History

of the parish & its principal church

- This

page includes many links to external sites giving more detailed information, shown in blue. [See this article, from East End Life.]

- Others

are to additional pages on this site, including texts

of original

documents, shown in green; they are also shown on the sitemap.

- Click on any image to enlarge.

Note

that down

the years many street names have changed. The first major renaming

scheme was started in 1857 by

the Metropolitan Board of Works, encouraged by the General Post

Office, after the MBW was established by the Metropolis Management Act

of 1855 (postal districts were introduced in the following year).

Another took place in the 1890's, after the London County Council was

formed, and the next

big scheme occurred between 1929-45. Streets were often re-named after

local 'worthies', whose stories are told on the various history pages.

Click right for street lists of 1913, 1919 and 1923. See here for details of a few sites on the western edge which now fall within the City of London, rather than Tower Hamlets.

Note

that down

the years many street names have changed. The first major renaming

scheme was started in 1857 by

the Metropolitan Board of Works, encouraged by the General Post

Office, after the MBW was established by the Metropolis Management Act

of 1855 (postal districts were introduced in the following year).

Another took place in the 1890's, after the London County Council was

formed, and the next

big scheme occurred between 1929-45. Streets were often re-named after

local 'worthies', whose stories are told on the various history pages.

Click right for street lists of 1913, 1919 and 1923. See here for details of a few sites on the western edge which now fall within the City of London, rather than Tower Hamlets.

St George-in-the-East was a civil registration

district (as well as an ecclesiastical parish) 'in the county of

Middlesex' from 1837 to 1889, and in the 'county of London' from 1889

to 1925, when it was designated as 'Stepney'.

THE

EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

After

Queen Anne came to the throne (1702-14), under the terms of the Acts of

Settlement designed to ensure the Protestant succession, and the Tories

took power after 22 years of Whig rule, a New

Churches in London &

Westminster Act

of 1710/1711 was passed, establishing a Commission to build fifty new

churches in populous districts. [See here for details of a 2011 Walk which marked its 300th anniversary.] The agenda was as much political as

pious: imposing edifices towering

over the homes of the working classes as a sign of the national religion -

especially needed, it was believed, in the East End where immigration

was taking hold and there were many dissenting conventicles. (This is

why episcopal mitres feature in the decoration of the apse, and no doubt why the dedication to St George was chosen.) They were

to be funded from a tax on coal and culm (a form of anthracite) - in theory, an infinite budget, but

only twelve (including St George-in-the-East) were ever completed. All

ran way over budget, and the scheme came to an end. There is much more

about

the architectural rationale, and Nicholas Hawksmoor the architect of

six of these churches, on

the Church & Churchyard page.

After

Queen Anne came to the throne (1702-14), under the terms of the Acts of

Settlement designed to ensure the Protestant succession, and the Tories

took power after 22 years of Whig rule, a New

Churches in London &

Westminster Act

of 1710/1711 was passed, establishing a Commission to build fifty new

churches in populous districts. [See here for details of a 2011 Walk which marked its 300th anniversary.] The agenda was as much political as

pious: imposing edifices towering

over the homes of the working classes as a sign of the national religion -

especially needed, it was believed, in the East End where immigration

was taking hold and there were many dissenting conventicles. (This is

why episcopal mitres feature in the decoration of the apse, and no doubt why the dedication to St George was chosen.) They were

to be funded from a tax on coal and culm (a form of anthracite) - in theory, an infinite budget, but

only twelve (including St George-in-the-East) were ever completed. All

ran way over budget, and the scheme came to an end. There is much more

about

the architectural rationale, and Nicholas Hawksmoor the architect of

six of these churches, on

the Church & Churchyard page.

When

the church was consecrated on 19 July 1729, parts of 'Wapping-Stepney' were still

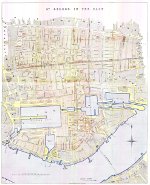

semi-rural, with open fields, but the area was beginning to develop. Right is

Roque's map of 1746.

Merchants who were building houses nearby, or came from further afield,

attended church in their

carriages (in 1739 only seven of the 2484 inhabitants of London that

'kept

coaches' lived in the parish), and access into the church was socially

segregated. The

local trades were ship-rigging and rope-making, of which

names like Cable Street and Ropewalk Gardens are a reminder - Cable

Street was once the length of the standard cable measure, 600 feet

[180m], with a ropewalk directly to the north of the church. From the

middle of the century hovels appeared in the marshlands behind

Pennington Street, which soon became wholly built over. By 1780 there

were 300 houses; by 1800, an average of 500-600 baptisms (rising

to over 1,000 two decades later, before daughter churches were built),

and

400-600

burials a year. The parish in those days extended down to the river:

the old parish of St John Wapping only covered a small area. In 1766 a

committee drawn from both parishes met to determine a procedure for

settling any disputes over 'bounds and boundaries'.

When

the church was consecrated on 19 July 1729, parts of 'Wapping-Stepney' were still

semi-rural, with open fields, but the area was beginning to develop. Right is

Roque's map of 1746.

Merchants who were building houses nearby, or came from further afield,

attended church in their

carriages (in 1739 only seven of the 2484 inhabitants of London that

'kept

coaches' lived in the parish), and access into the church was socially

segregated. The

local trades were ship-rigging and rope-making, of which

names like Cable Street and Ropewalk Gardens are a reminder - Cable

Street was once the length of the standard cable measure, 600 feet

[180m], with a ropewalk directly to the north of the church. From the

middle of the century hovels appeared in the marshlands behind

Pennington Street, which soon became wholly built over. By 1780 there

were 300 houses; by 1800, an average of 500-600 baptisms (rising

to over 1,000 two decades later, before daughter churches were built),

and

400-600

burials a year. The parish in those days extended down to the river:

the old parish of St John Wapping only covered a small area. In 1766 a

committee drawn from both parishes met to determine a procedure for

settling any disputes over 'bounds and boundaries'.

The

original organ, of 3 manuals with 25 speaking stops, was installed in

1733 by Richard Bridge (d.1758) of Clerkenwell. A contemporary commentator,

whose identity and credentials are uncertain, described it as a very plain instrument.

(Bridge's most famous organ - currently under restoration - was for

another Hawksmoor church, Christ Church Spitalfields, where the

Huguenot Peter Prelleur was organist - as well as writing theatre music.) The first organist of St George-in-the-East, appointed in

1738, was John

James,

formerly of St Olave Southwark and possibly a trumpeter in the King's

Musick. He was a star performer with a

reputation for improvisation - it's said that Handel, Geminiani,

Roseingrave, Greene, Pepusch and Boyce all heard him play. His

voluntaries were taken up by other organists (one of them was taken for

Handel's work) - they were said to be popular with ‘every deputy

organist in London’ - and many survive because they combine inventive

harmonic sequences with a good grasp of fugal technique. But he had his wilder side,

enjoying bull-baiting and dog fights, and according to Sir John Hawkins he indulged an inclination to spiritous liquors of

the coarsest kind, though Hawkins admitted that he was distinguished by the singularity of his style, which was learned and sublime. He died in 1745. (See here for the later history of Bridge's organ.)

On Sunday

1 October 1738 John Wesley preached at the morning and afternoon

services at the church - details here.The Gentleman's Magazine (vol 37) reported that on 4 March 1767 a private papist mass-house, which was kept at the back part of the house of a tradesman near Salt-petre bank [now Dock Street] was

suppressed: about twenty mean-dressed people, with the priest, were

assembled; but on the alarm of peace officers, made their escape at a

back door - see here for more about the history of the Roman Catholic presence in the parish.

Charity schools were established in the parish - see here for an account of Raine's Foundation institutions from 1719 onwards, and here for the school founded in 1781 by the Middlesex Society, and also for an overview of all the subsequent educational foundations. As

with some other new East London parishes of this period, St

George-in-the-East, though within the diocese of London, was exempt

from the jurisdiction of any archdeacon, and this anomaly remained into

the 19th century. The Vestry combined ecclesiastical and local

government responsibilities, and was 'general' (as opposed to 'select',

as elsewhere), open to all who paid 2s. or more per month for poor relief. Robert Seymour's 1835 Survey of the Cities of London & Westminster

- a part-published update of the work of the Elizabethan chronicler

John Stow - gives details of the officers it continued to appoint: 2

Churchwardens and 4 Overseers (the senior 'parish officers') and - from the lower

and middling ranks of society - 1 Constable, 13 Headboroughs (subordinates to the Constable, responsible for law enforcement), 4

Scavengers (responsible for keeping the streets clean), and 2 Surveyors

of the Highway ('peace officers'). As explained here, men were sometimes elected as

councilmen and aldermen who did not wish to serve for business or

religious reasons, in which case they could pay a fine to be exempted. The

parish was divided into two divisions, the upper and lower town

(Seymour lists the streets in each). Edward Scott was elected

Scavenger for the upper division of the parish in 1732, and Thomas

Saunders of the lower division in 1748. Left is

a challenge of 1754 on the regularity of the appointment of the

overseers of the poor, and on their assessments (claiming that the

well-to-do have been undercharged and the less affluent overcharged) -

a transcript can be read here. The first parish clerk was Samuel Bright, formerly a barber and periwig-maker: the Vestry determined that this should be a full-time post. His successor was Thomas Harmer Lacon (buried in a vault in the crypt in 1821, aged 65). Both of them frequently signed as witnesses in the marriage registers. See here for an account of the dismissal of Joseph Mee as grave-digger and bell-ringer in 1766. (Seymour also noted that 'Prayers are held on Wednesdays, Fridays, and Holidays [sic] about 11 o'clock, no Organ [but see above], one Bell'.)

As

with some other new East London parishes of this period, St

George-in-the-East, though within the diocese of London, was exempt

from the jurisdiction of any archdeacon, and this anomaly remained into

the 19th century. The Vestry combined ecclesiastical and local

government responsibilities, and was 'general' (as opposed to 'select',

as elsewhere), open to all who paid 2s. or more per month for poor relief. Robert Seymour's 1835 Survey of the Cities of London & Westminster

- a part-published update of the work of the Elizabethan chronicler

John Stow - gives details of the officers it continued to appoint: 2

Churchwardens and 4 Overseers (the senior 'parish officers') and - from the lower

and middling ranks of society - 1 Constable, 13 Headboroughs (subordinates to the Constable, responsible for law enforcement), 4

Scavengers (responsible for keeping the streets clean), and 2 Surveyors

of the Highway ('peace officers'). As explained here, men were sometimes elected as

councilmen and aldermen who did not wish to serve for business or

religious reasons, in which case they could pay a fine to be exempted. The

parish was divided into two divisions, the upper and lower town

(Seymour lists the streets in each). Edward Scott was elected

Scavenger for the upper division of the parish in 1732, and Thomas

Saunders of the lower division in 1748. Left is

a challenge of 1754 on the regularity of the appointment of the

overseers of the poor, and on their assessments (claiming that the

well-to-do have been undercharged and the less affluent overcharged) -

a transcript can be read here. The first parish clerk was Samuel Bright, formerly a barber and periwig-maker: the Vestry determined that this should be a full-time post. His successor was Thomas Harmer Lacon (buried in a vault in the crypt in 1821, aged 65). Both of them frequently signed as witnesses in the marriage registers. See here for an account of the dismissal of Joseph Mee as grave-digger and bell-ringer in 1766. (Seymour also noted that 'Prayers are held on Wednesdays, Fridays, and Holidays [sic] about 11 o'clock, no Organ [but see above], one Bell'.)

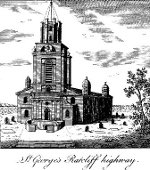

There were two

early medical charities

(unconnected with the church, though see here for an example of the involvement of a churchwarden with these two institutions, and with the emerging London Hospital - right in 1740s, with St George-in-the-East in the background:

There were two

early medical charities

(unconnected with the church, though see here for an example of the involvement of a churchwarden with these two institutions, and with the emerging London Hospital - right in 1740s, with St George-in-the-East in the background:

- the Eastern

Dispensary

(1782) - see here for details

- the Universal

Medical Institution

(1792)

on Old Gravel Lane, with 450 subscribers (president the Earl of Fife),

providing free advice,

medicine, cold, warm and vapour baths, inoculation and 'relief in cases

of suspended

animation' to all who attended at the 'proper hours' (viz. 9am-1pm and

3pm-5pm). Admission was on the recommendation of a Governor, and

out-patient visits were made within the limits of the Tower Hamlets.

By 1809 17,134 patients had been treated, of whom 14,978 were cured,

plus 841 midwifery cases; 460 were 'relieved' and 646 had died. 3,009 persons also had been inocutated with the cow-pox (see here for more on how vaccination replaced this practice of variolation).

Another

survival from this period - originally in the parish of St Mary Matfelon, then St Mark Whitechapel and

then St Paul Dock Street, and now part of this parish - is the Gunmakers' Company Proof House at

46-50 Commercial Road, of which there are more details and pictures here.

In the last decade of the century revolution was in

the air, because of events in France and rising taxation (the war with

France required an extra £2m) - more details here.

At St George's 47 special constables were sworn in to assist in

quelling any riots; the Vestry offered bounties to those who

volunteered to take the place of parishioners called up to serve in the

navy; and in 1795 a local branch of John Reeves' 'Church and King

militia', the Association for the Protection of Property against Republicans and Levellers, was formed, to mobilise against those who supported monstrous and nonsensical doctrines of equality. This

was followed by an armed association to protect life and property, for

which twenty men volunteered, providing their own uniform and arms.  A 1796 Act of Parliament required annual training, under the direction of the Constable of the Tower, of a regiment of the Tower Hamlets Militia (whose origins lay in the pre-Civil War 'Trayned Bandes'

to protect the Tower, taking the name of Tower Hamlets in 1605). The

Vestry objected (unsuccessfully) to the number called up - it was done

by ballot, with a quota from each of the Hamlets - complaining that

many inhabitants were ineligible, being seafaring persons, free watermen, labouring men with infirmities, and

undersized (particularly in the weaving manufactories), foreigners and

other exempted persons.

A further Act of 1813 extended their service liability to all parts of

the kingdom, and removed a previous anomaly which expressly excluded TH

militiamen's families from financial relief. The following year 25 men

served in the Waterloo campaign with the 3/14th Regiment of Foot ('A very Pretty Little Battalion').The First Regiment had its own March and Quickstep, by William Liquorish (a relative of Thomas Liquorish,

who had served with the Militia prior to serving as churchwarden),

published in 1796 in full score for regimental band and in piano

adaptation. [Shoulder belt plate from this period right - these were abolished in 1855.] The Militia office was in Wellclose Square.

A 1796 Act of Parliament required annual training, under the direction of the Constable of the Tower, of a regiment of the Tower Hamlets Militia (whose origins lay in the pre-Civil War 'Trayned Bandes'

to protect the Tower, taking the name of Tower Hamlets in 1605). The

Vestry objected (unsuccessfully) to the number called up - it was done

by ballot, with a quota from each of the Hamlets - complaining that

many inhabitants were ineligible, being seafaring persons, free watermen, labouring men with infirmities, and

undersized (particularly in the weaving manufactories), foreigners and

other exempted persons.

A further Act of 1813 extended their service liability to all parts of

the kingdom, and removed a previous anomaly which expressly excluded TH

militiamen's families from financial relief. The following year 25 men

served in the Waterloo campaign with the 3/14th Regiment of Foot ('A very Pretty Little Battalion').The First Regiment had its own March and Quickstep, by William Liquorish (a relative of Thomas Liquorish,

who had served with the Militia prior to serving as churchwarden),

published in 1796 in full score for regimental band and in piano

adaptation. [Shoulder belt plate from this period right - these were abolished in 1855.] The Militia office was in Wellclose Square.

Here are details of the Rectors and Lecturers of this period; here are details of many of the 18th century churchwardens; and here

is a 1795 account of the church, churchyard and other places of

worship in the parish. A fascinating article by Diana Markarill appeared

in The Ephemerist, no.148

(Spring 2010), based on the churchwardens' accounts for the late 18th

and early 19th centuries, for work on the bells and organ, the payment

of women for pew-opening duties [in 1729 the Vestry had agreed to have six and no more;

22 applied - tips made it a post worth having - and four women and two

men were appointed] and washing and mending linen, and for

various entertainments. Horwood's map of London (1792-99), updating

Roque, provides excellent detail. Developing areas not in the original

parish, but now within its boundaries though parish mergers, include Goodman's Fields, Rosemary Lane [Royal Mint Street] and East Smithfield (including the site of the Royal Mint built in 1809).

Gower's Walk Free School

was founded in 1808 - its remarkable story is told here.

The Royal Mint in East

Smithfield was rebuilt in 1809 and 1842. The nearby Shovel public house was the site of

an

early example of the racial tensions that were to beset the area: it

was reported that on 29 June 1787 local

constables were beaten and turned out of the pub by over 40 black

drinkers.

1811

saw the notorious Ratcliff

Highway murders, described in detail here

and here.

The events

highlighted the lack of any proper policing and detective service, and

this page describes the establishment of the Metropolitan Police in

1829, and the evolution of professionally-staffed magistrates' courts. Ten

years later, as

explained here, St

George-in-the-East Vestry was complaining about the expense of the

'Met', and

the fact that it had done nothing to reduce criminality in the area -

indeed, they believed it had made matters worse, and reduced the sense

of local

control; also, they said that the the officers were too military in appearance - see here to judge if that was true.

In

the years after the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, the Vestry protested

against high wheat prices at home, heavy import duties on imported

corn, and restrictions on foreign trade - which was to become a

recurring theme: in 1833 they took up the cause of the local sugar

trade

which was beginning to struggle. There were ongoing issues in relation

to the Docks - rates, and the impact on the coal trade. They were

exercised by the 1832

Reform Act and Poor Law

issues. And although the church bore the name of the Hanoverian

monarchs, they shared the national mood of disapproval of George IV, in

particular his treatment of his wife Queen Caroline, writing to her in

fulsome terms to declare their support - full text and more details here.

The

height of the parish's

prosperity was in the 1810-20's: see here

for some details of some of the residents of Cannon Street Road, and here

for Wellclose Square (at that time, outwith the parish). Here

is a description of the elaborate funeral

procession in 1824 for the

vicar of Tottenham, who was buried here in a family vault near the west

door. It contrasts

sharply with the very basic arrangements for most parishioners'

funerals!

The

early 19th century saw the rise of small local 'friendly societies'. Some began as pub-based drinking clubs that organised mutual welfare by

'passing the hat', becoming more organised through formal

subscriptions; they were later linked to the temperance movement, and

were controlled by legislation (they were the precursors of credit

unions). Two that met at the George Tavern in St George's Street in the

1830s were the Eastern Burial Society

and the True and Happy Friends

Benefit Society. Others had their origin in self-help associations within the Huguenot and Jewish communities. The

first Jewish friendly society, dating from 1812, was The Tent of Righteousness (which a century later invested £500 in the 4% Industrial Dwellings Company). By

the turn of the 20th century 15,000 Jews were actively involved in the

movement (two small local examples were the Podembitzer Friendly Sick Society at 135 Cannon Street Road and the Plotzkar Relief & Sick Benefit Society at the Kinder Arms, Little Turner [Rampart] Street); the Grand Order of Israel and Shield of David Friendly

Society is the last survivor, with four lodges still operating, mainly as

social clubs. See here for a later Rector's desire (1875) that well-run penny banks should replace the plethora of local institutions.

The Docks

Poverty and

deprivation was soon to take hold.

Rapid

social change was triggered by the expansion of

shipping, with its associated trades: see London and St Katharine's Docks (at the time, mainly in this parish but the area is now part of our daughter church St Peter London Docks). See here

for details of the legal battle between the Vestry and the Docks over

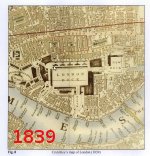

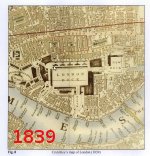

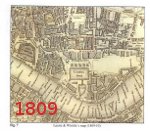

rates. Laurie and Whittle's map of 1809, and Crutchley's of 1839 [right] show the impact. Here is an 1810 list of authorised pilots, including many living in this parish, and here is the Watermen and Lightermen's Company 'Bum Book' listing boat owners and their details from 1839-59.

London Docks were

begun

in 1802 (Lord Sidmouth, First Lord of the Treasury,

laying the foundation stone on 26 June of that year, with 'genteel persons of both sexes' in attendance), and almost

immediately

enlarged; the adjacent St Katharine's Dock was opened in 1828. Vessels had to use the London Docks if

they

were bring tobacco or rice not of East or West India growth, or wine or

spirits; other cargoes could unload elsewhere. Specialist warehouses (for example, wool and tobacco),

and other trades, including the smelly sugar refining that

employed over 1,000 German workers, sprang up. The docks

brought incomers

from many other nations -

Greeks, Malays, Dutch, Scandinavians, Portuguese, Spanish and

French. Thomas de Quincey wrote in 1810 Lascars, Chinese, Moors, Negroes were met at every step. Dock

workers were poorly paid (5d. an hour) and poorly housed. An 1848

survey of 1651 heads of families living in the civil parish of St

George-in-the-East showed that dock work had become the majority

occupation, and two thirds of families existed on less than 25s. a

week, with only 17% earning over 30s. Boarding

houses, taverns and saloons brought crime. When Brian King became

Rector in 1842, there were said to be

154 brothels in the parish. Railways also began to criss-cross the

area.

Although the churches' main provision for seafarers' needs was centred in the

Dock Street area - details here

- there were two institutions, both in Cannon Street

Road: the Sailors' Rest Asylum (taken over from 'Bo'sun' Smith's

non-denominational mission in 1832) and a Sailors' Orphan Girls

Episcopal School and Asylum, set up in 1829. Both of these, and other provisions for the orphans of seamen, are

described here.

Civil administration and relief; public health

Civil registration

of births, marriages and deaths was introduced nationally from 1 July

1837, and many churches saw a major blip in baptisms in the preceding

days, because parents wanted to avoid the new system, and had got the

false impression that baptisms would in future cost 7s 6d, because the

Registrar would need to be present. (At Manchester Collegiate Church,

now the Cathedral, and in those days the sole parish for the city,

there were a staggering 7,285 baptisms that year.) At St

George-in-the-East there were 125 baptisms on 25 June, 149 on 28 June

and 163 on 30 June (compared with 105 for all the preceding weeks) -

see here

for more details of how this was handled. (A 1s or 1s 6d fee for

baptism - or at least, for registration and the clerk's attendance -

was common at the time despite being counter to church teaching that

the

sacraments should be available without charge; fees were made illegal

by the Baptism

Fees Abolition Act 1872.) See here for statistics, and also comments on non-Anglican marriages.

The local Registrars' statistics were used for a wide-ranging 1843

report on death rates, and funeral practice, across London. Figures for

1839 showed that the average age of death was the 24th lowest, out of

32, and that life expectancy for tradesmen was 13 years, and for

artisans 16 years, below average. John Verrall, the Registrar for the

St John's District (mainly Wapping), and also parish clerk of St

George's, commented on the causes of this: overcrowding, the ruinous

state of many houses, lack of drainage and ventilation, poor habits of

cleanliness, the number of lay-stalls [dungheaps], in which filth of all kinds is accumulated, and the number of pigs kept in the neighbourhood. See here for more details.

The

1831 census (and clerical directories for this period) gave the

population as 38,505, and poor relief

expenditure

for 1833-35 was £17,706 or 9s.2d. per ratepayer. (In 1739 the figure had been £1,046 10s 4d.) In 1836,

the parish was constituted as a Poor Law parish

under the 1834 Poor

Law Amendment Act,

administered by 18 elected Guardians. Several of these had also served

as churchwardens of the parish (a higher proportion than in other districts) - for example, William Stutfield in 1843, and Thomas Liqorish in 1844. They took over responsibility for the parish workhouse in Wapping, and authorised £2,000

for

its extension. By 1847 the population was 47,362 but expenditure was

slightly down - £16,474. In

1851 they built an industrial school at Plashet, and also operated a

'casual ward' for vagrants in Raymond Street, off Green Bank, Wapping.

By 1861 the population was 48,891. An infirmary was added to the workhouse in 1871. See here

for fuller details, and the subsequent history, of these various

institutions, and the reason why, though in the 1840s their spending on

'out-relief' was in line with other unions (though fell sharply a

generation later, under the local influence of the nascent Charity Organisation Society), their 'in-relief' spending - on the workhouse and its inmates - was much higher than average.

In

1844 the Association for Promoting

Cleanliness among the Poor

built baths and a laundry for the 'destitute poor'

in

Glasshouse Yard [now John Fisher Street], which was used by 27,662

bathers and 35,480 washers in

its first year. Bathers and washers paid one penny, ironers a farthing.

The Association also provided whitewash, and lent buckets and pails.

Its success led to an Act of Parliament in 1846 'To encourage the

Establishment

of Baths and Wash-houses', funded from the rates. See here

for the major part that William

Quekett, Lecturer and Curate of the parish, played in this - against initial opposition from the parish vestry - arguing that it was both philanthropic and would in the long term bring

savings to ratepayers [1846 handbill right]. In Curiosities of London: Exhibiting the Most Rare and Remarkable (1855), p33, John Timbs opined ...

so strong was the love of cleanliness thus encouraged that women often

toiled to wash their own and their children's clothing, who had been

compelled to sell their hair to purchase food to satisfy the cravings

of hunger. However, in 1850 the Vestry passed a resolution

objecting to the establishment of further facilities in the parish.

In

1844 the Association for Promoting

Cleanliness among the Poor

built baths and a laundry for the 'destitute poor'

in

Glasshouse Yard [now John Fisher Street], which was used by 27,662

bathers and 35,480 washers in

its first year. Bathers and washers paid one penny, ironers a farthing.

The Association also provided whitewash, and lent buckets and pails.

Its success led to an Act of Parliament in 1846 'To encourage the

Establishment

of Baths and Wash-houses', funded from the rates. See here

for the major part that William

Quekett, Lecturer and Curate of the parish, played in this - against initial opposition from the parish vestry - arguing that it was both philanthropic and would in the long term bring

savings to ratepayers [1846 handbill right]. In Curiosities of London: Exhibiting the Most Rare and Remarkable (1855), p33, John Timbs opined ...

so strong was the love of cleanliness thus encouraged that women often

toiled to wash their own and their children's clothing, who had been

compelled to sell their hair to purchase food to satisfy the cravings

of hunger. However, in 1850 the Vestry passed a resolution

objecting to the establishment of further facilities in the parish.

In 1848 the Quarterly Journal of the Statistical Society of London

(founded in 1834, now the Royal Statistical Society) demonstrated this new scientific method by publishing

a detailed report into the 'state of the poorer

classes', which can be viewed here, based

on the St Mary's sub-district

of the civil parish - chosen, they said, not because it was the worst

slum area in London (the extremes of overcrowding and poverty were to

come later) but because it was typical, and they were concerned to make

positive suggestions for improvement. They were motivated as much by public policy (avoiding civil unrest) as by philanthropic solicitude. Data

collected in 1845 was analysed in 27 tables, the latter

part of the report being particularly concerned to correlate the age of

parents with family size, mortality rates and health.

Local

government in London was chaotic, with various self-selected boards and

committees responsible for poor relief, highways and sewerage. For instance, there

were 136 Commissioners

for Sewers

for the Tower Hamlets, with a local office in Alie Street. There

were many fires in the area, but firefighting was unco-ordinated:

parishes had their own engines, as did insurance companies. See here for

a note on the development of the London Fire Brigade, and here for details of a local 18th century manufacturer of fire engines (who was churchwarden here in 1784).

The main authority was the

Public Vestry,

elected each Easter by ratepayers. Sir Benjamin

Hall's Metropolis

Management Act of

1855 swept these away and created a Select

Vestry

(chaired by the

incumbent) and Boards for each parish. See here

for more details of this 'incorporation', in a restrospective paper of 1880 by the Vestry Clerk. (It also created the Metropolitan Board of Works - see here for details of its first clerk, later a local police court judge.) In 1856 the High Court dealt

with a dispute between the new Vestry and London Docks over the rate

levied on the Docks for street paving. It took over responsibility for

the local section of the Commercial Road when tolls were abolished in

1865. There was continued scope for electoral corruption where voters

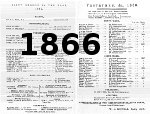

were illiterate - left

is a completed voting paper for the 1862 vestry, together with lists of

parish officers for 1866 and 1871 (note the change from 'Vestrymen' to

'Guardians of the Poor'). More details of many of these men are given here. The clerk - usually full-time, and often a solicitor (as with W.L. Howell,

in post at the time of the Ritualism Riots; he was also the Registrar

for one of the sub-districts of Gt George's East) - was a key

person. Salaries for this post varied widely, depending on local

history and the energy and contacts of the postholder;

here he was paid £500 but had to pay his staff from this (as did his

counterparts at Bethnal Green, on £750, and St Luke Old Street, on

£800).

The main authority was the

Public Vestry,

elected each Easter by ratepayers. Sir Benjamin

Hall's Metropolis

Management Act of

1855 swept these away and created a Select

Vestry

(chaired by the

incumbent) and Boards for each parish. See here

for more details of this 'incorporation', in a restrospective paper of 1880 by the Vestry Clerk. (It also created the Metropolitan Board of Works - see here for details of its first clerk, later a local police court judge.) In 1856 the High Court dealt

with a dispute between the new Vestry and London Docks over the rate

levied on the Docks for street paving. It took over responsibility for

the local section of the Commercial Road when tolls were abolished in

1865. There was continued scope for electoral corruption where voters

were illiterate - left

is a completed voting paper for the 1862 vestry, together with lists of

parish officers for 1866 and 1871 (note the change from 'Vestrymen' to

'Guardians of the Poor'). More details of many of these men are given here. The clerk - usually full-time, and often a solicitor (as with W.L. Howell,

in post at the time of the Ritualism Riots; he was also the Registrar

for one of the sub-districts of Gt George's East) - was a key

person. Salaries for this post varied widely, depending on local

history and the energy and contacts of the postholder;

here he was paid £500 but had to pay his staff from this (as did his

counterparts at Bethnal Green, on £750, and St Luke Old Street, on

£800).

St George's Town Hall

on Cable Street was originally the Vestry Hall, built in 1861 at a cost of

£6,000. (Prior to this the Vestry met in a room on the south-west corner of the church.) Left are

details of contracts entered into by the Vestry in 1862 and 1864 for

public works, including street lighting, 'cleansing and watering' the

streets and 'removal of dust', paving and sewerage, and work on the

Vestry Hall. See here

for the story of William Cooke, one of the three parish rate

collectors in 1866, who held various other offices in the parish in his

time, and was also an undertaker. Right is a ticket for a dinner held there in 1874 to mark the Duke of

Edinburgh's marriage. [The

1899 London

Government Act

replaced Vestries with 28 Borough Councils,

when the new Stepney Borough

Council took over the building as a local Town Hall; since the creation

of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in 1963 it is now used for

a variety of local projects.] Some local streets bear vestry members' names: for

example, Fairclough [formerly North], Dellow [formerly Victoria] and Stutfield [formerly Elizabeth] Streets.

St George's Town Hall

on Cable Street was originally the Vestry Hall, built in 1861 at a cost of

£6,000. (Prior to this the Vestry met in a room on the south-west corner of the church.) Left are

details of contracts entered into by the Vestry in 1862 and 1864 for

public works, including street lighting, 'cleansing and watering' the

streets and 'removal of dust', paving and sewerage, and work on the

Vestry Hall. See here

for the story of William Cooke, one of the three parish rate

collectors in 1866, who held various other offices in the parish in his

time, and was also an undertaker. Right is a ticket for a dinner held there in 1874 to mark the Duke of

Edinburgh's marriage. [The

1899 London

Government Act

replaced Vestries with 28 Borough Councils,

when the new Stepney Borough

Council took over the building as a local Town Hall; since the creation

of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in 1963 it is now used for

a variety of local projects.] Some local streets bear vestry members' names: for

example, Fairclough [formerly North], Dellow [formerly Victoria] and Stutfield [formerly Elizabeth] Streets.

It

was the

Vestry that elected churchwardens for the

parish each year. Wardens did not have to be members of the Church of England (for example, Elijah Goff,

warden 1797 and 1798, was a member of the Presbyterian chapel in Broad

Street, and others had no religious affiliation). Meetings could be

'packed' to secure the appointment of

wardens hostile to the church and Rector, as happened regularly in the

coming years, particularly when Bryan King was Rector. [Even though Parochial

Church Councils were created by the 'Enabling Act' of

1919, churchwardens are still technically appointed by residents of the

parish rather than church members, though these days this is mainly a

technicality, and wardens have to be 'actual communicants' in the Church of England.]

Under

the 1855 Act, Medical Officers of

Health

were appointed for each

District. The Registrar General published weekly, monthly and annual

Tables of births and deaths, classified by causes - see here

for the

1858 categories. ('Bills of Mortality' had been published in London

since the late 16th century.) For example, in the first quarter of 1858

in the St George-in-the-East District there were 55 deaths from

measles, 12 from scarlatina, 45 from whooping cough, 2 from diarrhœa

and 7 from typhus; 26 men and 39 women died in the parish workhouse: see here

for the full figures. It was the only district where the rate of deaths

from scarlet fever fell between 1851-60 and 1861-70. The MoH's annual report was published by the Vestry.

The

population of the civil district of St George-in-the-East given in the

1861 census was 48,961, of whom 31,106 (65.58%) were born locally, 4004

(8.19%) in Ireland, and 2,361 (4.83%) in 'foreign parts'.

The Metropolitan Sanitary Commission had made its first report in 1848 - see here

(p17) the evidence of R. Bowie, surgeon, who had been practising in

Burr Street, East Smithfield, at the time of the 1832 cholera outbreak.

Between 1854-55

the quality of water provided by the various companies was monitored,

and reported to the General Board of Health (Medical Council) - this

was to become significant in checking the spread of the disease, which had

previously been thought to be transmitted by air rather than water (see Steven JohnsonThe Ghost Map (Penguin 2008) for an

imaginative account of this issue). Two

samples from the East London Company produced a scary

result [right]. See here

for the gruesome story of Aldgate Pump, far right in 1908 (at the junction of Fenchurch

and Leadenhall Streets: 'east of Aldgate Pump' became a common term for

the East End), and its historical associations. Its 'mineral salts'

were prized until it was

discovered that this was the result of calcium from human bones

leeching into the water; it was connected to a mains supply in 1876.

Another cause of death, common in this area, was the result of baby farming,

whereby daily nurses were hired to take charge of the unwanted children

of prostitutes and others, on the tacit understanding that they would

die of neglect and starvation (often recorded as 'marasmus'). The

practice was exposed by the journalist James Greenwood as one of The Seven Curses of London (Stanley Rivers 1869, chapter 3) and is explored is this paper by Dorothy Haller.

Linked to the new public health provisions were slum clearance

powers. Under the 'Torrens Acts' (the Artisans and Labourers' Dwellings

Act 1868, amended 1879 and 1882 - resulting in the curious 'short'

title 'Artisans* and Labourers Dwellings Act (1868) Amendment Act (1879)

Amendment Act (1882)' - owners could be

forced to repair or to demolish

individual dwellings, though the provisions for rehousing that

would have given it 'teeth' failed

to get through Parliament. (William Torrens was the Liberal MP for Finsbury at the time.) More significantly, the 'Cross Acts' (the Artisans* and

Labourers Dwellings Improvement Act 1875, amended 1879 and 1882) enabled compulsory purchase of whole

areas, with landowners compensated (R.A. Cross was Disraeli's Home Secretary).  The St George-in-the-East

Vestry was among a number of local authorities that, for various

reasons, made limited use of these powers. However, see here

for the Rector's delight at the condemning of over 200 of properties by

our Medical Officer of Health immediately after the passage of the 1875

Act; here for details of the Whitechapel Estate, a major '5% philanthropy' scheme

just outside the civil parish (and now within the ecclesiastical

parish), promoted by the Metropolitan

Board of Works and the Peabody Trust; and here

for the adjacent Katharine Buildings project in Cartwright Street,

creating housing for those beyond the reach of

other providers. The legislation was consolidated

as Parts I and II of the 1890

Housing of the Working Classes Act.

The St George-in-the-East

Vestry was among a number of local authorities that, for various

reasons, made limited use of these powers. However, see here

for the Rector's delight at the condemning of over 200 of properties by

our Medical Officer of Health immediately after the passage of the 1875

Act; here for details of the Whitechapel Estate, a major '5% philanthropy' scheme

just outside the civil parish (and now within the ecclesiastical

parish), promoted by the Metropolitan

Board of Works and the Peabody Trust; and here

for the adjacent Katharine Buildings project in Cartwright Street,

creating housing for those beyond the reach of

other providers. The legislation was consolidated

as Parts I and II of the 1890

Housing of the Working Classes Act.

[ * Sometimes spelt 'Artizans'] Right is the famous illustration 'Over London - By Rail' by Gustave Doré in Blanchard Jerrold's London - A Pilgrimage (1872).

The age of district churches, and buildings

The age of district churches, and buildings

Although

the parish was geographically small (just 244 acres), by the

mid-19th century it had become densely populated, and much energy

went into building, or taking over from other denominations, additional

churches - some of which became separate parishes. Each of them had its

complement of halls, institutes, schoolrooms and other premises. Click

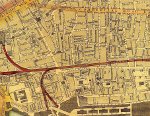

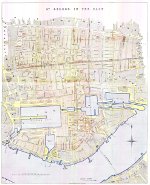

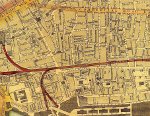

on the links for details of each of them, and here for details of baptism and weddings registers. This 1862 map shows

the

churches nearest to St George's, and this 1878 map

[right] gives a detailed picture of the area for which the Vestry was

responsible (which included the area of the 'daughter' churches, and

most of Wapping).

Anglican churches or

parishes founded by St George-in-the-East

|

Two further

parishes were later incorporated into

St George's parish (and the boundary with St Peter London Dock was

adjusted in

1989, transferring the St Katharine's Dock area to St Peter's):

former Anglican

parishes which are part of the present-day parish

|

In

the 17th and 18th century dissenters, and churches serving foreign

nationals, were rather more active locally than the Church of England

or the Roman Catholic Church. By the middle of the 19th century that

had changed; in answer to the question posed in 1851 Are there may Dissenters in your

parish? Bryan King

observed (though how accurately?) There

are not many DIssenters; in fact, the people are too poor to support

either Dissenters or any teachers without extraneous aid. However, there had been a huge variety of such

places of worship in the parish, chronicled here:

(former)

churches of other denominations

|

There

are also pages about the history and growth of various areas of the

present-day parish (some of them previously in adjacent, now merged, parishes):

- Precinct of Wellclose, once a Liberty of the Tower of London, and

Wellclose Square, a centre of 'liberty'

- Goodman's Fields

- theatres, Prescot Street, Leman Street

- Magdalen Hospital for the reception of Penitent Prostitutes

- East Smithfield, including the Royal Mint

- Ratcliff Highway, including the famous murders of 1811-12

- Cable Street

from earliest times to the present day

- Rosemary Lane

and Rag Fair

- Backchurch Lane and Pinchin Street

- St John's parish

- Cannon Street Road and Ponler Street

- Sugar Refining; Wool and Tobacco warehouses

- housing - Peabody Estate, Katharine Buildings, and for a much later period St George's Estate

- Hessel Street

- a centre of Jewish life

- Synagogues

throughout the parish, reflecting the steady growth of its Jewish

population

- Watney Street

- Chapman Street [now Bigland Street] area

- Schools in the parish

- Workhouse and Infirmary

- The Fortunes of the clergy - an explanation of the history of stipends and the struggle to make ends meet

- Churchwardens and their families - 18th century and 19th century

|

At

the time of the Great Exhibition of 1851* (when Dr Worthington,

incumbent of Trinity Church, Gray's Inn Road, offered to conduct

services, if

required, in the Greek, Latin, French or Italian tongues)

a booklet of service times throughout London was published by Sampson

Low. It lists the services for this parish as

¶ George's,

St., in the East, parish church. Between 9 and 10, Cannon

street.

Revs. B. King, rector; W. Quekett, lecturer. 11, morning ;

3½, afternoon. Lord's supper, first Sunday in

month.

¶ Christ

Church,

Watney street, Commercial road, East. Revs. W. Quekett,

incumbent; G.

Mockler, curate. 11, morning; 3½, afternoon; 6½,

evening.

Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saints' days, 11, morning. Lord's supper,

last Sunday in month — Seats to be had of Mr. C. J. Osborne,

18,

Cannon street.

¶ St.

Mary's, Johnson street, Commercial road east. Rev. W.

M'Call,

incumbent. 11, morning ; 6½, evening. Thursdays, 7, evening.

Lord's

supper, first Sunday in month, after morning service; third ditto,

8¼, morning. There is also a service on the fourth Sunday in

month,

3, afternoon. — Seats to be had after the Thursday

service.

¶ St.

Matthew's Episcopal Chapel, Pell street, St. George street, near

Wellclose square. Rev. D. Moore, minister. 11, morning;

6½,

evening. Lord's supper, second Sunday in month. — Seats may

be had

of Mr. Butler, 42, Wellclose square.

¶ Trinity Episcopal

Chapel,

Cannon street road. Rev. H. Robbins, incumbent. 11,

morning; 6½,

evening. Wednesdays, 7, evening. Lord's supper, third Sunday in

month.— Seats to be had of the chapelwarden.

|

[*

In 1857 William Quekett, who had served energetically in this parish

but was by then the Vicar of Warrington, organised a grand railway

excursion from there to London to see the sights, including the Crystal

Palace from the Great Exhibition, by then relocated to Sydenham - you

can read about it here.]

The first-ever nationwide census of religious attendance was

conducted on Mothering Sunday 1851; here

are the figures for the borough of Tower Hamlets, with some comments. In 1859 there were 467 marriages in the

registration district of St George-in-the-East: 281 in the Church of

England, 172 Roman Catholic, 7 in other Christian churches and 7 under

the auspices of the Superintendent Registrar [i.e. civil ceremonies].

Ritualism Riots, 1859-60

The

one thing many people know about St George-in-the-East is that there

were riots in church over matters of ritual and ceremonial. It

is

an extraordinary tale, which has been extensively written about; you

can find a summary here.

We marked their 150th anniversary with a programme of special events, including a visit by the Archbishop of Centerbury.

Parish worship after 1860

After the riots, things calmed

down. Ironically, since those days worship at St George's

has been of a 'central' character, alongside our high and low church

neighbours! The pattern of Sunday worship in 1863, according to a somewhat cursory (and perhaps incomplete) Guide to the Church Services in London and its suburbs,

was 11am (HC on the first Sunday), 3.30pm and 7pm, with a weekday

service on Tuesday at 7pm. By 1875 - when Harry Jones had been Rector

for two years - it was

as follows (see also Dickens' Directory of London

for 1879):

| Services Sunday

HC 8.00, 1st S and greater festivals, 11.45, M 11.00, E with

churchings 3.00, E with baptism 4.15, E 7.00; Daily, M 11.00;

Festivals M 11.00, HC am. Choir, partly paid. Music, Anglican.

Surplice in pulpit. Seats 1200, all free. Offertory, at each service. |

Weekday Matins at 11am was a pattern in other parishes at

this period - and often well-attended. Note the inclusion of 'surplice

in pulpit', in the light of the Ritualism Riots. Seats...all free; offertory shows that the parish had managed to abolish pew rents, and took collections. See here

for the evidence presented by the Rev G.H. McGill of Christ Church

Watney Street (on behalf of Stepney deanery clergy) to the Select

Committee on the Ecclesiastical Commission in 1862, which gives

detailed facts and figures showing how hard it was to sustain parish

finances with uncollectable pew rents, practically no help from local

businesses, and limited or non-existent endowments in the new district

churches; and here

for the case made by Harry Jones in 1875 against the creation of

district churches, for a variety of reasons, including financial.

Schools

A

major change in education provision came with the 1870

Education Act - see here for details of its impact locally, and of all the Board Schools that were built in the parish and their subsequent fate.

Church and community

The parish workhouse and infirmary, and the poor law schools, loomed large in the local consciousness. Here

and here

are

the two parts of an 1866 newspaper article describing the

experience of a 'female casual' in the workhouse. Charles Dickens, in chapter 3 of The Uncommercial Traveller

(a collection of his sketches about various parts of London)

describes in graphic detail a visit to Wapping Workhouse - passing en route

'Mr Baker's trap', a site of many suicides named after the local

coroner; it makes grim reading, but he concludes that the workhouse was

an establishment highly creditable to those parts, and thoroughly well administered by a most intelligent master. He

called for an equalisation of Poor Law rates across London, finding it

absurd that the poorest districts had to find the highest rates: 5s.6d.

in the pound in one East End parish, as against 7d. in the pound in St

George Hanover Square!

By

1870, for the first time, the district was classed as one of the five

poorest in London. But the St George-in-the-East Poor Law Guardians

- like their counterparts in Stepney and Whitechapel - virtually ceased

making 'out-relief' payments (as opposed to

'in-relief' - the workhouses). This was partly because of the growing

influence of the Charity Organisation Society which

pressed for more targeted assistance.

By

1870, for the first time, the district was classed as one of the five

poorest in London. But the St George-in-the-East Poor Law Guardians

- like their counterparts in Stepney and Whitechapel - virtually ceased

making 'out-relief' payments (as opposed to

'in-relief' - the workhouses). This was partly because of the growing

influence of the Charity Organisation Society which

pressed for more targeted assistance.

John Marius Wilson's Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales (1870-72) gives the following statistics and other details:

Acres,

243. Real property in 1860, £182,734; of which £600 were in gas-works.

Population in 1851, 48,376; in 1861, 48,891. Houses, 6,169 ... The parish church ... is a noble and massive structure, in the Doric style;

has a lofty tower at the west end, unlike any other in England; has

also four smaller towers ... St. Matthew's church, in Pell-street, has a good spire ...

The head benefice is a rectory ... Christchurch, St Mary, and St. Matthew,

are vicarages, and St. Peter is a perpetual curacy ... Christchurch was constituted in 1841, St. Mary's in 1850; St.

Matthew's in 1860; St. Peter's, in 1866. Population of Christchurch, 13,145; of St. Mary, 5,515; of St. Matthew, 3 245; of St. Peter, 8,354.

Value of St. George, £396; of Christchurch, £300; of St. Mary, £150;

of St. Matthew, £183; of St. Peter, £420.

The places of worship,

in 1851, were 5

of the Church of England, with 5, 880 sittings; 1 of Independents, with

700 sittings; 1 of Baptists, with 560 sittings; 2 of Wesleyan

Methodists, with 1,550 sittings; 1 of New Connexion Methodists, with 92

sittings; 1 of Primitive

Methodists, with 337 sittings; 1 of Wesleyan Reformers, with 290

sittings; 1 of

Lutherans, with 150 sittings; 2 undefined, with 120 sittings; and 1 of

Roman

Catholics, with 360 sittings.

The schools were 9 public day schools, with 2,220 scholars; 86 private day schools, with 2,211 scholars; 13 Sunday

schools, with 3,053 scholars.; and 7 evening schools for adults, with 119

scholars.

The district is divided into the sub-districts of St. Mary, St.

Paul, and St. John; and is aggregately conterminate with the parish.

Acres of the sub-districts, 62, 84, and 97. Population 18,181; 21,015; and

9, 695. Houses, 2,384; 2,793; and 992. Poor-rates in 1862, £32,243.

Marriages in 1860, 410; births, 1,880 - of which 90 were illegitimate;

deaths, 1,293, - of which 671 were at ages under 5 years, and 12 at

ages above 85. Marriages in the 10 years 1851-60, 3,744; births, 18,743; deaths, 13,178. The workhouse is in St. John sub-district; and

had 304 male inmates and 514 female inmates at the census of 1861.

|

In 1883 St George's Mission House

at 136 St George's Street [later renumbered 181 The Highway] was built at the cost of £5000

- a susbstantial building on three floors with acommodation

above. Goad's 1887 insurance map show that it had a wine store to

the left, and a colour works and chemical packaging company on the

right, and the whole area around the south and west of the church was

built up. The hall

was demolished after 1962, when The Highway was widened. You

can still see the headstone of the rear door in the wall by the church [pictured] - a separately-listed feature.

In 1883 St George's Mission House

at 136 St George's Street [later renumbered 181 The Highway] was built at the cost of £5000

- a susbstantial building on three floors with acommodation

above. Goad's 1887 insurance map show that it had a wine store to

the left, and a colour works and chemical packaging company on the

right, and the whole area around the south and west of the church was

built up. The hall

was demolished after 1962, when The Highway was widened. You

can still see the headstone of the rear door in the wall by the church [pictured] - a separately-listed feature.

There was also a small parish room built on the north-west corner of

the Rectory, at some point before 1890 [plan of house and garden left] - when was it demolished?

There was also a small parish room built on the north-west corner of

the Rectory, at some point before 1890 [plan of house and garden left] - when was it demolished?

In

1891, at the time when St Matthew Pell Street closed as a church (though continued in use for other activities), Tait Street

Mission Room was built at a cost of £1050, of which £918 had

been raised by the time of its opening

by Princess Helene Frederica Augusta, Duchess of Albany. (Tait Street,

just beyond the railway to the east of Cannon Street Road, was

named after Archibald Campbell Tait, Bishop of London and later

Archbishop of Canterbury, who had visited the area during cholera

epidemics - though had done little to help the parish through the

Ritualism Riots.)

At

the opening ceremony the Rector said

The

room ... may be regarded as a daughter mission room to the larger one

[on The Highway] ..... In the organisation of the parish it will take

the place of an Arch of the Blackwall Railway where for the last two

years a successful mission work has been carried on. This arch is now

required for the purposes of the Railway and it has been necessary to

find other quarters for the mission. The Walburgh Street Arch is not

given up without regret, for there are many who have cause to remember

with much thankfulness its happy success; but it must be confessed that

a Railway Arch with its constant noise of trains rumbling overhead and

with its cold draughtiness is not a convenient place either for

services or for meetings, and there is every reason to hope that the

good work will be continued with even an increased success in the Tait

Street Mission Room ... The

room ... may be regarded as a daughter mission room to the larger one

[on The Highway] ..... In the organisation of the parish it will take

the place of an Arch of the Blackwall Railway where for the last two

years a successful mission work has been carried on. This arch is now

required for the purposes of the Railway and it has been necessary to

find other quarters for the mission. The Walburgh Street Arch is not

given up without regret, for there are many who have cause to remember

with much thankfulness its happy success; but it must be confessed that

a Railway Arch with its constant noise of trains rumbling overhead and

with its cold draughtiness is not a convenient place either for

services or for meetings, and there is every reason to hope that the

good work will be continued with even an increased success in the Tait

Street Mission Room ...

(The Mission Room was later taken on by the British Legion.)

|

As in many parishes, formal missions

were organised (though Harry Jones, Rector 1873-82, was not a fan - see why here).

In the major London-wide mission of 1884-5, the missioners appointed

for St George-in-the-East were the Revd W.M. Sinclair, Vicar of St

Stephen Westminster; for Christ Church, The Revd Wladislaw Somerville

Lach-Szyrma of St

Peter Newlyn, Penzance but later of Barkingside (his Polish father had

fled persecution and married into a naval family - several descendents

became Anglican clergy);

and for St John the Evangelist-in-the-East, The Rev E. Bickersteth,

Rector of Framlingham, and the Hon and Rev R. E. Adderley, Curate of

All Hallows Barking (both from famous clerical families, and

experienced mission speakers). [Right is the Advent programme for 1878, and an 1893 mission card.]

As in many parishes, formal missions

were organised (though Harry Jones, Rector 1873-82, was not a fan - see why here).

In the major London-wide mission of 1884-5, the missioners appointed

for St George-in-the-East were the Revd W.M. Sinclair, Vicar of St

Stephen Westminster; for Christ Church, The Revd Wladislaw Somerville

Lach-Szyrma of St

Peter Newlyn, Penzance but later of Barkingside (his Polish father had

fled persecution and married into a naval family - several descendents

became Anglican clergy);

and for St John the Evangelist-in-the-East, The Rev E. Bickersteth,

Rector of Framlingham, and the Hon and Rev R. E. Adderley, Curate of

All Hallows Barking (both from famous clerical families, and

experienced mission speakers). [Right is the Advent programme for 1878, and an 1893 mission card.]

In 1888 the British

Weekly

conducted a London-wide census of attendance at places of worship;

unlike that of 1851, it did not include Sunday School scholars. here

are the figures for the churches within the civil district of St

George-in-the-East (wider than the parish). It records attendances at

the parish church of 292 in the morning and 425 in the evening.

There

are various contemporary accounts of parish

life:

- In 1875 Harry

Jones, the Rector (who created St George's Gardens) published a

readable account East & West London

[included on this site over four pages] comparing the two worlds. (See further comment on Jones' style here.)

He

described the local trades (the German sugar refining trade collapsed

soon afterwards), and Jamrach's Emporium on The Highway, where you

could buy any kind of wild animal - see here for more details.

- Harry Jones also

commented on Charles Dickens' The Mystery of Edwin Drood, parts of which were set in an opium den in the

parish - though debate continues about the details. In 1884 he wrote Charles Dickens used to come here and grub for sensational localities. He found them. Dickens

had long visited the area - in 1860 he went to the female ward of the

workhouse. In a recent talk in church 'Charles Dickens and the East End

of London' Charles West said, appositely, that the East End's greatest

gift to DIckens was sharing the chalice of adversity.

- Charles Dickens

Jnr's Dictionary of

London (1879) describes the dancing-rooms and

cafés and opium dens of Ratcliff Highway; see here for his comments on one of its common lodging houses.

- In 1880 the curate

R.H. Hadden produced An East End Chronicle [link provides full transcribed text; it can also be viewed online here] which remains the most complete account of

the first 150 years of the parish. (The introduction was written by the

Rector, Harry Jones, who was travelling in Jerusalem at the time; proceeds of sale were for the organ

fund.)

- For some years from 1884 a monthly journal Eastward Ho! was published by Wells, Gardner, Darton & Co, as a medium of thought between East and West London, and

included graphic accounts of parish life, with appeals to university

men living and working in London to visit the area and get involved.

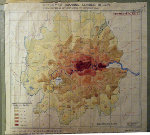

- Charles Booth's

1889 & 1898 Poverty

Maps

classified every street, and is a rich and fascinating

resource, not least for the contrast between his original research and

its update a decade later, based on detailed notes taken by inspectors

carefully walking each patch in the company of local

police officers. (Modern-day government pronouncements

about the lives of the 'undeserving poor' living on welfare show no

such rigour; despite an approach which was often equally patronising,

the Victorians had at least done their research thoroughly, and knew in

great detail

what life was really like.) Digitised facsimilies of some of these

survey

notebooks are also on the

Charles Booth site; a transcript of one of them, which also includes comments on the area, is here, and the 1888 list of tailors working in the parish is here.

The update

shows some improvements - which surely were in part the

result of

the intensive church presence and activity. In 1902 he published a

narrative account, based on observations from the previous few years;

the section relating to this area (with comments on Jewish settlement,

churches of various denominations, charities and local government) can

be read here.

- Here

is part of a somewhat pious and sentimental - but interesting in its

details - account that appeared in various church papers around 1895,

claiming major improvements in the character of the area, including a

Sunday evening congregation at the parish church of 500 - respectable working people: Rector Turner observed that out of a population of ten thousand, scarcely half a dozen families keep a domestic servant - plus many more connected to the simpler services of the mission churches, and the Sunday schools and bible classes.

In

addition,

- Details of all the

known pubs, inns, taverns and beer houses can be found here and here [two links to the same excellent site] or - with a list of all those in the civil district of St George-in-the-East - here

- The Vestry map

of 1878 shows the streets and alleys of St George-in-the-East local

government area (wider than the then-parish, as explained above) in detail.

- The fire insurance maps of Charles E. Goad

Ltd,

a London-based firm (but mapping many other parts of the country

too), originating in 1885 and updated until quite recent times, are an

invaluable resource because they are so detailed (on a scale of 1:480 -

1 inch to 40 feet), giving street numbers, the nature of premises (D =

dwelling, S = shop, PH = public house and so on) and names of many

businesses, as well as much information relevant for insurance

(such as construction materials - red = brick or stone, yellow =

wooden, light blue/purple = skylights; boilers; doors and shutters;

hydrants; fire alarm boxes; hydrants, and many dimensions - here is the

full key). The British Library website includes zoomable and printable

versions covering most of area covered by our parish and beyond, as detailed here,

running broadly from west to east:

Volume 5 (1887)

099 (St Katharine's Docks), 102 (Upper East Smithfield, and part of Docks), 103 (western end of St George Street & Pennington Street, and vaults), 104 (St George Street & Pennington Street west of Cannon Street Road

(including Denmark and Betts Street, and Prince's Square with the

Swedish chapel), 105 (St George Street & Pennington Street east of Cannon Street Road, including the church site)

119 (north of Royal Mint Street - part of Goodman's Field area), 120 (between Upper East Smithfield and Royal Mint Street, with railway and Peabody Buildings)

Volume 11 (1899)

338 (Gowers Walk to Batty Street, between Ellen Street and Commercial Road), 339 (William Street to Commercial Road), 340 [missing], 341 (Christian Street to Cannon Street Road, north of Cable Street), 342 [missing], 343 (Tait Street west of Anthony Street to Commercial Road), 344 (Tait Street east of Anthony Street to Commercial Road, as far as Watney Street), 345 (Cable Street, Chapman Street area up to Tait Street), 346 (Cable Street to Watney Street, including St George's Gardens &c)

|

- PortCities

London provides a wealth of information about all aspects of

the history of the Docks

- Gordon

Barnes Stepney

Churches (Ecclesiological Society / Faith Press 1967)

gives further background information

The East London History

Society

enables you to compare a range of old and new maps

side-by-side and has many other excellent features. Maps which it

does not feature include that of Weller in 1868 [right], which clearly shows the

location of the churches, and the 1894 Ordnance Survey map of part of the parish [far right].

The East London History

Society

enables you to compare a range of old and new maps

side-by-side and has many other excellent features. Maps which it

does not feature include that of Weller in 1868 [right], which clearly shows the

location of the churches, and the 1894 Ordnance Survey map of part of the parish [far right].- Here

are details of the clergy for 1860-1900.

After Bryan King's departure, patronage of the benefice passed to the

Bishop of London, to whom the Principal and Fellows of Brasenose

College transferred most of their East End patronage in return for

various country livings. In 1879 the Rector's stipend was increased by

£500 a year by the voidance of a City rectory, St Alphege London Wall.

The parish has never been regarded as an 'ecclesiastical prize', but

the Rector's stipend was now a comfortable £800 after deductions -

though from this they had to meet the expenses of assistant clergy and

other costs.

THE

TWENTIETH CENTURY

We

entered the new century with three churches - St George-in-the-East,

Christ Church Watney Street and St John-in-the-East Golding Street. All

were kept busy, with a full range of parish clubs, societies and

organisations, and buildings to match, including St George's Mission

House and the parish room behind the Rectory (see above), as well as St

Mathew Pell Street (now used as a parish hall) and Tait Street Mission

Room.

This interview with R.W. Harris

(Rector 1897-1903) in the Charles

Booth archive

[B222,

pages 150-179] details many of these parish organisations, and

reports

on the 'invalid kitchen', and the initiative of 'St

George-in-the-East Window Garden

Society' - a recognition that a windox box rather than a garden was the

closest many came to nature (see here for an 1865 initiative by the Royal Horticultural Society along these lines). In

1906 the winner of the annual

competition was the ten-year old Harry Sleight, who lived at 1 Redmead

Lane,

Wapping all his life until he was moved out by Docklands

redevelopment

in the late 1970s. He

was presented with an

inscribed silver pocket watch, which he treasured all his life, as does

his family - it is still in good working order (our thanks to his grandson Geoffrey for

these pictures).

This interview with R.W. Harris

(Rector 1897-1903) in the Charles

Booth archive

[B222,

pages 150-179] details many of these parish organisations, and

reports

on the 'invalid kitchen', and the initiative of 'St

George-in-the-East Window Garden

Society' - a recognition that a windox box rather than a garden was the

closest many came to nature (see here for an 1865 initiative by the Royal Horticultural Society along these lines). In

1906 the winner of the annual

competition was the ten-year old Harry Sleight, who lived at 1 Redmead

Lane,

Wapping all his life until he was moved out by Docklands

redevelopment

in the late 1970s. He

was presented with an

inscribed silver pocket watch, which he treasured all his life, as does

his family - it is still in good working order (our thanks to his grandson Geoffrey for

these pictures).

A high point in the time of F. St. J. Corbett

(Rector 1903-19) was the visit on 14 July 1904 of Queen Alexandra, wife

of King Edward VII, for a flower show and sale of work (the fourth

picture shows the Victorian extension to the Rectory), which provided a

welcome fillip to parish finances. The circumstances of her visit are

recounted in press cuttings here and an interview here.

A high point in the time of F. St. J. Corbett

(Rector 1903-19) was the visit on 14 July 1904 of Queen Alexandra, wife

of King Edward VII, for a flower show and sale of work (the fourth

picture shows the Victorian extension to the Rectory), which provided a

welcome fillip to parish finances. The circumstances of her visit are

recounted in press cuttings here and an interview here.

Services

at the parish church in this period were as follows:

Holy

Communion every

Sunday 8am & 12 noon, Greater Festivals also at 7am, Thursday

8.30am,

Saints' Days 10am

Matins

Sunday & Monday 11am, other days 10am Evensong Sunday

6.30pm, Weekdays 8pm (with sermon on Wednesdays)

Holy

Baptism Sunday 3.45pm & Wednesday 7.30pm

Churching

of Women

before or after any service Sunday School

10am & 3pm

|

Tait Street Mission remained active, with a men's meeting on

Sundays

at 4pm and a children's service at 8.30pm, as well as weekday

activities. There was a 'lady

worker', Miss Emily FitzHardinge Berkeley, living at the Rectory - more

details here. However,

despite a full round of activities here, at the parish church and St Mathew Pell Street, the parish was seriously struggling:

numerically (as the area became more Jewish in population),

financially, and pastorally. See the Rector's extremely

revealing confidential report

of 1914 to the Bishop of Stepney (plus the published accounts for

1915), which candidly sets out the difficulties. According to Mr

Corbett, the Bishop claimed not to be

aware of the extent of the lay team, or of the problems they faced.

And,

as was still common, the Rector had to pay the curate from his own

stipend; unlike his predecessor, he did not have a 'private' income.

Here

is a description of life in various parts of the parish in 1911.

The First World War and its aftermath

Then

came the Great War.

Clergy left to serve as chaplains on the

front, or, like our own Rector [pictured - more details here] remained in their parishes while serving units on the home front. They discovered (though

those who had served in the East

End surely knew already) how tenuous were the links of soldiers with

the Christian

faith: the church needed to change. (See