The Revd J.C. Pringle - some

parish magazine articles, 1923-25

Southern Africa

In 1923 Pringle spent a period in India with the Mission of Help, and

in July and September 1923 he

described his journey home, adding some forthright views criticising

policy over the 'Kenyan' [note his use of inverted commas] Asians,

who had originally been brought as

indentured labourers to build the Kenya-Uganda railway, and by 1920 had

become a sizeable and affluent mercantile group, with tensions riding

high until a 1927 political settlement. He then goes on to praise

Rhodesia. Pringle had previously been a colonial civil servant,

which is perhaps how he managed to arrange a meeting with Field Marshal

Jan Smuts,

who was Prime Minister of South Africa at the time - a reactionary in

terms of the apartheid regime, yet a prime mover in the creation of the

League of Nations. (Two generations earlier Marmaduke Hare, Vicar

of Christ Church Watney Street, had married the South African premier's

daughter.) The Portuguese fort of N. S. da Conceiçao,

Maputo (formerly Lourenço Marques) in Mozambique, which he

visited, is

now a World Heritage site; it is the oldest European building in the

southern hemisphere. Was Pringle aware that J.H. Bovill, a former

curate of

Christ Church Watney Street, has served here as consul and chaplain

from 1894-1901? Furthermore, in 1939 Stanley Andrews went from his

curacy at St

George's to serve there briefly as a Missions to Seamen chaplain.

[pictures added from other sources]

Instead

of coming home as I went out, through the Red Sea, I imitated

travellers to India before the opening of the Suez Canal and returned

via South Africa. There is a fortnightly service of steamers run by the

'B.I.' from Bombay to East African ports, and I sailed for Beira on the

s.s.

Taroba. The trip occupies 17 days. During a good part of it we

were steaming practically along the equator itself from the lonely and

little visited Seychelles islands, right in the middle of the Indian

Ocean, to Mombasa the seaport of British East Africa or 'Kenya'. Instead

of coming home as I went out, through the Red Sea, I imitated

travellers to India before the opening of the Suez Canal and returned

via South Africa. There is a fortnightly service of steamers run by the

'B.I.' from Bombay to East African ports, and I sailed for Beira on the

s.s.

Taroba. The trip occupies 17 days. During a good part of it we

were steaming practically along the equator itself from the lonely and

little visited Seychelles islands, right in the middle of the Indian

Ocean, to Mombasa the seaport of British East Africa or 'Kenya'. At

Mombasa we took on board several passengers from 'Kenya', and soon

shared their indignation at the crazy and criminal policy of the

British Government in proposing to give the Indians, who have come over

under British protection to make money out of the natives, the same

political rights as the British settlers. If it were not so serious a

matter for our people, the proposal would be absolutely laughable. The

Indians themselves say that all they want is to be allowed to trade

under British protection, knowing well that without it the Kaffirs

would kill them mercilessly whenever the fancy took them. A few of

Gandhi's agitators who make their living out of it have raised this

question in Whitehall. Our precious Parliamentarians who mistook these

rogues for 'India' and now mistake them for 'Kenya' are panting to sell

our settlers to them in East Africa!! And then we are surprised when

our colonies want to break from us. What else can they do? At

Mombasa we took on board several passengers from 'Kenya', and soon

shared their indignation at the crazy and criminal policy of the

British Government in proposing to give the Indians, who have come over

under British protection to make money out of the natives, the same

political rights as the British settlers. If it were not so serious a

matter for our people, the proposal would be absolutely laughable. The

Indians themselves say that all they want is to be allowed to trade

under British protection, knowing well that without it the Kaffirs

would kill them mercilessly whenever the fancy took them. A few of

Gandhi's agitators who make their living out of it have raised this

question in Whitehall. Our precious Parliamentarians who mistook these

rogues for 'India' and now mistake them for 'Kenya' are panting to sell

our settlers to them in East Africa!! And then we are surprised when

our colonies want to break from us. What else can they do? Then

we

came to Zanzibar and saw the sad spot where H.M.S.

Pegasus flew the

only white flag ever flown by the British Navy when shelled by the

German Cruiser, Könisberg. The officer commanding the Pegasus drew her

fires and started cleaning boilers in an unprotected roadstead!

Gandhi's little lot in Zanzibar sent the Germans the tip. They sent in

a launch in broad daylight, took the bearings of the Pegasus and

knocked her to pieces from the other side of the island! The commander

did not even order the crew to leave their helpless ship but flew a

white flag. Then

we

came to Zanzibar and saw the sad spot where H.M.S.

Pegasus flew the

only white flag ever flown by the British Navy when shelled by the

German Cruiser, Könisberg. The officer commanding the Pegasus drew her

fires and started cleaning boilers in an unprotected roadstead!

Gandhi's little lot in Zanzibar sent the Germans the tip. They sent in

a launch in broad daylight, took the bearings of the Pegasus and

knocked her to pieces from the other side of the island! The commander

did not even order the crew to leave their helpless ship but flew a

white flag. Next,

at Mozambique we went ashore and had a look at the

grim fort which has frowned there for 400 years, ever since the days of

Portuguese greatness. It is a dead alive little place and frightfully

hot. Hardly anything happens at all except the work of a station of the

Eastern Telegraph Co. Next,

at Mozambique we went ashore and had a look at the

grim fort which has frowned there for 400 years, ever since the days of

Portuguese greatness. It is a dead alive little place and frightfully

hot. Hardly anything happens at all except the work of a station of the

Eastern Telegraph Co.At last I reached my port of landing, Beira; left the pleasant company on the s.s. Taroba, and went ashore to see that quaint spectacle, a port where every atom of trade and business is British, but the place is owned, taxed and mis-managed by the Portuguese. Another thing that struck me all up that coast was the beautiful, newly-painted steamers of the French and Germans blazing with light and offering fast passages to Europe, while the British vessels looked war-worn and rusty to a degree. The French and Germans cannot pay their debts but they have plenty of money to subsidise steamers to carry British goods and passengers to British colonies. The green and gold paint on a big German steamer in Beira was wonderful to behold.  When

once I left Beira, and its heat and wet and mosquitoes behind, I became

acquainted with one of the greatest achievements of British enterprise

in modern times, the Rhodesian Railways. We can, most of us, well

remember when Stanley went up the Congo to look for Livingstone [ed: this meeting occurred in 1871],

when Dr Jameson started from Kimberley in a Cape cart to go up to what

was to be Rhodesia - but no one expected to see him come back again:

how later on he made his way into Beira in a shirt and one slipper

across the deadly 'fly' country and the Pungwé flats, after being given

up for dead. It all seems yesterday! Now they serve you a five course

dinner on the restaurant car as you cross the Pungwé flats and the

'fly' country, make down your bed at night and call you with coffee in

the morning. When you have travelled 950 mailes over that vast green

silent expanse, you find yourself at the Victoria Falls.

'Livingstone' now means a little town close by across the Zambesi

lit with electric light, and your fellow passengers say they are going

on to the Congo 900 miles further on, just as we might talk of going to

Torquay! How easy to write these figures! What a long drawn out heroic

struggle they represent! I forget how many lives per mile that line has

cost. A cousin of mine made the first road over part of the route. The

blacks he met had never before seen a horse or a white man. He died,

like the rest, of black water fever. When

once I left Beira, and its heat and wet and mosquitoes behind, I became

acquainted with one of the greatest achievements of British enterprise

in modern times, the Rhodesian Railways. We can, most of us, well

remember when Stanley went up the Congo to look for Livingstone [ed: this meeting occurred in 1871],

when Dr Jameson started from Kimberley in a Cape cart to go up to what

was to be Rhodesia - but no one expected to see him come back again:

how later on he made his way into Beira in a shirt and one slipper

across the deadly 'fly' country and the Pungwé flats, after being given

up for dead. It all seems yesterday! Now they serve you a five course

dinner on the restaurant car as you cross the Pungwé flats and the

'fly' country, make down your bed at night and call you with coffee in

the morning. When you have travelled 950 mailes over that vast green

silent expanse, you find yourself at the Victoria Falls.

'Livingstone' now means a little town close by across the Zambesi

lit with electric light, and your fellow passengers say they are going

on to the Congo 900 miles further on, just as we might talk of going to

Torquay! How easy to write these figures! What a long drawn out heroic

struggle they represent! I forget how many lives per mile that line has

cost. A cousin of mine made the first road over part of the route. The

blacks he met had never before seen a horse or a white man. He died,

like the rest, of black water fever. When

Livingstone first discovered the Victoria Falls the natives, naturally

enough, regarded them as an abode of devils. To-day a beautiful little

white span of a bridge carries the train across 400 feet above the

'boiling pot' below the Falls. To climb down to the bottom and sit by

those raging waters is a bit of an experience. We cannot sit close by

the sea in a great storm, at least not comfortably! When that vast mass

of Zambesi water has crashed down its 400 feet, it behaves as though it

had gone raving mad: and angry at that. It rushes backwards and forward

on the top and underneath like a maniac. Similarly if you stand by the

edge, up above, as darkness comes on, while the waters tumble into that

awful cavern full of foam and spray and mist and noise, it does indeed

seem like an abode of devils. One is glad to run away. When

Livingstone first discovered the Victoria Falls the natives, naturally

enough, regarded them as an abode of devils. To-day a beautiful little

white span of a bridge carries the train across 400 feet above the

'boiling pot' below the Falls. To climb down to the bottom and sit by

those raging waters is a bit of an experience. We cannot sit close by

the sea in a great storm, at least not comfortably! When that vast mass

of Zambesi water has crashed down its 400 feet, it behaves as though it

had gone raving mad: and angry at that. It rushes backwards and forward

on the top and underneath like a maniac. Similarly if you stand by the

edge, up above, as darkness comes on, while the waters tumble into that

awful cavern full of foam and spray and mist and noise, it does indeed

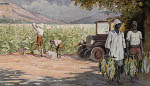

seem like an abode of devils. One is glad to run away. Rhodesia

I thought an excellent country

offering a splendid future for

Englishmen. Things grow magnificently there and one day our best meat,

grain, fruit, jam preserves and

tobacco will come from there. What is

wanted now is a public to buy

the stuff. Instead of pouring our money

by the million into the laps of rich Americans let us smoke Rhodesian

tobacco and cigarettes, - quite as good as American and no

dearer, - and thus kill two birds with one stone, do a good turn to our

own people in Rhodesia, and bring the dollar down to its pre-war

exchange, and take a load off Mr. Baldwin's mind. But you ought to see

the flowers in the Rhodesian gardens! Rhodesia

I thought an excellent country

offering a splendid future for

Englishmen. Things grow magnificently there and one day our best meat,

grain, fruit, jam preserves and

tobacco will come from there. What is

wanted now is a public to buy

the stuff. Instead of pouring our money

by the million into the laps of rich Americans let us smoke Rhodesian

tobacco and cigarettes, - quite as good as American and no

dearer, - and thus kill two birds with one stone, do a good turn to our

own people in Rhodesia, and bring the dollar down to its pre-war

exchange, and take a load off Mr. Baldwin's mind. But you ought to see

the flowers in the Rhodesian gardens![compare the later 'baccy parson' of St Paul Dock Street...] Five more days and nights in a very comfortable train, a trip down 1,200 feet in a Transvaal gold mine, a scramble up Table Mount, lunch and tea and a pleasant chat with "Jammy" Smuts at Parliament House in Cape Town, and once again at sea. The P.P. s.s. 'Berrima' brought me in perfect comfort 6,000 miles, from Cape Town to Tilbury in 3 weeks all but 5 hours for the sum of £21! That is what competition does for the travelling public, and, reader, please taken note of it! |

preoccupied

some Anglicans in the 1920s. Back in 1906, a Royal Commisssion had

declared the 1662 Book of Common Prayer 'too narrow' to meet the

worshipping needs of the Church of England - and the experience of

wartime chaplains had certainly confirmed this. The background

was a long period of growing diversity, mainly in Anglo-Catholic

parishes, in the use of unauthorised (including Roman Catholic) texts,

which the 1874 Public Worship Regulation Act had sought but failed to

control. It should be noted that St George-in-the-East, despite

the Ritualism Riots

here, had always stuck to the texts and ethos of the BCP.

Finally, in the 1920s, various groups put forward proposals for change,

but in 1927 and again in 1928 Parliament rejected the 'Deposited Book',

to which Evangelicals were opposed - though its provisions were to be

widely used anyway. The story is well-charted by Donald Gray in The 1927-28

Prayer Book Crisis (Joint Liturgical Studies 60 &

61, Alcuin Club/GROW 2005 & 2006).

preoccupied

some Anglicans in the 1920s. Back in 1906, a Royal Commisssion had

declared the 1662 Book of Common Prayer 'too narrow' to meet the

worshipping needs of the Church of England - and the experience of

wartime chaplains had certainly confirmed this. The background

was a long period of growing diversity, mainly in Anglo-Catholic

parishes, in the use of unauthorised (including Roman Catholic) texts,

which the 1874 Public Worship Regulation Act had sought but failed to

control. It should be noted that St George-in-the-East, despite

the Ritualism Riots

here, had always stuck to the texts and ethos of the BCP.

Finally, in the 1920s, various groups put forward proposals for change,

but in 1927 and again in 1928 Parliament rejected the 'Deposited Book',

to which Evangelicals were opposed - though its provisions were to be

widely used anyway. The story is well-charted by Donald Gray in The 1927-28

Prayer Book Crisis (Joint Liturgical Studies 60 &

61, Alcuin Club/GROW 2005 & 2006).| Speaking

generally, the present book may be called the ninth we have had - (1)

pre-Augustine (2) Augustine, (3) Osmund 1078, (4) Bishop Poore 1217,

(5)

Cranmer 1549, (6) 1552, (7) 1559, (8) 1604, (9) 1661 - as varied by the

1871 table

of lessons. Prayer Books closely resembling ours though differing

in

important particulars are those of the Scottish Church (latest revision

1912), the American Church (revised in 1892), the Irish Church (revised

in 1877), and the South African Church (revision later than 1912). We are rather surprised at first to find that practically all the proposals are for a return to more ancient forms of service, but when we look into it our surprise disappears, for we perceive that all the finest material in our services comes from the golden age of the Church, the days of Chrysostom, Jerome, Basil, Ambrose, Gregory, and the like. This discovery is by no means confined to the Church of England. Thus the Congregationalists, in their Prayer Book drawn up in 1920, borrow largely from these writers, as do the Scottish Presbyterians.... |

| ...There seems but little prospect of a return to commercial prosperity within twelve months, though it may come as unexpectedly as the present depression. One of the most remarkable incidents in this strange epoch of ours was the way in which the most experienced business men were taken unawares by the great 'slump'. Confidence is a most mysterious thing. It has often spread through the trading community with great swiftness bringing in its train employment for nearly everybody. The history of the past two centuries teaches us that this may happen again; within ten years of Waterloo there was a huge boom in trade; and things move much more rapidly today than they did a century ago.... |

| May 1924 Although there is a very great amount of brave and splendid work being done by Missionaries in most parts of the world, there is also a good deal of criticism. This generally takes the form of the question, "Why should you go and interfere with another man's religion?" "Are you so good yourself that you have any right to go and preach to anyone else?" "Are things so satisfactory in England that we have much to tell the Indians, Chinese, Africans, or even the Cannibal Islanders?" It is part of the system of politics in vogue in this country that numbers of people should earn their living and climb up in the world by abusing the conditions of life in this country. They do so in the hope that they or their friends will be given the job - at £5,000 a year and pickings - of putting it right. Millions of our fellow-countrymen go about wondering why they are fated to live in such a horrible country! I have seen the tears come into a man's eyes at a public meeting when he thought, and spoke, about the abominable state of affairs in this country. This is very amusing to anyone who has lived abroad, especially in the East for any length of time. If one of these speakers could find himself living on the food, in the clothes, houses, towns, villages and climate of any part of Asia or North or Central Africa, he would experience a very severe shock indeed, and we should have to listen to very long speeches on the comfort, freedom and safety of old England for many a day afterwards. There is no single detail in which a comparison of the conditions of life would not be laughable. If readers liked parallel pictures of the conditions of life in several parts of Asia and Africa these could be supplied, but at the moment the subject is Foreign Missions. A missionary goes among a people to whom he is a stranger in appearance, language and tradition. They hate all such. He comes for the very purpose of interfering with their superstitions and customs and changing their ideas. They hate and FEAR any such interference. He comes as a poor man living in humble style (while most people from great western countries present a substantial if not imposing appearance), unarmed, unsupported by power or force. The government and police highly disapprove of him, and are not at all inclined to protect him if the people desire to torture or kill him. It is easy to see that far more courage is required to be a missionary than to follow any other occupation in the world. Furthermore this courage has in most cases to be displayed in tropical climates where one nearly always feels tired, depressed, exhausted, seedy, and where diseases unknown in England, cholera, spru (chronic dysentry), all forms of malaria, smallpox and leprosy are constantly present. Does anyone honestly believe that people will go on facing such a life unless it was patently obvious that they had something of enormous value to tell and give the strange people to whom they have gone? Christianity even in the imperfect form of which we are capable and worthy in Europe today is immeasurably superior to the beliefs and customs of any Africans and Asiatics, except the handful of highly educated ones, and far the best ideas in their heads come from Christianity although they do not admit it. An educated Indian, Chinese or Japanese will begin by telling you he is not a Christian, and will then go on to give you his religious ideas. You will be surprised at first to notice how like they are to your own. Lots of sayings current at home, such as, "All religions are much the same," "It does not matter what a man believes if he does what is right," etc., come back to you, and you wonder if they are right! You soon find out your mistake! The man knows nothing about the religion of his own people, and does not want to know anything. He is handing out to you ideas from western books, themselves the outcome of nearly 1900 years of Christianity! You are told that it is unnecessary to send missionaries to people who have such fine ideas, but you are not told where they got these ideas from, - the New Testament! Don't forget, then, dear reader, to go to the Missionary Exhibition and to support it in every way..... June 1924 Why not slip over to Mile End and see it for yourself before it is over? It is not very far, - a penny ride from the top of New Road. You ask "what is the object of it?" I may perhaps admit that missionaries are courageous, even heroic people, and do much good, but what can the exhibition tell me about them?" The aim of the exhibition is to make real to us the enormous difference between the lives of the people to whom the missionaries go and our own lives. If you retort that an exhibition can only do a very little to make the difference real you are perfectly right; and the promoters of this exhibition have been imploring us for twelve months to read books and form study circles about the countries and people to whom the missionaries go, so that, when we saw the exhibition, we should be able to understand all there was behind the exhibits we saw. We look at a representation of a hut, even a village, at the furniture, if any, utensils, clothes, ornaments, and perhaps objects of worship, of a strange people. We are inclined to say "well, if he likes those kinds of things, let him have them: they suit him: they don't hurt me." We do not stop to ask what kind of chance of and independent existence for the individual - especially a woman - that kind of life gives. We all believe, in the West, that every person has a character, an individuality, a soul, separate from all others, and of equal importance, or value, in the sight of God, to any other. To give that soul a chance of growing to what God meant it to be, should be the object of social and political institutions. That is the Christian idea, and it has been worked out and made real, in England, in a very large measure. It has not begun to be thought about at all in all the countries to which most of our missionaries go; and even where from time to time the ideal has been known, and in a small measure realised, as in Japan and here and there in India and China, the forces operating against any such ideal, and causing the individual to be submerged in the mass, are tremendous. But this submerging is accompanied by a callous brutal tyranny and oppression, and utter indifference to the welfare or feelings of the weak, especially of the female sex. Even under the British administration in the days of its strength and vigour, and when its officers were keen and enthusiastic Englishmen, the life of a woman counted for nothing in India, and, if her life, how much less her honour, her character, her happiness. And that was true not because our men were not passionately desirous of giving British justice and protection to all alike, but because native opinion accounted women so cheap that their lives could be taken without whisper coming out beyond the high walls of the rambling premises housing the Hindu family with its numerous branches. In a poem recited in numberless schools on Empire Day many of the peoples included in the Empire are referred to as "half devil, half child." This is a very true and valuable definition. It is the phrase of a great thinker and keen observer who has travelled the Empire many times from end to end; and it is sufficient in itself to give the purpose of missionary effort, and to describe its difficulties. Our faith is that God meant his creatures to grow up, slowly and painfully no doubt, to "the measure and stature of the fulness of Christ", and NOT to remain "half devil, half child." What a magnificent enterprise. I cannot believe you will remain cold to it, once you interest yourself in it .... |

| January

1925: Change of Rector Readers probably know that Mrs. Pringle has had very bad health ever since she came to St. George's, and has had one very serious operation in that time. The consultant whom she has been under for three years has had an X-ray examination made and declares emphatically that she must live henceforth in the quietest possible surroundings and must never again attempt to live in a Rectory or Vicarage. She has gone to the South of France, and the Bishop has given the Rector leave to join her for five weeks in the new year. At the same time the Rector had no choice but to send in his resignation of St. George's to the Bishop of London. This takes effect on March 25th. The Rector has done so with the utmost regret. He is very sorry indeed to leave our beautiful church, our historic and interesting parish, and the kind friends whom he values so much and to whom he owes so much. It is understood that the Bishop of London had appointed the Rev. C.J. Beresford, of the S.P.C.K. College, Commercial Road, to St. George's, provided no valid objection is urged when the living is put into sequestration after the resignation of the present Rector. We are confident that this will be an extremely popular appointment. Mr. Beresford is one of the best known figures in Church life in Stepney, and apart from his many other admirable qualities his music will prove an invaluable asset to St. George's. We desire also to bid Godspeed to his colleague, our friend Mr. Ward, who goes to be Curate at St. Pancras Parish Church. [He was a colleague of Beresford at the SPCK College, and like Beresford had often led worship here during the Rector's absence.] February 1925: The Rector Now that we are recovering from the first effect of the shock of the news of the Rector's forthcoming departure, many of us will begin to realise what our loss will be, as besides being Rector he is something more to many of us, viz., a personal friend of whom it can be truly said, it is a privilege to know him, and perhaps it will only be from that angle, we shall feel our loss the most. Only those who know him intimately can appreciate his anxieties, both for the spiritual and material welfare of his parish, the members of which he does not confine to the limits of our own Church, but embraces all denominations and Creeds. A striking example of which was seen at the recent unveiling of the War Memorial in the presence of representatives of different denominations [ed: and faiths - there were also Jewish representatives present] - surely a striking testimony to the broad-mindedness and tolerance of the Church. The writer has knowledge of many acts of personal kindnesses, both by Mrs. Pringle and the Rector, which have endeared them to w wide circle not wholly confined to the Church. (Contributed). April 1925: Letter from the Rector My dear Friends, I write a few lines to thank you for all the kindness and forbearance you have shown me during my six years term of duty in this parish. I have been in many ways an unsatisfactory Rector to you, partly because of my personal failings, and partly because the method of work enjoined upon me by the Bishop of Stepney, the Archdeacon of London and the Rural Dean, when I was invited to come here, entailed such a busy life, and occupied so fully every hour of every day, that it has been impossible for me to see as much of you personally as I should have liked. Our Master ordered us not to fail to give "a cup of cold water to the least of these little ones." To obey that command in an area like this and a town like London means taking an active part in the work at least of the main agencies for assistance and betterment which are active in the area. This I have endeavoured to do; and through the Bishop I have been given as colleagues several experienced and specially trained and qualified lady workers. It was his opinion that while the size of our congregation did not justify the appointment of an assistant curate, the forms of Christian service he wanted undertaken here are far better rendered by trained lady workers than by any curate likely to be available. These arrangements should perhaps have been more fully explained, and I may have been to blame in not explaining them earlier. I imagined, perhaps erroneously, that they were well known. One of the greatest and strongest traditions of the Church throughout the ages has been her attempt to carry our her Master's command to succour the distressed and to care for the children. It is only the complicated machinery for doing so which has developed in this great city that prevents the most casual observer from perceiving at once that the most direct and obvious way of obeying Christ's express commands is to assist as far as possible in this work. Perhaps a word or two about my sermons may be permissible. I am quite aware that they have pleased no one: interested very few; and, for the most part, simply not listened to. For this I am sorry, not on my own account, but for the sake of the subject. My aim has been very simple, viz.: to place before you the contents of our Bible, and the history of our Faith and Church, in such a way as to interest and delight you; and my hope has been to increase your love of all three. I have not spared time and trouble, but I quite recognise that more than that is required for success. In that I have failed to do my Master's work successfully in this place, I am very sorry and I tender you, and Him, my humble apology, but it has always been a pride and delight to me to serve Him in the beautiful building Nicholas Hawksmoor raised for His glory on this spot. It is of course a very small matter that my preaching has been a failure. The English have never cared much either to make or to listen to speeches and it is certainly not God's purpose that they should be saved by them. What is, I firmly believe, a great thing is voluntary co-operation to render service to God. A church can perform no greater service than to be a centre of such. Mrs. Pringle joins me in the desire to express our heartfelt gratitude to all those who have given and are giving their services here. [He then lists his thanks to many people for their specific services.] My resignation takes effect on March 25th but, by law, the living must be in the hands of sequestrators for four weeks before the resignation of the outgoing Rector and the institution of the incoming one. The sequestrators are the churchwardens, They have asked me to be responsible for the services up to Low Sunday, April 19th. The institution and induction of the Rev. C.J. Beresford by the Bishop of Stepney and the Archdeacon of London respectively will take place at 4.0p.m. on Saturday April 25th. |

Back to History page | Back to Clergy 1900-