Tobacco Dock (and other specialist warehouses)

When

the docks were built - left, from church tower looking south - they fell between the parishes of St

George-in-the-East and St John Wapping, but were then included within

the new parishes of St Paul Dock Street (now part of this parish) and

St Peter London Dock (one of our 'daughter churches' and now

joined with St John Wapping, whose church has gone). The current

boundary now runs along East

Smithfield and Pennington Street, so that almost all the former docks

area falls within St Peter's parish, apart from some buildings along

The Highway and the vacant lot north of Tobacco Dock. See here for details of wool warehouses in the parish.

When

the docks were built - left, from church tower looking south - they fell between the parishes of St

George-in-the-East and St John Wapping, but were then included within

the new parishes of St Paul Dock Street (now part of this parish) and

St Peter London Dock (one of our 'daughter churches' and now

joined with St John Wapping, whose church has gone). The current

boundary now runs along East

Smithfield and Pennington Street, so that almost all the former docks

area falls within St Peter's parish, apart from some buildings along

The Highway and the vacant lot north of Tobacco Dock. See here for details of wool warehouses in the parish.

London and St Katharine's Docks [see also Harry Jones' colourful 1875 account here, which describes further features, such as the army of 300 cats maintained for vermin control, and the indigo trade]

| ...black with coal, blue with indigo, brown with hides, white with

flour; stained with purple wine – or brown with tobacco!... chapter 3, 'The Docks', in Blanchard Jerrold London - A Pilgrimage, with famous illustrations by Gustave Doré (1872) - republished with an introduction by Peter Ackroyd, Anthem Press 2005 |

The West India Docks were the first to be opened (1800-02), followed shortly by the massive London Docks

complex,

begun on the marshes of Wapping in 1801 and opened for business four

years later; the Scot John Rennie was the chief engineer. The tobacco warehouses formed part of this. The initial cost

was £4m. The massive wall alone, enclosing over 70 acres of buildings,

quays and jetties, cost £65,000 - defence was a key factor, because

piracy was rampant. In 1800 professional bandits such as the River

Pirates, the Light Horsemen,

the Heavy Horseman and the Mudlarks, each with their own techniques and

working with the connivance of corrupt crews, stole £800,000 of

goods from the open river. The

western dock covered 20 acres

of water, the eastern dock 7 acres, and between them was a dedicated

1-acre tobacco dock. There were two entrances from the Thames, at

Wapping Old Stairs and (less used) Hermitage. To this was added

Shadwell Dock in 1831, with an additional eastern entrance from the

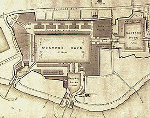

Thames, increasing the overall area of the Docks to over 90 acres. [1831 map of the original site, left, by Henry Palmer]. The street entrance was on The Highway, opposite Ensign Street.

The West India Docks were the first to be opened (1800-02), followed shortly by the massive London Docks

complex,

begun on the marshes of Wapping in 1801 and opened for business four

years later; the Scot John Rennie was the chief engineer. The tobacco warehouses formed part of this. The initial cost

was £4m. The massive wall alone, enclosing over 70 acres of buildings,

quays and jetties, cost £65,000 - defence was a key factor, because

piracy was rampant. In 1800 professional bandits such as the River

Pirates, the Light Horsemen,

the Heavy Horseman and the Mudlarks, each with their own techniques and

working with the connivance of corrupt crews, stole £800,000 of

goods from the open river. The

western dock covered 20 acres

of water, the eastern dock 7 acres, and between them was a dedicated

1-acre tobacco dock. There were two entrances from the Thames, at

Wapping Old Stairs and (less used) Hermitage. To this was added

Shadwell Dock in 1831, with an additional eastern entrance from the

Thames, increasing the overall area of the Docks to over 90 acres. [1831 map of the original site, left, by Henry Palmer]. The street entrance was on The Highway, opposite Ensign Street.

St

Katharine's Docks, a 24-acre site between the Tower and London Docks,

was begun in 1824 (with Thomas Telford as the chief engineer) and opened in 1828, at a cost of over £2m. This

involved the 'happy' removal (as one contemporary commentator put it)

of the old Hospital and Collegiate Church of St. Katharine, and 1250

slum houses accommodating 12,000 people (and see here for the former workhouse on the site). However, this had the distinctly

unhappy consequence of breaking the link between the royal foundation

of St Katharine's and the East End, first established by Queen

Matilda in 1147 – together with considerable charitable endowments,

which were only partly compensated for by new arrangements. (Map right from 1872.] The

foundation moved to Regent's Park and became a middle-class

almshouse. Later in the 19th century local clergy pressed for the

return of the foundation and its funds to the East End, but this did

not come about until after the Second World War when the Royal

Foundation of St Katharine's was re-established on the blitzed site of St James Ratcliff

church and vicarage (with the approval of Queen Mary, the Patron at that time), with Fr Groser,

formerly Rector of this

parish, as its first Master, and Olive Wagstaff, a member of our

congregation, as a member of the lay community based there until it was

supplanted. The story is told in more detail here. In a further twist, the Danish Church

- which had once been in Wellclose Square - took over the vacated

church of St Katharine in Regent's Park in 1952 and remains based there.

St

Katharine's Docks, a 24-acre site between the Tower and London Docks,

was begun in 1824 (with Thomas Telford as the chief engineer) and opened in 1828, at a cost of over £2m. This

involved the 'happy' removal (as one contemporary commentator put it)

of the old Hospital and Collegiate Church of St. Katharine, and 1250

slum houses accommodating 12,000 people (and see here for the former workhouse on the site). However, this had the distinctly

unhappy consequence of breaking the link between the royal foundation

of St Katharine's and the East End, first established by Queen

Matilda in 1147 – together with considerable charitable endowments,

which were only partly compensated for by new arrangements. (Map right from 1872.] The

foundation moved to Regent's Park and became a middle-class

almshouse. Later in the 19th century local clergy pressed for the

return of the foundation and its funds to the East End, but this did

not come about until after the Second World War when the Royal

Foundation of St Katharine's was re-established on the blitzed site of St James Ratcliff

church and vicarage (with the approval of Queen Mary, the Patron at that time), with Fr Groser,

formerly Rector of this

parish, as its first Master, and Olive Wagstaff, a member of our

congregation, as a member of the lay community based there until it was

supplanted. The story is told in more detail here. In a further twist, the Danish Church

- which had once been in Wellclose Square - took over the vacated

church of St Katharine in Regent's Park in 1952 and remains based there.

St

Katharine's Dock was never a huge commercial success, and it merged

with the London Docks, with joint offices in Leadenhall Street in

1866. (The main entrance to Daniel Asher Alexander's two 1805 Customs & Excise

offices, one with upper floor extension c1840 - left - enclosed by the main dock wall, can still be seen on the

corner of East Smithfield and Thomas More Street.) Right are two views of the main dock gate, the second from 1964.

St

Katharine's Dock was never a huge commercial success, and it merged

with the London Docks, with joint offices in Leadenhall Street in

1866. (The main entrance to Daniel Asher Alexander's two 1805 Customs & Excise

offices, one with upper floor extension c1840 - left - enclosed by the main dock wall, can still be seen on the

corner of East Smithfield and Thomas More Street.) Right are two views of the main dock gate, the second from 1964.

See here

for a sequence of 19th century accounts of London and St Katharine's

Docks, complete with facts and figures and a wealth of other detail. Having been heavily bombed, St

Katharine's Dock was the first part of

the area to be redeveloped for housing and leisure - the site was sold

to the Greater London Council for £1.7m and Taylor Woodrow won the

contract for the work [right - 1975, 1976 & 1977]. One of the few remaining buildings is...

See here

for a sequence of 19th century accounts of London and St Katharine's

Docks, complete with facts and figures and a wealth of other detail. Having been heavily bombed, St

Katharine's Dock was the first part of

the area to be redeveloped for housing and leisure - the site was sold

to the Greater London Council for £1.7m and Taylor Woodrow won the

contract for the work [right - 1975, 1976 & 1977]. One of the few remaining buildings is...

Ivory House,

at the centre of the St Katharine's site, a fine Italiante building

with a clock tower designed in 1854 by George Aitchison (1792-1861,

father and trainer of a more famous architect son). Hither were

brought, in a shameful 'colonial carnage' from Kenya and Tanganyika,

200 tons of elephant, hippopotamus and walrus ivory each year (Harry Jones writing in 1875 mentions an accumulation of tusks brought in by Livingstone which sold for £70,000),

sword-fish weapons, and even mammoth tusks from Siberia. Viewing

required a special permit. Port was stored in the cellars of the

building. It is now converted

into apartments [interior view right].

Ivory House,

at the centre of the St Katharine's site, a fine Italiante building

with a clock tower designed in 1854 by George Aitchison (1792-1861,

father and trainer of a more famous architect son). Hither were

brought, in a shameful 'colonial carnage' from Kenya and Tanganyika,

200 tons of elephant, hippopotamus and walrus ivory each year (Harry Jones writing in 1875 mentions an accumulation of tusks brought in by Livingstone which sold for £70,000),

sword-fish weapons, and even mammoth tusks from Siberia. Viewing

required a special permit. Port was stored in the cellars of the

building. It is now converted

into apartments [interior view right].

Within the former London Docks complex, on the south side of Pennington Street, the 280m-long Rum Warehouse (which was also used for other merchandise) survives. [Right - image of c1896.] It has been much-adapted - latterly during News International's occupation, when it housed The Times'

archives and library and a range of offices and technical services;

most of the original wooden roof trusses have gone, it has a metal

rather than a slate roof, and many of the vaults have been bricked in;

but it is a handsome building, grade 2 listed, and the developers who

recently acquired the site regard it as full of potential for

restoration and development, particularly if windows, lightwells and

doors can be re-opened to give northern access to the site, and present

a less forbidding aspect.

Within the former London Docks complex, on the south side of Pennington Street, the 280m-long Rum Warehouse (which was also used for other merchandise) survives. [Right - image of c1896.] It has been much-adapted - latterly during News International's occupation, when it housed The Times'

archives and library and a range of offices and technical services;

most of the original wooden roof trusses have gone, it has a metal

rather than a slate roof, and many of the vaults have been bricked in;

but it is a handsome building, grade 2 listed, and the developers who

recently acquired the site regard it as full of potential for

restoration and development, particularly if windows, lightwells and

doors can be re-opened to give northern access to the site, and present

a less forbidding aspect.Importing tobacco

Tobacco was introduced from the new colony of Virginia in the early

17th century and became popular, for smoking, chewing and sniffing

(snuff). Successive governments were keen to raise revenue from it, and

by the early 19th century the duty paid ran into millions. It was

shipped from America in 350-ton vessels, packed into large hogsheads of 1,200lb

each, and stored in bonded warehouses until the duty was paid. Pictured right - dock traffic on Whitechapel High Street 1899.

Tobacco was introduced from the new colony of Virginia in the early

17th century and became popular, for smoking, chewing and sniffing

(snuff). Successive governments were keen to raise revenue from it, and

by the early 19th century the duty paid ran into millions. It was

shipped from America in 350-ton vessels, packed into large hogsheads of 1,200lb

each, and stored in bonded warehouses until the duty was paid. Pictured right - dock traffic on Whitechapel High Street 1899.

The

Great Tobacco Warehouse (later known as the Queen's Warehouse) off

Pennington Street, at the centre of the London Docks complex, was built

between 1811-14, designed

by David Asher Alexander,

architect and surveyor to Trinity House. (Alexander also designed the

houses at Wapping Pierhead, and further afield Dartmoor Prison - where

his applied his experience in creating a fortress site - and the

Old Light at Lundy.) He

used the latest technology to create an elegant series of parallel

glazed roofs with timber queen-post trusses, supported every 54' by

slender cast iron columns with two scarf joints in each tie member.

Cast iron raking struts (bent to follow compression forces - another

innovative feature) supported every other roof truss and at right

angles Y-form struts carried the timber bolster of the roof's continuous

valley gutter, with a hollow column acting as a rainwater pipe in each

third bay.

The

tobacco warehouses were immense,

covering nearly 5 acres (21,000 square metres) and capable of storing

24,000 hogsheads, with a value of £4.8m in the 1840s. The main

warehouse was 762' long and 160' wide, equally divided by a partition

wall with double iron doors. A smaller warehouse, for fine tobacco,

was 250' by 200', and there was a cigar floor, capable of holding 1500

chests. The

hogsheads were piled two high in long ranges intersected by passages

and alleys,

with spaces between for Customs officers, who managed its operations:

the premises were rented by the government, at £14,000 a year. A massive exterior brick wall defended the

site to the north (Pennington Street) and east (Old Gravel, now Wapping, Lane): theft was always a problem.

The Queen's Pipe

| Near the north-east corner of the Queen's Warehouse, a guide-post, inscribed 'To the Kiln', directs you to 'the Queen's Pipe', or chimney of the furnace; on the door of the latter and of the room are painted the crown-royal and VR. In this kiln are burnt all such goods as do not fetch the amount of their duties and the Customs' charges: tea, having once set the chimney of the kiln on fire, is rarely burnt; and the wine and spirits are emptied into the Docks. The huge mass of fire in the furnace is fed night and day with condemned goods: on one occasion, 900 Austrian mutton-hams were burnt; on another, 45,000 pairs of French gloves; and silks and satins, tobacco and cigars, are here consumed in vast quantities: the ashes being sold by the ton as manure, for killing insects, and to soap-boilers and chemical manufacturers. Nails and other pieces of iron, sifted from the ashes, are prized for their toughness in making gun-barrels; gold and silver, the remains of plate, watches, and jewellery thrown into the furnace, are also found in the ashes. |

Cigar making Cigar makers –

many of whom were Dutch –

worked from 8am to

7pm, or with overtime up to 11pm, with half an hour for lunch and a

half day on Saturday; they earned between 4/- and 14/- a week. They

worked speedily, spreading a leaf of tobacco and making gashes in it,

then taking fragments of tobacco leaf and rolling it up, cutting it

against a guide to a given length and finally taking a narrow strip of

leaf, rolling the cigar into a spiral and twisting it at one end. In due course women were employed in this work (see here, for example).

Cigar makers –

many of whom were Dutch –

worked from 8am to

7pm, or with overtime up to 11pm, with half an hour for lunch and a

half day on Saturday; they earned between 4/- and 14/- a week. They

worked speedily, spreading a leaf of tobacco and making gashes in it,

then taking fragments of tobacco leaf and rolling it up, cutting it

against a guide to a given length and finally taking a narrow strip of

leaf, rolling the cigar into a spiral and twisting it at one end. In due course women were employed in this work (see here, for example).

In

the 1860s, before the arrival of Polish and other Eastern European Jews

who worked in the the rag trade, the tobacco industry was the chief

employer of Jewish immigrants in the East End. See Israel Sangwill's 1892 novel Children of the Ghetto (p14) for a description of the 'Dutch Tenters' (the district in Spitalfields where most Dutch Jewry lived).

Wines & Spirits

The vaults beneath, with chamfered granite columns under finely-executed brick groins, connected with a 20 acre

'subterranean city' for the storage of wines and spirits, where they could mature at a stable temperature of 60° – so the

pungent aroma of tobacco was mixed with that of wine. There was storage

for 8m gallons of wine. On 30 June1849 the Dock contained 14,783 pipes

of port; 13,107 hogsheads of sherry; 64 pipes of French wine; 796 pipes

of Cap wine; 7607 cases of wine, containing 19,140 dozen; 10,113

hogsheads of brandy; and 3642 pipes of rum. The London Dock Company

issued permits to visit the vaults (ladies are not admitted after 1pm),

and wine merchants provided visitors with 'tasting orders' to sample

wines and spirits. Later,

from the 1860s, the ground floor of the warehouse was predominantly

used for wool, furs and skins – hence the name 'Skin Floor' – and cork

and molasses. Only four acres of these vaults survive.

The vaults beneath, with chamfered granite columns under finely-executed brick groins, connected with a 20 acre

'subterranean city' for the storage of wines and spirits, where they could mature at a stable temperature of 60° – so the

pungent aroma of tobacco was mixed with that of wine. There was storage

for 8m gallons of wine. On 30 June1849 the Dock contained 14,783 pipes

of port; 13,107 hogsheads of sherry; 64 pipes of French wine; 796 pipes

of Cap wine; 7607 cases of wine, containing 19,140 dozen; 10,113

hogsheads of brandy; and 3642 pipes of rum. The London Dock Company

issued permits to visit the vaults (ladies are not admitted after 1pm),

and wine merchants provided visitors with 'tasting orders' to sample

wines and spirits. Later,

from the 1860s, the ground floor of the warehouse was predominantly

used for wool, furs and skins – hence the name 'Skin Floor' – and cork

and molasses. Only four acres of these vaults survive.

The Covent Garden of the East End?

In

1969 the Docks finally closed to shipping and the land became

derelict. By the 1980s only the Skin Floor warehouse, with six bays

totalling 80,000 square feet – two-fifths of

the original tobacco complex – was standing; it was a Grade 1 listed

building. In consort with the London Docklands Development Corporation

who owned the site, Brian Jackson and Lawrie Cohen conceived a shopping

centre with specialist outlets as well as high

street names, and other tourist attractions, to rival Covent Garden

(and three times its size, with 160,000 square feet of lettable

accomodation for 50+ tenants). It was hoped that this would attract

wealthy people to

live and shop in the area, and create 800 jobs, 75% of which might go

to local people. The architect was the postmodernist (now Sir) Terry Farrell,

and the engineer Ove Arup. Honouring the engineering achievement of

the past, they

carefully restored what remained of the original structure (dismantling

a whole bay on the west side and re-erecting it on the east, to

preserve it) and within it created unapologetically contemporary

walkways with

glass, steel and cast-iron façades for the shops. Fire regulations,

requiring one hour's fire resistance, presented a difficulty with the

timberwork of the roof: Farrell resisted thick mastic fire-retarding paint

because it would have blurred the sections, and a thin intumescent

film, carefully monitored and maintained, was eventually agreed: see

further David Pearce Conservation Today (Routledge 1989). The total cost was reported

as £47m, though some claim it was less.

In

1969 the Docks finally closed to shipping and the land became

derelict. By the 1980s only the Skin Floor warehouse, with six bays

totalling 80,000 square feet – two-fifths of

the original tobacco complex – was standing; it was a Grade 1 listed

building. In consort with the London Docklands Development Corporation

who owned the site, Brian Jackson and Lawrie Cohen conceived a shopping

centre with specialist outlets as well as high

street names, and other tourist attractions, to rival Covent Garden

(and three times its size, with 160,000 square feet of lettable

accomodation for 50+ tenants). It was hoped that this would attract

wealthy people to

live and shop in the area, and create 800 jobs, 75% of which might go

to local people. The architect was the postmodernist (now Sir) Terry Farrell,

and the engineer Ove Arup. Honouring the engineering achievement of

the past, they

carefully restored what remained of the original structure (dismantling

a whole bay on the west side and re-erecting it on the east, to

preserve it) and within it created unapologetically contemporary

walkways with

glass, steel and cast-iron façades for the shops. Fire regulations,

requiring one hour's fire resistance, presented a difficulty with the

timberwork of the roof: Farrell resisted thick mastic fire-retarding paint

because it would have blurred the sections, and a thin intumescent

film, carefully monitored and maintained, was eventually agreed: see

further David Pearce Conservation Today (Routledge 1989). The total cost was reported

as £47m, though some claim it was less.

The new-look Tobacco Dock opened in 1989 – an inauspicious time, as

recession was soon to bite. Within a year of opening some shops were

closing down because they had too little business and rents were too

high. By the middle of the decade all the chain stores had gone. The

dream had failed: the area was not a recognised tourist or retail

venue, and public transport connections were inadequate (they

have now improved since the East London Line became part of London

Overground): see further C.M. Hall & S. Page The Geography

of Tourism and Recreation (Routledge 1999). The development went into receivership, leaving only one outlet, the

Frank & Stein sandwich shop, which continued to serve the lunchtime

trade. But the site is still maintained, with cleaners, security staff

and (it is said) even a kestrel to chase away pigeons. The Rough Guide to London describes the development as 'kitsch', and comments tartly The locals would probably prefer another superstore, while the rest of London wouldn't dream of coming out here.

The new-look Tobacco Dock opened in 1989 – an inauspicious time, as

recession was soon to bite. Within a year of opening some shops were

closing down because they had too little business and rents were too

high. By the middle of the decade all the chain stores had gone. The

dream had failed: the area was not a recognised tourist or retail

venue, and public transport connections were inadequate (they

have now improved since the East London Line became part of London

Overground): see further C.M. Hall & S. Page The Geography

of Tourism and Recreation (Routledge 1999). The development went into receivership, leaving only one outlet, the

Frank & Stein sandwich shop, which continued to serve the lunchtime

trade. But the site is still maintained, with cleaners, security staff

and (it is said) even a kestrel to chase away pigeons. The Rough Guide to London describes the development as 'kitsch', and comments tartly The locals would probably prefer another superstore, while the rest of London wouldn't dream of coming out here.

See here

for details of two fibreglass statues included inside - first left shows their location. Outside, two

replica ships are moored on the ornamental canal (all that is left

of the dock basin). The Three Sisters [second left] is a copy of a 330

ton ship built at Blackwall Yard in 1788, which traded until 1854, taking manufactured goods

to the East & West Indies and returned with tobacco & spices. The Sea Lark [right] is a copy of an 18th century American built schooner,

which ran the blockade and was captured by the Admiralty during the Anglo-American War in

1812-14. When open, the former told the story of piracy and the latter showcased Robert Louis Stevenson's Kidnapped.

See here

for details of two fibreglass statues included inside - first left shows their location. Outside, two

replica ships are moored on the ornamental canal (all that is left

of the dock basin). The Three Sisters [second left] is a copy of a 330

ton ship built at Blackwall Yard in 1788, which traded until 1854, taking manufactured goods

to the East & West Indies and returned with tobacco & spices. The Sea Lark [right] is a copy of an 18th century American built schooner,

which ran the blockade and was captured by the Admiralty during the Anglo-American War in

1812-14. When open, the former told the story of piracy and the latter showcased Robert Louis Stevenson's Kidnapped.

In

1996 consent was given to Smith Lance Larcade & Bechtol to create a

cinema multiplex and car park on the adjacent lot, between Tobacco Dock

and The Highway, and in 1998 consent was acquired to link this to

Tobacco Dock by a

footbridge. In 1999 consent was refused to SLLB for a seven-storey

shopping development, and in this year the site was acquired by Messila

House, the UK representative agency of the Kuwaiti Commercial Real

Estate Centre (established in 1973 by the late Mubarak Abdul Aziz al

Hassawi; it is said that the unanimous consent of over 30 family

members is needed for any new scheme). Permission for a similar scheme

was again refused in 2007.

Meanwhile, In 2003 English Heritage placed Tobacco Dock, a Grade I

listed building, on

their Heritage at Risk

register. Concern had mounted, both on heritage and regeneration

grounds, that this important structure was left idle, and local people

and others continue to press for a viable scheme that will bring

benefit to the area. See here for the latest proposals for the adjacent site on The Highway.

The

building was sporadically used for corporate events, such as the

Vodafone and ABN AMRO annual staff party in 2005, and various

post-première film parties. In 2004 it was used as the studios of the

Channel 4 reality tv show Shattered. In a slight anachronism, an

episode of the BBC1 drama Ashes to Ashes (set in 1981) was filmed

here. One regular annual event held at Tobacco Dock is the

International London Tattoo Convention held

over a weekend each September, which draws over 20,000 people with a

startling range

of body decorations. After three years at the Old Truman Brewery in

Brick Lane, it needed more space and moved here in 2007. Most recently, during the

2012 London Olympics, it was brought into action at short notice to

house large numbers of soldiers [right], drafted in as a crisis measure

as security guards in the wake of the G4S debacle. Many

of them were only just back from

Afghanistan and were not unreasonably looking forward to some leave.

Since then, the site has been opened more often for a range of events.

The

building was sporadically used for corporate events, such as the

Vodafone and ABN AMRO annual staff party in 2005, and various

post-première film parties. In 2004 it was used as the studios of the

Channel 4 reality tv show Shattered. In a slight anachronism, an

episode of the BBC1 drama Ashes to Ashes (set in 1981) was filmed

here. One regular annual event held at Tobacco Dock is the

International London Tattoo Convention held

over a weekend each September, which draws over 20,000 people with a

startling range

of body decorations. After three years at the Old Truman Brewery in

Brick Lane, it needed more space and moved here in 2007. Most recently, during the

2012 London Olympics, it was brought into action at short notice to

house large numbers of soldiers [right], drafted in as a crisis measure

as security guards in the wake of the G4S debacle. Many

of them were only just back from

Afghanistan and were not unreasonably looking forward to some leave.

Since then, the site has been opened more often for a range of events.