Click

on these two images for details of the walk which celebrated the 300th

anniversary of the Fifty New Churches Act of 1711, and for details of

ongoing fundraising for these churches through the National Churches

Trust.

Click

on these two images for details of the walk which celebrated the 300th

anniversary of the Fifty New Churches Act of 1711, and for details of

ongoing fundraising for these churches through the National Churches

Trust.THE CHURCH BUILDING

Then...

Built and fitted out between

1714 (when a site was bought for £400) and 1729, St George-in-the-East was one of fifty new

churches planned for London (though only twelve were completed) - the

background to the scheme is explained here. Christopher

Wren (Upon the Building

of National Churches)

stressed their Protestant, and auditory, function - unlike the European

baroque churches of the time designed for the 'distant murmuring of the

Mass' - which he said meant a maximum of 2,000 seats, including

galleries; and they should be cheap.

Built and fitted out between

1714 (when a site was bought for £400) and 1729, St George-in-the-East was one of fifty new

churches planned for London (though only twelve were completed) - the

background to the scheme is explained here. Christopher

Wren (Upon the Building

of National Churches)

stressed their Protestant, and auditory, function - unlike the European

baroque churches of the time designed for the 'distant murmuring of the

Mass' - which he said meant a maximum of 2,000 seats, including

galleries; and they should be cheap.

But

St George-in-the-East (designed to

seat 1,230) was not cheap - it cost £18,557 3s. 3d. [another account

gives the figure of £23,832]. There were many

delays - bad bricks, workmen removed to other projects and also,

claimed the contractors, because local criminals stole the

building materials, 'especially on Sundays'.

But

St George-in-the-East (designed to

seat 1,230) was not cheap - it cost £18,557 3s. 3d. [another account

gives the figure of £23,832]. There were many

delays - bad bricks, workmen removed to other projects and also,

claimed the contractors, because local criminals stole the

building materials, 'especially on Sundays'.

A strong and magnificent pile, said the Grub Street Journal of 1734, which

commands the attention of all judicious observers, especially the

chancel end, which is truly magnificent. The frontispiece of the

tower is of the Ionic order, consisting of four pilaster, supporting

their entablature, wherein simplicity and grandeur are well connected

together. But another wrote the

strange ponderous walls of the church and steeple cannot be described

for want of terms. The wondows are that of a prison ... The inside of

the church is of the Doric order, and contains two pillars on each side

with a monstrous intercolumniation. In fact, Ionic or Doric (or both), it

is arguably the most original of the six London churches designed by

the idiosyncratic

architect Nicholas Hawksmoor.

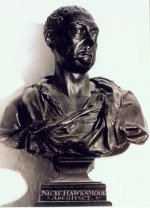

Little is known of his personal life: he was born in 1661 (or maybe

earlier) and died in 1736 of 'gout of the stomach', either at Millbank or at East Drayton, Notts. This bust,

by the sculptor John

Cheere (1709-87),

is the only surviving image of him - it sits on a lowly shelf in the

buttery of All Souls' College Oxford (which college he designed). He was self-educated, working as Wren's domestic clerk (rather a talented clerk,

said Sir John Betjeman) from the age of 18, and he never travelled

abroad - so his vast knowledge of classical architecture all came from

books and drawings, and his converse with Wren. His six churches are, in order (each is

comprehensively documented elsewhere):

Hawksmoor probably had a hand in the 1732 obelisk spire of St Luke Old Street; and certainly, in a very different style, in the gothic west front of Westminster Abbey. Outside London, he worked with Vanburgh on a number of large secular projects.

As former Rector Gillean Craig points out, it is instructive to compare St George's with the two other East End churches which were built simultaneously, Spitalfields and Limehouse: all share similar dimensions, all are heroic in scale and detail, all have great west towers, all bear the tension between central and axial plans, all are (or in our case were) built above huge vaulted crypts suspiciously well lighted for mere burial vaults.

Hawksmoor has been 'rediscovered' in recent years, both as a major architect and also as the subject of myth. (One of the pupils in Alan Bennett's The History Boys is questioned about his life and work.) In the 1960s, the architectural critic Ian Nairn wrote that St George-in-the-East represented the more than real world of the drug addict's dream. Hawksmoor figured in the speculative writings of Iain Sinclair, whose poem 'Nicholas Hawksmoor: His Churches' in Lud Heat (1975) links his churches to theistic satanism. Peter Ackroyd developed this line in a 1975 'magic realism' novel Hawksmoor (later made into a film) where the architect becomes a fictional devil-worshipper, Nicholas Dyer, and 'Hawksmoor' a 20th century detective investigating a series of murders in his churches. And Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell's novel From Hell speculates that Jack the Ripper used Hawksmoor churches for ritual magic and human sacrifice (they had corresponded with Sinclair).

These may be

good

stories, but to

portray his churches as centres of gloom and mystery, full of occult

and morbid

energies and pagan symbols, linked to ancient lay lines and

contemporary local murders, is untrue: silly nonsense as art critic

Waldemar Januszczak described it in his 2009 BBC Four series Baroque! Hawksmoor

was indeed a restless spirit,

drawing inspiration from diverse sources – Roman, Greek,

Egyptian,

Gothic – for which he faced rejection from his less-able

contemporaries. It was certainly an unusual choice to top St George's

Anglican tower with six circular Roman sacrificial altars - which the

architectural historian Dr Julian Litten (and leading expert on funeral customs - see The English Way of Death 1991) mischievously suggests would

make a fine crematorium chimney! - but this is eclectic rather than

subversive. His churches are fantastical and monumental essays in

stone, but not

in coded satanism. In fact he was seeking to recover for the national, established church a pure and

primitive

style of architecture –

which

he believed (wrongly, as we now know) stemmed from the Jewish

temple.

These may be

good

stories, but to

portray his churches as centres of gloom and mystery, full of occult

and morbid

energies and pagan symbols, linked to ancient lay lines and

contemporary local murders, is untrue: silly nonsense as art critic

Waldemar Januszczak described it in his 2009 BBC Four series Baroque! Hawksmoor

was indeed a restless spirit,

drawing inspiration from diverse sources – Roman, Greek,

Egyptian,

Gothic – for which he faced rejection from his less-able

contemporaries. It was certainly an unusual choice to top St George's

Anglican tower with six circular Roman sacrificial altars - which the

architectural historian Dr Julian Litten (and leading expert on funeral customs - see The English Way of Death 1991) mischievously suggests would

make a fine crematorium chimney! - but this is eclectic rather than

subversive. His churches are fantastical and monumental essays in

stone, but not

in coded satanism. In fact he was seeking to recover for the national, established church a pure and

primitive

style of architecture –

which

he believed (wrongly, as we now know) stemmed from the Jewish

temple.

Authoritative assessments of

Hawksmoor's work are to be found in John

Newenham Summerson’s classic Georgian

London (first ed. 1945, current ed. Yale University Press

2003) - he was one-time Curator of the Sir John Soames' Museum in

Lincolns Inn Fields, and wrote of their gloomy grandeur that approaches the

monstrous - and Kerry Downes' Hawksmoor

(Thames & Hudson 1970), who speaks of the ability of

Hawksmoor's churches to fascinate

the eye and disturb the memory. Architectural historian

Professor Vaughan

Hart introduced new material about Hawksmoor in his award-winning Nicholas Hawksmoor: Rebuilding

Ancient Wonders (Yale UP 2002).

More

speculatively, Pierre de la Ruffinière

du Prey, in Hawksmoor's

London Churches: Architecture and Theology

(Chicago University Press

2000) suggests that, in contrast to his city and West End churches,

for the East End he developed a kind of 'architectural

cockney',

powerful and direct, just like the common Greek of the gospels. Du Prey

also explores Hawksmoor's 'primitive Christian' ideas - see here for comment on his original drawings for the site, to include subsidiary buildings at each corner.

To quote Gillean

Craig again: St

George's has a uniquely complex skyline. As well as the western tower

there are four 'pepperpot' turrets, each large enough to form the tower

of an ordinary church. These had some practical excuse: each marks the

position of a spiral staircase that originally led to the great

galleries [they now lead to the church flats; the elaborate

detailing around their narrow entrance doors is extraordinary - pictured right]. There were no less than nine

doorways into the church [the four

flights of steps that

now lead down to the crypt level originally led up into the church,

through doors where now there are windows - see this picture of steps leading up to the vestry door]

... with separate entrances for the different classes according to

their ability to pay for better or worse seats. Nowadays the

façades, which reward extended study in their massing and

detail, appear perverse and wilful, but originally they signalled the

original interior disposition of the worship space with great clarity -

a spatial exercise of great boldness.

To quote Gillean

Craig again: St

George's has a uniquely complex skyline. As well as the western tower

there are four 'pepperpot' turrets, each large enough to form the tower

of an ordinary church. These had some practical excuse: each marks the

position of a spiral staircase that originally led to the great

galleries [they now lead to the church flats; the elaborate

detailing around their narrow entrance doors is extraordinary - pictured right]. There were no less than nine

doorways into the church [the four

flights of steps that

now lead down to the crypt level originally led up into the church,

through doors where now there are windows - see this picture of steps leading up to the vestry door]

... with separate entrances for the different classes according to

their ability to pay for better or worse seats. Nowadays the

façades, which reward extended study in their massing and

detail, appear perverse and wilful, but originally they signalled the

original interior disposition of the worship space with great clarity -

a spatial exercise of great boldness.

We

believe that St George's, with these distinctive pepperpot turrets,

presents a friendly face to the Highway, Docklands Light Railway and

the local

community. Pepper give spice and zest to life, and shaking it

about

is a good symbol of our task as the church. Using a similar metaphor,

the Bishop of London has called us ‘St

George-in-the-Yeast’!

We

believe that St George's, with these distinctive pepperpot turrets,

presents a friendly face to the Highway, Docklands Light Railway and

the local

community. Pepper give spice and zest to life, and shaking it

about

is a good symbol of our task as the church. Using a similar metaphor,

the Bishop of London has called us ‘St

George-in-the-Yeast’!

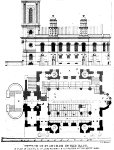

Externally,

the major change to Hawksmoor's vision was the entrance steps, which

date from around 1800. Previously, as the drawing on the left and the

plan below show, the circular

walls of the rotunda hid paired steps to north and south. The pilasters

that now butt up against the steps (whose slope came later!) were

originally conceived, in a typical Hawksmoor conceit, to be

read as the bases

of the great pilasters of the tower beyond.

These drawings from The Builder of 28 May 1915 were measured and drawn by Frederick J. Stephens. A wooden model of the church [right] is on permanent loan to the RIBA.

.and now

In May 1941 St George's was severely damaged by an incendiary bomb during the Blitz, leaving only the outer walls, vestry, Lady Chapel, the 160’ tower and all the turrets. All the interior was burnt, except for the still visible fire-shattered fragments of the capitals of pilasters on the east and west walls. Legend has it that one pair of cherubic heads in the apse plasterwork survived the Blitz - the rest is a faithful replica of the original.

So

the church

shared in the suffering of the

people of London, honoured to bear its scars to the present day - it

would have been a tragic mistake to allow it to become a controlled

ruin,

as some suggested!

For a time, worship was

conducted in the Rectory and Mission Hall, and then for seventeen years

in a prefab within the shell, known as St George-in-the-Ruins.

What

you see now is a paradox: within the proud Hawksmoor shell is a

modest worship space, designed by Arthur

Bailey

and reconsecrated in

1964. See here for some of his

many drawings for the project, and also

pictures of his other work, including other bomb-damaged buildings, an

extension to Sheffield Cathedral, and a new church at Twydall Green, currently under threat. Here is a brief architectural assessment of the project from The Times in 1959.

What

you see now is a paradox: within the proud Hawksmoor shell is a

modest worship space, designed by Arthur

Bailey

and reconsecrated in

1964. See here for some of his

many drawings for the project, and also

pictures of his other work, including other bomb-damaged buildings, an

extension to Sheffield Cathedral, and a new church at Twydall Green, currently under threat. Here is a brief architectural assessment of the project from The Times in 1959.

It is approached from an open

courtyard

where the nave once

was – a good space for various activities. From there you

enter a

light, airy and prayerful space, focused on elements of the surviving

semi-circular apse, with a full-height glazed window, good for looking

both inwards and outwards. It is eminently 'fit for purpose', and many

people find it an oasis of tranquility. We find it sad that some

visitors, guidebook in hand, ascend the steps into the courtyard and

twenty seconds later turn on their heels and depart, instead of

entering and engaging with a space that is historically and

theologically significant.

Some

(most recently Colin Amery, in a Royal Academy of Arts lecture in

October 2009) continue to argue that the 1960s work was merely a

temporary expedient in cash-strapped times, and that re-creation of a complete Hawksmoor

interior should yet be attempted. It was not, and such an exercise could

only be a speculative fantasy producing an unsustainable building of

limited usefulness, either for worship or community purposes, and

failing to honour the complex ongoing history of the church. (Amery had written in similar vein in 1991, supporting the ambitious but unsuccessful scheme by Stanton & Williams - his views are here.)

Others,

such as Dr Julian Litten (who was a member of the

working party considering the future of the church in the 1980s),

recognise that the 1960s intervention has its own integrity, and forms

part of the undervalued story of post-war church building - though that

is not to rule out future adaptation of the church and ancillary rooms,

as has already happened with the crypt. In this

article on Hawksmoor, Gavin Stamp of the Twentieth Century Society

calls it a 'clever modern church'. It won a Civic Trust award in 1967.

As

a landmark, it is more visible now than when it was surrounded to the

west and south by other buildings which were levelled by the Blitz -

see these views [right] from the south-west: a 'retrospective' 1970s oil

painting by Noel Gibson and a 1960s photograph (and below for a plan which would have reversed this openness).

Du Prey comments, somewhat fancifully, that although

it always rose above its low-lying

surroundings like a tall white lily growing among weeds, its gleaming

Portland limestone now dominates the area as never before.

Less flatteringly, a journalist recently likened it to a

battered old boxer! And

the architectural critic Mervyn Blatch said ungraciously, in the 1970s,

we can again stare in

wonder or dismay at this strange building. Compare this with

the comments from Sir John Betjeman and Bishop Trevor Huddleston, in

the same period, here.

As

a landmark, it is more visible now than when it was surrounded to the

west and south by other buildings which were levelled by the Blitz -

see these views [right] from the south-west: a 'retrospective' 1970s oil

painting by Noel Gibson and a 1960s photograph (and below for a plan which would have reversed this openness).

Du Prey comments, somewhat fancifully, that although

it always rose above its low-lying

surroundings like a tall white lily growing among weeds, its gleaming

Portland limestone now dominates the area as never before.

Less flatteringly, a journalist recently likened it to a

battered old boxer! And

the architectural critic Mervyn Blatch said ungraciously, in the 1970s,

we can again stare in

wonder or dismay at this strange building. Compare this with

the comments from Sir John Betjeman and Bishop Trevor Huddleston, in

the same period, here.

In a Guardian column of 1 September 2003 Will Palin (now the Secretary of Save Britain's Heritage) wrote To

me, Nicholas Hawksmoor's St George-in-the-East is the most emotionally

powerful building in London ... It is the closest we have to the

pyramids of Egypt or the temples of Rome, with all the romance and

strangeness of a ruin ... Almost 300 years after landing in the fields

of Wapping, this architectural meteorite still dominates the landscape

- a reminder of its function as a symbol of the power of the

established church in the new East End of London.

Rectory

accommodation on two floors, and three flats, were created in the

former

gallery space, accessed by the spiral

staircases under each tower. With the old rectory variously tenanted,

the site (said one review of the time) became almost like a small

village - which was the then-Rector Alex Solomon's intention. In some

ways this consciously echoed Hawksmoor's notion of a 'primitive

Christian settlement' - some of his sketches for the site had shown

other buildings on each corner, to match the original parsonage house,

though these were never built.

Project 0001 of

the London

Docklands Development Corporation

was the cleaning of the church in 1982 - prompted, it is said, by a

visit to the area by Michael Heseltine who singled it out for

attention. The LDDC was set up by the Conservative

government to

regenerate the area by private/public partnerships. (One year it

sponsored a carol concert at St George-in-the-East, together with

Tobacco Dock Developments, featuring the Academy Chorus of St Martin in

the Fields.) Its 1987 publicity brochure grandly claimed Just

as the Renaissance heralded the modern world, culminating in an

outpouring of creative talent and new thought, so now, in its own, way,

a new freedom of expression in London Docklands is fashioning a wholly

new environment which heralds the 21st century. LDDC took credit for

creating 2.3m square metres of new floor space, the DLR, the Jubilee

Line extension, Canary Wharf, one of the tallest buildings in Europe,

30,000 new houses, the relocation of many companies into the area

and

an increase of jobs from 27,000 to 80,000 when it was dissolved in

1998. However, its legacy for local people remains open to question -

how many of the new jobs, for instance, were genuinely local? The

emphasis now is on social inclusion and neighbourhood

regeneration.

Project 0001 of

the London

Docklands Development Corporation

was the cleaning of the church in 1982 - prompted, it is said, by a

visit to the area by Michael Heseltine who singled it out for

attention. The LDDC was set up by the Conservative

government to

regenerate the area by private/public partnerships. (One year it

sponsored a carol concert at St George-in-the-East, together with

Tobacco Dock Developments, featuring the Academy Chorus of St Martin in

the Fields.) Its 1987 publicity brochure grandly claimed Just

as the Renaissance heralded the modern world, culminating in an

outpouring of creative talent and new thought, so now, in its own, way,

a new freedom of expression in London Docklands is fashioning a wholly

new environment which heralds the 21st century. LDDC took credit for

creating 2.3m square metres of new floor space, the DLR, the Jubilee

Line extension, Canary Wharf, one of the tallest buildings in Europe,

30,000 new houses, the relocation of many companies into the area

and

an increase of jobs from 27,000 to 80,000 when it was dissolved in

1998. However, its legacy for local people remains open to question -

how many of the new jobs, for instance, were genuinely local? The

emphasis now is on social inclusion and neighbourhood

regeneration.

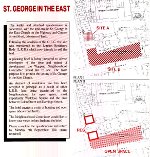

Following

the demise of the Greater London Council, the London Residuary Body

inherited ownership of the open sites to the south and west of the

church (along The Highway and Cannon Street Road), and in discussion

with them and with diocesan authorities Blashfield & Peto

(including local architect Mark Willingale) produced a plan in May 1987

for

're-enclosing' the church and gardens with a mixed development of

housing and offices to create a 'cathedral close-like' setting, which they proposed that the London Borough of Tower

Hamlets (LBTH) should develop [left -

originally buildings up to seven storeys were envisaged]; LRB

advertised the land for sale in 1988.

Following

the demise of the Greater London Council, the London Residuary Body

inherited ownership of the open sites to the south and west of the

church (along The Highway and Cannon Street Road), and in discussion

with them and with diocesan authorities Blashfield & Peto

(including local architect Mark Willingale) produced a plan in May 1987

for

're-enclosing' the church and gardens with a mixed development of

housing and offices to create a 'cathedral close-like' setting, which they proposed that the London Borough of Tower

Hamlets (LBTH) should develop [left -

originally buildings up to seven storeys were envisaged]; LRB

advertised the land for sale in 1988.

These proposals - though intended

to provide a co-ordinated approach of benefit all concerned - were

resisted, both locally and in the press [right is an article from The Observer of 27 May 1990]. LBTH later consulted on a compromise

scheme [far right] to

build housing either side of the main church entrance but leave the

southern aspect open. In the event, only the west side, in front of

the Rectory, was built on. 'Blashfield' and 'Peto' featured as

characters in the 1990 parish pantomime Georgilocks and the Three Developers. The remaining land has been incorporated into the Gardens scheme.

These proposals - though intended

to provide a co-ordinated approach of benefit all concerned - were

resisted, both locally and in the press [right is an article from The Observer of 27 May 1990]. LBTH later consulted on a compromise

scheme [far right] to

build housing either side of the main church entrance but leave the

southern aspect open. In the event, only the west side, in front of

the Rectory, was built on. 'Blashfield' and 'Peto' featured as

characters in the 1990 parish pantomime Georgilocks and the Three Developers. The remaining land has been incorporated into the Gardens scheme.

INSIDE THE CHURCH

Then...

Some

believe that a major inspiration for Hawksmoor's interior [left, as remodelled in the 19th century]

was Poplar Chapel [right],

one of only three surviving churches built in the Civil

War/Commonwealth period, initially by the East

India Company in 1653-4. It became the parish church of St Matthias and

was much altered, particularly in the mid-19th century by William

Milford Teulon (younger brother of the more famous architect Samuel

Sanders Teulon), and is now a community centre, but the roof details

and pillars (made from old ships' masts) can still be seen, and there are some clear similarities

with St George-in-the-East, the only one of Hawksmoor's churches to have a

vaulted ceiling. Here

is an informative illustrated leaflet about the Poplar building's

history.

Some

believe that a major inspiration for Hawksmoor's interior [left, as remodelled in the 19th century]

was Poplar Chapel [right],

one of only three surviving churches built in the Civil

War/Commonwealth period, initially by the East

India Company in 1653-4. It became the parish church of St Matthias and

was much altered, particularly in the mid-19th century by William

Milford Teulon (younger brother of the more famous architect Samuel

Sanders Teulon), and is now a community centre, but the roof details

and pillars (made from old ships' masts) can still be seen, and there are some clear similarities

with St George-in-the-East, the only one of Hawksmoor's churches to have a

vaulted ceiling. Here

is an informative illustrated leaflet about the Poplar building's

history. Its form is that of a vaulted Greek cross,

with flat-ceilinged corner rectangles supported by columns (a pattern

also found in Wren churches such as St Anne & St Agnes, and in the

Netherlands). The

woodwork, in Dutch or Austrian oak, was heavy and dark, and probably

not by Hawksmoor himself or of the same quality as

in his other churches, though the swag over the internal doorway

[see 1941 photo] was fine, and the pulpit was described as an exquisite

piece of carving and marquetry. Following repairs in 1783, a painting

of Christ in the Garden by

Clarkson was installed over the altar, paid for by subscriptions from

the 'principal inhabitants' - it seems to have been an indifferent work

- some merit in the drawing, but more in the colouring according to a contemporary critic, and according to Hadden in 1880 had been badly cleaned and patched up over the years, and was awaiting proper restoration.

In 1828, a century after its consecration, the antiquary John Britton and the architect Augustus Pugin published this

withering description of the church (with architectural plates).

Hawksmoor was completely out of fashion, and Pugin was of course a

prime advocate of the 'purity' of Gothic architecture. Its massing,

they said, was more suitable for workhouses and prisons; the exterior

was grotesque, and the interior heavy and gloomy. Fortunately, they

say, Hawksmoor's imitation of the worst features of Vanburgh (slated by

Walpole) never acquired much favour

with the public, nor is there any reason to apprehend it will ever

regain even the short-lived estimation in which it was held when the

present edifice was erected. They allow that it had a certain picturesque effect, and the masonry is exceedingly good.

(Although they describe the present configuration of the steps at the

west end, the plates show the pre-1800 arrangement, of steps within the

rotunda.)

In 1828, a century after its consecration, the antiquary John Britton and the architect Augustus Pugin published this

withering description of the church (with architectural plates).

Hawksmoor was completely out of fashion, and Pugin was of course a

prime advocate of the 'purity' of Gothic architecture. Its massing,

they said, was more suitable for workhouses and prisons; the exterior

was grotesque, and the interior heavy and gloomy. Fortunately, they

say, Hawksmoor's imitation of the worst features of Vanburgh (slated by

Walpole) never acquired much favour

with the public, nor is there any reason to apprehend it will ever

regain even the short-lived estimation in which it was held when the

present edifice was erected. They allow that it had a certain picturesque effect, and the masonry is exceedingly good.

(Although they describe the present configuration of the steps at the

west end, the plates show the pre-1800 arrangement, of steps within the

rotunda.)

In 1820 a new vault had been created and the churchyard drained, and a Vestry minute decreed that the five windows in the apse should be painted in enamel colours agreeably to the design and proposal of Mr. Collins, and that he be employed for that purpose, and paid the sum of five hundred guineas for the same. In 1829 the church was re-roofed, at a cost of £8,000, for which a building grant was obtained. During the work, a licence was granted for services to be held in the Schoolroom of St George's National School in Charles Street, Wapping. The parish population at the time was given as 32,528.

In 1839 a

stained

glass window of Faith, Hope and

Charity, from designs by Sir Joshua

Reynolds (copying New College, Oxford) was added to earlier windows in the apse - very indifferently-painted, according to the Illustrated London News on 3 March 1860, which includes an illustration [right] and critical comments on Bryan King's Lenten decoration of the sanctuary at the time of the Ritualism Riots.

In 1839 a

stained

glass window of Faith, Hope and

Charity, from designs by Sir Joshua

Reynolds (copying New College, Oxford) was added to earlier windows in the apse - very indifferently-painted, according to the Illustrated London News on 3 March 1860, which includes an illustration [right] and critical comments on Bryan King's Lenten decoration of the sanctuary at the time of the Ritualism Riots.

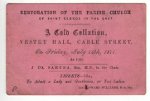

Here is

a ticket for a 'cold collation' to celebrate a futher restoration in

1871, which

removed the box pews and created additional seating, shown in this plan

between 1868-78 by Andrew Wilson, brother of churchwarden Joshua Wilson for 'reseating, repairs, general

restoration' (ICBS 07148: the Incorporated Church Building Society was

founded in 1818 to provide funds to build and enlarge churches; in 1982

its administration was transferred to the Historic Churches

Preservation Trust, and its archive is now at Lambeth Palace Library).

Here is

a ticket for a 'cold collation' to celebrate a futher restoration in

1871, which

removed the box pews and created additional seating, shown in this plan

between 1868-78 by Andrew Wilson, brother of churchwarden Joshua Wilson for 'reseating, repairs, general

restoration' (ICBS 07148: the Incorporated Church Building Society was

founded in 1818 to provide funds to build and enlarge churches; in 1982

its administration was transferred to the Historic Churches

Preservation Trust, and its archive is now at Lambeth Palace Library).

In 1880 Venetian

glass mosaics

were installed in the apse,

depicting five passion and resurrection

scenes: from left to right,

(1) the Baptism of Christ, (2) the Agony in the

Garden [two details], (3) the Crucifixion, (4) the Empty Tomb and (5) the meeting

with Mary

Magdalene in the Garden. The three central ones were given in

memory of

John and Phoebe Knight by their three sons; the one on the left was given by T.M.

Fairclough in memory of his uncle John Benton, who died in 1841 (both of them former churchwardens); and

the one on the right by Richard Foster to commemorate his parents'

marriage in 1805. John Knight had been one

of Bryan King's staunchest supporters thirty years earlier at the time of the Ritualism Riots. In 1879

King wrote, from Avebury, Well!

'Time and I against any two!' If I had proposed in my time to

have inserted a simple cross in place of the proposed crucifix, I

should have been burnt alive. [See above on his controversial Lenten hanging of a plain cross.] But seriously I do most heartily

congratulate you and your brothers on this result. Your father and

mother will now be the means, through their children, of preaching more

effectually than by any words to generations and generations of poor

souls the priceless truth of Jesus Christ and Him crucified! In

one generation the culture had changed, and the 'innovations' that

provoked the rioting no longer excited comment.The mosaics were saved in the Blitz and restored. [Pictures by kind permission of Matthew Andrews]

In 1880 Venetian

glass mosaics

were installed in the apse,

depicting five passion and resurrection

scenes: from left to right,

(1) the Baptism of Christ, (2) the Agony in the

Garden [two details], (3) the Crucifixion, (4) the Empty Tomb and (5) the meeting

with Mary

Magdalene in the Garden. The three central ones were given in

memory of

John and Phoebe Knight by their three sons; the one on the left was given by T.M.

Fairclough in memory of his uncle John Benton, who died in 1841 (both of them former churchwardens); and

the one on the right by Richard Foster to commemorate his parents'

marriage in 1805. John Knight had been one

of Bryan King's staunchest supporters thirty years earlier at the time of the Ritualism Riots. In 1879

King wrote, from Avebury, Well!

'Time and I against any two!' If I had proposed in my time to

have inserted a simple cross in place of the proposed crucifix, I

should have been burnt alive. [See above on his controversial Lenten hanging of a plain cross.] But seriously I do most heartily

congratulate you and your brothers on this result. Your father and

mother will now be the means, through their children, of preaching more

effectually than by any words to generations and generations of poor

souls the priceless truth of Jesus Christ and Him crucified! In

one generation the culture had changed, and the 'innovations' that

provoked the rioting no longer excited comment.The mosaics were saved in the Blitz and restored. [Pictures by kind permission of Matthew Andrews]

Robert Bridge's 1733 organ (25 speaking

stops on three manuals, on the west gallery of the church), proved to

be a problematic instrument. According to R.H. Hadden's 1880 East End Chronicle, in 1783 money had been spent to put it into a proper state of repair, and further sums in the 1820s. He says that in his day, the organ ... had for years been silent, for it had been rendered useless during the violent times [sc. of the Ritualism riots - but what actually happened to it?] - and Harry Jones, writing five years earlier in East and West London, said the same: the organ, the relics of which are concealed by an imposing case in the west

gallery, is pronounced to be hopelessly beyond repair. We do not use

it, but lead the choir with a small instrument which is placed in the

chancel, and which we are obliged to hire. But

it was agreed to restore the organ, at a cost of £1,000, to mark the

150th anniversary of the church (and proceeds from the sale of Hadden's

book went to the organ fund); the organ was rebuilt between 1881-86 by Gray and Davison. Other

renovations to the church interior took place

in 1886, paid for by the Rector C.H. Turner in memory of his

uncle

Henry Charleswood. The altar

was enlarged in 1905. Right are two late-Victorian photographs of the chancel.

Robert Bridge's 1733 organ (25 speaking

stops on three manuals, on the west gallery of the church), proved to

be a problematic instrument. According to R.H. Hadden's 1880 East End Chronicle, in 1783 money had been spent to put it into a proper state of repair, and further sums in the 1820s. He says that in his day, the organ ... had for years been silent, for it had been rendered useless during the violent times [sc. of the Ritualism riots - but what actually happened to it?] - and Harry Jones, writing five years earlier in East and West London, said the same: the organ, the relics of which are concealed by an imposing case in the west

gallery, is pronounced to be hopelessly beyond repair. We do not use

it, but lead the choir with a small instrument which is placed in the

chancel, and which we are obliged to hire. But

it was agreed to restore the organ, at a cost of £1,000, to mark the

150th anniversary of the church (and proceeds from the sale of Hadden's

book went to the organ fund); the organ was rebuilt between 1881-86 by Gray and Davison. Other

renovations to the church interior took place

in 1886, paid for by the Rector C.H. Turner in memory of his

uncle

Henry Charleswood. The altar

was enlarged in 1905. Right are two late-Victorian photographs of the chancel.

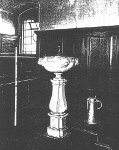

Left are some 1941 photographs

by Bedford Lemere & Co for the National Monuments Record (they were

leading architectural photographers

from their founding in 1860 until after the Second World War), showing

details of the interior just a few days before the Blitz - presumably

thay had been tasked with recording churches felt to be at risk. From

left to

right: the ceiling, the pulpit,

the porch, the warden's pew, the 'panelled room', the organ, and [poor-quality version] the font.

Left are some 1941 photographs

by Bedford Lemere & Co for the National Monuments Record (they were

leading architectural photographers

from their founding in 1860 until after the Second World War), showing

details of the interior just a few days before the Blitz - presumably

thay had been tasked with recording churches felt to be at risk. From

left to

right: the ceiling, the pulpit,

the porch, the warden's pew, the 'panelled room', the organ, and [poor-quality version] the font.

...and now

As explained

above, all

that now remains of that interior

is the apse, redecorated to the

original designs; the two stone corbels, on either side of the east

wall; and the mosaics,

rescued

from the ruins and restored.

As explained

above, all

that now remains of that interior

is the apse, redecorated to the

original designs; the two stone corbels, on either side of the east

wall; and the mosaics,

rescued

from the ruins and restored.

Until a few years ago the walls were painted

in a

stone colour, and the lampshades were black metal cylinders with small

vertical slits, in post-Festival of Britain style [right].

The font

[left] is said to have been brought

from the City church of St Benet, Gracechurch in the time of Rector Harry Jones, though a letter of 1929 to Rector Beresford [right] suggests that at that time at least there was some uncertainty about its provenance. (This Wren church was demolished in 1876 for

a road-widening scheme - second right just prior to demolition; its pulpit, allegedly by Grinling Gibbons, went

to St Olave Hart Street. St Benet's was joined to St Dionis Backchurch;

when this in turn was demolished, some of its furnishings went to the

new church of St Dionis Parson's Green; today this part of the City

makes up a group of parishes including St Mary Woolnoth, one of the

other six Hawksmoor churches.) This second font (its bowl recarved at

some point) stood in the north

aisle near the pulpit, the original font remaining in the

north-west baptistery [now the 'panelled room'], on account of

the great number of baptisms here according to Alfred Ernest Daniell London Riverside

Churches (Constable

1897 - he also wrote a physics textbook). The 'new' font was

first used here on 17 June 1877, with the Revd Sidney Vatcher

officiating. There is no suggestion

that the two fonts were used simultaneously; rather, a font in the main

church avoided baptism 'by relays' in the separate room, so the

original font probably fell out of use. See here for an account of how baptisms were handled earlier in the 19th century, and here for statistics and further comment.

The font

[left] is said to have been brought

from the City church of St Benet, Gracechurch in the time of Rector Harry Jones, though a letter of 1929 to Rector Beresford [right] suggests that at that time at least there was some uncertainty about its provenance. (This Wren church was demolished in 1876 for

a road-widening scheme - second right just prior to demolition; its pulpit, allegedly by Grinling Gibbons, went

to St Olave Hart Street. St Benet's was joined to St Dionis Backchurch;

when this in turn was demolished, some of its furnishings went to the

new church of St Dionis Parson's Green; today this part of the City

makes up a group of parishes including St Mary Woolnoth, one of the

other six Hawksmoor churches.) This second font (its bowl recarved at

some point) stood in the north

aisle near the pulpit, the original font remaining in the

north-west baptistery [now the 'panelled room'], on account of

the great number of baptisms here according to Alfred Ernest Daniell London Riverside

Churches (Constable

1897 - he also wrote a physics textbook). The 'new' font was

first used here on 17 June 1877, with the Revd Sidney Vatcher

officiating. There is no suggestion

that the two fonts were used simultaneously; rather, a font in the main

church avoided baptism 'by relays' in the separate room, so the

original font probably fell out of use. See here for an account of how baptisms were handled earlier in the 19th century, and here for statistics and further comment.

By the font

stands a paschal candlestick [left, plus detail] carved by Father Groser's son Michael (biography here), with seven roundels depicting passion and resurrection

symbols. Over the font hangs an unusual metal corona [right],

in aluminium and copper plumbing materials, designed in 1966 by Frank

Berry and made by Arthur Greenwood of the Brotherhood of Prayer and

Action who were working in the parish at that time. It holds twelve

candles, which are lit at Christmas and other festivals.

By the font

stands a paschal candlestick [left, plus detail] carved by Father Groser's son Michael (biography here), with seven roundels depicting passion and resurrection

symbols. Over the font hangs an unusual metal corona [right],

in aluminium and copper plumbing materials, designed in 1966 by Frank

Berry and made by Arthur Greenwood of the Brotherhood of Prayer and

Action who were working in the parish at that time. It holds twelve

candles, which are lit at Christmas and other festivals.

In

the south-east corner is a small plaque

[left] commemorating Fr Alex

Solomon, Rector 1958-79, who inspired and led the rebuilding.

On St George's Day 1991, a week after the 50th anniversary of the

destruction of the church interior, his widow Nora presented a lavabo bowl

(used by the priest for the ritual rinsing of his hands before the

eucharistic prayer) [right] designed

for the church and made by Tom Tudor-Pole,

whose workshop was in Spitalfields. It bears the inscription I will wash my hands in innocency, Oh [sic] Lord, and so will I go to thine altar (Ps

26.6) and on the inside Remember

Alexander Solomon, Priest around

the martyr cross of St George-in-the-East, based on four Roman swords -

as on the plaque.

Pierced wave forms are added around the lips of the bowl. It is unusual

- but very appropriate - to have such a commissioned piece, of which he

would surely have approved.

In

the south-east corner is a small plaque

[left] commemorating Fr Alex

Solomon, Rector 1958-79, who inspired and led the rebuilding.

On St George's Day 1991, a week after the 50th anniversary of the

destruction of the church interior, his widow Nora presented a lavabo bowl

(used by the priest for the ritual rinsing of his hands before the

eucharistic prayer) [right] designed

for the church and made by Tom Tudor-Pole,

whose workshop was in Spitalfields. It bears the inscription I will wash my hands in innocency, Oh [sic] Lord, and so will I go to thine altar (Ps

26.6) and on the inside Remember

Alexander Solomon, Priest around

the martyr cross of St George-in-the-East, based on four Roman swords -

as on the plaque.

Pierced wave forms are added around the lips of the bowl. It is unusual

- but very appropriate - to have such a commissioned piece, of which he

would surely have approved.

On

one of the pillars on the south side [right] is a little

abstract watercolour

by

Peter Bedford, who as a member of the Pacifist Service Units was on

fire watch at

the top of the tower the

night the bomb fell. He became an architect, and took up painting as a

retirement hobby. It was only when he and his wife visited the church

in 1997 that he realised, in conversation with the Rector, that the

Blitz had provided the subconscious inspiration for a series of

abstract paintings he had recently completed, of which this is one. It

bears the inscription How beautiful

upon the mountains are the feet of him that bringeth good tidings of

peace (Isaiah 52.7) and Remember

before God the horror and destruction of war / Pray and work for peace

and reconciliation in our world, together with a memorial

plaque to the artist who died in 1998.

On

one of the pillars on the south side [right] is a little

abstract watercolour

by

Peter Bedford, who as a member of the Pacifist Service Units was on

fire watch at

the top of the tower the

night the bomb fell. He became an architect, and took up painting as a

retirement hobby. It was only when he and his wife visited the church

in 1997 that he realised, in conversation with the Rector, that the

Blitz had provided the subconscious inspiration for a series of

abstract paintings he had recently completed, of which this is one. It

bears the inscription How beautiful

upon the mountains are the feet of him that bringeth good tidings of

peace (Isaiah 52.7) and Remember

before God the horror and destruction of war / Pray and work for peace

and reconciliation in our world, together with a memorial

plaque to the artist who died in 1998.

![]()

Opposite, on the north

side [left],

is an icon of Christ the Merciful written by Dom

Anselm Shobrook OSB, commissioned in 1997, with the text Come to me, you who labour and

are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.

Opposite, on the north

side [left],

is an icon of Christ the Merciful written by Dom

Anselm Shobrook OSB, commissioned in 1997, with the text Come to me, you who labour and

are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.

On the north wall is the organ, an

extension instrument of 1964 by N.P.

Mander.

(The original

instrument of 1733, of 25 speaking stops on three manuals by Robert

Bridge, had been rebuilt between 1881-86 by

Gray and Davison, but nothing of this instrument survived the Blitz.)

It is accessed for tuning and maintenance via one of the flats. Far right is the temporary instrument that preceded it.

The silver altar candlesticks and processional cross and wooden alms plate were designed for the church. Like the lavabo bowl and memorial plaque mentioned above, the cross and alms plate have the martyr cross motif.

The communion

silver

is a mixture of 20th century pieces and items from former churches in

the parish: the silver gilt set from Christ Church Watney Street

used at festivals, and items from St Paul Dock Street. None of the

historic plate of the parish church survives. Two George II flagons,

and a pair of 18th century patens and chalices, together with some

Stafford plate used at St Matthew Pell Street, were sold in the

1920s, via an

anonymous donor, for display in the London Museum. See this

faculty correspondence, which shows how disposing of the 'family silver' was

dealt with in those days. More recently, a 1930s chalice and paten, and

a boxed communion set (originally for use on a ship?) were given

to the Diocese of Namibia in 1994, and at the suggestion of the Bishop

of London, a Victorian chalice and paten to the Diocese of

Nigeria-Bauchi in 1998.

The sacrament is

reserved (for taking holy communion to the sick and housebound) in a

hanging pyx

in the apse, behind the altar, installed in 1969 in memory of Charles

Turner (Bishop of Islington). It is covered

with a white veil and marked with a permanent white (energy-efficient!)

light - deliberately brighter than is traditionally used, to provide a

visible sign at night from The Highway and Gardens of Christ's presence

in his church. Hanging pyxes were in vogue at

that time; ours is manually rather than electrically raised and lowered

- unlike those in smarter West End churches. (Harry Williams CR

recalled in his autobiography his first vicar's remark in this church even the good Lord travels

in

a lift.)

The sacrament is

reserved (for taking holy communion to the sick and housebound) in a

hanging pyx

in the apse, behind the altar, installed in 1969 in memory of Charles

Turner (Bishop of Islington). It is covered

with a white veil and marked with a permanent white (energy-efficient!)

light - deliberately brighter than is traditionally used, to provide a

visible sign at night from The Highway and Gardens of Christ's presence

in his church. Hanging pyxes were in vogue at

that time; ours is manually rather than electrically raised and lowered

- unlike those in smarter West End churches. (Harry Williams CR

recalled in his autobiography his first vicar's remark in this church even the good Lord travels

in

a lift.)

At the doors, and on the bishop's chair (1969, given in memory of Albert Barratt, vandalised a few years ago but now restored - Arthur Bailey's drawing of the side panel, 1967, right) are fibreglass copies of a bronze original of St George and the dragon [right].

THE TOWER

In

the rebuilding, the tower was stablised (note the fire damage marks,

and the concrete cross on which the flagpole sits - it can be lowered

down for painting). The flagpole was renewed in 2003 with a safety

ladder and harness added, and topped by a crown to mark the Queen's

golden jubilee.

In

the rebuilding, the tower was stablised (note the fire damage marks,

and the concrete cross on which the flagpole sits - it can be lowered

down for painting). The flagpole was renewed in 2003 with a safety

ladder and harness added, and topped by a crown to mark the Queen's

golden jubilee.

See here for details

and pictures of the bells: a light ring of

eight, cast in 1965 as a demonstration ring for bomb-damaged

churches by the Whitechapel

Foundry

- an ancient, famous and very local firm. They had also restored the

old bells in 1938 in memory of Charles John Beresford (Rector

1925-36), which were destroyed in the Blitz. There had been a clock,

installed in the 1820s at a cost of £400, but it was not replaced.

Above the bells is a room [right],

the original purpose of which is unclear (apart from its windows

serving an architectural function). It is too high up the tower to

be accessed by any but the most energetic!

Above the bells is a room [right],

the original purpose of which is unclear (apart from its windows

serving an architectural function). It is too high up the tower to

be accessed by any but the most energetic!

As elsewhere, the

choir traditionally sang from the tower on Ascension Day or May morning

- this was mentioned in a 2012 psycho-geographical tour round some of

the Hawksmoor churches on Radio 4.

Then...

The

crypt, originally accessed from the south-west corner of the church,

had been extensively used for burials, in a series of separate vaults.

Daniel Lysons, in The Environs of London, vol 2: County of Middlesex

(1795) records the following memorial tablets in the crypt: William

Norman (1729); Thomas Trott (1733); John Dagge (1735); Joseph Crowcher

(1752 - one of the original churchwardens); John Bristow (1762); and

Samuel Holman (1793).

After

the Blitz, from 1942 the crypt was used as an air raid shelter, though

space was limited: corridors went round the perimeter, leading into

separate chambers where coffins were stacked on shelves. In the coming

years, occasional crypt tours were organised, which young people

remember as a scary experience.

As

explained on the rebuilding

page, the decision was made

to clear and remodel the crypt. Between 11 October and 9 November 1960,

686 boxes and lead coffins, from 59 vaults, were

removed and reburied at Brookwood Cemetery

- click left for the detailed record. The crypt then became a

hall, with a large

stage, which for some years was widely used as rehearsal and

performance space both by professional companies, in line with the

Rector's aspirations (see here for his retrospective account), and for

some big pop music events, as well as for parish functions - here

are more details of all of these). See here

for a more unusual use of the crypt in 1976, to provide overnight

accommodation for a group of Angola-bound mercenaries who had persuaded

the Rector they were a film crew...

As

explained on the rebuilding

page, the decision was made

to clear and remodel the crypt. Between 11 October and 9 November 1960,

686 boxes and lead coffins, from 59 vaults, were

removed and reburied at Brookwood Cemetery

- click left for the detailed record. The crypt then became a

hall, with a large

stage, which for some years was widely used as rehearsal and

performance space both by professional companies, in line with the

Rector's aspirations (see here for his retrospective account), and for

some big pop music events, as well as for parish functions - here

are more details of all of these). See here

for a more unusual use of the crypt in 1976, to provide overnight

accommodation for a group of Angola-bound mercenaries who had persuaded

the Rector they were a film crew...

...and now

Use of the hall, by outside groups and the parish, declined, and it needed considerable maintenance. As explained here, in 2005 it was decided by the diocese of London - without much reference to the parish, then in vacancy - to convert the eastern (stage) end into an administrative base for the North Thames Ministerial Training Course, as part of the Bishop of London's vision of a 'Christian university' along The Highway. They remained here until 2012, and for the following academic year the space was temporarily occupied by Wapping High School pending the provision of more permanent accommodation. In 2006 the parish adapted the rest of the crypt as a nursery school (financed by the sale to the diocese of Church House, Wellclose Square), and it now houses Green Gables Montessori Nursery School.CHURCHYARD & GARDENS ~ RECTORY

On the north of the church lies the enclosed area once known as the 'Churchwardens' Garden' which has been landscaped as a play area for the children of the nursery school. It is entered through the Bryan King gate, which was re-created in 2008. It is through this space, at the time of the Ritualism Riots of 1859-60, that the Rector escaped from the mob in church, back to the Rectory, whose front door still has metal reinforcements and an iron bar (gate and door shown here). It is the original parsonage house; full details of its history, and recent restoration, are shown here.

To the

east of

the church lies St

George's Gardens,

comprising the former churchyard and various other plots of land. Some

of the old headstones are now relocated against the walls [right].

The original area, consecrated in 1729, was extended on the north

exactly a century later. Here is a

description of an 1824 funeral procession to a family vault near the

west door.

To the

east of

the church lies St

George's Gardens,

comprising the former churchyard and various other plots of land. Some

of the old headstones are now relocated against the walls [right].

The original area, consecrated in 1729, was extended on the north

exactly a century later. Here is a

description of an 1824 funeral procession to a family vault near the

west door.

Among the significant tombs and monuments in the churchyard, as recorded by Daniel Lysons in 1795, were

| Thomas Evans, merchant (1730); Capt. John Hammerton (1732); Mr. Henry Raine (1738); Capt. Henry Allen (1740); Mr. William Thompson, surgeon (1742); Capt.John Basnett (1744); Olive, wife of Lach Machlachlan, Esq. of Amwell-Bury (1751); John Mewse, surgeon (1752); Robert Sax, Esq. (1759); Mr. Joseph Ames (1759); Capt. Henry Nell (1760); Capt. David Crichton (1761); Capt. Anthony Buskin (1764); Capt. Samuel Newman (1764); Hugh Roberts, Esq. (1771); Capt. Robert Oliver (1772); Capt. Thomas Evans of the Royal Navy (1775); Capt. George Dobill (1776); Capt. John Bonner (1778); Robert Sax, Esq. (1779); Capt. Charles Robinson (1781); Capt. Andrew Glassby (1782); Mrs. Elizabeth Woolsey (1782); James Watson, Lieutenant in the Navy (1783); Alexander Machlachlan, Esq. (1783); Capt. William Tweedall (1785); John Abbot, Gent. (1787); Joseph Lash, Lieutenant in the Navy (1787); William Duffin, Esq. (1793); and Capt. Thomas Randall (1793) |

One which he did not record was that of Richard Morris

(1702/3-79), one of four notable brothers born in Anglesey, who moved

to London in his teens and worked as a clerk in the navy office,

eventually becoming chief clerk of foreign accounts, from which, unable

to afford to retire, he was superannuated in the year of his death; he

died at the Tower and was buried here with the third of his four wives,

and children. A folklorist and scholar of the Welsh language, he is

chiefly remembered for supervising translations of of the Bible in 1746

and 1752 (published by SPCK), and the Book of Common Prayer, and was first president of the Cymmrodorion Society in 1751. A full biography (in Welsh) by the Revd Dr Dafydd Wyn Wiliam, Cofiant Richard Morris, was published in 1999,

Others were added prior to the closure of the churchyard.

Right is the table of fees, as printed in John Caugh's 1840 Funeral Guide (they are comparable with those of other parishes; see here for an example of a private burial ground charging lower rates). Like other urban churchyards, it became,

in the words of Mrs Basil

Holmes in London Burial Grounds (1896/7),

a gorged London graveyard ... [to which] the close courts and

poverty-stricken streets of the parish sent every year many hundred

tenants. (See here

for more about 'Bella' Holmes and her work: her husband was the

secretary of the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association.) Burials

ceased after a series of Acts of Parliament, culminating in the 1852

Metropolitan Burial Act,

which closed churchyards and promoted the rise of public, out-of-town

cemeteries; Bryan King conducted the last regular interments here

(eight in number) on 1 October 1854. The churchyard was then closed to

public access for the

next twenty years. (See this 1855 Charge by the Archdeacon of London to his clergy, Intramural Burial in England Not Injurious to the Public Health: its Abolition Injurious to Religion and Morals, protesting against government high-handedness in addressing the problem.) In

April 1859 the Privy Council, making directions for various churches,

ordered that within the church at St George's the accessible public

vaults should be freely limewashed, coffins in the public vault

covered in earth and concrete, under the direction of the Medical

Officer of Health, and that McDougall's

powder, chlorine or other disinfectant be used wherever required. After

the closure, five further interments took place, by licence from the

Home Secretary - details here.

Right is the table of fees, as printed in John Caugh's 1840 Funeral Guide (they are comparable with those of other parishes; see here for an example of a private burial ground charging lower rates). Like other urban churchyards, it became,

in the words of Mrs Basil

Holmes in London Burial Grounds (1896/7),

a gorged London graveyard ... [to which] the close courts and

poverty-stricken streets of the parish sent every year many hundred

tenants. (See here

for more about 'Bella' Holmes and her work: her husband was the

secretary of the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association.) Burials

ceased after a series of Acts of Parliament, culminating in the 1852

Metropolitan Burial Act,

which closed churchyards and promoted the rise of public, out-of-town

cemeteries; Bryan King conducted the last regular interments here

(eight in number) on 1 October 1854. The churchyard was then closed to

public access for the

next twenty years. (See this 1855 Charge by the Archdeacon of London to his clergy, Intramural Burial in England Not Injurious to the Public Health: its Abolition Injurious to Religion and Morals, protesting against government high-handedness in addressing the problem.) In

April 1859 the Privy Council, making directions for various churches,

ordered that within the church at St George's the accessible public

vaults should be freely limewashed, coffins in the public vault

covered in earth and concrete, under the direction of the Medical

Officer of Health, and that McDougall's

powder, chlorine or other disinfectant be used wherever required. After

the closure, five further interments took place, by licence from the

Home Secretary - details here.

It

then became effectively the first London churchyard to

become a public park in the care of the local authority (two others had

been partially cleared), opened

in

January 1877 [left is

the invitation ticket]. Harry Jones, the Rector, was very determined in

pursuing his vision for an oasis of green space in the crowded city -

the nearest park was Victoria Park, over two miles away - and a

memorial in favour of the proposals was signed by 650 local

residents. It was a cumbersome process, involving

widespread consultation, and transfer by the parish Vestry from itself

as an ecclesiastical body to itself as the local goverment body! Four years

later the Metropolitan

Open Spaces Act 1881 (extending a more limited Act of 1877)

simplified the process. The necessary legal

judgement is reported in Re

Rector &c of St George-in-the-East (1876) 1 PD 311, which made reference to a London consistory court judgement of 1836.

(Until then the use of consecrated ground for secular purposes required

a private Act of Parliament, but to save expense, for the convenience

of the public, church courts began to grant faculties for footpaths and

gates in the specific case of former burial grounds in densely

populated areas, and this was one of the first such instances. A 1900

case - on street widening in Bideford - held that this exception

applied wherever the purpose for which the ground was originally consecrated can no longer lawfully be carried out, but as one commentator commented tartly, this disregarded parishioners' rights to be returned to the parent earth for dissolution.) Here is Harry Jones' own vision of the scheme - written in 1875 before it came to fruition - and here

are press reports from 1876 and 1901 (after Harry Jones' death), plus a

letter from the diocesan Chancellor of 1907 (a few years after

responsibility was transferred to the newly-formed Stepney Borough

Council) confirming

that in his opinion this was a 'first'.

It

then became effectively the first London churchyard to

become a public park in the care of the local authority (two others had

been partially cleared), opened

in

January 1877 [left is

the invitation ticket]. Harry Jones, the Rector, was very determined in

pursuing his vision for an oasis of green space in the crowded city -

the nearest park was Victoria Park, over two miles away - and a

memorial in favour of the proposals was signed by 650 local

residents. It was a cumbersome process, involving

widespread consultation, and transfer by the parish Vestry from itself

as an ecclesiastical body to itself as the local goverment body! Four years

later the Metropolitan

Open Spaces Act 1881 (extending a more limited Act of 1877)

simplified the process. The necessary legal

judgement is reported in Re

Rector &c of St George-in-the-East (1876) 1 PD 311, which made reference to a London consistory court judgement of 1836.

(Until then the use of consecrated ground for secular purposes required

a private Act of Parliament, but to save expense, for the convenience

of the public, church courts began to grant faculties for footpaths and

gates in the specific case of former burial grounds in densely

populated areas, and this was one of the first such instances. A 1900

case - on street widening in Bideford - held that this exception

applied wherever the purpose for which the ground was originally consecrated can no longer lawfully be carried out, but as one commentator commented tartly, this disregarded parishioners' rights to be returned to the parent earth for dissolution.) Here is Harry Jones' own vision of the scheme - written in 1875 before it came to fruition - and here

are press reports from 1876 and 1901 (after Harry Jones' death), plus a

letter from the diocesan Chancellor of 1907 (a few years after

responsibility was transferred to the newly-formed Stepney Borough

Council) confirming

that in his opinion this was a 'first'.

The east end of

the

churchyard, and the whole of the Wesleyan Chapel

burial

ground behind

the Town Hall (which the Vestry purchased in 1876), formed

the original garden. Many of the headstones were relocated around the

perimeter (unfortunately those moved or discarded were not recorded, as

is standard practice nowadays - though the Bancroft Library

holds a set of rubbings made during the 2007/8 refurbishment [see

below]). New avenues of trees were planted - 'Rector's Walk' and 'Lime

Avenue'. (Harry Jones says that a small avenue of lime trees, known as

'Rector's Walk', had previously existed - I suppose from having been

the pacing-ground of some predecessor of mine - but the high walls made it completely inaccessible to others.)

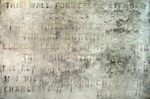

At this time, they also built a mortuary chapel, perhaps

replacing one on the Wesleyan site - more details here. In the north-east corner, by what is now a

children's playground, a tablet set into the wall records This

wall formerly extended 190 feet westwards from this stone and then

turned northwards eleven feet to junction with the churchyard wall, with the names of the Rector and churchwardens M.J. Hickman and Charles Cox and the date November 1876 [left]. On this wall is also an undated drinking fountain [right], Erected

by the Metropolitan Drinking Fountain and Cattle Trough

Association. The remainder of the churchyard

was cleared in

1886, and the whole was put in order

and laid out at the sole expense of Augustus George Crowder JP. Mrs Holmes described

it as always

bright and neat and full of people enjoying the seats, the grass, the

flowers and the air, and noted that the project was unique in being an amalgamation

of a churchyard and a dissenting burial ground.

At this time, they also built a mortuary chapel, perhaps

replacing one on the Wesleyan site - more details here. In the north-east corner, by what is now a

children's playground, a tablet set into the wall records This

wall formerly extended 190 feet westwards from this stone and then

turned northwards eleven feet to junction with the churchyard wall, with the names of the Rector and churchwardens M.J. Hickman and Charles Cox and the date November 1876 [left]. On this wall is also an undated drinking fountain [right], Erected

by the Metropolitan Drinking Fountain and Cattle Trough

Association. The remainder of the churchyard

was cleared in

1886, and the whole was put in order

and laid out at the sole expense of Augustus George Crowder JP. Mrs Holmes described

it as always

bright and neat and full of people enjoying the seats, the grass, the

flowers and the air, and noted that the project was unique in being an amalgamation

of a churchyard and a dissenting burial ground.

The Morning

Post of 2 August 1935 included a picture [left] with the caption

The Morning

Post of 2 August 1935 included a picture [left] with the caption

|

|

In

the 1980s land along The Highway was added to the Gardens, which were

re-landscaped by the London Docklands Development Corporation in 1996;

Library Place was incorporated in 2002. (The Passmore

Edwards Public Library was opened in 1898, adjacent to the

Town Hall, and destroyed in the Blitz in 1941 - see here). In 2008 the Gardens

re-opened after a restoration and conservation project, planned in

consultation with the church authorities and local people, funded by

the Heritage Lottery Fund to the tune of £1.2m with £420,000 from

Tower Hamlets and an additional grant of £100,000 from the London

Marathon Charitable Trust. It is good to see them being enjoyed once

more. Sadly,

the project did not include, as originally intended, the former mortuary

chapel which in 1902 had became a Nature Study Museum - this link explains our hopes

for its restoration. A map of current land ownership [right] shows the complex nature of the site.

In

the 1980s land along The Highway was added to the Gardens, which were

re-landscaped by the London Docklands Development Corporation in 1996;

Library Place was incorporated in 2002. (The Passmore

Edwards Public Library was opened in 1898, adjacent to the

Town Hall, and destroyed in the Blitz in 1941 - see here). In 2008 the Gardens

re-opened after a restoration and conservation project, planned in

consultation with the church authorities and local people, funded by

the Heritage Lottery Fund to the tune of £1.2m with £420,000 from

Tower Hamlets and an additional grant of £100,000 from the London

Marathon Charitable Trust. It is good to see them being enjoyed once

more. Sadly,

the project did not include, as originally intended, the former mortuary

chapel which in 1902 had became a Nature Study Museum - this link explains our hopes

for its restoration. A map of current land ownership [right] shows the complex nature of the site.

At

the east of the church is the War Memorial of 1924 [left] - see here for an

account of its planning and dedication, and a list of the names it

commemorates -

and

(now enclosed by

railings) the Raine

Memorial [right]

- more here about this memorial, and Henry

Raine's schools and his curious provision of a marriage

portion for local girls.

At

the east of the church is the War Memorial of 1924 [left] - see here for an

account of its planning and dedication, and a list of the names it

commemorates -

and

(now enclosed by

railings) the Raine

Memorial [right]

- more here about this memorial, and Henry

Raine's schools and his curious provision of a marriage

portion for local girls.

On

the wall of the town hall, at the north of the gardens, is a mural depicting

the Battle of Cable Street in 1936, the focus of 75th anniversary events in 2011.

NEIGHBOURING SITES - CONSERVATION AREA

The church and churchyard form the major part of St George-in-the-East Conservation Area - see here

for a map, and here for the text of the 2009 character appraisal and management guidelines (click on 'St

George-in-the-East' in both cases). The conservation area has since been extended to

include the Old Rose

pub across The Highway [left in the 1930s and 2010] which sadly closed in 2011. Right is the uncleared bomb-damaged site to the

south-east of the church, some time in the 1950s.

The church and churchyard form the major part of St George-in-the-East Conservation Area - see here

for a map, and here for the text of the 2009 character appraisal and management guidelines (click on 'St

George-in-the-East' in both cases). The conservation area has since been extended to

include the Old Rose

pub across The Highway [left in the 1930s and 2010] which sadly closed in 2011. Right is the uncleared bomb-damaged site to the

south-east of the church, some time in the 1950s.

Next to the church is St George's Pools, widely used by schools and local people [former interior left, rebuild right] was of its time, and it is not within the conservation area, but as the report rightly observes, it presents a dead frontage to the road -

though it was given a bit of a face-lift for the Olympics in 2012.Tower Hamlets

identified this as a site for possible development as part of its 2011

consultation on the local development framework.

Next to the church is St George's Pools, widely used by schools and local people [former interior left, rebuild right] was of its time, and it is not within the conservation area, but as the report rightly observes, it presents a dead frontage to the road -

though it was given a bit of a face-lift for the Olympics in 2012.Tower Hamlets

identified this as a site for possible development as part of its 2011

consultation on the local development framework.