Roman Catholic chapels and churches in the parish

In

Queen Anne's time there were said to be 20,000 Catholics in London, and

this was the figure given by the vicariate in the returns of 1746, but

numbers were beginning to increase. Although the Penal Laws,

prohibiting Roman Catholic worship, remained in force until the last

quarter of the 18th century, it was possible for wealthier Catholics

(who tended to live in Soho, 'Little Ireland') to attend various

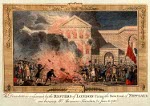

embassy chapels [right: Sardinian chapel, Lincoln's Inn Fields]

and 'mass houses' in Westminster and the City, and - though it was more

dangerous, even as attitudes relaxed - for the increasing number of

Irish immigrants to meet clandestinely in local chapels and

houses. A doorkeeper would check them in and lock the door,

giving a signal when it was safe for Mass to begin. Looking back to the

previous century, Mr Hodges in a Catholic Handbook of 1857 says not

long ago aged Catholics in this district were in the habit of speaking

of the bed in the priest's room, where they heard Mass, such an

appendage being considered a necessary protection against an intrusive

informer. See here for the 1746 trial of Thomas Sockwell, a wig-maker, for exercising part of the Office and Function of a Popish Priest at his home in Penitent Street, with prayers in Latin, crucifixes, 'wax images' and rosary beads - he was acquitted.

In

Queen Anne's time there were said to be 20,000 Catholics in London, and

this was the figure given by the vicariate in the returns of 1746, but

numbers were beginning to increase. Although the Penal Laws,

prohibiting Roman Catholic worship, remained in force until the last

quarter of the 18th century, it was possible for wealthier Catholics

(who tended to live in Soho, 'Little Ireland') to attend various

embassy chapels [right: Sardinian chapel, Lincoln's Inn Fields]

and 'mass houses' in Westminster and the City, and - though it was more

dangerous, even as attitudes relaxed - for the increasing number of

Irish immigrants to meet clandestinely in local chapels and

houses. A doorkeeper would check them in and lock the door,

giving a signal when it was safe for Mass to begin. Looking back to the

previous century, Mr Hodges in a Catholic Handbook of 1857 says not

long ago aged Catholics in this district were in the habit of speaking

of the bed in the priest's room, where they heard Mass, such an

appendage being considered a necessary protection against an intrusive

informer. See here for the 1746 trial of Thomas Sockwell, a wig-maker, for exercising part of the Office and Function of a Popish Priest at his home in Penitent Street, with prayers in Latin, crucifixes, 'wax images' and rosary beads - he was acquitted.| the Catholics of

the neighbourhood were accustomed to assemble on Sundays and holidays,

at a house in Branch-place, Cable-street; and obtained admittance by

producing tickets, which were occasionally changed to prevent the

intrusion of spies. Here the divine mysteries were offered up, and in

this house the holy sacraments were administered to the faithful. A

public house, the Windmill, in Rosemary-lane, was also converted into a

house of prayer, and here Catholics met and assisted at the holy

sacrifice of the mass, unsuspected by the pursuivant or by the informer. We now come to the Catholic chapel in Virginia Street. Strange as it may appear, this chapel owes its origin in great measure to the project of a Portuguese Jew, named Emanuel; this man represented himself to doctor Challoner, and to the embassador from the court of Portugal, as a Catholic priest, and by means of papers which he had surreptitiously obtained, passed for a considerable time unsuspected; through his exertions the chapel was erected and placed under the protection of the king of Portugal, whose arms were fixed over the principal entrance, and it assumed the name of the Portuguese hospital. Emanuel was afterwards discovered to be an impostor, he was consequently driven from the chapel, and some years afterwards died in the poor-house of Whitechapel, in a state of wretchedness and abject poverty. |

However, in 1780 Anti-Catholic sentiments were whipped up by the

arch-Protestant Lord George Gordon [right], whose mobsters destroyed many

places of worship, including the Virginia Street chapel, and the one in

Nightingale Lane, East Smithfield, as well as the Sardinian chapel []ipctured above] and those around Moorfields. To his shame, the Secretary of State

had instructed priests to dissuade their Irish parishioners to stay

away, for their own safety, and avoid exacerbating the disturbances. Fr

Coen reported that he had complied with this, even though (as he

reported to Hodges) he could have

could have assembled, within the space of one half-hour, 3000 men from

amongst the ballast-getters, coal-heavers, etc., and by their

assistance have protected the chapel; but he thought it right rather to

yield to the wishes of the Government. One of the clergy, who remained

upon the spot to the last extremity, with difficulty escaped from the

infuriated mob.

However, in 1780 Anti-Catholic sentiments were whipped up by the

arch-Protestant Lord George Gordon [right], whose mobsters destroyed many

places of worship, including the Virginia Street chapel, and the one in

Nightingale Lane, East Smithfield, as well as the Sardinian chapel []ipctured above] and those around Moorfields. To his shame, the Secretary of State

had instructed priests to dissuade their Irish parishioners to stay

away, for their own safety, and avoid exacerbating the disturbances. Fr

Coen reported that he had complied with this, even though (as he

reported to Hodges) he could have

could have assembled, within the space of one half-hour, 3000 men from

amongst the ballast-getters, coal-heavers, etc., and by their

assistance have protected the chapel; but he thought it right rather to

yield to the wishes of the Government. One of the clergy, who remained

upon the spot to the last extremity, with difficulty escaped from the

infuriated mob.

The Riots were a complex phenomenon. They began with a march to

Parliament to deliver an anti-Catholic petition, and resulted in five

days of mayhem, not helped by the lack of a proper police force, and

only finally quelled by the army. In the process they became a vehicle for wider

working-class grievances. Convicts were liberated from Newgate

Prison (now the Old Bailey), and The Clink (which never re-opened); impressed sailors

were set free from 'crimping houses' and debtors from 'sponging

houses'. A few of London's emerging black population were

involved, including the former slaves John Glover, described as a copper coloured person, who was seen torching Newgate with the cry Damn you, open the gate or we will burn you down and have everybody out, and Benjamin Bowsey - see more here. The house of Lord Mansfield, the Lord Chief Justice (see above) was also attacked.

The Riots were a complex phenomenon. They began with a march to

Parliament to deliver an anti-Catholic petition, and resulted in five

days of mayhem, not helped by the lack of a proper police force, and

only finally quelled by the army. In the process they became a vehicle for wider

working-class grievances. Convicts were liberated from Newgate

Prison (now the Old Bailey), and The Clink (which never re-opened); impressed sailors

were set free from 'crimping houses' and debtors from 'sponging

houses'. A few of London's emerging black population were

involved, including the former slaves John Glover, described as a copper coloured person, who was seen torching Newgate with the cry Damn you, open the gate or we will burn you down and have everybody out, and Benjamin Bowsey - see more here. The house of Lord Mansfield, the Lord Chief Justice (see above) was also attacked. | 1808, August. Much disturbance at Virginia Street Chapel, between the Committee and Chaplains of the said Chapel, concerning the alterations of the Chapel and the music introduced into the choir. The same being inflamed and at last breaking into an absolute fall out, Chaplains against Committee, I assisted at the Committee held on 25th inst., and reconciled both parties. Those who had used intemperate language at former meetings arose and begged pardon publicly for the same and for the offence they had given. Peace and harmony were restored. May discord never enter more among them! ... Mr. Berger, a German, having acquired a large fortune by success in business, made a present of more than twelve hundred pounds to Virginia Street in gratitude to Almighty God for granting him that success, and by this money the alterations in the Chapel were made and an organ and High Mass were introduced. |

The Society of Charitable Sisters

The Society of Charitable Sisters| Times have changed very much, and we are not insensible to the

exertions of those liberal, enlightened statesmen, that brought about

the change. We have now a large chapel at Moorfields, which all the

world (!) frequent, and where, for years, the truths of religion have

been without fear announced ... Virginia Street, once an hospital

for foreign sailors, was at first nothing more than a room for the

priest. This has swelled into one of the most capacious chapels in

London; and the few that knelt and prayed in the priest's room, to hear

mass, has increased to the ten thousand of the actual present

congregation. |

|

VIRGINIA-STREET, Ratcliff-highway.—Mass every day at 10 o'clock; on

festivals of obligation at 8,10, and 12 o'clock; on Sundays at 8, 9,

10, and 11 o'clock. A discourse after the Gospel at High Mass. Vespers

at 3 o'clock on Sundays only, after which catechetical

instructions.—Chaplains, Rev. Messrs. Richard Horrabin, James Foley,

and James Doyle. The Chaplains of Virginia-street Chapel, are the spiritual directors of the East London Catholic Charity Schools, and have daily to attend the London Hospital, Mile-end-road, the receptacle of all accidents in the docks, wharfs, and ships, from Black-wall to London Bridge, as well as fifteen workhouses; the chief of which are St. George's in the East, Wapping, Ratcliff, Stepney-green, Aldgate, Crutched-friars, Barking, St. Dunstan's, and St. Olave's. N.B. The Boys' School is now under the superintendence of two Christian Brothers, and contains seats for 180 Boys. The girls' school will accommodate 200 children. The late change and consequent alterations, &c., have involved the managers in a considerable debt, which, with the strictest economy, it will take them a long time to liquidate, unless some kind friends of the charity should come to their assistance, which God grant. Vide notice of these Schools in the sequel. |

English Martyrs Church was

built in Prescot Street in 1876

to designs by Pugin, with mosaics by Arthur Fleichmann. It had a branch

of the Catholic Social Union (founded in 1893 by Cardinal Vaughan), led

in the 1890s by

the Dowager Duchess of Newcastle, who having no home ties to hinder

her came to settle for a time with two Catholic ladies who had started

a girls' club, at what became known as 'Gertude House' in nearby St

Mark's Street. She wrote about her experience in the Pall Mall Magzine 1903 (vol 29, p454). English

Martyrs' Primary School - replacing Tower Hill RC Primary in Chamber Street [hall right, after closure] - is now behind the church, close to the site of

the former St Mark's church, designed by Broadbent, Hastings, Reid & Todd (1969); pictured is the procession at its opening by Cardinal Heenan in 1970, in South Tenter Street. Here

are

pictures of parish events from the 1930s to the present day.

English Martyrs Church was

built in Prescot Street in 1876

to designs by Pugin, with mosaics by Arthur Fleichmann. It had a branch

of the Catholic Social Union (founded in 1893 by Cardinal Vaughan), led

in the 1890s by

the Dowager Duchess of Newcastle, who having no home ties to hinder

her came to settle for a time with two Catholic ladies who had started

a girls' club, at what became known as 'Gertude House' in nearby St

Mark's Street. She wrote about her experience in the Pall Mall Magzine 1903 (vol 29, p454). English

Martyrs' Primary School - replacing Tower Hill RC Primary in Chamber Street [hall right, after closure] - is now behind the church, close to the site of

the former St Mark's church, designed by Broadbent, Hastings, Reid & Todd (1969); pictured is the procession at its opening by Cardinal Heenan in 1970, in South Tenter Street. Here

are

pictures of parish events from the 1930s to the present day.<< History