St

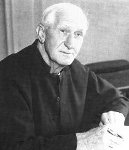

John Beverley Groser (1890-1966)

and Michael Groser (1918-2009)

John

Groser [left - sketch by Ronald Searle] was the most famous – or infamous, depending on your

point

of view! - priest to serve this parish in the 20th century. He was the Vicar of Christ

Church, Watney Street from 1929-48, and when this and other churches

were blitzed, Curate-in-charge of St George-in-the-East and St John

Golding Street from 1941 to 1947. Much has been written about him and

the context in which he worked. This page is indebted to his

biography, edited by Kenneth Brill John

Groser – East London Priest

(Mowbray

1971), to the many writings and web-postings of Ken Leech,

recorder-supreme of all things Christian Socialist (see extracts from his Oxford DNB entry below) and

to

conversations with East Enders who remember 'The Old Man'. There is

also a Groser family website.

John

Groser [left - sketch by Ronald Searle] was the most famous – or infamous, depending on your

point

of view! - priest to serve this parish in the 20th century. He was the Vicar of Christ

Church, Watney Street from 1929-48, and when this and other churches

were blitzed, Curate-in-charge of St George-in-the-East and St John

Golding Street from 1941 to 1947. Much has been written about him and

the context in which he worked. This page is indebted to his

biography, edited by Kenneth Brill John

Groser – East London Priest

(Mowbray

1971), to the many writings and web-postings of Ken Leech,

recorder-supreme of all things Christian Socialist (see extracts from his Oxford DNB entry below) and

to

conversations with East Enders who remember 'The Old Man'. There is

also a Groser family website.He was one of 11 children of Thomas Eaton Groser, an American-born missionary who had worked among North American Indians, and English-born Phoebe Wainwright, who had worked in Labrador. He name reflects the date (the Nativity of St John the Baptist) and place of his birth (Beverley, a remote cattle station in Western Australia where his father was Rector). He retained a deep fondness for Australia, where other family members remained, though from the time he came to England as a teenager did not return until he retired.

He lodged with a rather grand family, and attended Ellesmere School, one of the schools of the anglo-catholic Woodard Foundation, before training with the Community of the Resurrection at Mirfield (in contrast to his two older brothers, who trained at St Augustine's College Canterbury). Study was a struggle because his education in Australia had been rudimentary.

From

1914 he was a curate All Saints Newcastle-upon-Tyne, a tough slum

parish, and the experience radicalised him: he was puzzled when the

bishop complained he had been sent there to save souls, not bodies.

Service as a front line chaplain to the Forces in France continued to

shape his uncompromising views – and turned his hair white.

His

commanding officer put him in charge of a group of demoralised men in

a time of heavy casualties. He was mentioned in dispatches in 1917,

sent home wounded and received the Military Cross in the following

year.

From

1914 he was a curate All Saints Newcastle-upon-Tyne, a tough slum

parish, and the experience radicalised him: he was puzzled when the

bishop complained he had been sent there to save souls, not bodies.

Service as a front line chaplain to the Forces in France continued to

shape his uncompromising views – and turned his hair white.

His

commanding officer put him in charge of a group of demoralised men in

a time of heavy casualties. He was mentioned in dispatches in 1917,

sent home wounded and received the Military Cross in the following

year.

In

1917 he met and married Mary

Agnes Bucknall (1893-1970) [right, 1919] at St Winnow Cornwall, where her father was vicar. It was a

devoted partnership, and she was central to everything that he later

did. They had two sons and two daughters. Her sister Nancy married

Charles (Carl) Threlfall Richards, who had been at Mirfield with

Groser, and was to serve as his curate at St George's for a time.

In

1917 he met and married Mary

Agnes Bucknall (1893-1970) [right, 1919] at St Winnow Cornwall, where her father was vicar. It was a

devoted partnership, and she was central to everything that he later

did. They had two sons and two daughters. Her sister Nancy married

Charles (Carl) Threlfall Richards, who had been at Mirfield with

Groser, and was to serve as his curate at St George's for a time.

It

was hard to place such a man after the war; he did a year as

Messenger for the Church of England Men's Society in Carlisle, Durham

and Newcastle dioceses, but this was no good, because he did not

believe men could be brought back to the church as it had been. So he

went to Cornwall, as curate at St Winnow, to reflect on his future.

Mary's brother Jack had become curate to Conrad Noël, the 'Red Vicar' of Thaxted and introduced him to his Catholic Crusade. John was totally captivated by the ethos of

Thaxted – the Red Flag, the liturgy, the music, which were

all of a

piece – and later did temporary duty there. Of the Crusade's

creed/manifesto he said a bit

unbalanced, but still pretty splendid, don't

you think? (Compare this with the 1947 Socialist Christian Catechism by Frs Gresham Kirby and Jack Boggis.) Conrard Noël: an

Autobiography (Dent 1945, p107f) refers briefly to Groser's

time at Watney Street.

The

Crucifix, the Red Flag, and the Flag of St George

From 1922-28 John Groser and his brother-in-law Jack Bucknall were curates at St Michael Poplar, under Fr C.G. Langdon. The two families lived next door to each other in Teviot Street, where many meetings were held. They rubbed shoulders with the great East End political figures of the day – George Lansbury (Leader of the Opposition), Mary Hughes, Basil Henriques – and were a part of 'Poplarism', a 'can-do' form of direct action in the face of bureaucracy.

John

and Jack held many street corner meetings for the Catholic Crusade [left, 1920s],

always dressed in cassocks and flanked by the three symbols of the

crucifix, the Red Flag, and the flag of St George. (Groser had no time

for the Union Jack: scouts at Christ Church were only

permitted to parade the George, and their neckerchiefs,

significantly, were red.) Whatever the meetings had been called for,

the message was always about the kingdom, or commonwealth, of God. So

get organised, they told the unemployed; claim your God-given dignity

and show the authorities who you really are. He was beaten by police

batons in the General Strike. His licence was removed for a time.

John

and Jack held many street corner meetings for the Catholic Crusade [left, 1920s],

always dressed in cassocks and flanked by the three symbols of the

crucifix, the Red Flag, and the flag of St George. (Groser had no time

for the Union Jack: scouts at Christ Church were only

permitted to parade the George, and their neckerchiefs,

significantly, were red.) Whatever the meetings had been called for,

the message was always about the kingdom, or commonwealth, of God. So

get organised, they told the unemployed; claim your God-given dignity

and show the authorities who you really are. He was beaten by police

batons in the General Strike. His licence was removed for a time.

Other

Thaxted-inspired parts of his message may have been more surprising

to East Enders. Jim Desormeaux, who attended many of these meetings

and became a parishioner at Christ Church (and later at St George-in-the-East), commented The

drabness of the Poplar homes was anathema to Groser. Get colour in

your lives and in your homes, he would urge. Do away with your lace

curtains and aspidistra plants; away with the dark brown and green

paints. Did

local folk share his enthusiasm for country dancing – or

(rather

less Thaxted) sword-dancing – as embodiments of the gospel?

There

was continual conflict with Fr Langdon and his successor Fr Ashcroft,

even though both shared many of Groser's view and ideals, and with

Winnington-Ingram, the Bishop of London, who, it was said, didn't

understand what he was about but recognised him as a gentleman! There

were threats of sacking; in the end, Groser resigned. A year of

unemployment followed – he did not sign on, as he threatened,

but

supported his family by Sunday duties, selling life insurance, and

some craft work.

Christ Church, Watney Street

In

1929 he was appointed to Christ Church, Watney Street. A commission

on its future had sat for six months, and it was felt that he could

do no harm in this hopeless situation. In the event, he transformed

it, and put it on the map. High Mass and Solemn Evensong, both with

incense (previously only occasionally used) were flamboyantly

celebrated with Thaxted-style ceremonial. The church was re-ordered

with a more open sanctuary [right in 1928 and 1932, showing the contrast] and limewashed, with

banners – St

George (the parish church) and the blood-red people's banner 'He has

made of one blood all nations'. He had become a skilled weaver, and

made many of the hangings and vestments himself – we still

wear

his

hand-blocked unbleached holland Lenten chasuble at St George's. Out

went sentimental music, and (with Mary as the organist, and from 1936 a

new and smaller organ

by Cedric Arnold, a Thaxted builder) in came Bach

and Byrd, with hymns that combined radical politics and romantic

pastoral nostalgia, such as Charles Dalmon's text, usually sung to the tune

'We plough the fields, and scatter', which included the verse (full text here in a 'modernised' version by Ken Leech; see here for connections with present-day St Georgestide events):

In

1929 he was appointed to Christ Church, Watney Street. A commission

on its future had sat for six months, and it was felt that he could

do no harm in this hopeless situation. In the event, he transformed

it, and put it on the map. High Mass and Solemn Evensong, both with

incense (previously only occasionally used) were flamboyantly

celebrated with Thaxted-style ceremonial. The church was re-ordered

with a more open sanctuary [right in 1928 and 1932, showing the contrast] and limewashed, with

banners – St

George (the parish church) and the blood-red people's banner 'He has

made of one blood all nations'. He had become a skilled weaver, and

made many of the hangings and vestments himself – we still

wear

his

hand-blocked unbleached holland Lenten chasuble at St George's. Out

went sentimental music, and (with Mary as the organist, and from 1936 a

new and smaller organ

by Cedric Arnold, a Thaxted builder) in came Bach

and Byrd, with hymns that combined radical politics and romantic

pastoral nostalgia, such as Charles Dalmon's text, usually sung to the tune

'We plough the fields, and scatter', which included the verse (full text here in a 'modernised' version by Ken Leech; see here for connections with present-day St Georgestide events):

| God is the only landlord to whom our rents are due; he made the earth for all men and not for just a few. The four parts of creation - earth, water, air and sky - God made and blessed and stationed for ever man's desire. Uplift Saint George's banner, and let the ancient cry 'Saint George for Merrie England' re-echo to the sky. |

The

congregation expanded, though many on the Electoral Roll were

Catholic Crusaders rather than local worshippers. At this time there

was factional division among left-wing groups over Stalinism, and

after long and bitter discussion John and Mary Groser and the group

at Christ Church were driven out of the Crusade in March 1932,

shifting to various other alliances, principally the Socialist

Christian League [right in 1937].

In that year, Christ Church held a conference on

poverty in the East End and the administration of the Poor Law; Groser

wrote and spoke a good deal on unemployment. He opposed means testing

and the use of police powers over 'loitering with intent' against the

unemployed, and was a member of the LCC committee on poor relief

applications and chair of the local public assistance committee.

The

congregation expanded, though many on the Electoral Roll were

Catholic Crusaders rather than local worshippers. At this time there

was factional division among left-wing groups over Stalinism, and

after long and bitter discussion John and Mary Groser and the group

at Christ Church were driven out of the Crusade in March 1932,

shifting to various other alliances, principally the Socialist

Christian League [right in 1937].

In that year, Christ Church held a conference on

poverty in the East End and the administration of the Poor Law; Groser

wrote and spoke a good deal on unemployment. He opposed means testing

and the use of police powers over 'loitering with intent' against the

unemployed, and was a member of the LCC committee on poor relief

applications and chair of the local public assistance committee.

Jack Boggis, whose vocation had been inspired by Groser at Poplar, came as

curate (1932-36) and produced the radical Christ

Church

Monthly – he

was to succeed

Groser as Rector at St George's. Here

is his

tribute to his great mentor. Controversially, Groser disposed of Planet

Street

Institute to enable facilities at the church hall ('Dean

Street

Parish Room', in the vicarage garden) to be improved. The

ever-open vicarage [left in 1929],

with Mary somehow providing food and welcome for

all comers, was at the heart of parish life.

Jack Boggis, whose vocation had been inspired by Groser at Poplar, came as

curate (1932-36) and produced the radical Christ

Church

Monthly – he

was to succeed

Groser as Rector at St George's. Here

is his

tribute to his great mentor. Controversially, Groser disposed of Planet

Street

Institute to enable facilities at the church hall ('Dean

Street

Parish Room', in the vicarage garden) to be improved. The

ever-open vicarage [left in 1929],

with Mary somehow providing food and welcome for

all comers, was at the heart of parish life.

In

these years he galvanised local opposition to Mosley, addressing both

the community and the police (see Kenneth Leech Struggle in Babylon: racism in

the cities and churches of Britain (Sheldon 1988) p97f). He took part in the Battle of Cable Street in 1936, and had his nose broken by a police baton. He

helped found, and from 1938 was president of,

the Stepney Tenants' Defence League, a broad-based grouping, many of whose activists were

Jewish and/or Communists; it had begun with surgeries in the vicarage. He later reflected, in Politics and Persons how the tenants' movement revitalised people from the defeatism of the depression by showing them a possible way out of at least one of their problems, and was amazed at the

speed with which people came together, organised, and threw up their

own leaders ... In spite of all their sufferings the masses generally

were still far from accepting the Communist philosophy ... but I

sometimes wonder what would have happened if the war had not come when

it did. Things were pretty desperate. It is just possible that the

workers would have turned to open revolutionary activity and looked to

the Communist Party for leadership. Certainly there were a great many

who were thinking that way and looking in that direction for guidance (pp 73-75). See further Sarah Glynn East End Immigrants and the Battle for Housing: a comparative study of political mobilisation in the Jewish and Bengali communities (Journal of Historical Geography 31 pp528-545, 2005).

The Communist activist and MP for Mile End 1945-50 Phil Piratin commented in Our Flag Stays Red (1948):

| Blackmail

has succeeded. The threat of force has triumphed ... That Mr

Chamberlain should talk of 'peace with honour' when he has surrendered

to this blackmail, torn up Article 10 of the League Covenant without

reference to Geneva, and scarificed the Czechoslovaks in order, as he

says, to prevent a world war, is bad enough; but that the Archbishop of

Canterbury should say that this is the answer to our prayers ... is

beyond endurance. quoted in Adrian Hastings A History of English Christianity 1920-1985 (Collins 1986) p349 |

When war came, he displayed characteristically heroic

care

for his people, with little regard for his own welfare and

reputation. In 1940 he broke into an official food store

and

distributed rations to homeless people and organized buses to take

them to places of safety. He wrote scathingly about the arrangements

made for East Enders. He was involved in the creation of a railway arch air-raid shelter in Watney Street. Here

is a newspaper article, 60 years on, about his wartime

activities, by the great Bob Holman.

St George's and after

Fr Groser's

ministry at Christ Church ended abruptly when the church and vicarage

were destroyed by a landmine on 16 April 1941; St George's was

blitzed the following month. The family, together with their

livestock (including chickens, who nibbled the carpets) moved to St

George's Rectory, and for

the next six years he led the ministry of the combined parishes of

Christ Church, St John's and St George's, together with his

brother-in-law Carl Richards (briefly), then Geoffrey Lough, and Denys

Giddey,

as curates, and in due course Ethel Upton

as parish worker. The phone number was

then (and recognisably still is) ROYal 1345 - perhaps a sign that the radical was about to embrace aspects of the establishment.

Fr Groser's

ministry at Christ Church ended abruptly when the church and vicarage

were destroyed by a landmine on 16 April 1941; St George's was

blitzed the following month. The family, together with their

livestock (including chickens, who nibbled the carpets) moved to St

George's Rectory, and for

the next six years he led the ministry of the combined parishes of

Christ Church, St John's and St George's, together with his

brother-in-law Carl Richards (briefly), then Geoffrey Lough, and Denys

Giddey,

as curates, and in due course Ethel Upton

as parish worker. The phone number was

then (and recognisably still is) ROYal 1345 - perhaps a sign that the radical was about to embrace aspects of the establishment.

The

man thought unemployable had become acceptable! He was now much in

demand as a speaker and occasional broadcaster; was Select Preacher

at Cambridge University in 1941; from 1943-45 a member of the

Bishop of Rochester's group which produced the report Towards the

Conversion

of England (commissioned by the Archbishops to identify a mission strategy for the post-war world: it had limited impact);

was associated with

Archbishop William Temple's Religion and Life Movement (an ecumenical

campaign launched in1940 stemming from the 1937 Oxford Conference on

Church, Community and State); became a

member of the Church of England Board for Social Responsibility;

toured theological colleges after the war; and was Rural Dean of

Stepney from 1945-56. Back home, he was instrumental in setting up Stepney Old Peoples' Welfare Association in 1947 [now Tower Hamlets Friends & Neighbours]. There was even talk of 'preferment'.

The

man thought unemployable had become acceptable! He was now much in

demand as a speaker and occasional broadcaster; was Select Preacher

at Cambridge University in 1941; from 1943-45 a member of the

Bishop of Rochester's group which produced the report Towards the

Conversion

of England (commissioned by the Archbishops to identify a mission strategy for the post-war world: it had limited impact);

was associated with

Archbishop William Temple's Religion and Life Movement (an ecumenical

campaign launched in1940 stemming from the 1937 Oxford Conference on

Church, Community and State); became a

member of the Church of England Board for Social Responsibility;

toured theological colleges after the war; and was Rural Dean of

Stepney from 1945-56. Back home, he was instrumental in setting up Stepney Old Peoples' Welfare Association in 1947 [now Tower Hamlets Friends & Neighbours]. There was even talk of 'preferment'.

In

1948, after a sabbatical in Germany, he was

appointed as Master

of the Royal

Foundation of St Katharine,

which was being brought back

to the East End where it properly belonged (founded in 1147, with a

charge to pray daily for the soul of Queen Matilda, it had been

displaced from what became St Katharine's Dock to Regent's Park in

1825 - see here for more detail). While building work was being done, the family lived at 400 Commercial Road,

the parsonage house of the closed church of St John the

Evangelist-in-the-East. He was at St Katharine's for the

last fourteen years of his ministry, supported by a lay community of

which Olive Wagstaff from our congregation was an original member,

before it was replaced by male and female members of religious orders.

There he wrote Politics

& Persons (1949), and

in

1951 helped found, together with the local Franciscans, the Stepney Coloured

People's [sic] Association, of which he became President. Right is

his farewell at the Stepney OAP's Garden Party held at St Katharine's,

where he was presented with a tobacco pouch and electric fire (the Lady

Mayor of Stepney is seated, and Olive Wagstaff and Tom Whiting

are on the right). Left is a 1962 profile, 'Father Figure', from The Guardian - click to read the text.

In

1948, after a sabbatical in Germany, he was

appointed as Master

of the Royal

Foundation of St Katharine,

which was being brought back

to the East End where it properly belonged (founded in 1147, with a

charge to pray daily for the soul of Queen Matilda, it had been

displaced from what became St Katharine's Dock to Regent's Park in

1825 - see here for more detail). While building work was being done, the family lived at 400 Commercial Road,

the parsonage house of the closed church of St John the

Evangelist-in-the-East. He was at St Katharine's for the

last fourteen years of his ministry, supported by a lay community of

which Olive Wagstaff from our congregation was an original member,

before it was replaced by male and female members of religious orders.

There he wrote Politics

& Persons (1949), and

in

1951 helped found, together with the local Franciscans, the Stepney Coloured

People's [sic] Association, of which he became President. Right is

his farewell at the Stepney OAP's Garden Party held at St Katharine's,

where he was presented with a tobacco pouch and electric fire (the Lady

Mayor of Stepney is seated, and Olive Wagstaff and Tom Whiting

are on the right). Left is a 1962 profile, 'Father Figure', from The Guardian - click to read the text.

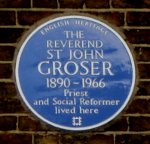

In 1990 a blue plaque was placed at St Katharine's,

describing him as a 'priest and social reformer'. The late Queen

Mother, as patron, was closely associated with the Foundation (local

clergy claim to have sipped her discarded glasses of gin and Dubonnet). The

Queen is the current patron, and visited in 2011 for the 60th

anniversary of the dedication of the chapel - said to have had the

first central altar in this country, over which hung a stark metal

corona (now gone, and various other changes have been made). A display

of photographs, including some characteristic shots of Fr Groser, was

mounted for the occasion. Read his Church Times obituary [right - 25 March 1966], and the letter from his one-time curate Denys Giddey, protesting against his depiction by A. Tindal Hart in Some Clerical Oddities (New Horizon 1980).

In 1990 a blue plaque was placed at St Katharine's,

describing him as a 'priest and social reformer'. The late Queen

Mother, as patron, was closely associated with the Foundation (local

clergy claim to have sipped her discarded glasses of gin and Dubonnet). The

Queen is the current patron, and visited in 2011 for the 60th

anniversary of the dedication of the chapel - said to have had the

first central altar in this country, over which hung a stark metal

corona (now gone, and various other changes have been made). A display

of photographs, including some characteristic shots of Fr Groser, was

mounted for the occasion. Read his Church Times obituary [right - 25 March 1966], and the letter from his one-time curate Denys Giddey, protesting against his depiction by A. Tindal Hart in Some Clerical Oddities (New Horizon 1980).

Film

appearances

In 1946 John

Groser appeared, as himself (introduced as 'Father John'), in Land

of Promise, a

film about urban housing past, present and future, making a plea for

decent post-war reconstruction. It was directed by Paul Rotha for the

pioneering and left-wing Central Office of Information; the narrator

was (Sir) John Mills, with Miles Malleson, co-writer of the script, as

'The Know-All', and made extensive use of 'Isotype' graphics.

Registered users of BFI Screenonline can stream the whole fim, or

excerpts.

In 1946 John

Groser appeared, as himself (introduced as 'Father John'), in Land

of Promise, a

film about urban housing past, present and future, making a plea for

decent post-war reconstruction. It was directed by Paul Rotha for the

pioneering and left-wing Central Office of Information; the narrator

was (Sir) John Mills, with Miles Malleson, co-writer of the script, as

'The Know-All', and made extensive use of 'Isotype' graphics.

Registered users of BFI Screenonline can stream the whole fim, or

excerpts.

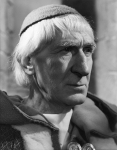

In

1949 he played the part [right] of Thomas Becket in a film of T.S. Eliot's

Murder

in the Cathedral, directed

by George Hoellering, alongside Mark

Dignam, Michael Aldridge, Leo McKern and Paul Rogers, with Eliot

himself as the Fourth Tempter. (His son Michael was Third Priest.) Hoellering wanted someone

with

spiritual authority, rather than a known actor, to play the part.

Groser let his hair grow long, rather than wear a wig, and entered

wholeheartedly into the experience; its theme of spiritual defiance

of temporal authority was dear to his heart. The film was shown in 1952

and received mixed reviews

(here

is one from the New

York Times); it was never on general

release, perhaps because of its length (over three hours). However, Stephen Brown reported its welcome release on DVD, in Church Times (29 January 2016). He gave a talk about his role to the School Association of St George-in-the-East School in Cable Street (or which for many years he was a governor).

The

John

Groser Memorial Trust was set up to help young people in

Tower

Hamlets to broaden their education by travel and voluntary service

overseas.

His papers (including some collected by Dorothy Halsall, a

parish worker at St

George's and then a colleague at the Royal Foundation of St Katharine)

are held at Lambeth

Palace Library [MSS

3428-35] and cover a wide range of topics.

Here are some comments from a version of Fr Ken Leech's entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography:

| ... Groser was profoundly influenced by Noël and the Catholic Crusade, and

the Stepney chapter of the crusade was based at Watney Street. Like

Noël, he saw the importance of festivity, of colour, music, and

dancing, in the creation of a Christian social consciousness. The

Watney Street church was an urban representation of what Thaxted was

struggling to manifest in the countryside, with joyful festivals,

folk-dancing, and processions. Here too was a democratic Christian

community, and a strong sense of the liturgy as a sacramental

prefiguring of a liberated world ... [At the Royal Foundation of St Katharine] supported by colleagues such as Ethel Upton and Dorothy Halsall, he made St Katharine's a centre for Christian discourse, and a power-house of debate and discussion about the future of east London. Here dockers and trade unionists, Christians and Jews, elderly people, and a wide range of social and political groups would meet, making the centre a kind of early ‘think-tank’ and centre of commitment to the health and welfare of the East End ... Politically Groser was one of the first generation of clergy to take Marxism and class-struggle politics seriously. He saw the racial dimensions of Mussolini's fascism at an early stage. Some claimed that he never came to terms with the post-war political settlement in Britain and was more at home amid struggle. Certainly it is his work in the 1930s and 1940s which is most remembered. Theologically, Groser was a traditional Catholic Christian. He saw God, and orthodox faith in God, as subversive. In a sermon at St Paul's Cathedral in 1934 he claimed that nothing but the religion of the Incarnation fearlessly taught and worked out in practice in a new social ethic can save the situation (Halsall). His commitment was to a ‘rebel church’. Yet one of the best summaries of his significance came from the former chief rabbi Sir Israel Brodie. Groser, he said, embodied the characteristics of the saint, with his Amos-like indignation at the grinding of the faces of the poor and his desire for radical social change (Brill, 102). Groser was undoubtedly one of the most significant Christian socialist figures in twentieth-century Britain. Hannen Swaffer, writing in the Daily Herald in 1936, said that he was the best-known priest in the East End of London (19 Oct 1936). Yet he figures hardly at all in the histories of Christian socialism, with the exception of the studies by Chris Bryant and Alan Wilkinson, and he is ignored in lives of George Lansbury and other political figures in East London on whom he had an important influence. He wrote only one book. Yet the impact of Groser, not only on the Church of England and the labour movement, but also, through the Student Christian Movement and numerous student missions, on the wider Christian community, and, locally, on struggles around housing, fascism, and the care of the elderly, was enormous ... |

| ...Michael Groser (1918–2009), sculptor and musician,

was born on 1 October 1918 at the vicarage, St Winnow, Cornwall. He was

educated at Mercers School, Holborn, London, and the University of

Leeds, where he was awarded first-class honours in English. He began to

train for the priesthood at the College of the Resurrection at

Mirfield, but left when he realized he did not have a vocation. During

the Second World War, as a conscientious objector, he worked in a West

Yorkshire coal mine, living with a miner's family: sketches he made

were later used to illustrate E. R. Manley's Meet the Miner (1947). He

also studied sculpture part-time at Leeds School of Art. Later in the

war he moved to London and worked in a pacifist service unit, helping

people who had been bombed out of their homes. After the war he studied

sculpture at St Martin's School of Art, where he was taught by Leon

Underwood, earning a living by singing as a lay vicar in the choir of

Westminster Abbey (1948–9) and vicar choral at St Paul's Cathedral

(1950–55). He also appeared as Third Priest in the film of Murder in

the Cathedral (1951), in which his father was cast as Becket. On 16

July 1951 he married Eileen Jean Harris (b. 1930), daughter of Percival

Edward Harris, steelworker; they had one son and three daughters. In 1955 Michael Groser was invited to become an alto lay clerk at New College, Oxford. He sang there until 1982, while building up his career as a sculptor. He worked mainly in and around Oxford: perhaps the most famous of his sculptures were the carved heads representing the Seven Virtues and the Seven Deadly Sins on the Bell Tower in New College. He also made many stone carvings at Magdalen College, including caricatures of members of the company responsible for the restoration of the tower; at All Souls College; on the tower of the church of St Peter in the East, which was restored and turned into the library for St Edmund Hall; and Queen's College, where he replaced the seventeenth-century carvings in the tympanum over the entrance to the North Quad. In all of these he displayed his imagination and sense of humour. At the Norman church of St Mary's in Iffley, Oxford, he carved animals and angels on the tower, and fantastic heads on the doorway, and his ‘Jacob and the Angel’ is in the church of St Michael and All Angels in New Marston, Oxford. He also made the huge cross of Christ in Majesty (1960) for the chapel of the Royal Foundation of St Katharine's, Limehouse, carved out of Burmese teak, his only major work in wood. He was an accomplished viol player: musicians and musical instruments were among his favourite subjects for his carvings. In 2004 he and his wife moved to Ballydehob, co. Cork, Ireland, to be nearer to their children. He died on 23 September 2009, aged 90, in Bantry General Hospital, of a gastrointestinal haemorrhage. |

| Gargoyles

and grotesques glare, grimace and grin from the hallowed buildings of

this old university town like a horde of uneasy spirits trapped forever

in stone. Hundreds, even thousands, of these twisted faces and writhing

figures punctuate the collegiate façades like footnotes to a long

architectural thesis. They line the walls of Balliol and All Souls and

Brasenose and Christ Church and Magdalen and New College - weathering

galleries of wild things and weird beasties. They all seem very old.

Oxford University has its roots in medieval Christianity. The oldest

buildings date from the 14th century. And these strange and often

brutally ugly stone creatures may be survivors of even earlier

pre-Christian eras, pagan images recruited to guard the very religion that subdued them, in the words of John Blackwood, the most diligent chronicler of Oxford's grotesques and gargoyles. But hundreds are not ancient at all but quite modern, some even vaguely cubist. They come from the hands of Michael Groser, a friendly but reserved and unprepossessing sculptor and stone carver, now 75 and still hard at work cutting these fearsome and fantastic figures. His skill was needed after the original carvings eroded, succumbing not so much to age as to 20th-century pollution. His figures are not exactly replacements in that they do not generally reproduce the earlier grotesques. While he has literally left his mark on the stones of Oxford in a way few other people have, he remains almost as anonymous as his medieval forebears. His carvings are unsigned, except for the marks of his chisel. People very often think my carvings are medieval, he says. The other day, a friend of mine saw some copies being sold in an Oxford market and he said: 'Have you got permission to do these? The copyright is private.' 'Oh, no, but they're very old', the dealer said. Such 'reproductions' annoy him: They very often copy them in a very amateurish way. And I feel ashamed anybody should think I've carved things like that. His carvings, he says, are now weathered and dirty so they fit in with the buildings. But he doesn't think that should cause confusion. Although I imagine to anybody who really knows much about the history of carving it would be obvious mine are 20th century and not 14th century. But they're not all that different. In Mr. Groser's definition, a grotesque is a carving of a creature distorted in some way to make it more expressive, a term he uses often. A grotesque might be an animal head or a human head or both, or something monstrous, mythological or demonic. Mr. Groser has carved two that are caricatures of former President Ronald Reagan. Usually a grotesque head has a back to it which is being built into the building behind, he says. A gargoyle is simply a grotesque with a drain pipe, or in olden days a gutter, which makes it a water spout. Grotesques flourished in the Middle Ages when they were a kind of signature of the Gothic stone carvers who cut them, often sly jokes aimed at the churchmen or priors or scholastics who hired them. Some are ribald, some just vulgar: bare butts or people picking their noses. Mr. Groser has carved dung beetles rolling their dung balls. Medieval stone carvers recorded disease and deformity in monstrously distorted stone images. Evil spirits snapping and clawing at tormented faces depict the fears and anguish and perhaps the mental illnesses of the Middle Ages. I don't think new buildings very often have that sort of thing on them, Mr. Groser says. For one thing it's expensive. No doubt in past years when labor was cheap and when there were really rich patrons who could afford these things - and if they reckoned it would get them a place in heaven to build a splendid church -- then they could do these things. Mr. Groser came to Oxford 45 years ago. He's a pacifist and conscientious objector who spent World War II as a coal miner near Leeds. I enjoyed the work, he says, but I don't know that I'd want to be a miner all my life. He had time to enroll at Leeds College to learn sculpture. He also studied later at St. Martin's College of Art in London. During his first years in Oxford, he supported himself and his wife singing countertenor in the New College choir. Throughout his life he has followed twin careers of sculpting and singing. A very satisfying life, he says. When he got his first commission to do grotesques, he sketched copies of 14th-century carvings as working drawings. They weren't successful at all, he says. So I did some drawings just from my own imagination and they were accepted. After that, on nearly all the jobs I did in Oxford I was given a free hand and I just invented. I didn't try to do a pastiche of old carvings. I just carved freely. He did a series of carvings for Balliol which represented the benefactors of the college. But he didn't have any models, pictures or anything to work from. I looked up the names of various people who were benefactors and invented faces for them, he says. In fact, for one 17th-century divine who gave lands or property or something, I put my own father's head. He was a parson himself. He was appropriate. The work of carving grotesques will go on, but not very many will be carved in Oxford for the next 500 years or so - depending on the amount of air pollution. In Oxford, there's not much opportunity anymore, Mr. Groser says. All the work's been done. And he did most of it. |