Christ Church Watney Street (1841 – 1951)

WHAT A LONDON CURATE CAN DO IF HE TRIES

Three

of the sons of William Quekett, the master of Langport grammar school

in Somerset from 1790-1842, achieved a measure of fame: Edwin John and

John Thomas Quekett, as histologists and microscopists, and their older brother

William Quekett

(1802-88). He had studied at St John's College Cambridge,

reading as widely as possible (he attended lectures on fen drainage),

and was ordained in 1825, serving at South Cadbury, in the diocese of

Bath

and Wells. He was by conviction an Evangelical. Four years later a

friend told him there was a post as curate and Lecturer at St

George's. He came for interview, only to discover, as his cab drove on, that it was not St

George Hanover Square, as he had thought, but the more challenging

situation of St George-in-the-East. [This is a recurring error: various

websites implausibly claim that Edward William Spencer Cavendish, 10th

Duke of Devonshire (1895-1950), was born in this parish despite the

family's links being with the other church.] To his credit, he stayed

anyway,

and achieved great things in his 24 years here (curate 1830-41,

incumbent of Christ Church 1841-54). He was applauded in

Charles Dickens' Household

Words (16 November 1850) in an

article 'What a London curate can do – if he tries' which you can read here. It

includes an account of the curious circumstances of his appointment.

Three

of the sons of William Quekett, the master of Langport grammar school

in Somerset from 1790-1842, achieved a measure of fame: Edwin John and

John Thomas Quekett, as histologists and microscopists, and their older brother

William Quekett

(1802-88). He had studied at St John's College Cambridge,

reading as widely as possible (he attended lectures on fen drainage),

and was ordained in 1825, serving at South Cadbury, in the diocese of

Bath

and Wells. He was by conviction an Evangelical. Four years later a

friend told him there was a post as curate and Lecturer at St

George's. He came for interview, only to discover, as his cab drove on, that it was not St

George Hanover Square, as he had thought, but the more challenging

situation of St George-in-the-East. [This is a recurring error: various

websites implausibly claim that Edward William Spencer Cavendish, 10th

Duke of Devonshire (1895-1950), was born in this parish despite the

family's links being with the other church.] To his credit, he stayed

anyway,

and achieved great things in his 24 years here (curate 1830-41,

incumbent of Christ Church 1841-54). He was applauded in

Charles Dickens' Household

Words (16 November 1850) in an

article 'What a London curate can do – if he tries' which you can read here. It

includes an account of the curious circumstances of his appointment.

The

elderly Rector, Dr Farington, in post since 1802, was unsupportive of

Quekett's efforts, being content to leave

the parish as he found it rather than tackle its huge social

problems. Quekett's first project was to fit out as boys,

girls and infants schools three

arches

east of Cannon Street Road under the

viaduct of the new London and Blackwall Railway: further details here.

Building

a new church in the parish had been mooted in 1831

by the Church Building Commissioners, and by the Bishop of London in

1837 (who hoped for three others in Stepney), but all depended on local

initiative, and the Rector argued that church rate had to be spent on

the newly-purchased extension to the burial ground and on church restoration, so no

funds were available. But in

1838 a local builder, George Bridger, offered the CBC the sites of

three houses in Watney Street, which he held on lease from the

Mercers' Company. He was willing to make a gift of these leaseholds,

valued at £1,130, paying the Mercers £350 for the

freehold, and compensation of £35 to the tenants, on three

conditions:

-

it

should designed by John Shaw junior

- it

should be built by himself, and

- there

should be no burial ground.

The

CBC agreed; the site was conveyed to them on 27 March 1839. A

foundation stone was laid on 11 March 1840, and Messrs George &

James Weddell Bridger, of Aldgate Street, built the church, which was

consecrated on 3 May 1841, with 1200 sittings. The total cost to the

CBC was £7,251 9s. 11d. including the site (which in the

event

they rather than Bridger bought). In 1845 two adjacent houses were

adapted to provide a vicarage, adding a hall and four large

rooms at a cost of £1,400; Quekett's

children laid

the foundation stone (his wife Harriet [left] died in 1849, aged 37). He had

previously lived at 51 Wellclose

Square - with his scientist brothers at number 50.

The

CBC agreed; the site was conveyed to them on 27 March 1839. A

foundation stone was laid on 11 March 1840, and Messrs George &

James Weddell Bridger, of Aldgate Street, built the church, which was

consecrated on 3 May 1841, with 1200 sittings. The total cost to the

CBC was £7,251 9s. 11d. including the site (which in the

event

they rather than Bridger bought). In 1845 two adjacent houses were

adapted to provide a vicarage, adding a hall and four large

rooms at a cost of £1,400; Quekett's

children laid

the foundation stone (his wife Harriet [left] died in 1849, aged 37). He had

previously lived at 51 Wellclose

Square - with his scientist brothers at number 50.

Although

he had built the church and was presented to the living, pew rents were

the only source of income, so for a while he retained his post at St

George's, working both churches with a fellow-curate John Sanders, until the death of

Dr Farington and the installation of Bryan King, after which he was

formally installed. He

set to work to raise £350 for fixtures, fittings

and a heating system. He bought an organ, insuring his life for

£100

as security for the balance - handbill right.

Although

he had built the church and was presented to the living, pew rents were

the only source of income, so for a while he retained his post at St

George's, working both churches with a fellow-curate John Sanders, until the death of

Dr Farington and the installation of Bryan King, after which he was

formally installed. He

set to work to raise £350 for fixtures, fittings

and a heating system. He bought an organ, insuring his life for

£100

as security for the balance - handbill right.

The Era announced on 31 October 1841 a magnificent organ, from the factory of Messrs. Gray and Davison, New-road, was opened last week at Christ Church, St.-George's-in-the-East, by Mr. Thomas Adams, in the presence of upwards of 2000 persons ... In December 1841 it announced (though mis-naming the church as 'St George-in-the-Fields') that Edward Cruse (b.1807) had been appointed organist. He had already published well-reviewed psalm chants and settings, and went on to produce other liturgical music, and to serve at the ritualistic church of St Barnabas Pimlico, whose current organist David Aprahamian Liddle is working on a biography of his predecessors, and has kindly provided us with information about Cruse. His successor two years later was the young prodigy William Rae (1827-1903) - see ch 7 here - appointed at the age of sixteen, an enthusiast for the music of Mendelssohn (whose oratorio St Paul was performed at the church). He was a pupil of William Sterndale Bennett, and, after a period at St Andrew Undershaft, went on to study in Leipzig and Prague. From 1860 he became became a key figure in the musical life of Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Quekett borrowed communion plate; but on Christmas Day 1843 a cab drew up at his house, leaving a box containing an anonymous gift of silver vessels. The paten was engraved A QUIBUSDAM EXTERNIS QUI NOMINARI NOLUNT - 'from certain outsiders who do not wish to be named'. (Sadly they were stolen in 1890.)

In 1847 he contributed to a survey carried out by the Statistical Society of London (founded in 1834, now the Royal Statistical Society)

which detailed housing conditions, rents and wages. Batty's Gardens,

between Backchurch Lane and Berners [now Henriques] Street was

described thus: Many of the houses

in this street have no back premises, neither light nor ventilation

from behind, and consequently are close, damp and unhealthy ... at one

corner of the narrow part is a dust heap on which is thrown night-soil

and refuse of every description, which saturates and penetrates through

the walls to the premises behind, creating a most disgusting nuisance

to the tenants... Its 'solution' to the area's problems was ... since

the population is, to some extent, the drainage from the grades next

above them, we should rather hope to find a cure by cutting off the

supply of degradation than by attempting to reform and elevate it in

the lowest depths to which it can sink. Quekett, however, had other ideas.

The

1851 census showed the population of the

parish

to be 12,497, in 1,664 households - an average per 'house' (in

some cases, a single room) of 7.51 (in two Whitechapel parishes, the

average was over 9 per household). Quekett, however, gave higher

figures: a population of 17,124 in 2618 households, across 77 streets

and courts, with 50 brothels, 21 pubs and 22 beer shops. The district, he said,

covered 63 acres; the average rent of a house was low, at

£8.10s. a

year.

Many other

projects followed:

Quekett

took up the cause of 'distressed needlewomen' - exploited pieceworkers,

single women with and without children, for whom job opportunities were

very limited (see some statistics here) - and saw assisted emigration to the colonies, to address

the inbalance of men there, as a solution (as did Charles Dickens);

together with Sidney Herbert MP he founded the Female

Emigration Society

in 1849; he served on the committee, as did W.W. Champneys, the Rector

of Whitechapel, and another local priest, the Revd B.C. Sangar.

A fellow-enthusiast was the Hon. Mrs Jane Stuart-Wortley [right],

wife of the

Recorder of London (son of Lord Wharncliffe, and an MP, unexpectedly

appointed to this post in 1851); she maintained a keen interest in

Christ

Church until her death in 1900, and writes here

about 'emigration work'. She paid for a nurse for the sick-poor in the parish, and was one of the founders of the East

London Nursing Society, set up in 1868 in the wake of the

cholera epidemic. The charity continues, with one of our

congregation a trustee.

Quekett

took up the cause of 'distressed needlewomen' - exploited pieceworkers,

single women with and without children, for whom job opportunities were

very limited (see some statistics here) - and saw assisted emigration to the colonies, to address

the inbalance of men there, as a solution (as did Charles Dickens);

together with Sidney Herbert MP he founded the Female

Emigration Society

in 1849; he served on the committee, as did W.W. Champneys, the Rector

of Whitechapel, and another local priest, the Revd B.C. Sangar.

A fellow-enthusiast was the Hon. Mrs Jane Stuart-Wortley [right],

wife of the

Recorder of London (son of Lord Wharncliffe, and an MP, unexpectedly

appointed to this post in 1851); she maintained a keen interest in

Christ

Church until her death in 1900, and writes here

about 'emigration work'. She paid for a nurse for the sick-poor in the parish, and was one of the founders of the East

London Nursing Society, set up in 1868 in the wake of the

cholera epidemic. The charity continues, with one of our

congregation a trustee. In

1851 he was

consulted by the incumbent of Holy Trinity, Minories over a mummified

head, found in its vaults (preserved in tannin-impregnated

sawdust); he said It

looked just like a New Zealand chief's head of which I had seen a

great many. The countenance expressed great agony; the eyes, the

teeth, the beard were perfect; and at the back of the head a very

deep cut was visible above the one that separated the head from the

body. He

referred it to Lord Dartmouth, whose family was responsible for the

church, and who claimed it was that of a family member who had

survived the first blow of the executioner's axe - but the legend that

it was the head of the Duke of Suffolk came later. (Holy Trinity closed

in 1899 and was joined to St Botolph Aldgate, where the head was buried

some time after the Second World War.)

In

1851 he was

consulted by the incumbent of Holy Trinity, Minories over a mummified

head, found in its vaults (preserved in tannin-impregnated

sawdust); he said It

looked just like a New Zealand chief's head of which I had seen a

great many. The countenance expressed great agony; the eyes, the

teeth, the beard were perfect; and at the back of the head a very

deep cut was visible above the one that separated the head from the

body. He

referred it to Lord Dartmouth, whose family was responsible for the

church, and who claimed it was that of a family member who had

survived the first blow of the executioner's axe - but the legend that

it was the head of the Duke of Suffolk came later. (Holy Trinity closed

in 1899 and was joined to St Botolph Aldgate, where the head was buried

some time after the Second World War.)

When Quekett left in 1854, the parish was served by a curate, two scripture readers and fourteen district visitors. The Sunday School had 25 teachers. He was rewarded, on the nomination of Lord Aberdeen, with the rich living of Warrington, whose previous rector, the Hon. Horatio Powys, has been made Bishop of Sodor and Man. By strange coincidence, Robert Farington's father had been Rector here 80 years previously, and the one book Quekett was given from Farington's library was a copy of his father's Warrington sermons. There, at St Elphin's, he built what was then the tallest spire in the north-west at 281 feet. He died in office, on Good Friday, 34 years later.

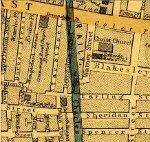

You can read some extracts from his gossipy autobiography My Sayings and Doings and a Reminiscence of My Life (Kegan Paul, Trench 1888) here (with links to further passages on particular topics). One final oddity about Quekett, which his book does not mention, is that in 1833 he had been appointed as the last rector of Goose Bradon, a sinecure parish in Hambridge (it was an abandoned medieval village with neither populuation nor a church) in his former diocese of Bath and Wells. Was this purely honorific, or did it produce a stipend? How did he square this with his opposition to lazy absentee clergy? Right is the Vestry map of 1878 showing the location of church and vicarage, and part of its parish.

Right is the Vestry map of 1878 showing the location of church and vicarage, and part of its parish.THE CHURCH BUILDING

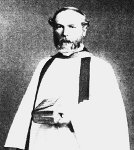

John

Shaw junior (1803-70) - left - was the son of John Shaw

(1776-1832) who had

been articled to George Gwilt the

Elder, and was the architect of St Dunstan

Fleet Street - see here

for details of links between the Gwilt and Shaw families, and that of

Dr Mayo, Rector of St George-in-the-East in the latter part of the 18th

century. Shaw junior had worked on Christ's Hospital. Christ

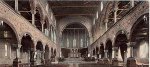

Church was in the 'Lombardic' Romanesque (or 'Round') style, in grey

bricks with

stone

dressings, with slated pyramid spires on the two west end towers.

Inside, he addressed one of chief chief architectural problems of the

age – providing maximum seating without ugly wooden galleries

–

by creating in the nave an arcade of two tiers of round-headed

arches, the upper one like a triforium containing the galleries, with

a clearstorey above (a solution that can be found elsewhere).

John

Shaw junior (1803-70) - left - was the son of John Shaw

(1776-1832) who had

been articled to George Gwilt the

Elder, and was the architect of St Dunstan

Fleet Street - see here

for details of links between the Gwilt and Shaw families, and that of

Dr Mayo, Rector of St George-in-the-East in the latter part of the 18th

century. Shaw junior had worked on Christ's Hospital. Christ

Church was in the 'Lombardic' Romanesque (or 'Round') style, in grey

bricks with

stone

dressings, with slated pyramid spires on the two west end towers.

Inside, he addressed one of chief chief architectural problems of the

age – providing maximum seating without ugly wooden galleries

–

by creating in the nave an arcade of two tiers of round-headed

arches, the upper one like a triforium containing the galleries, with

a clearstorey above (a solution that can be found elsewhere).

In

a letter to Bishop Blomfield about a new church in Bethnal Green, John

Shaw argued that the Romanesque (rather than the Gothic) option contains

in an eniment degree the qualities now so important. These appear to

be, first, economy; secondly, facility of execution; thirdly, strict

simplicity combined with high capability of ornament; fourthly,

durability; fifthly, beauty (quoted in Kathleen

Curran The Romanesque Revival:

Religion, Politics and Transnational Exchange, Penn State

Press 2003, p206). The

undisguised brick and iron columns of Christ Church were an example of

this. However, another view was that this was a building of startling ugliness, with cast-iron pillars and Norman arches of grimy brick.

In

a letter to Bishop Blomfield about a new church in Bethnal Green, John

Shaw argued that the Romanesque (rather than the Gothic) option contains

in an eniment degree the qualities now so important. These appear to

be, first, economy; secondly, facility of execution; thirdly, strict

simplicity combined with high capability of ornament; fourthly,

durability; fifthly, beauty (quoted in Kathleen

Curran The Romanesque Revival:

Religion, Politics and Transnational Exchange, Penn State

Press 2003, p206). The

undisguised brick and iron columns of Christ Church were an example of

this. However, another view was that this was a building of startling ugliness, with cast-iron pillars and Norman arches of grimy brick.

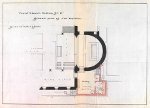

Originally,

the altar, surrounded by rails, stood against the east wall (behind

which was the only vestry). But in 1870 the architect James Brookes (1825-1901) opened a

round-headed arch in the east wall to add a large apsidal chancel. He

formed a choir in the first bay of the nave, and designed a

decorative scheme which was completed by 1885 [1870 plan, ICBS 07172, left].

Originally,

the altar, surrounded by rails, stood against the east wall (behind

which was the only vestry). But in 1870 the architect James Brookes (1825-1901) opened a

round-headed arch in the east wall to add a large apsidal chancel. He

formed a choir in the first bay of the nave, and designed a

decorative scheme which was completed by 1885 [1870 plan, ICBS 07172, left].

New vestries were added

in 1894-96 [ICBS plan 09835, architect E.M.S. Pilkington], the former vestry becoming a side chapel - this altar [right] is now in the side chapel at St George-in-the-East.

New vestries were added

in 1894-96 [ICBS plan 09835, architect E.M.S. Pilkington], the former vestry becoming a side chapel - this altar [right] is now in the side chapel at St George-in-the-East. NINETEENTH CENTURY MINISTRY

See here

for details of the many curates who served in the parish, and here for statistics from the registers.

As

the district had been carved out of St George-in-the-East, Brasenose

College Oxford acquired the patronage, and they appointed a former

Scholar as Quekett's successor. George Henry McGill

(1854-67)

was from an old Irish family but was born in Manchester, son of a pawnbroker, and attended

Manchester Grammar School. Ordained in 1841, he had served curacies in Stockport, Edale,

Stepney and Hilgay in Norfolk, and been Vicar of Stoke Ferry, Norfolk

(a Lord Chancellor's living), where he rebuilt the church and was an

active member of the Norfolk & Norwich Archaeological Society, with

papers on 'The Easter Sepulchre at Northwold' and 'Oxborough Hall'

appearing in vol 4 of their Transactions (1855).

As

the district had been carved out of St George-in-the-East, Brasenose

College Oxford acquired the patronage, and they appointed a former

Scholar as Quekett's successor. George Henry McGill

(1854-67)

was from an old Irish family but was born in Manchester, son of a pawnbroker, and attended

Manchester Grammar School. Ordained in 1841, he had served curacies in Stockport, Edale,

Stepney and Hilgay in Norfolk, and been Vicar of Stoke Ferry, Norfolk

(a Lord Chancellor's living), where he rebuilt the church and was an

active member of the Norfolk & Norwich Archaeological Society, with

papers on 'The Easter Sepulchre at Northwold' and 'Oxborough Hall'

appearing in vol 4 of their Transactions (1855).

He came to

the parish in a harsh winter, with fear of bread strikes among

dockers. Two themes preoccupied him: education (as with his predecessor), and poor-law reform. New classrooms

for the railway arch schools were built, and Sunday services were held here (in his 1861 census

he states that the day schools accommodated 350 boys, 200 girls and 400

infants, and the chapel held 200; there were 200 boys and 275 girls in

the Sunday School). In 1855 the Middlesex Society

Charity School in Cannon Street Road was still short of subscribers and

qualifying children, so was refounded as a National (church) School for

children in the Christ Church district by a scheme of 1862, the

minister chairing the Committee of Management. New buildings were

opened by the Bishop of London. This meant that 1,700 children were

being educated in schools currently or formerly connected to Christ

Church. For

much of his time here he was also Chaplain to St George-in-the-East

workhouse (a post that was later held independently) - see here for more about his campaigning for new attitudes to workhouses and their financing.

He was also Honorary Chaplain to the 10th (Tower Hamlets) Volunteer Corps of

Engineers which had a base at the schoolrooms: C.H.

Gregory was the Captain Commandant and J.A. Coffrey and W.J.

Fraser the Lieutenants. In 1865 he was appointed to a committee of the

Royal Horticultural Society to promote 'widow-gardening by the working

classes' (see here for more details, and also here for a later parish scheme). He was also a Fellow of Sion College - an office which Rectors of St George-in-the-East (but not its 'daughter churches') have held, and continue to hold, ex officio.

In

1856 he

baptized King

William Pepple of the Niger Delta, who was confirmed

three years later by Bishop Tait (see G.O.M.

Tasie Christian

Missionary Enterprise in the Niger Delta 1864-1918, Brill

1978). At the lunch following the service, Pepple refused wine,

saying Water is

best - which delighted Thomas Richarsdon, the

teetotal Vicar of St Matthew Pell Street, who was also present.

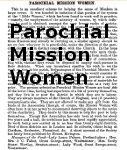

During his time in the parish he had two curates

(with grants of £80 for the senior and £40 for the junior from the

Curates' Aid Society, both of which he made up to £100 from his own

income), a team of district visitors, a Scripture Reader (paid by the

Scripture Readers' Society - was this a national or a diocesan body?),

a nurse for the sick-poor, financed by Mrs Jane Stuart-Wortley

and a 'parochial mission woman' paid by Lady Wood (wife of Sir William

Page Wood, MP for Oxford, briefly Solicitor-General, and then a

vice-chancellor of Oxford University) and the Parochial

Mission Society (see this 1863 report, right, from the [high-church] English Church Union Kalendar). So in comparison with other East End parishes, Christ Church was

well-staffed, but funding for church and schools was always precarious,

and depended on charitable-well wishers (including Miss Chapman)

rather than official sources of income. In his 13 years in the parish

McGill raised £26,000 from private sources; but there was no

fixed endowment, only pew rents of about £250 (falling) and sporadic

collections of about £15 a year.

During his time in the parish he had two curates

(with grants of £80 for the senior and £40 for the junior from the

Curates' Aid Society, both of which he made up to £100 from his own

income), a team of district visitors, a Scripture Reader (paid by the

Scripture Readers' Society - was this a national or a diocesan body?),

a nurse for the sick-poor, financed by Mrs Jane Stuart-Wortley

and a 'parochial mission woman' paid by Lady Wood (wife of Sir William

Page Wood, MP for Oxford, briefly Solicitor-General, and then a

vice-chancellor of Oxford University) and the Parochial

Mission Society (see this 1863 report, right, from the [high-church] English Church Union Kalendar). So in comparison with other East End parishes, Christ Church was

well-staffed, but funding for church and schools was always precarious,

and depended on charitable-well wishers (including Miss Chapman)

rather than official sources of income. In his 13 years in the parish

McGill raised £26,000 from private sources; but there was no

fixed endowment, only pew rents of about £250 (falling) and sporadic

collections of about £15 a year.

In addition to his poor-law activites mentioned above, here

are four documents from his time, showing him to be an astute and well-organised pastor:

| Sundays 11am,

3.30pm and 6.30pm; Wednesdays, Fridays and holy days 11am; Wednesdays

in Lent 7pm; Holy Communion last Sunday of the month and greater

festivals, and quarterly at 6.30pm*; School-Church 11am and 6.30pm; Ragged School Sunday 7pm, Thursday 8pm |

James

Maconechy

(Vicar 1868-71) was the son of James Machonechy MD (1796-1866), member

of the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons in Glasgow, a literary author

and for 23 years editor of the (long-defunct) journal the Glasgow Courier. After Balliol, he served curacies in Sonning (Reading), Kensington and St George

Hanover Square (where William Quekett thought he had been going!) before his appointment here. His first

challenge in the East End was a noisy congregation, with young people courting

invisibly in the high-backed gallery pews, and sidesmen struggling to

keep order. He dealt with this - but at the cost of losing the young

people. He made the customary but controversial 'innovations' of the

time - a choral service with a surpliced choir, the Litany as

a separate service and the new-fangled Harvest Festival (which became

very popular). He also abolished some pew rents in

favour of a

weekly offertory; this was less successful, as it was about this time

that the better-off began to move

away

from the area. In his time the chancel was created,

as

explained

above. He complained when he came that the most prominent object

in the church was the pulpit, secondly the reading desk and thirdly

the clerk's desk.

James

Maconechy

(Vicar 1868-71) was the son of James Machonechy MD (1796-1866), member

of the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons in Glasgow, a literary author

and for 23 years editor of the (long-defunct) journal the Glasgow Courier. After Balliol, he served curacies in Sonning (Reading), Kensington and St George

Hanover Square (where William Quekett thought he had been going!) before his appointment here. His first

challenge in the East End was a noisy congregation, with young people courting

invisibly in the high-backed gallery pews, and sidesmen struggling to

keep order. He dealt with this - but at the cost of losing the young

people. He made the customary but controversial 'innovations' of the

time - a choral service with a surpliced choir, the Litany as

a separate service and the new-fangled Harvest Festival (which became

very popular). He also abolished some pew rents in

favour of a

weekly offertory; this was less successful, as it was about this time

that the better-off began to move

away

from the area. In his time the chancel was created,

as

explained

above. He complained when he came that the most prominent object

in the church was the pulpit, secondly the reading desk and thirdly

the clerk's desk.

The

church responded to the shipbuilders' strike, when many skilled men had

moved elsewhere, leaving unskilled labourers in their wake, by laying

on twice-weekly sewing classes for the wives, with 200-300 attending at

church and the Middlesex Schools and receiving 6d. an hour for their

needlework, funds provided by the Mission and Relief Society. Meetings

ended with a short service and address. Halfpenny dinners were also

provided by the Destitute Children's Dinner Society. Help with

'migration' - to the north of England as well as Canada - was given:

see here and here for others who saw this as a 'solution'. He

succeeded McGill as Honorary Chaplain to the local Engineers, and

played a leading part in a London-wide mission in 1869, issuing an address to the parish: My

dear friends in Jesus Christ, is has pleased God to put into the hearts

of some of His servants to make at this time a great and united effort

for the conversion of sinners and the revival of true religion. For

twelve days we shall entreat God to turn men's hearts from sin to

Himself, and we shall also endeavour, by preaching and exhortations in

church, in schoolrooms, and in private rooms, to bring home the great

truths of the gospel ... (Compare the aversion of Harry Jones, Rector at St George's a few years later, to organised missions).

The

church responded to the shipbuilders' strike, when many skilled men had

moved elsewhere, leaving unskilled labourers in their wake, by laying

on twice-weekly sewing classes for the wives, with 200-300 attending at

church and the Middlesex Schools and receiving 6d. an hour for their

needlework, funds provided by the Mission and Relief Society. Meetings

ended with a short service and address. Halfpenny dinners were also

provided by the Destitute Children's Dinner Society. Help with

'migration' - to the north of England as well as Canada - was given:

see here and here for others who saw this as a 'solution'. He

succeeded McGill as Honorary Chaplain to the local Engineers, and

played a leading part in a London-wide mission in 1869, issuing an address to the parish: My

dear friends in Jesus Christ, is has pleased God to put into the hearts

of some of His servants to make at this time a great and united effort

for the conversion of sinners and the revival of true religion. For

twelve days we shall entreat God to turn men's hearts from sin to

Himself, and we shall also endeavour, by preaching and exhortations in

church, in schoolrooms, and in private rooms, to bring home the great

truths of the gospel ... (Compare the aversion of Harry Jones, Rector at St George's a few years later, to organised missions).

In his time

several initiatives were pioneered at Christ Church. A total

of 26 mission

rooms were hired around the parish, with house-to-house visitors

inviting people who would never come to church to attend evening

'cottage' services,

led by a large clergy and lay team. The first of these was at the Ragged School

at the southern end of

Devonshire [later

Winterton] Street, the worst and most populous street of the parish,

where Maconechy's predecessor had begun to hold services, led by a home missionary (see the comments in his 1861 census). The 1868 map - right - shows the location of 'Christ Church Ragged School' and 'Smith's Place Ragged School' [see below]; the blue line is the underground railway. (See here for the website of a Jewish family who moved into Winterton Street in 1901.).

There were schoolroom services at the railway arches school, teas for the 'unchurched'

(popular, but too costly to repeat) and open-air services of hymns and

preaching, especially in Holy Week. Here is an account from the high-church Church Herald of 27 April 1870:

| Christ Church, St. George's-in-the-East.

– Great praise is due to the Rev. J. Maconechy, Vicar of

Christ Church, St. George's-in-the-East, for the efforts he has made

daring his Incumbency to bring his congregation, and the poor of his

parish who never enter a Church, to value Church privileges. Throughout

Lent Mr. Maconechy had daily Morning and Evening Prayer at 8 a.m. and 6

p.m.; hymns, Litany and short Sermons on Wednesday and Friday evenings

at 8; and Celebration every Sunday at 9 a.m. The hours chosen for

Matins and Evensong we think were rather unfortunate, but especially

Evensong at 6, an hour when very few East-end people could attend,

consequently the attendance was small; but the fact that the Offices

were recited by the Clergy, even if no parishioners attended, was a

great point gained. The congregations at the Litany Services on

Wednesdays and Fridays were very encouraging. From the Pall Mall Gazette we learn how Good Friday was observed by Mr. Maconechy:– While the ordinary congregation were attending Morning Service in Church, the Vicar the Rev. J. Maconechy, and the Rev. J.F.N. Eyre, senior Curate, conducted a series of seven Services in various streets of the parish. Accompanied by the choir boys and several lay helpers, they started from a small Mission room in Devonshire-street, one of the worst streets in the metropolis. The Clergy wore their cassocks and black gowns, and were preceded by the choir, singing the hymn, 'Come, Holy Ghost, Creator, Come!' They took up their position at the foot of the street, where, after prayer, the first short Sermon, or address, was given. It was thought desirable, it is stated, not to take the 'Stations of the Cross', but to confine the addresses to the facts connected with the Crucifixion recorded in the Gospel, and more especially to our Lord's words from the Cross, one of which formed the subject of address in each of the seven streets to which the preachers moved in succession. Mr Maconechy spoke on the first and fourth utterances, 'Father, forgive them', and 'Eli' Eli' lama sabachthani?' Mr. Eyre on the third and seventh, ' Woman, behold thy Son', and 'Father, into Thy hands I commend My spirit'; while the remaining addresses were given by two laymen - Captain Dawson, R.N., and Mr. R. Thomas, of the East London Collegiate School. Each address was preceded by a suitable hymn, and followed by an extempore prayer, offered up by one of the Clergy or by a Scripture-reader or City missionary. In moving from street to street the well known hymn, ' When 1 survey the wondrous Cross', was sung on every occasion, and was heartily joined in by the people, among whom copies of the Christian Knowledge Society's Hymnal were distributed. The other hymns were such well-known ones as 'Rock of Ages', and 'There is a fountain filled with blood'. The last address was delivered opposite the Church, and those present were invited into Church, where the Service was ended with the Litany. It is said that nothing could exceed the quietness and decorum with which the Services were received in the various streets. Everywhere the addresses were listened to with marked attention, not only by the bystanders, but by many at the windows of the houses. Mr Lowder had a Service of a more profound character. |

Evangelical Christendom of 2 May 1870 includes the same account, also approvingly but prefaced with these words which assume, wrongly, that Maconechy was an evangelical:

| OUTDOOR PREACHING ON GOOD FRIDAY On Good Friday last year there was a Ritualistic procession in the East of London with outdoor services. This year simultaneously with similar semi-Romish proceedings, an Evangelical clergyman made an experiment of a somewhat novel character in the district parish of Christ Church, St. George's-in-the-East, in order to bring before the mass of the people the great facts of Good Friday.... |

All of this was moderately

successful, but very hard to sustain. The

Rev H.W. More Molyneux, a Surrey curate, came up for two days each week

to lead this work; the Rev G.P. Ottey also responded to an appeal for

help (see here for details of his brief time as curate, and his cricketing career).

Then, from 1871-93, Maconechy was the Vicar of All Saints,

Norfolk Square in Paddington, a wealthy parish carved out of St James Sussex Gardens, with a Commissioners' church of 1847 by Clutton. Here, according to the high-church weekly Church Herald, he succeeded in thoroughly restoring [i.e. adapting - by creating a quasi-chancel with clergy and choir stalls] his

church ... and of introducing Catholic services. Under the direction of

Mr. Brooks, the architect, the western gallery has been removed, and

the organ moved ... (After

his departure, All Saints burned down in 1894; it was

rebuilt to designs by Ralph Nevill, but closed in 1919, when the parish

was joined to St Michael & All Angels Paddington, and was

subsequently demolished. The later picture [right] ) shows that it remained firmly in the anglo-catholic tradition.) He served on the local

committee of the Charity Organisation Society; according to its Reporter, and in line with its principles, he wrote to The Times

in 1882 suggesting that out-patients at charity hospitals in the

metropolis should pay a nominal shilling, and in-patients half a crown,

which would raise four-fiths of their reported annual deficit of

£75,000. In 1879, according to the National Schoolmaster, he was rebuked for his action in expelling a child from the parish school, according to this letter:

Then, from 1871-93, Maconechy was the Vicar of All Saints,

Norfolk Square in Paddington, a wealthy parish carved out of St James Sussex Gardens, with a Commissioners' church of 1847 by Clutton. Here, according to the high-church weekly Church Herald, he succeeded in thoroughly restoring [i.e. adapting - by creating a quasi-chancel with clergy and choir stalls] his

church ... and of introducing Catholic services. Under the direction of

Mr. Brooks, the architect, the western gallery has been removed, and

the organ moved ... (After

his departure, All Saints burned down in 1894; it was

rebuilt to designs by Ralph Nevill, but closed in 1919, when the parish

was joined to St Michael & All Angels Paddington, and was

subsequently demolished. The later picture [right] ) shows that it remained firmly in the anglo-catholic tradition.) He served on the local

committee of the Charity Organisation Society; according to its Reporter, and in line with its principles, he wrote to The Times

in 1882 suggesting that out-patients at charity hospitals in the

metropolis should pay a nominal shilling, and in-patients half a crown,

which would raise four-fiths of their reported annual deficit of

£75,000. In 1879, according to the National Schoolmaster, he was rebuked for his action in expelling a child from the parish school, according to this letter:

| Sir,-

On the 7th August last your board brought under their lordships' notice

the case of a child named Alice Willsher, who had been dismissed from

the All Saints' School, Paddington, for having absented herself from

the school of the day of inspection. My lords have been in

communication with the Rev. J. Maconechy, the correspondent for the

school, from whose letters it appears that the child had been expressly

warned by the pupil-teacher, and had been present when the mistress had

more than once given public notice that the inspection was about to

take place on the day in question, and that all the children must

attend. The managers considered that if the father was not aware that

he was keeping his child away from the inspection it could have only

been from her purposely omitting to tell him, and that, therefore, her

absence was wilful and deliberate, and an act of disobedience. It was,

moreover, a distinct breach of the law, as the bye-laws specially

required the attendance of all the children on that day. Under

these circumstances, my lords informed Mr. Maconechy that they looked

upon expulsion as an extreme measure, that they were unwilling to

sanction, even in the case of so serious an offence as wilful absence

from the inspection ... |

His first wife wife Laura Sophia, a General's

daughter, died in 1872, and two years later he married Henrietta Clara Marion Baillie, great-niece of the Scottish writer Joanna Baillie; they had a daughter, but Henrietta died in 1878.

On

his departure, having provided cover for a while at Christ Church

Cheltenham (a town which is something of an evangelical stronghold),

from 1893-96 he was Rector of Wiggonholt with Greatham in Sussex. He

was received into the Roman Catholic Church in 1901, in Cheltenham. In

a footnote to an article in The Record entitled 'Perverts [sic!] to Rome: Who and Whence?' - arguing that not all converts were Anglo-Catholics - A.R. Buckland says The

case of the Rev. James Maconechy, a recent pervert, has been made much

of. It is understood that Mr. Maconechy, who was ordained in 1858, was

for many years a Moderate Churchman; but, as he has held no cure since

1896, the general public have no means of knowing through what process

of development he has passed in recent years.

William

Pimblett Insley

(Vicar 1871-80) was born in Warrington; he also came here, after Wadham

College Oxford (a 4th class degree), and curacies in Yorkshire (Kirk

Ella and Flixborough), via the West

End (Christ Church Chelsea). As he arrived, the parish boundaries were

adjusted slightly. He continued work on the church, re-pewing it,

adding a new pulpit and restoring the organ. He started a temperance

society, a cricket club and a drum and fife band. A room in Buross

Street was hired, next to a pub; here Miss Rose began a night school

for girls in 1877 and a women's bible class in 1879.

William

Pimblett Insley

(Vicar 1871-80) was born in Warrington; he also came here, after Wadham

College Oxford (a 4th class degree), and curacies in Yorkshire (Kirk

Ella and Flixborough), via the West

End (Christ Church Chelsea). As he arrived, the parish boundaries were

adjusted slightly. He continued work on the church, re-pewing it,

adding a new pulpit and restoring the organ. He started a temperance

society, a cricket club and a drum and fife band. A room in Buross

Street was hired, next to a pub; here Miss Rose began a night school

for girls in 1877 and a women's bible class in 1879.

In 1871 he wrote to the National Schoolmaster

| A

short time since I advertised in your columns for a non-resident

governess to instruct my two little girls on five half-days a week, and

requested applicants to state the salary required. Fearing lest I might

fail in my object, I had the advertisement inserted in two successive

issues of your paper. But I had grievously miscalculated the

circulation of the Standard, and the number of its readers. Within two

or three hours after the first appearance of my advertisement I

received my first reply; and for two days the stream continued to flow

without intermission. On every round the postman called at my house

with handfuls of letters, which he dealt out like packs of cards; while

a dozen or so of the more determined applicants, probably rendered more

alive to the exigencies of place-hunting by previous ill-success,

called upon me, either personally, or in the person of an interested

friend. I received answers from the daughters of clergymen and

solicitors; answers in French and English: answers answers on paper

pink, white, green, and black edged; answers from ladies in the north,

south, east, and west of London; some of them prepared to come over

daily from Putney and Hammersmith, a distance of certainly not less

than seven miles from my house; answers offering to undertake the

duties for any sum from £10 per annum to £50, though the majority

seemed to think £20 or £25 an adequate return for their labours. I felt

pained, indeed, to cause disappointment to so many, and should have

been glad if I could have offered a post to each of them; but I

wanted one governess — not a hundred — so the thing was obviously

impossible. At first I attempted to acknowledge each reply in writing,

but when the second and third batches of letters came I gave it up;

and, ultimately, not wishing to show a want of courtesy to those who

had been so kind as to write to me, I had a short circular printed and

sent to each one in a stamped wrapper. As they are all readers of your

paper, I trust this letter will meet their eye, and that when they see

it they will pardon the tardy and, apparently, curt answer they

received. |

As explained here, in

1877 the Middlesex Schools were taken over by Raine's Foundation

(as a result of the 1870

Education Act). This meant that Christ

Church lost much of its educational clout, and the attendance of

scholars at church in their charity uniforms; but Mr Insley ensured

that the scheme provided £600 towards the building

of a hall

next to the church in the vicarage gardens, known as Dean [now

Deancross] Street Mission Room - right. It

was opened by

Bishop

Walsham How, Bishop of Bedford (the first 'bishop for East London') in

1881. The Sunday School of 500

scholars transferred from the railway arches, as did some of the Buross

Street work; a senior boys club was started.

| The 'Churches' section of Charles Dickens Jr's Dictionary of London (1879) lists the Sunday services as 11am Matins, Litany & Ante-Communion, 6.30pm Evensong (with Holy Communion on the 2nd Sunday at 8pm), with Matins on Wednesdays and Fridays at 11am. 'Anglican music' was used, and the hymnbook was Ancient & Modern. |

Alfred

Leedes Hunt

(Vicar 1880-83), born in Ipwich, was a former scholar of St John's

College Cambridge,

and had worked in Islington and Spitalfields. He married around the

time he came to Christ Church, and had three children. He arranged for

the church to

take over the small school at the southern end of Devonshire Street run by the Ragged

School

Union (now the Shaftesbury

Society),

where the parish had held Sunday evening services for some years. This

was supported by a fund created by Charles and Maria Sterry (parents of

the

next Vicar's wife - he was chief clerk at the Mint). The

need for such schools had declined with the coming of public funding

for education under the 1870 Act. The school was closed, and the fund

supported work at a mission room in Smith's Place [later renamed Agra

Place - pictured]

which Harry Jones at St George's had started. Buross Street activities

also moved here, as that room was required by the landlord. Another

mission centre was set up in an old cottage in Joseph Street (off Cannon Street Road). The East

London Church Fund made a grant of £150 for a curate, and a

few

years later a further £50 (matched by the Duke of

Westminster)

for a second one. (See 1868 map referred to above for the location of these sites.)

Alfred

Leedes Hunt

(Vicar 1880-83), born in Ipwich, was a former scholar of St John's

College Cambridge,

and had worked in Islington and Spitalfields. He married around the

time he came to Christ Church, and had three children. He arranged for

the church to

take over the small school at the southern end of Devonshire Street run by the Ragged

School

Union (now the Shaftesbury

Society),

where the parish had held Sunday evening services for some years. This

was supported by a fund created by Charles and Maria Sterry (parents of

the

next Vicar's wife - he was chief clerk at the Mint). The

need for such schools had declined with the coming of public funding

for education under the 1870 Act. The school was closed, and the fund

supported work at a mission room in Smith's Place [later renamed Agra

Place - pictured]

which Harry Jones at St George's had started. Buross Street activities

also moved here, as that room was required by the landlord. Another

mission centre was set up in an old cottage in Joseph Street (off Cannon Street Road). The East

London Church Fund made a grant of £150 for a curate, and a

few

years later a further £50 (matched by the Duke of

Westminster)

for a second one. (See 1868 map referred to above for the location of these sites.)

Mr Hunt was also a committee member of

the Charity Organisation Society, and a local Board Schools manager. His handwriting (in the registers) was neat but tiny! He had

another

attempt at abolishing pew rents, keeping collections on the first

Sunday for himself in

lieu! But he became seriously ill and was

told to leave London. For four years he was Rector of New Maldon, and then from 1897 of East Mersea, where he

succeeded Sabine

Baring Gould (who while there had used the local

landscape in Mehalah:

A Story of the Salt Marshes).

It was said that the 'islanders' preferred Hunt to Gould because he was

more

low

church and accessible. Here he wrote a commentary Ruth the Moabitess (1901) for Sunday School teachers, and was

a diocesan inspector of schools. Reflecting the church's renewed

enphasis on confirmation, he produced various manuals over the years: What mean ye by this service? - a question to those who are coming forward to confirmation (1885); Helps and Hindrances: words of counsel and encouragement to those newly confirmed (1885); The King's Table of Blessing: Thoughs for Communicants (1895); and Unto life's end; or, before and after confirmation (1909). From

1903-19 he was Rector of Great Snoring in Norfolk, and Rural Dean of

Walsingham for his last six years there. His final incumbency was of

Moreton in Essex, from where he retired to Cambridge in 1923, having

permission to officiate in Chelmsford and Ely dioceses; in retirement

he published Evangelical By-paths: Studies in the religious and social aspects of the evangelical revival of the 19th century, and David Simpson and the Evangelical Revival (both 1927). He died in 1936, aged 83.

Willie

Parkinson Jay

(Vicar 1883-89) after St Catherine's College Cambridge, he had served his title at St George's, running

the work at Smith's Place, and came after a second curacy in Hackney. He

too was an advocate

of the methods of the Charity Organisation Society,

administering help 'in strict combination' with the organisation and

serving on its local committee. He was also a member of the London School Board from 1885 until he left the parish. His flamboyant brother Arthur Osborne

Montgomery Jay was Vicar of Holy

Trinity, Shoreditch from 1886, serving the slums of the notorious Old

Nichol and creating a boxing club in the church

basement; see here for an account (with corrections) of his ministry there.

Mr

Jay and his wife offered a less controversial, but equally innovative,

style of ministry at

Christ Church. As well as supervising the provision of halfpenny

dinners (41,000 pints of soup one winter) and running the Mothers'

Meeting (which had run for more than 20 years - there were 100 members in 1861), Mrs Jay is credited with

creating the first ever Fathers' Meeting. Bishop Walsham How was

an

honorary member, and after a visit in February 1888 a member sent him a

pair of red leather slippers with this letter:

Willie

Parkinson Jay

(Vicar 1883-89) after St Catherine's College Cambridge, he had served his title at St George's, running

the work at Smith's Place, and came after a second curacy in Hackney. He

too was an advocate

of the methods of the Charity Organisation Society,

administering help 'in strict combination' with the organisation and

serving on its local committee. He was also a member of the London School Board from 1885 until he left the parish. His flamboyant brother Arthur Osborne

Montgomery Jay was Vicar of Holy

Trinity, Shoreditch from 1886, serving the slums of the notorious Old

Nichol and creating a boxing club in the church

basement; see here for an account (with corrections) of his ministry there.

Mr

Jay and his wife offered a less controversial, but equally innovative,

style of ministry at

Christ Church. As well as supervising the provision of halfpenny

dinners (41,000 pints of soup one winter) and running the Mothers'

Meeting (which had run for more than 20 years - there were 100 members in 1861), Mrs Jay is credited with

creating the first ever Fathers' Meeting. Bishop Walsham How was

an

honorary member, and after a visit in February 1888 a member sent him a

pair of red leather slippers with this letter:

| Dear

fellow Farther, We are members of one farthers meeting held at Christ Church, Watney Street, and we long to see you with us again. I do not forget your address when you last came. We were all very much disopointed on Boxing Night. We did expect you, do come as soon as you can. Will you axcept of this little present from me as a fellow farther, belonging to the sam meeting as yourself, and I am glad to be able to say belonging to the sam Saviour and looking forward to the sam rest at last. Yours truly, J.G. |

Mrs Jay's grand-daughter (whose help and

encouragement we gratefully acknowledge) has a

blanket chest presented

to Mrs Jay by the

members of the Christ Church Dorcas Society July 1889 - still used for its

original purpose [pictured right].

Mrs Jay's grand-daughter (whose help and

encouragement we gratefully acknowledge) has a

blanket chest presented

to Mrs Jay by the

members of the Christ Church Dorcas Society July 1889 - still used for its

original purpose [pictured right].

The Bishop of Bedford was also present in 1886 for a royal visit to an exhibition mounted by Christ Church Working Lads' Club. That year, a thousand musicians, mostly in uniform, marched to the church for

the annual demonstration of the bands of East London, where after a

short service the Bishop of London addressed them (Frank Leslie's

Sunday Magazine 1886 p31).

It

was in 1888 that the decorative scheme of the church was completed,

'cheaply [£1400] and in good taste' said Dimsdale [below] whose

book describes everything in great detail. He also completed the task

of abolishing pew rents, making all seats 'free and unappropriated' -

despite the fact that the living was still poorly endowed.

In

1882 he married

Mary Catherine Watson, daughter of Thomas Watson JP, Fellow of the

Royal Astronomical Society and president of the Cape Town Chamber of

Commerce - and a campaigner for a telegraphic landline to Europe.

[Other

sources wrongly describe him as 'Sir Thomas' and 'the premier'; she was

also said to be a great-grand-daughter of Lord Saltoun on her mother's

side.]

Returning from South Africa, in

his short time at Christ Church he set in motion the building of Planet

Street Institute [right],

using most of the £3220 paid in

the form

of stocks by the London and Blackwall Railway for the arches site - the

rest was held as a maintenance fund (and still features in our parish

accounts). Planet Street,

Returning from South Africa, in

his short time at Christ Church he set in motion the building of Planet

Street Institute [right],

using most of the £3220 paid in

the form

of stocks by the London and Blackwall Railway for the arches site - the

rest was held as a maintenance fund (and still features in our parish

accounts). Planet Street,  known from 1865-91 as Star Street, was possibly

the grimmest in the area, and was described in detail by John

Hollingshead in Ragged London

(1861): its road is black and muddy, half filled with pools of inky water; he describes a room inhabited by a chimney sweep with two women, and infant and two children playing on the black floor ... eating what is literally bread and soot. Two

other rooms had nine dwellers, and two more eleven each. The average

rent of the 63 two-up, two-down houses in the street was 1s. 9d. and they

housed 252 families; the average room size was 9' 5" square, the height

8' 5". In Hare's time the adjoining Star Place (six houses) acquired

notoriety for Jack the Ripper connections: it's possible that Elizabeth Stride (who lived in Devonshire Street, the next one along) and Martha Tabram drank at The Star,

2 Morris [previously 22 Duke] Street, on the corner of Star Place. The

pub continued at least until the 1930s, allegedly as a haunt of

transvestites, gangsters and gamblers [right around

1971]. Peter

Kurton writes that a number of Lithuanians, including his own

ancestors,

settled in and around this street from the 1890s, and ran 'cottage

industries' from their homes. He feels that they may have been lumped

together as 'Russians' (since Lithuania was under Russian control),

though in fact they were Catholics with a distinct

identity, and had their own place of worship - originally in Cable Street, and then (and still today) in Bethnal Green. Our thanks to Peter for this and other information about his family.

known from 1865-91 as Star Street, was possibly

the grimmest in the area, and was described in detail by John

Hollingshead in Ragged London

(1861): its road is black and muddy, half filled with pools of inky water; he describes a room inhabited by a chimney sweep with two women, and infant and two children playing on the black floor ... eating what is literally bread and soot. Two

other rooms had nine dwellers, and two more eleven each. The average

rent of the 63 two-up, two-down houses in the street was 1s. 9d. and they

housed 252 families; the average room size was 9' 5" square, the height

8' 5". In Hare's time the adjoining Star Place (six houses) acquired

notoriety for Jack the Ripper connections: it's possible that Elizabeth Stride (who lived in Devonshire Street, the next one along) and Martha Tabram drank at The Star,

2 Morris [previously 22 Duke] Street, on the corner of Star Place. The

pub continued at least until the 1930s, allegedly as a haunt of

transvestites, gangsters and gamblers [right around

1971]. Peter

Kurton writes that a number of Lithuanians, including his own

ancestors,

settled in and around this street from the 1890s, and ran 'cottage

industries' from their homes. He feels that they may have been lumped

together as 'Russians' (since Lithuania was under Russian control),

though in fact they were Catholics with a distinct

identity, and had their own place of worship - originally in Cable Street, and then (and still today) in Bethnal Green. Our thanks to Peter for this and other information about his family.

His wife Mary died in 1897 (in Bournemouth), and in 1901 he left rather suddenly (press reports spoke of a mysterious disappearance from the East End) to visit the USA, where he became incumbent of St Paul Albany, and the following year Rector of St George Toronto. Four years later he was Rector of All Saints Milford, in Connecticut, and in 1907 became Dean of Grace Cathedral in Davenport, Iowa, which soon after joined with Trinity church (built 1873) as Trinity Cathedral - he was, apparently, acceptable to both congregations. In 1910 he re-married:

| This morning (28 June) at 11 o'clock took place the marriage of Very Rev.

Marmaduke Hare, dean of Trinity cathedral, Davenport, and Miss Anna

Lyster, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Armstrong B. Lyster of Lyster island,

near Breedsville, Mich., the ceremony taking place at St. Peters

Episcopal church, Chicago. The Very Rev. T. N. Morrison, bishop of Iowa

and head of the church with which Dean Hare is connected, officiated.

The bridal couple was unattended and the ceremony was witnessed by a

small company of relatives and near friends, the decorations and

appointments being simple. Following the ceremony Dean Hare and his

bride left for an extended wedding trip to the Pacifio coast. On their

return they will reside at the New Kimball till fall when they will go

to housekeeping in the Kiser house on Perry street. The bride is of an old English family, her grandfather having been governor of Nova Scotia, coming there from England, and she is a woman of culture and education. Mrs. William Kiser, of Salt Lake City, is a cousin and it was while visiting at her home that Dean Hare met his bride-elect. Dean Hare has been in this country nine years, coming here from England. In east London he had been associated with the leading dignitaries of his church and was acquanited with men and women in high court circles ... He is a man of broad knowledge, having travelled extensively, being a chaplain in the Congo war, and withall a brilliant man. Mrs Hare will be heartily welcomed to tri-city [Davenport, Rock Island and Moline] society. |

In that same year, Billboard

announced that comedian William Collier had arranged by telephone to

marry the leading lady from his company Pauline Marr at the cathedral,

but when they arrived and the Dean discovered he was divorced he

was advised to take his affianced to the pastor of a church of

different denomination, as marriage under such circumstances was

contrary to the laws of the Episcopal faith. However, the report continued, Dean

Hare is an admirer of Mr. Collier as an actor, as was evidenced by his

attendance at his performance at the Grand Opera House. (Compare this account of the marriage of a divorcee in 1903 by R.H. Hadden, former curate of St George-in-the-East.)

In that same year, Billboard

announced that comedian William Collier had arranged by telephone to

marry the leading lady from his company Pauline Marr at the cathedral,

but when they arrived and the Dean discovered he was divorced he

was advised to take his affianced to the pastor of a church of

different denomination, as marriage under such circumstances was

contrary to the laws of the Episcopal faith. However, the report continued, Dean

Hare is an admirer of Mr. Collier as an actor, as was evidenced by his

attendance at his performance at the Grand Opera House. (Compare this account of the marriage of a divorcee in 1903 by R.H. Hadden, former curate of St George-in-the-East.)

Henry

Cockfield Dimsdale

(1892-1909) was born in Palace Green Gardens, Kensington in 1856 and was a pupil at

Eton, leaving after four happy years because of serious illness.

After Trinity College Cambridge and a spell of foreign travel, he spent

a year at Leeds

Clergy School but left, to study law for a time. As a layman, he became

one of a

famous pioneering trio of Etonians at the college's temporary iron mission church in Hackney Wick, where Bodley's great church St Mary of Eton now stands. (The other two, both ordained, were Willy Carter [right], who began the mission and later became Bishop of Zululand, then of Pretoria, then Archbishop of Capetown; and Algy Lawley (also ex-Leeds Clergy School), who later served in various East and West End parishes, and became the 5th Baron Wenlock.) After

ordination and a further period of rest Dimsdale was appointed to Christ

Church.

Henry

Cockfield Dimsdale

(1892-1909) was born in Palace Green Gardens, Kensington in 1856 and was a pupil at

Eton, leaving after four happy years because of serious illness.

After Trinity College Cambridge and a spell of foreign travel, he spent

a year at Leeds

Clergy School but left, to study law for a time. As a layman, he became

one of a

famous pioneering trio of Etonians at the college's temporary iron mission church in Hackney Wick, where Bodley's great church St Mary of Eton now stands. (The other two, both ordained, were Willy Carter [right], who began the mission and later became Bishop of Zululand, then of Pretoria, then Archbishop of Capetown; and Algy Lawley (also ex-Leeds Clergy School), who later served in various East and West End parishes, and became the 5th Baron Wenlock.) After

ordination and a further period of rest Dimsdale was appointed to Christ

Church.

When Planet Street Institute opened in 1892, Smith's

Place was closed and the Sterry Fund transferred. Most parish

activities moved here, and new ones

were started, including a Saturday School initiated by Miss Helen

Cunliffe (who was previously linked with the Sisters of the Church,

founded at

Kilburn in 1870, and now based at Ham Common; in 1895 she became

headmistress of Holy Cross School, Bournemouth so had presumably become

a Roman Catholic). This attracted about 200

children, pictured here in 1900, with a mixture of activities, play in

the vicarage

gardens, and an annual examination.

When Planet Street Institute opened in 1892, Smith's

Place was closed and the Sterry Fund transferred. Most parish

activities moved here, and new ones

were started, including a Saturday School initiated by Miss Helen

Cunliffe (who was previously linked with the Sisters of the Church,

founded at

Kilburn in 1870, and now based at Ham Common; in 1895 she became

headmistress of Holy Cross School, Bournemouth so had presumably become

a Roman Catholic). This attracted about 200

children, pictured here in 1900, with a mixture of activities, play in

the vicarage

gardens, and an annual examination.

The 1886

Census

of London church attendance, conducted on 24 October, had recorded

large congregations - 234 in the morning, and 254 in the evening. A

decade later, now with three curates (one of them, A.M. Cazalet,

secretary of the East

London Mission to the Jews), and a lay team of

locals and volunteers from further afield, plus two Clewer sisters, an

astonishingly busy weekly

programme was run - displayed, with a picture of the clergy team, here -

including twelve bible classes for

various groups which fed into the two main ones run by the vicar and

senior curate. The club for 'rougher girls' continued, as did one

long-standing 'cottage' meeting.

There was a communicants guild with four wards (St Alban, St Anne, St

George and the St Mary the Blessed Virgin); various men's activities,

including a Chapter of the Brotherhood of St Andrew, replaced the

Fathers' Meeting. 'Mr Elliott's Club' (the junior curate) met every

night of the week except Sundays; he clearly won the confidence of

those who, as Dimsdale put it, were verging on

criminality...possibly

the world would call them hooligans. And the number of

daily services

increased, with a daily eucharist. New vestries were built, and the

old one became a side chapel.

The 1886

Census

of London church attendance, conducted on 24 October, had recorded

large congregations - 234 in the morning, and 254 in the evening. A

decade later, now with three curates (one of them, A.M. Cazalet,

secretary of the East

London Mission to the Jews), and a lay team of

locals and volunteers from further afield, plus two Clewer sisters, an

astonishingly busy weekly

programme was run - displayed, with a picture of the clergy team, here -

including twelve bible classes for

various groups which fed into the two main ones run by the vicar and

senior curate. The club for 'rougher girls' continued, as did one

long-standing 'cottage' meeting.

There was a communicants guild with four wards (St Alban, St Anne, St

George and the St Mary the Blessed Virgin); various men's activities,

including a Chapter of the Brotherhood of St Andrew, replaced the

Fathers' Meeting. 'Mr Elliott's Club' (the junior curate) met every

night of the week except Sundays; he clearly won the confidence of

those who, as Dimsdale put it, were verging on

criminality...possibly

the world would call them hooligans. And the number of

daily services

increased, with a daily eucharist. New vestries were built, and the

old one became a side chapel.

For the third time patronage was transferred, this time to the Dean and and Canons of Canterbury (together with two other East End parishes), and the endowment increased by £300 through the voidance of All Hallows, Lombard Street to produce a stipend of £468, ending its claim of being the poorest parish in East London.

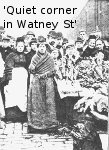

Watney Street remained a 'colourful' thoroughfare.

In Round London:

Down East and Up West Montagu Williams QC commented, in 1894,

| While acting as one of the magistrates of the Worship Street district it was a part of my duty to sit on certain days at the Thames Police Court. I found that the most convenient way to reach it from the West End was to go by the underground railway from Baker Street to Shadwell and proceed thence on foot. The distance from the railway station to the Court is an inconsiderable one but the best route is through Watney Street, which is the most disgraceful thoroughfare I was ever doomed to traverse. On either side of the way are poor, squalid shops. Throughout the day the road and the pavement are crowded with barrows laden with fish, vegetables, and other articles of food, cheap second-hand furniture, old iron, rabbit skins, and many articles besides. So great is the throng of dirty and ragged human beings that it is very difficult to make one’s way through the street. There is a good deal of unceremonious shoving in the crowd, but to remonstrate thereat would be to run a very good chance of being sent rolling in the gutter. A few policemen pick their way through the street, but I think they would be slow to incur the displeasure of such an evil-looking crowd. The stench in Watney Street is sickening. It arises for the most part from the greasy mash formed underfoot by the miscellaneous refuse from the barrows. Needless to say, this pandemonium contains a number of thriving public-houses. The women who infest the place are of a lower order than those to be met with in the Ratcliff Highway of to-day. When you gaze on their brutal and vicious faces, soddened with drink, you have a difficulty in believing that such beings are fellow human creatures. |

There

is an 1897 interview with

Dimsdale in the Booth

archive. In

that year, when his mother Catharine died, he and his sister gave

a set of gilt communion vessels (patens, cruets and chalice)

which we still use in festal seasons at St George-in-the-East.

In 1901 he wrote Sixty

Years'

History of an East End Parish, Christ Church, St.

George's-in-the-East (Henry

Bailey 1901), from which

much of the detailed information above is taken. The British

Archaeological Association patronisingly and stupidly hailed this book as a fine

example of what can be achieved even with a most unpromising subject, because modern

and poor. See here

for a brief account of a service at Christ Church attended by a

'reporter' for the Royal Commission on Ecclesiastical Discipline in

1904, and Dimsdale's equally brief response.

He married in 1909, at the age of 52, and had two children. An

intriguing remark

from his latter years was the

white motor

ambulance is almost as much as part of our city life as is the red

motor omnibus. He died in 1918, and was buried at Highgate Cemetery.

THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

See here for details of the curates from this period - including several who 'filled in' for short periods.Arthur

Stevens was

Vicar from 1909-16. Ordained in in 1882 in Durham where he had studied

at the university (as a non-collegiate member - a system instituted in

1871), he worked his way south with four further curacies along the

way, becoming Rector of St Mildred Canterbury

in 1896 (receiving a testimonial from his former parishioners in the

city). After two further incumbencies, in Burgess Hill and Kilburn, he

came to the parish at the age of 60. In retirement he held permission

to officiate in no less than six dioceses at various times, eventually

settling in St Leonards-on-Sea, where he died in old age.

William

Holmes Shuter succeeded

him (1916-28); from county Tyrone (he played rugby football at

Dungannon Royal School), he trained at Trinity College

Dublin, was ordained in

Chester diocese in 1888 and was curate of Tarvin, then of Knutsford,

then of two parishes in Southwark diocese (St Luke Bromley Common and

St Michael Croydon) before coming to the parish, with a net stipend of

£358. (His father James Coote Shuter had died in 1914 at

Barnhill, Stewartstown in country Tyrone, leaving an estate of around

£5,000.) He retired to Herne Hill, living to a good age.

William

Holmes Shuter succeeded

him (1916-28); from county Tyrone (he played rugby football at

Dungannon Royal School), he trained at Trinity College

Dublin, was ordained in

Chester diocese in 1888 and was curate of Tarvin, then of Knutsford,

then of two parishes in Southwark diocese (St Luke Bromley Common and

St Michael Croydon) before coming to the parish, with a net stipend of

£358. (His father James Coote Shuter had died in 1914 at

Barnhill, Stewartstown in country Tyrone, leaving an estate of around

£5,000.) He retired to Herne Hill, living to a good age.

Right is the interior in 1927; see here for

the story of the shops and stalls of Watney Market next door.

In

1929, when the church was in the doldrums and its future uncertain, St

John Beverley Groser was appointed as Vicar, on the basis that he could do little harm! In the event, he re-energised the parish, and the

remarkable story of

his ministry, at Christ Church and then at St George-in-the-East, is told here. One of the thurifers in those days was J.C.

(Jimmy) Mooney, now living in Colchester. He has fond memories of Frs

Groser and Boggis, who had the sad task of burying nine family members

killed in Blakesley Street during the Blitz (several other relatives

died in the Far East). For details of Fr Groser's curates, see here. (Blakesley Street was originally Upper and Lower John Street; right are 34-58, and 21-23 on the corner of Deancross Street, in 1958.)

In

1929, when the church was in the doldrums and its future uncertain, St

John Beverley Groser was appointed as Vicar, on the basis that he could do little harm! In the event, he re-energised the parish, and the

remarkable story of

his ministry, at Christ Church and then at St George-in-the-East, is told here. One of the thurifers in those days was J.C.

(Jimmy) Mooney, now living in Colchester. He has fond memories of Frs

Groser and Boggis, who had the sad task of burying nine family members

killed in Blakesley Street during the Blitz (several other relatives

died in the Far East). For details of Fr Groser's curates, see here. (Blakesley Street was originally Upper and Lower John Street; right are 34-58, and 21-23 on the corner of Deancross Street, in 1958.)

Dan Regan, who later was to become Director of Finance, and then Chief Executive, of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, also lived in Blakesley Street - his family were members of St Mary & St Michael's Roman Catholic Church on Commercial Road. In 2011 he wrote

| As

a small boy, I and others used to creep into the church and ring the

bell until we were chased away by Fr Groser's wife. When I was 8, my

family and I were buried in the first raid on London on 7 September