Bryan Corcoran Ltd, Mark Lane & Backchurch Lane

His son Bryan joined him - the firm of Corcoran & Son was established in 1805. By 1823 they were at 36 Mark Lane, insured in 1830 as stationer, bookbinder and wire screen weaver, corn machine maker, and warehouseman - elsewhere paperhanger is added. In 1836 they paid poor rates on the premises as Bryan Corcoran & Co:

Philetas Richardson was a partner, but was excluded from the register

of voters because the rates were not paid in his name. The printing

work continued - see here

for a book they printed in 1864 (on the history of All Hallows

Berkyngechirche in the City, reflecting the family's ecclesiastical

interests) - but their primary trade was supplying millstones [left is

their mark on the runner stone (the one that moves in grinding) of Provender Mill, Brixton, under

restoration, and a tie plate from elsewhere] plus equipment for

millers and maltsters, including the manufacture of a range of measuring tools.

His son Bryan joined him - the firm of Corcoran & Son was established in 1805. By 1823 they were at 36 Mark Lane, insured in 1830 as stationer, bookbinder and wire screen weaver, corn machine maker, and warehouseman - elsewhere paperhanger is added. In 1836 they paid poor rates on the premises as Bryan Corcoran & Co:

Philetas Richardson was a partner, but was excluded from the register

of voters because the rates were not paid in his name. The printing

work continued - see here

for a book they printed in 1864 (on the history of All Hallows

Berkyngechirche in the City, reflecting the family's ecclesiastical

interests) - but their primary trade was supplying millstones [left is

their mark on the runner stone (the one that moves in grinding) of Provender Mill, Brixton, under

restoration, and a tie plate from elsewhere] plus equipment for

millers and maltsters, including the manufacture of a range of measuring tools.| The DUKE OF SOMERSET (in the Absence of the EARL OF HARROWBY) in the Chair Mr Bryan Corcoran Is called in; and examined as follows: What is your profession?—A Bushel maker, as well as a manufacturer of Mill stones for Millers. How do you ascertain the correctness of the Bushel which you make?—By the Standard at Guildhall in London; our Measures are prepared in the neatest and safest manner we can, sufficiently drawing out all the moisture; the sap is completely extracted, as we suppose, and it is almost immoveable. After what model is it made?—Round, with an even bottom, according to what it is; if it is for a Farmer, we make it Sixteen inches diameter and the depth is regulated accordingly to hold a bushel, about Twelve inches deep; if it is for a Corn Merchant, we generally go by the Standard, Eighteen inches and Half wide and Eight inches deep, which is as the Act of Parliament expresses it and is called a Meter bushel. When you have made a Bushel as accurately as you can by Measurement, how do you ascertain its contents?—No otherwise than by comparing it with the Standard at Guildhall, the same as when we take a copy of the Standard in the Exchequer for a Corporate Body, we endeavour to take it as accurately as we can from the copy which is in the Exchequer; but which is not correct by any means. Do you verify the accuracy of that Bushel which has been made by Measurement by trying what quantity of liquid it will contain?—Yes; if it contains equal to the other we do not go into the minutiae what the Quantity is, but we make it the same as the Standard at Guildhall or the Exchequer. You do not weigh the water?—No, never. There is one other Bushel we make for the Granary Keepers and the Wharfingers, and those who turn over so much grain in the port of London, which is Two inches deeper, but will hold the same in capacity; both correspond, or so nearly as to pass between Buyer and Seller; this narrow Bushel or Drum bushel is for the convenience of the workmen, that one man can turn over with agility and practice from sixty to seventy quarters in one hour, which cannot be done by the wide Bushel; that must be worked double-handed; but with the narrow Bushel one man can do it; that is for the Granary keepers in the port of London. Do you uniformly try the accuracy of your Bushel by filling it with water, and ascertaining the quantity of water it holds?—Always; from practice we know directly by our rule what the Bushel is, within perhaps the thickness of a sheet of paper or two; when these are prepared in the dry manner I have spoken of, we take them to the Guildhall of London; we always make them large enough, so that we can take down the superfluity, and that it may be finished afterwards; this is done before the iron is put on, before it is hooped; our wooden bushels are hooped with Iron: we always take care there shall be plenty of measure, then the Sealer whose business it is to seal them, the officer of the corporation, seals them with a brand, burnt on the inside and the opposite side; without that voucher we do not sell them. When you have made a Bushel as accurately as you can by Measurement, and come to try it by its contents in water, do you frequently find that it requires a good deal of correction?— Sometimes very little; the water swells it a little, but it comes very soon to, while we are finishing it. May not the measurement of a Bushel be made correctly without ascertaining its contents with water?—I cannot say; we never send it out without. When you go to try it at Guildhall do you fill the Guildhall bushel with water?—Yes, the Guildhall Bushel is filled with water, and in as careful a manner as we can we take it out; there are Three wedges like a tripod, so that we can regulate it with the greatest nicety; the water is taken out of the Guildhall measure and put into the other and back again; we then mark it on the inside with a point, and reduce it down to that point, to equal where the water was, and this same water is restored again into the Guildhall Standard; that is the practice with us. Is not there a penalty on your selling measures without their being stamped?—I have consulted the Act, but have not found that there was a penalty. The Mark is put near the top?—Yes, the Bushel cannot be reduced afterwards without infringing on the burnt seal. You have said that the Measure at the Exchequer is faulty, and different from the measure at Guildhall, have you not?—Yes, it is; the Act of Parliament refers to its being Eighteen inches and a half diameter and Eight inches deep; it is not so at the Exchequer, but goes tapering to the bottom, and has been cut out to enlarge it at some former time, and the lip of it is very unequal; some parts are up and some parts down; it is a very unequal measure, and very unfit to be called a Standard for any thing. Has that happened by wearing?—It never was good; I have sent off, perhaps, more copies to Corporate Bodies than any one; but I dare not say that they are accurately like one another. Are the copies sent from the pattern in Guildhall or the Exchequer Standards from the Exchequer?—Wooden ones from Guildhall. Do you know the difference between the two?—They are made as nearly as the human hand can make them; I believe in the time that Mr. Alderman Combe was Mayor of London, he took an active part in it, and there were pains taken to make them alike, because prior to this the Guildhall Standard, being correct and circular, held more; it was a better made Bushel, and held what it ought; but I believe at that time it was reduced a trifle merely to correspond with the Exchequer Standard. They are both Metal measures?—Yes, Brass. If you, as a Bushel maker, were to have assigned to you the task of making a Brass and perfect Measure, do you suppose that Measure could be deranged again?—Never, but by the greatest violence; those I have made have been, perhaps, at the lip, half an inch thick very nearly, and a corresponding thickness all round, and at the bottom, with cast handles to it complete; there is nothing can ever destroy the Standard if it is done properly. Do the Corporations frequently send up their copies to have them again verified?—No, there is no occasion; for a Standard which is once turned out properly can never vary; the principal thing we want is to have a proper Standard at the Exchequer, or wherever it may be directed; then there would be no difficulty: we suppose that the Exchequer is the place where the Standard should be that is identified as the Standard of England. The Measures made from the Exchequer Standard, you say, do not always coincide with each other?—No, it is so imperfect that they cannot be made to coincide. The Standards made after the Guildhall measure must all coincide?—There are none made from the Guildhall measure, only from the Exchequer; hence comes the inequality. If there were a new one, its being made smaller at the top than at the bottom, would give us a facility in ascertaining the precise quantity. The Witness is directed to withdraw. |

As a result of the 1824 Act, they were one of several firms making chrondrometers, or corn balances. This determined weight per bushel from a sample from which impurities had been removed.

As a result of the 1824 Act, they were one of several firms making chrondrometers, or corn balances. This determined weight per bushel from a sample from which impurities had been removed.

Another product was a grain tester scale [left], used

to work out the percentage weight of a sack of grain (in pounds per

bushel) after the grain husk, dust and dirt is removed, enabling the

true value of the sack to be calculated - the difference could be quite

significant. A measured sample of cleaned grain passes from the funnel

into the barrel which is then hung on the end of the scale; the weight

is then slid down the graduated ruler until it balances.

Another product was a grain tester scale [left], used

to work out the percentage weight of a sack of grain (in pounds per

bushel) after the grain husk, dust and dirt is removed, enabling the

true value of the sack to be calculated - the difference could be quite

significant. A measured sample of cleaned grain passes from the funnel

into the barrel which is then hung on the end of the scale; the weight

is then slid down the graduated ruler until it balances. | SMITH'S FLOUR DRESSING MACHINE Sir, —A few days ago I had occasion to call at the very extensive flour mills of Mr. Edward Hudson of Leeds, called the King's Old Mills, in which are 40 pairs of stones, besides a considerable number of presses for extracting the oil from rape and linseed. Among the many ingenious contrivances for facilitating the work, my attention was particularly taken up with a patent Flour Dressing Machine, the use of which must be of very extensive advantage to the miller. The patent was obtained by an ingenious man of the name of Smith, who resides in Bradford in Yorkshire; he has not introduced the machine many miles from his own town; and although it is the best piece of machinery of the kind I ever saw, I fear that for want of its merits being known to the trade, it will remain in oblivion. The great advantage this machine possesses over any other I have met with, is its being constructed entirely of iron and brass, so that it is not subject to warp and get out of truth, or to wear out, like those made of wood. It has also an appendage, which I never saw in any other flour dressing machines. Down the outside of the cylinder there is a round iron shaft, on which are fixed round brushes—which shaft is constantly revolving and brushes the flour out of the wire, while a slow motion given to the cylinder presents the surface of it to the brushes. When wheat is damp, a very great advantage will be found in keeping the wire constantly clear. By a contrivance in turning two or three screw nuts connected with the inner brushes, the arms can be lengthened or shortened, so as to make them press more ir less on the wire. The whole is considered a cheap piece of machinery, and likely to be very durable. I am informed that one of these valuable machines may be seen at the warehouse of Mr. Bryan Corcoran, No. 36, Mark-lane, London. By inserting this in your valuable Magazine, you will do a great service to millers, and, I hope, to the ingenious inventor of the patent flour dressing machine. Your obedient servant, W. R— C—. |

|

| BRYAN CORCORAN, WITT, AND CO. (Established upwards of a Century), Successors to and purchasers of the old-established business of Bryan Corcoran and Co., of Mark Lane, London, BUILDERS OF FRENCH MILLSTONES, CORN, FLOUR, RICE, AND PAPER MILL ENGINEERS, Wire Weavers and Workers, Millwrights, and General Mill Furnishers |

| BRYAN CORCORAN,

WITT, AND CO. (Late Bryan Corcoran and Co.), contractors to H.M.

GOVERNMENT. Prize Medal and Two Honourable Mentions, Paris, 1855; Honourable Mention, Vienna Universal Exhibition, 1873 ; Grand Gold Medal, Moscow Great Exhibition, 1872, |

| Messrs.

Corcoran, Witt, and Co., Stand No. 40, exhibited a grinding mill of

peculiar construction for producing semolina. The machine consists of a

circular iron pedestal carrying a bedstone built of French burr, with

spaces left between them. In these spaces are inserted cast iron frames

covered with wire gauze, the object being to let the flour and semolina

fall through the wire sieves as soon as they are separated from the

branny particles, and thus nothing but the bran comes out at the

circumference of the stone. Beneath the bedstone revolving drums are

placed nmning round on a table to collect and distribute the flour and

semolina; hammers are also provided to jar the sieves at intervals to

prevent their choking. Samples of semolina made by this machine were

exhibited, and appeared to be very good and clean. Messrs. Corcoran and

Witt also exhibited porcelain roller mills, the champion middlings

purifier, millstones, and other articles connected with mill

furnishing. |

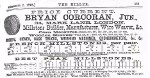

Alongside this, in 1878 Bryan Corcoran Jun

(as he billed himself for a time) included this advertisement

[left] for French and Peak District millstones. A later commentator

pointed out that this disproved any claim that French stones were

cheaper: a pair of 4' 4" French stones had a list price of between

£23/10/- and £35/5/-, while a pair of 4' 4" finished Peak stones had a

list price of £12. This, he said, should in fact be no surprise; the cost of transporting stones

would have been similar whatever they were made of, but to manufacture

a balanced millstone from blocks of chert must have required

considerable time and skill. As a result, French stones cost twice as

much as Peaks, but were clearly what late 19th century millers wanted:

stones that did not discolour the flour and needed minimal maintenance.

It is interesting to note that a Peak stone 'in the rough' cost

£4/10/- and that 'facing, rounding and cutting out eye' only added a

further £1/1/-.

Ten years later, his prices were the same, but his 1888 advertisement

adds 'Roller Mills from

£30; also Iron Rolls & Porcelain Shells'. This (and the spat with

Wegemann above) foreshadows the revolution in British milling in the

last decade of

the 19th century, when roller mills replaced millstones of all kinds.

The

technology had been developed in central Europe in mid-century and was

perfectly suited to the age of steam power and mass-produced steel.

Alongside this, in 1878 Bryan Corcoran Jun

(as he billed himself for a time) included this advertisement

[left] for French and Peak District millstones. A later commentator

pointed out that this disproved any claim that French stones were

cheaper: a pair of 4' 4" French stones had a list price of between

£23/10/- and £35/5/-, while a pair of 4' 4" finished Peak stones had a

list price of £12. This, he said, should in fact be no surprise; the cost of transporting stones

would have been similar whatever they were made of, but to manufacture

a balanced millstone from blocks of chert must have required

considerable time and skill. As a result, French stones cost twice as

much as Peaks, but were clearly what late 19th century millers wanted:

stones that did not discolour the flour and needed minimal maintenance.

It is interesting to note that a Peak stone 'in the rough' cost

£4/10/- and that 'facing, rounding and cutting out eye' only added a

further £1/1/-.

Ten years later, his prices were the same, but his 1888 advertisement

adds 'Roller Mills from

£30; also Iron Rolls & Porcelain Shells'. This (and the spat with

Wegemann above) foreshadows the revolution in British milling in the

last decade of

the 19th century, when roller mills replaced millstones of all kinds.

The

technology had been developed in central Europe in mid-century and was

perfectly suited to the age of steam power and mass-produced steel.|

MALT KILNS ERECTED with any number of floors ~

NEW FLOORS ADDED and existing kilns improved

The preference for double-floor malt kilns has steadily increased since the first was fixed by B. Corcoran in 1881 Galvanized Wire Dissipator ~ Barley Screens ~ Barley Washing & Drying Machines ~ Machines for extracting half-corns Corcoran's tin and wood shovels - and all apparatus and tools for malting, &c. |

Left is

an oat crusher of around 1900, manufactured by Richmond & Chandler

of Manchester, but with two plates on the hopper, one stamped No 1 P.R. Patent and the other Bryan Corcoran Ltd., 31 Mark Lane London. His

advertisements (note the small but significant changes over the years) show that he had established his works and warehouse in

Backchurch Lane - so he finally becomes part of our parish story!

Left is

an oat crusher of around 1900, manufactured by Richmond & Chandler

of Manchester, but with two plates on the hopper, one stamped No 1 P.R. Patent and the other Bryan Corcoran Ltd., 31 Mark Lane London. His

advertisements (note the small but significant changes over the years) show that he had established his works and warehouse in

Backchurch Lane - so he finally becomes part of our parish story!Back to Backchurch Lane | Back to History