Arthur Bailey

The

architectural practice of Ansell and Bailey was established in 1900.

Today it has offices in London and Manchester, and works mainly in the

healthcare, education, sport and leisure and commercial sectors,

both in the UK and abroad. Arthur Bailey was a partner until his

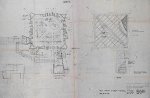

death in 1979, and specialised in church work. He prepared many

drawings for the scheme at St

George-in-the-East, some more radical than others, including one with a

central altar surmounted by a baldacchino (our thanks to Ansell and

Bailey for permission to include these drawings). It would be good to know how

the final choice was made.

The

architectural practice of Ansell and Bailey was established in 1900.

Today it has offices in London and Manchester, and works mainly in the

healthcare, education, sport and leisure and commercial sectors,

both in the UK and abroad. Arthur Bailey was a partner until his

death in 1979, and specialised in church work. He prepared many

drawings for the scheme at St

George-in-the-East, some more radical than others, including one with a

central altar surmounted by a baldacchino (our thanks to Ansell and

Bailey for permission to include these drawings). It would be good to know how

the final choice was made.

Arthur Bailey did innovative work renewing bomb-damaged churches in London. One of the first was the Dutch Church,

Austin Friars - the oldest Dutch-language Protestant church in the

world. Blitzed in 1940, it was rebuilt from 1950 to Bailey's designs,

as a concrete box frame clad in Portland stone. It was listed (Grade II) in 1998.

Arthur Bailey did innovative work renewing bomb-damaged churches in London. One of the first was the Dutch Church,

Austin Friars - the oldest Dutch-language Protestant church in the

world. Blitzed in 1940, it was rebuilt from 1950 to Bailey's designs,

as a concrete box frame clad in Portland stone. It was listed (Grade II) in 1998.

Another was St Nicholas Cole Abbey,

a Wren church gutted by fire in 1941 [left in 1946 - as a ruin, it was the backdrop for a bullion robbery in the 1951 film The Lavender Hill Mob] and

rebuilt to plans by Arthur Bailey in 1961-62 as a near-facsimile but

with a taller spire. Burne-Jones' east windows were replaced with

Chagall-like glass by Keith New (1925-2012) [fourth left], who also produced work for Coventry

and - via St Stephen Walbrook - Norwich cathedrals, and this

large window for the new housing estate church of St John Ermine in

Lincoln. From 1982-2003 the Free Church of Scotland used the church,

and from 2006 the Culham Institute

occupied it as an RE centre; it is now re-launched as a centre for

'Bible-based workplace ministry' - St Nick's Talks - under the aegis of St Helen

Bishopsgate, as one of the Capital VIsion 2020's

commitment to establish a hundred new worshipping communities in the

diocese, though it is not a parish or guild church as such.

Another was St Nicholas Cole Abbey,

a Wren church gutted by fire in 1941 [left in 1946 - as a ruin, it was the backdrop for a bullion robbery in the 1951 film The Lavender Hill Mob] and

rebuilt to plans by Arthur Bailey in 1961-62 as a near-facsimile but

with a taller spire. Burne-Jones' east windows were replaced with

Chagall-like glass by Keith New (1925-2012) [fourth left], who also produced work for Coventry

and - via St Stephen Walbrook - Norwich cathedrals, and this

large window for the new housing estate church of St John Ermine in

Lincoln. From 1982-2003 the Free Church of Scotland used the church,

and from 2006 the Culham Institute

occupied it as an RE centre; it is now re-launched as a centre for

'Bible-based workplace ministry' - St Nick's Talks - under the aegis of St Helen

Bishopsgate, as one of the Capital VIsion 2020's

commitment to establish a hundred new worshipping communities in the

diocese, though it is not a parish or guild church as such.

When the diocese of Sheffield was created in 1914, and the First

World War came to an end, plans were drawn up by Charles Nicholson to

enhance the old parish church for its new status as a cathedral. The

intention was to turn the orientation of worship through 90 degrees,

with a new chancel

and sanctuary to the north, with a second tower and spire, and a new

nave to the south. Some of the work on the north, including chapels,

offices and the Song School, was completed in the 1930s, but work

stopped with the outbreak of the World War Two and the funds were deployed

elsewhere. The change

of axis was abandoned in the 1960s in favour of a new plan to extend

westwards with a narthex entrance and lantern tower, to designs by

Arthur Bailey, in a style combining gothic with modernism seeking to be sensitive to what

is an architecturally mixed and complex building. The work was

completed in 1966. The lantern was glazed by Keith New

but, as at Blackburn Cathedral, the resin-bonded appliqué technique

failed and the glass was removed as unsafe; it was eventually reglazed

in the late 1990s by Amber Hiscott in a more abstract design [right].

There are currently further plans for the west end, for level access

and lightening the entrance, for a new font and hopefully a west-end

organ.

When the diocese of Sheffield was created in 1914, and the First

World War came to an end, plans were drawn up by Charles Nicholson to

enhance the old parish church for its new status as a cathedral. The

intention was to turn the orientation of worship through 90 degrees,

with a new chancel

and sanctuary to the north, with a second tower and spire, and a new

nave to the south. Some of the work on the north, including chapels,

offices and the Song School, was completed in the 1930s, but work

stopped with the outbreak of the World War Two and the funds were deployed

elsewhere. The change

of axis was abandoned in the 1960s in favour of a new plan to extend

westwards with a narthex entrance and lantern tower, to designs by

Arthur Bailey, in a style combining gothic with modernism seeking to be sensitive to what

is an architecturally mixed and complex building. The work was

completed in 1966. The lantern was glazed by Keith New

but, as at Blackburn Cathedral, the resin-bonded appliqué technique

failed and the glass was removed as unsafe; it was eventually reglazed

in the late 1990s by Amber Hiscott in a more abstract design [right].

There are currently further plans for the west end, for level access

and lightening the entrance, for a new font and hopefully a west-end

organ.

Arthur Bailey's most radical design to achieve fruition was the new

church, built

in 1963, of Holy Trinity Twydall Green, in suburban Giillingham. Its

future has become problematic. Plans were made to demolish it

and redevelop the site, but it was recently spot-listed (Grade II),

mainly at the instigation of the Twentieth Century Society supported by

local residents. It remains to be

seen if can attract grants for repair and insulation of the roof. The

Twentieth Century Society comments [links added]:

Arthur Bailey's most radical design to achieve fruition was the new

church, built

in 1963, of Holy Trinity Twydall Green, in suburban Giillingham. Its

future has become problematic. Plans were made to demolish it

and redevelop the site, but it was recently spot-listed (Grade II),

mainly at the instigation of the Twentieth Century Society supported by

local residents. It remains to be

seen if can attract grants for repair and insulation of the roof. The

Twentieth Century Society comments [links added]:| Built in 1963, the striking

cedar-clad pointed roof with a window split through is

undeniably inspired by Scandinavian post-war churches, notably the

Hyvinkään Kirkko by Aarno Rusuvuori in Finland (1961). The

roof is grounded by thick brick walls that protrude and

retract around deep-set windows, bringing to mind Le

Corbusier’s Ronchamp de Notre Dame. Their sloping coarse brick

surfaces (originally intended to be whitewashed) are designed

to represent the ground from which they break. The

building appears to erupt out of the ground, like a budding

plant in spring. Inside the church, the square plan and diagonally-canted pews mark the adaptation to centrally

orientated liturgical practice. The architect, Arthur Bailey,

is better known for his austere Dutch Church in Austin

Friars, London and restoration of blitzed churches, including

Hawksmoor’s St George’s in the East. Quite what

compelled such an otherwise conservative designer to embrace

such a modern and sculptural form is a mystery, and we can

only speculate that he was inspired by travels abroad or a

fresh influence in the studio. |

| PROPHET IN STONE Arthur Bailey died rather suddenly at Bournemouth, after seeming to be on the mend from a long illness which caused him to retire some ten years ago. He was an architect whose work covered a wide field: bridges over motorways and along them, churches in a wide variety of styles - the extension of Sheffield Cathedral - a wonderful design for Liverpool Roman Catholic Cathedral which took third prize and unfortunately did not go beyond the drawing board. St George-in-the-East did. It reflects the genius of a devoted Christian who said often that his sense of privilege in being asked to build and re-build or restore the house of God brought out the best skills and gave real satisfaction to him. BOWED HIS HEAD Those of us who watched him and worked with him on St George's for four years realised that the keystone of his success was a dedication that was spiritually alive. On each visit to the site he would stand where the altar was to be with bowed head, quite alone, seeking grace to know how to achieve this unique restoration. Later, when the altar stood and the very heart of the magnificent chancel, he stood in characteristic attitude, no doubt with thoughts of gratitude in his own heart for making a vision come to life. At the rededication the camera caught him with head bowed in the courtyard with the Bishop of London and the officers and friends of St George's. HAWKSMOOR - IN MODERN IDIOM Prophets down the ages have seen visions of God and translated the spiritual message into human language. Arthur Bailey, the author of the restoration of St George-in-the-East, did the same for the house of God in forms of stone, wood, glass and glorious line. The theme of his thinking for at least five years prior to 1964: "We must use modern materials in the idiom of Nicholas Hawksmoor." His rest at the end of a life so rich in the cultivation of spiritual values in architecture is well earned. We can assure his wife Phil and his son Martin, Carol and the girls of our gratitude and sympathy. He will live on in at least one of his great achievements. Tens of thousands of people who have admired St George's "rise up and call him blessed". |

Arthur Bailey's son Martin [left with the wardens, Nora Solomon, Canon John Cullen and Maxwell Hutchinson] attended

the service marking the 40th anniversary of the rededication of the

church. The 50th anniversary coincided with Easter, St George's Day and

the annual parochial meeting, but we kept it anyway (with several

people present who had been at the rededication, and shared their

memories), with further celebration as the July parish barbecue.

Arthur Bailey's son Martin [left with the wardens, Nora Solomon, Canon John Cullen and Maxwell Hutchinson] attended

the service marking the 40th anniversary of the rededication of the

church. The 50th anniversary coincided with Easter, St George's Day and

the annual parochial meeting, but we kept it anyway (with several

people present who had been at the rededication, and shared their

memories), with further celebration as the July parish barbecue.Back

to Church and Churchyard