the First World War, the Representation

of the People Act 1918

was passed, abolishing the property qualification for men and giving

the vote to women over 30 with minimal property qualifications. Full

female suffrage had to wait until 1928. As for women's rights in the church, in 1919 the Church

of England (Assembly) Powers Act

[commonly known as the Enabling Act] created the national Church

Assembly (the precursor of General Synod), with powers to pass

'Measures' which have the same authority as Acts of Parliament; it

paved the way for the creation of Parochial Church Councils in every

parish. As a result, women increasingly began to take their place in

local and national church governance, though it was a slow and

sometimes painful process!

As for women's rights in the church, in 1919 the Church

of England (Assembly) Powers Act

[commonly known as the Enabling Act] created the national Church

Assembly (the precursor of General Synod), with powers to pass

'Measures' which have the same authority as Acts of Parliament; it

paved the way for the creation of Parochial Church Councils in every

parish. As a result, women increasingly began to take their place in

local and national church governance, though it was a slow and

sometimes painful process!

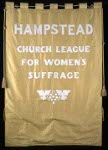

Several

branches had

fine banners, some of which are now housed in museums [left is the Hampstead one, designed by Laurence Housman and maybe worked by

his sister Clemence whom he described as 'chief banner-maker for the

Suffrage Atelier'].

The League's main banner, designed by Oswald Fleuss and made by the

Audrey School of Needlework, depicted St Margaret of Antioch.

Several

branches had

fine banners, some of which are now housed in museums [left is the Hampstead one, designed by Laurence Housman and maybe worked by

his sister Clemence whom he described as 'chief banner-maker for the

Suffrage Atelier'].

The League's main banner, designed by Oswald Fleuss and made by the

Audrey School of Needlework, depicted St Margaret of Antioch. After

the First World War CLWS was retitled the 'League of the Church

Militant' [right] and enlarged its horizons to include work for the ordination

of women. It produced a series of pamphlets (as well as various leaflets), including

After

the First World War CLWS was retitled the 'League of the Church

Militant' [right] and enlarged its horizons to include work for the ordination

of women. It produced a series of pamphlets (as well as various leaflets), including