Local judges (2): His Honour Judge Francis Henry Bacon (1832-1912)

Francis Bacon was the third son of Sir James Bacon (1798-1895 - left from Vanity Fair, 8 February 1873), last of the Vice Chancellors

of the Chancery Court (the title was abolished in 1875 with the re-organisation of the

courts). Eighty years old when his son was made a County Court judge,

friends urged him to retire. See, he replied, I have my son, Francis, at the Bar, and I have to provide for him. After the appointment was assured, his friends tried again. See, they said, your son, Francis, has been made a judge. He replied, Yes, and it has made me so glad. It has taken such a great load off my mind that I feel ten years younger.

For his out-of-town house, he rented from the Earl of Craven a

picturesque 'moated grange',

Compton Beauchamp (The 'Old Manor House') in Shrivenham [then in

Berkshire]. Originally held by the baronial family of Somerly, William

de Beauchamp (ancestor of the Earls of Warwick) and his successors

became lords of the manor, and Sir Thomas Fettiplace, King's

Councillor, took it on in the early 16th century. A century later it

was rebuilt as a Tudor manor house, and had

a Palladian façade added in the 18th century. Francis continued to live

here after his father's death, until his own. (In the 1940s it was let

to the Singer Manufacturing Company heiress Daisy Fellowes.) Right are illustrations from an early edition (1897) of Country Life - from the north, showing the moat; from 1935; and today, with further additions.

Francis Bacon was the third son of Sir James Bacon (1798-1895 - left from Vanity Fair, 8 February 1873), last of the Vice Chancellors

of the Chancery Court (the title was abolished in 1875 with the re-organisation of the

courts). Eighty years old when his son was made a County Court judge,

friends urged him to retire. See, he replied, I have my son, Francis, at the Bar, and I have to provide for him. After the appointment was assured, his friends tried again. See, they said, your son, Francis, has been made a judge. He replied, Yes, and it has made me so glad. It has taken such a great load off my mind that I feel ten years younger.

For his out-of-town house, he rented from the Earl of Craven a

picturesque 'moated grange',

Compton Beauchamp (The 'Old Manor House') in Shrivenham [then in

Berkshire]. Originally held by the baronial family of Somerly, William

de Beauchamp (ancestor of the Earls of Warwick) and his successors

became lords of the manor, and Sir Thomas Fettiplace, King's

Councillor, took it on in the early 16th century. A century later it

was rebuilt as a Tudor manor house, and had

a Palladian façade added in the 18th century. Francis continued to live

here after his father's death, until his own. (In the 1940s it was let

to the Singer Manufacturing Company heiress Daisy Fellowes.) Right are illustrations from an early edition (1897) of Country Life - from the north, showing the moat; from 1935; and today, with further additions.

Francis was named after his uncle, an editor of The Times

- perhaps also with a famous namesake judge of the 17th century in mind. After Balliol College, Oxford he was called to the Bar at Lincoln's Inn

in 1856 and practised as a Chancery lawyer on the Eastern circuit, but

not extensively; he served as secretary to Vice Chancellor (later Lord Justice) Giffard and

then to his father, worked as an equity drafter and conveyancer, and was a

'revising barrister' for Middlesex - updating the register of voters,

for which purpose in 1867 he held a court in Wellclose Square

for the Tower Hamlets Borough, parish by parish. In 1878 he was

appointed by Lord Cairns to the County Court bench, as judge of both

Tower Hamlets (in Great Prescot Street) and Bloomsbury (Great Portland

Street) courts. His salary in 1891 was £1500; his London home was

initially Kensington Gardens Terrace and later 1 Lancaster Gate

Terrace, and his country home as above.

Like

his father, he did not believe in retirement; he died in office aged

79, the oldest serving judge at that time, having returned from a

temporary swap, by way of a rest, with Judge Granger of the Cornwall

circuit (succumbing to illness on his return, from which he did not

recover). He worked hard, and was noted for his frugal lunches - a

couple of biscuits and a glass of sherry - replying to a barrister who

asked that a case might not be taken before lunch, I know of no such festival.

On 10 November 1910 he beat his own record by sitting at Whitechapel

from 10am to 9.30pm, with a total of less than fifteen minutes

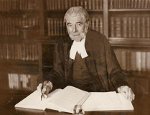

adjournment during the day - because of the volume of workmen's compensation cases. [Cartoon left from Vanity Fair 4 November 1897; photograph right 1906.]

Like

his father, he did not believe in retirement; he died in office aged

79, the oldest serving judge at that time, having returned from a

temporary swap, by way of a rest, with Judge Granger of the Cornwall

circuit (succumbing to illness on his return, from which he did not

recover). He worked hard, and was noted for his frugal lunches - a

couple of biscuits and a glass of sherry - replying to a barrister who

asked that a case might not be taken before lunch, I know of no such festival.

On 10 November 1910 he beat his own record by sitting at Whitechapel

from 10am to 9.30pm, with a total of less than fifteen minutes

adjournment during the day - because of the volume of workmen's compensation cases. [Cartoon left from Vanity Fair 4 November 1897; photograph right 1906.]

Kissing the book

The British Medical Journal ran a campaign against the unhygienic practice of kissing the New Testament when taking the oath. Section 5 of the 1888 Oaths Act

permitted the [now standard] 'Scotch form', holding the book in the raised right hand.

In 1896 the BMJ singled out Judge Bacon as one who refused

this lawful option, despite a circular from the Home Secretary:

| It appears to be exceedingly difficult to make the minor judges obey the law. Over and over again in these columns we have had occasion to refer to the flagrant illegalities committed by magistrates, coroners, and county court judges in not merely refusing to allow witnesses the right to take the oath in the new form, but in brow-beating and bullying those who make that exceedingly reasonable claim. The last incident reported in the daily press is a particularly bad case. It is stated that at the Whitechapel County Court a few days ago a witness, who was himself Scotch, strongly objected to 'kiss the Book', on the ground that it had been kissed by hundreds of people that morning, and that some of them had probably been suffering from disease. As our readers are aware, the witness has an absolute right by statute to take this ground, and he was entitled to take the oath without further discussion according to what was originally the Scottish form, that is, by holding up his right hand without kissing the Book at all. One would have supposed that the county court judge, who was Judge Bacon, would have known this very simple point of law, especially as the late Home Secretary, in consequence of numerous complaints, addressed an official circular to all judicial officers specially calling their attention to the act. It is reported, however, that what happened at Whitechapel was that the Scotch gentleman was first of all bullied by the usher, who told him he must kiss the Book, and then reprimanded by the judge, who singularly enough told him he ought to have asked to have the Book opened, and finally compelled him to kiss it in that fashion, although the witness with perfect truth remarked that that did not make it much better. We should really like to know what excuse is to be made for county court judges, and even judges of the High Court, who persist in this childish disregard of what is now a well-known matter of elementary practice; and we sincerely hope that some of our readers will absolutely refuse to kiss one of these dirty and infectious court Testaments, and will tell the judge to his face that he ought to know the Act of Parliament and to obey it. |

| We are glad to see that some progress is being made towards the abolition of the uncleanly and dangerous English practice of administering the oath by requiring a witness to 'kiss the Book'. At first many judges appeared to be unaware of the existence of the Oaths Act, 1888, and often refused to allow witnesses to be sworn in what is called the Scotch fashion prescribed by that Act. From a note in the Daily Mail of March 15th we learn that Judge Bacon, in the Bloomsbury County Court has now advanced so far as to offer to have a witness sworn in the Scotch fashion. It is true he could not forbear a sneer at a witness who had made a pretence of kissing the Book, That is too transparent, said the judge, if you have got a fad about microbes, you should say so, and I will swear you Scotch fashion. This offer marks a distinct advance, although it would have been more satisfactory had the judge set an example and carried out the law in a more gracious fashion. Possibly Judge Bacon is one of those people who have never seen a microbe through the microscope, and who have not taken the trouble to make themselves acquainted with the elementary facts of bacteriology. They are known to the man in the street, but the ignorance of judges with regard to matters of common knowledge is proverbial. The City Press is responsible for the statement that the two Testaments in the City of London Court are kissed by 30,000 persons annually, while a police-court usher is said to have stated that the covers of his New Testament had been worn smooth and well polished from the pressure of numberless lips, bearded and beardless, blooming and faded, honest and lying, foul and sweet, as some 49,760 witnesses were sworn in that court annually. There can be no question whatever about the right to be sworn in the Scotch fashion, for Section 5 of the Oaths Act1888 runs as follows: If any person to whom an oath is administered desires to swear with uplifted hand, in the form and manner in which an oath is usually administered in Scotland, he shall be permitted so to do, and the oath shall be administered to him in such form and manner without further question.”We are informed that the members of the Leyton Medical Society have agreed invariably to adopt this form, and the matter is one upon which the medical profession might very well continue to preach by example. |

On court procedure, and remarks to lawyers and witnesses

Chatty Methods on the Bench

A comment at Bloomsbury in 1907, to a batch of railway clerks - How silly you chaps are to get into debt with moneylenders - prompted this humorous piece, with a judge speaking in the slang of the day, in Punch - anonymous, but later accredited to P.G. Wodehouse and now included in an ebook Plum Punch: Crime and the Courts.

Another remark picked up in a work of fiction, by Julian Barnes in Arthur and George (2010), was his ruling that the retention of expired season tickets was illegal (B 1899).

Interpreters, and Jewish litigants

He disapproved of interpreters in court, and often pounced on litigants

on the basis of his fluency in various laguages, including Italian and

French, and the working knowledge of Yiddish which he acquired.

Over the years he made a number of forthright remarks in his court about the

veracity of certain Jewish and other foreign litigants, based on his long

experience. He was possibly less anti-semitic than others of his time and class - see below

for a comment to Isabel Fry. His engagement with

Yiddish language and culture impressed some observers and surprised

some litigants. Nevertheless, his comments caused controversy.

H.S. Lewis (himself Jewish) wrote, in The Jew in London - two essays prepared for Toynbee Hall in 1900, with introduction by Canon Samuel Barnett - p172f:

| One it sometimes tempted to despair that the bulk of the Polish immigrants have no sense of truth whatever. No more positive spectacle can be witnessed than the hearing of a summons at an East-End police court, where the parties concerned are foreign Jews. Obvious perjury on the slightest provocation is committed in case after case. The comments of Judge Bacon at the Whitechapel County Court on this fact have been severely criticised by the Jewish press. His generalizations may have been too sweeping, being based on his experience of petty litigation, where the seamy side of life is necessarily prominent. At the same time, his remarks have been based on a substantial substratum of truth. It is the experience of most visitors among the foreign poor for charitable societies, that although absolute imposture is exceptional, falsehoods with regard to the details of cases are constantly met with. |

[John Cooper Pride versus Prejudice: Jewish Doctors and Lawyers in England, 1890-1990

(2003) includes discussion (ch.6) of the treatment of Jewish litigants

in the early 20th century at Whitechapel County Court, before Judge Bacon and his successor Judge Cluer, and in the

criminal courts.]

[Interpreters remained in use: in 1945 Julius Jung, who

had offered his services as a Yiddish interpreter on a voluntary basis

to meet a continuing but decreasing need, stood down, and was thanked by the Jewish Board of Guardians.]

Women

Here is an account from the Nursing Record & Hospital World:

| Smirching the Profession (21 May 1898) At Bloomsbury County Court a lady, the proprietress of a nursing home, told Judge Bacon that she wanted to make an application. What, again? Would you not save your temper and your time by staying at home? [Smiling] I should never lose my temper with your honour. [Laughter] I want an injunction to prevent that man distraining on me. He is your landlord's agent, is he not? Yes, he has a spite against me, as you know. I only know he wants you to pay your rent. So I do when I can, but he puts the brokers in. I work very hard. I have a lot of trouble and a paralysed mother to keep. But he cannot tell his employer, 'I know this young lady is a hard-working women, she has a lot of trouble and a mother to keep, and will pay when she can.' Then I cannot have the injunction. What can I do to keep him out? Pay the rent when it is due, then you won't have the brokers. They do me a lot of harm. The nurses talk about it all over the place, and it makes my position worse than ever. They do gossip. Surely you are not going to accuse your own sex of gossiping? Do women bear tales? [Laughter] Oh, yes they do; though I am a woman myself. And certificated nurses are the very worst gossips in the world. I have had to deal with them all my life, so I know. [Laughter] Perhaps so. They have to cheer the long weary hours of their patients. So they regale them with all the little pleasant scandals they know, and when their memory fails they invent them. [Laughter] Then I can have no protection here? No, miss; I cannot help you. I am only a week beyond my time, and he puts a man in. Can you not grant an injunction if you try really hard? [Laughter] I cannot prevent your landlord exercising his legal rights. That's like the men all over. There is one law for the men and quite another for the women. Do not leave the court labouring under that delusion [Laughter]. The laws weighs no more heavily upon women than men. It is true women have not the franchise as yet, but they have every other privilege a man has — and a good many more in addition. [Laughter] [Leaving the court] It is very hard I should be persecuted like this. The journal adds tartly [though without noting that her comments were perhaps more objectionable than his] We beg to inform Judge Bacon that there is no delusion that men and women are not equal before the law. We don't want privileges, we want legal status, and the power which legal status gives for self-government. Trained nurses have no legal status. If they had the power they would take some justifiable means to prevent their profession being smirched almost daily in the police courts. |

Fashion and the rag trade

Though he never married, Judge Bacon became something of an expert on

female as well as male fashion, and would often use a tape measure to resolve dressmaking and tailoring disputes. Two examples:

| Having carefully measured every part of a costume, the following day he said The waist is 22½ inches. The expert said Not quite, so he investigated and exclaimed Why,

yesterday there was a gap here, showing a white garment, the name of

which I do not know. I give judgement in favour of the lady's tailor.

It has become a common thing for women to come to court with their

underclothing padded out to an inordinate extent to show that clothes

do not fit. The witness (who had endured the measuring unmoved) burst into tears and said You can come down and see if I am padded [W 1910]. Alphonse Lamine, of Great Portland Street, sued the wife of the famous advocate Edward Marshall Hall KC MP for eleven guineas for the making of a coat, skirt and blouse, which Mrs Hall said did not fit. Judge Bacon asked her to retire and put on the garments. As she stood on the steps of the bench, he ordered her not to talk, or to wriggle about. He measured each seam of the coat, and then directed its removal (which the usher mishandled, pulled vigorously at the sleeves). His conclusion was There are things in the making of it that will prevent the coat and skirt ever being made right. The diagonal material is cut in such a way that it can never be made to fit. He gave judgement for Mrs Hall with costs [B 1910]. |

However, he was less inclined to measure a wooden leg,

which Mr Dearness, a railway clerk, had bought for for £25, paying half on

delivery. Previously he had worn a boy's leg, which gave him much pain.

He claimed the new leg was a bad fit, despite having been altered once

or twice, but he had to keep wearing it because he had no other, and

could not afford regular replacements, and that he had been given an

assurance that it would last for seven years, which the plaintiffs

denied, saying wear and tear was unpredictable. He asked to return it

and reclaim his £13. Judge Bacon declined his offer to remove it for

inspection, yet ruled it was a good fit, and gave judgement with costs

for the plaintiff (B 1891).

He asked a woman who said she could hardly earn enough to keep her children,

He asked a woman who said she could hardly earn enough to keep her children,  A woman sued by a dressmaker said she had ordered a princesse robe [right], and had been supplied with a costume in two pieces. You might as well be out of the world as out of the fashion. But, asked counsel for the dressmaker, what's the difference between putting on a princesse robe and a dress in two portions? He replied, It's

like this - putting on your breeches and your waistcoat, and putting on

your overcoats. A princesse gown has no seam at the waist.

A woman sued by a dressmaker said she had ordered a princesse robe [right], and had been supplied with a costume in two pieces. You might as well be out of the world as out of the fashion. But, asked counsel for the dressmaker, what's the difference between putting on a princesse robe and a dress in two portions? He replied, It's

like this - putting on your breeches and your waistcoat, and putting on

your overcoats. A princesse gown has no seam at the waist.| Caution against trusting Married Ladies (1882) Lorbuck, a tailor of Mortimer Street, Cavendish Square, sued Mrs Van Dann of Park Street for £6, the cost of making a silk-lined 'Newmarket', and for £2 in exchange for a mantle. She said she was a married woman, having married at St Pancras Register Office, though she could not say exactly when. Judge Bacon: You must surely remember when you were married. She said she could not exactly remember - and that he was presently in Paris. Judge Bacon told the plaintiff that he should have sued the husband, since a wife had no right to enter into a contract by which she pledged her husband's credit. He replied that it was extremely hard that tradesmen should be treated in this manner. Judge Bacon: If tradesmen acted with a little more caution they would not meet with such losses. Judgment would be in favour of the defendant, but she must return the mantle. Defendant: Well, I will do so, but the plaintiff owes me £2, how shall I get it? Judge Bacon: I have nothing to do with that, As she left the court she threw the mantle at the plaintiff. |

| A Streatham

woman whose husband had forbidden her to pledge his credit pleaded that

an account owing to Oxford Street drapers was for 'necessaries' for

which her husband was liable. Judge Bacon: Can a stole be a necessity for a woman? Can a sunshade? Can laces and gloves at 2/6 a pair? These are all mere extravagances. Here is £2 for a woman's hat. Surely for 7/6 she could get a hat which would fascinate all the neighbourhood. All these articles are not dress, but superstructures on dress. She must have been provided with necessary dress or she would not have put on gloves. She could not have wandered about in gloves and a sunshade. She was ordered to pay the bill. (B 1905) |

| Hudson v

Sheppard (1911) Mrs. Amy Hudson (also known as Madame Martin), a teacher of voice production and singing, sued Miss Dorothy Sheppard (known as Dorothy Dayne) for £100 for breach of contract. Mrs Hudson was represented in court by Lord Tiverton, who said that the defendant had entered into a contract to take lessons from the plaintiff, and the remuneration was to be a percentage of her earnings on the stage during three years; he claimed that although the defendant was a minor, it was for her benefit, and therefore was binding. Mrs Hudson said that the defendant brought a pupil to see her with a view to studying with her; nothing was done until the pupil's mother had been consulted, but she decided this was a good offer and would be beneficial, so an agreement was signed. She attended 47 sessions, but frequently there were letters saying she could not attend, despite Mrs Hudson's readiness to give lessons; I do not know why she ceased to come. The defendant had a part, and was an understudy, in Tantalizing Tommy [a 4-act comedy of 1867 by Paul Gavault and Michael Morton]. Her voice gained in volume, and she promised to be very successful. From February 1910 to February 1911 she had earned £11, and she estimated that this would rise to between £240 and £300 in the coming years: she is a young woman of talent, and capable of earning the amount. She did not consider that the agreement was harsh or unreasonable. Mr Highmore (the defendant's lawyer) cited an 1899 judgement of Darling J to support the claim that this contract was not for the benefit of an 'infant'. But Judge Bacon disagreed. It is a case of 'no cure no pay'. Could it be urged that the contract was not for the benefit of the infant? She was not asked to sign an agreement binding her for payment for lessons. No: the plaintiff said, 'I will train you and as a result you will be able to repay me out of the earnings'. If there were no earnings there would be no remuneration. I cannot see a more honest agreement. Could there be any answer to the plaintiff's claim? The defendant gave evidence, and said that she had an engagement before she met the plaintiff. She was receiving £2 a week. Judge Bacon: Did that include matinees? Yes. It was at the Playhouse, where she was an understudy. She had previously taken part in the Shakespeare Festival with Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree. She was expecting another engagement shortly. His judgement was that there had been an agreement which was broken by the defendant. He assessed the damages on the three years' earnings at £90. As £6 9s. had been paid, there would be judgment paid by results, for £83 11s. and costs. |

Miscellaneous

He was, however, alert to the needs of those

with disabilities (while also expert in detecting malingering and

feigned sickness), as this 1910 report, shows - though, as he ruefully pointed

out in another case, workman's compensation is causing a battle of litigation, and was the reason for his mammoth session mentioned above. See a comment from his successor here.

|

Employment of a One-eyed Man (1910) Counsel asked Judge Bacon to review the circumstances of a case of distress under the Workmen's Compensation Act. The applicant, an able-bodied seaman, met with an accident on a vessel, and lost the sight of one eye. Last April, Judge Bacon was assured by evidence that the applicant could be further employed as a seaman, though he had only one eye, so he suspended the award and kept it alive by ordering a payment of one penny weekly. Mr. Abinger said the man was destitute. He had been refused work by eight shipping lines. He had walked the streets at night, and on one occasion had fell down in an exhausted condition, and was taken to an infirmary. The man said that when he applied at one ship he was told that they did not carry cripples. He walked the streets for about eight days. The Shipping Federation did not offer him any work. Judge Bacon said that at first he thought it was not possible for a seaman with one eye to do his work properly, but he made the alteration in accordance with the evidence which had been given to him that the man could be employed. He did not agree with the contention that the man had been unable to obtain employment owing to the state of labour in the Mercantile Marine. He now reviewed the circumstances, and directed that the man should receive 10s. a week, the order to be dated back to October. |

A further sample of cases from Judge Bacon's courts

| A Theatrical Bill-Poster's Squabble (B 1879) In the case of Barnett v. England a theatrical billposter, of Hadley-street, Camden Town, sued a rival billposter to recover damages over a 'station' which he claimed was his. He said he had simply brought the action in the interest of the trade, and although he only sued for nominal damages, he trusted His Honour would rule in his favour in order to deter others. He rented a 'station' in College-street, among others. The defendant had pasted his own bills and a newspaper sheet over one of the Vaudeville Theatre bills. He had no opportunity of checking these transactions without bringing the matter into court, as the defendant generally carried on his operations at night. He agreed with Judge Bacon that he could not prove any special damage, but those theatres whose bills he displayed might sue him for a breach of contract if their bills had been disfigured. Theatrical bill inspectors were very sharp in doing their duty. The defendant said he was not aware that the plaintiff's was a protected station, as he had considered it as a 'fly posting station'. He had 'shot' at the plaintiff's name, for he had done the same by him: it was one of the tricks of the trade. Judge Bacon ruled in the plaintiff's favour, awarding damages of one penny. |

Fallen on hard times (B 1891)   Mabel Cooke - Mrs Keningale Cook - theosophist, occult novelist [as Mabel Collins),

fashion writer, anti-vivisectionist campaigner and reviewer, was sued for £48 2s 10d by a firm of printers and stationers. She

said she was broke - she had lost £1,500 lent to Madame Clarisse for a

millinery business (and it was untrue, as some alleged, that she was

herself Madame Clarisse), owed £30 rent on her former home in Holland

Park and was in debt to her servant. She had just sold her third share

in the short-lived firm of Pompadour Cosmetics [1890 advertisement right],

which raised only £12 10s. Her reviewing work had dried up, and

payments were late in coming, so she was living on £4 a week. She

received very little from her publishers Ward and Downey and had

written no novels for over a year. Counsel asked But

you have written a great many works of fiction? ... Several cheap

novels? ... I suppose they are sold at railway bookstalls in large

numbers? to which she replied I know nothing about that. My publisher brings them out on his own account, and pays me a certain sum down for each book. He then asked, You have produced, among others, The Prettiest Woman in Warsaw, Through the Gates of Gold, and Ida, an Adventure in Morocco [cover right], Have you ever been in Morocco? Judge Bacon interrupted What a question to ask. It is not necessary that she should go to Morocco. Counsel continued, You go a good deal to theatres? She replied Only once since the summons was issued, and Judge Bacon, keen to show that he was a man of the world, added These newspaper people are all on the free lists.

Counsel read a paragraph from the press 'There were a number of pretty

women in the dress-circle, including Mabel Collins, wearing a green

gown with lilies upon it'. Was that grown made especially for the occasion? She replied It was a gown I had had two years, and I didn't wear lilies, so that whoever wrote that has not a very good sight. Judge Bacon ruled that she should pay £1 a week, or go to Holloway Prison. Mabel Cooke - Mrs Keningale Cook - theosophist, occult novelist [as Mabel Collins),

fashion writer, anti-vivisectionist campaigner and reviewer, was sued for £48 2s 10d by a firm of printers and stationers. She

said she was broke - she had lost £1,500 lent to Madame Clarisse for a

millinery business (and it was untrue, as some alleged, that she was

herself Madame Clarisse), owed £30 rent on her former home in Holland

Park and was in debt to her servant. She had just sold her third share

in the short-lived firm of Pompadour Cosmetics [1890 advertisement right],

which raised only £12 10s. Her reviewing work had dried up, and

payments were late in coming, so she was living on £4 a week. She

received very little from her publishers Ward and Downey and had

written no novels for over a year. Counsel asked But

you have written a great many works of fiction? ... Several cheap

novels? ... I suppose they are sold at railway bookstalls in large

numbers? to which she replied I know nothing about that. My publisher brings them out on his own account, and pays me a certain sum down for each book. He then asked, You have produced, among others, The Prettiest Woman in Warsaw, Through the Gates of Gold, and Ida, an Adventure in Morocco [cover right], Have you ever been in Morocco? Judge Bacon interrupted What a question to ask. It is not necessary that she should go to Morocco. Counsel continued, You go a good deal to theatres? She replied Only once since the summons was issued, and Judge Bacon, keen to show that he was a man of the world, added These newspaper people are all on the free lists.

Counsel read a paragraph from the press 'There were a number of pretty

women in the dress-circle, including Mabel Collins, wearing a green

gown with lilies upon it'. Was that grown made especially for the occasion? She replied It was a gown I had had two years, and I didn't wear lilies, so that whoever wrote that has not a very good sight. Judge Bacon ruled that she should pay £1 a week, or go to Holloway Prison. |

| Medical Battery Company v Jeffery (B 1892) The company sued Jeffery, a bank clerk, for £3 5s, the balance of a £5 5s payment for a Harness patent electric belt which they had supplied. He counterclaimed this sum, and the return of the £2 already paid, because he had been induced to buy it through misrepresentation, and had received no good consideration for his contract. He went to their Oxford Street office suffering from a sprain which he feared would turn into a rupture, and was referred to their 'expert', Frederick Thomas Simmons, who recommended he should wear one of their electric belts, with a suspender. It did him no good whatever, and he developed a rupture a few weeks later. The case turned on two issues: a) what had been said to Jeffreys at the time? Simmons said he never purported to be 'qualified': until taken on by the company seven years previously he had been an oriental furniture salesman (which he agreed gave him no relevant experience), but said he had studied the treatment of hernia all his life, since he was nine years old (!) He began acting as a consultant after three months with the firm, and estimated he had since dealt with 16,900 referrals, fitting trusses and dealing with hernias and sprains. In cross-examination he said that there was no absolute rupture - the internal, not not the extrernal ring, was disturbed - and that the electrical belt would decrease the pressure and give tone to the muscles. In response to Judge Bacon's questions, he said that wearing a truss at this stage would not have had the same effect and would have been positively injurious, as unlike the belt it would not have strengthened the walls of the abdomen. b) evidence as to whether the electric belt had any efficacy at all. Although tests showed that it could produce a small electrical current, they also showed that no electricity passed through the body, but only along the webbing of the belt and over the surface of the skin. Electrically these belts are useless. Judge Bacon upheld Jeffrey's counterclaim. He had been taken in the the sense that he had been persuaded to buy something utterly useless. That was not itself sufficient for him to break the contract or claim recompense, but he found that Simmons had been misrepresented to him as an expert. As for electricity, I will not enter into the merits of an electrical appliance which I do not understand. [The] evidence as to the electrical volume may be right or wrong — I do not know; but this [belt] is the thing to put on the man when he was ruptured, and the man was persuaded to buy it upon the representation that he was not ruptured. |

| Browne v Earl of Annesley (B 1893) Dr Lennox Browne sued successfully for the unpaid balance of 18 guineas on his bill for an operation performed on the Earl's son Lord Glerawley to cure his stammer. Dr Browne was recommended by Mrs Baker; he said he was a recognised authority, but had never promised a complete cure. The operation, under chloroform (for which 2 guineas were charged) only took three minutes [what form did it take?] but other surgeons gave evidence that the charge of 30 guineas was reasonable, and Judge Bacon agreed. |

A ghost story (W 1895)

A ghost story (W 1895)Ratcliff builder John Yates sued his son, a mathematical instrument maker, for recovery of possession of 80 Brook Street Ratcliff. Many years before the house was empty, claimed by no owner, and reputed to be haunted. But a Mr Besley entered and lived there with his wife and family for some time; after his death his widow married the plaintiff's father. When he in turn died, his eldest son Matthew Yates took possession but, being ordered by the Vestry to execute repairs, gave up possession to the plaintiff, his brother. His son then asked to live there and he consented, but kept an office there. In 1894 the plaintiff fell 48ft off a ladder, and spent many months in hospital. The Vestry intended buying the house, under their slum clearance powers; the son claimed it as his own and denied his father's title. The defendant produced a notebook, which Judge Bacon examined. Judge Bacon: Where did you get this definition of 'mesne profits'? Defendant: Out of 'Nuttalls'. [a standard dictionary - new edition 1894 - right] Judge Bacon: And 'messuage'? Defendant: From 'Nuttalls' too. Judge Bacon said be believed the defendant had been coached by someone with dangerously little knowledge of law to concoct a fraudulent claim against his father. The plaintiff's title was very loose, but held good against the son, and judgement would be given for him with costs. |

| A spoiled cake (W 1895) Hannah Solomon claimed 5s 6d for the value of a cake and baking dish spoiled by the defendant, Isaac Weidel, baker and confectioner of Mansel-street, E. On the last Friday in December she made a cake, which she took over to Weidel to be baked. When it was returned to her it was burnt to a cinder. She asked him what he was going to do for her, and he offered her 4lb of flour, but as she had used 8lb she was not satisfied. Judge Bacon: It was not a very light cake. Only one packet of baking powder? Plaintiff: Oh, yes, it was. It is like a brick now. It would do to scrub a hearthstone. But when I made the cake I put in yeast as well, 4oz. of it. Judge Bacon: Baking powder and yeast both? That would spoil any cake? Plaintiff: Not at all. I always use both. Judge Bacon: Nonsense. Plaintiff: It ain't nonsense. I have made cakes for the last 14 years, and think I ought to know. What on earth do men know about these things? [He was probably right: baking powder acts quickly, and would inhibit the slower action of yeast.] Weisel said that when the cake was brought to him he told her he was going out and he had no man in his bakehouse. He told her that if he took it in she was to look after it. Plaintiff: That's not true. I went to the Cambridge that night with my daughter's young man. Defendant: Next morning, when she came for the cake and found it burned, she made a great disturbance. She spat in my face and said she would ruin my business. She said she would tell everyone that my bread was made of mice and blackbeetles. Judge Bacon gave judgment for plaintiff, and added that the cake must be returned to defendant. It was his property now. Plaintiff: He's welcome to it, I'm sure He had better stick it in his shop window. It will let people see what a good baker he is. It would make a fine foundation stone for a synagogue. |

| What religion? (1895) A young gentleman who had quarrelled with his fiancee asked to have his presents returned. The lady agreed, but it seems could not find it in her heart to send them all. She was accordingly sued in the County Court. Among the articles claimed were two crucifixes. At the mention of the word crucifix the Judge's attention was aroused: Judge Bacon: Crucifixes? What religion are you? Plaintiff: High Church. Judge Bacon: That's no religion. Jew or Christian? Plaintiff: Christian, of course. Judge Bacon: Protestant or Catholic? Plaintiff: Protestant. Under ordinary circumstances the young gentleman would probably have repudiated the term Protestant; but, High Church as he was, in the presence of the robust commonsense of Judge Bacon, he lapsed into the admission that he was not a Catholic at all. |

| A game of faro (B 1897) Kosminski, a tailor, sued Henry Bill for 5s. for cleaning a coat, and Bill counter-claimed £1 for money spent. Mr. Bamford: We admit the 5s., but say that the £1 is a gambling debt. Defendant: We did play cards, but it was not that. Judge Bacon: Merely a friendly game? Defendant: Oh, yes. Judge Bacon: What game was it? Defendant: A little game of faro. Judge Bacon: Oh, one of the games specially mentioned in the Gambling Act. Who won? Plaintiff: He did; he won all my money from me. The Judge: What happened then? Defendant: I lent him a sovereign. Plaintiff: And you won that. I was skinned clean out. You never saw such cards. Defendant: It was a fair game. Plaintiff: It was fair for you. You got all the people's money. Defendant: It was in your house, with your cards. Plaintiff: Yes; I wish I had never bought them. Judge Bacon: It was a gambling transaction. You cannot recover the £1 you lent. Plaintiff: Can I have my costs? Judge Bacon: They follow the event. But you should pay your debts of honour. |

An Irish mangle (W 1898) An Irish mangle (W 1898)Mrs Donovan was defending an action brought against her for the price of a wringing machine. Defendant: And is it the dirty money they want? I don't want the wringer at all at all, let them take it back and not be after troubling a poor woman. Judge Bacon: But that is not business. Defendant: Business, bedad. Well, sorr, I think it will be moighty fine business for them. How much do they say I owe? Plaintiff: £2 5s 6d. Defendant: It is one pound more than it is worth. What did he not come for the money for? I would not be owing so much now if he called every Saturday as he said. Plaintiff: We called many times; you were always out. Defendant: What are yez after with your interfering ways? Cannot ye let a poor ould woman spake to the gentleman? Plaintiff: She was never at home. Defendant: None of yer impudence, young man. I've not insulted you, and don't you me. Plaintiff: We object to take it back. Defendant: Object away, darlin'. The Usher: Be quiet. Defendant: Isn't that quiet I am? Plaintiff: The wringer would be worn by now. Defendant: Young man, did you ever have an ould mother? It is not worn. I have not been well enough to work. It is true my ould man might have helped me. He is out of work and should help me, but he won't do it. He's like the rest of them, and its little good they are, always saving your riverence. Judge Bacon: Was this a sale or a hiring agreement? Defendant: A hire. Plaintiff: It was sold outright. Judge Bacon: You are trying to deceive the Court. Here is the agreement, it is for the hire. Plaintiff: I did not know that. Judge Bacon: You must have known. Defendant: Shure, your Honour, he did. Those Jew fellows— Plaintiff: We are not Jews, we are Chrisrians. Defendant: Then, it is sorry I am for yer. I'll give up the machine. Judge Bacon: Then you will have to pay 14s 6d for arrears of hire and 3s costs. Defendant: Holy saints. Is it all that money? Then if ye please I'll keep the wringer. Judge Bacon: Then you will have to pay £2 5s 6d, and 13s costs. Defendant: Bad cees to the machine. Whatever's to be done? I'd better put up with the first loss, hadn't I, Laurence (turning to her son), and give it back? Laurence: Yes, mother. Defendant: And yet — it is a good machine, and I've paid some, and shall have to pay more. I'll keep it. Shall I, Laurence? Laurence: Yes, mother. Defendant: I'll keep it if your Honour lets me pay 3s a month. Judge Bacon: We will arrange that when you've made up your mind. Defendant: It's a lot of trouble I have with one son wrong in his head, and my ould man doing nothing. I will give it up. Shall I, Laurence? Laurence: Yes, mother. Defendant: Arrah, but the money I have paid all for nothing. What shall I do? If your Honour was a poor ould woman loike myself with a husband ill and a son an omadhaun, what would you do yourself? Judge Bacon: I think you hanker after the machine. Defendant: I like work. Judge Bacon: You like the wringer? Defendant: Still it is a lot of money to pay. It's a jolly shame. Judge Bacon: That's an inappropriate adjective to put before shame. Defendant: I cannot afford more than 2s a month. Judge Bacon: You said 3s just now. Defendant: Indeed, was it 3s I was after sayin'? Your Honour has a good memory, anyone can see. Judge Bacon: Three shillings a month. Now this is a debt for the machine — not for the hire. Defendant: It is my very own? Judge Bacon: It is your very own. You can pawn it to-morrow if you like. Defendant: It is not that I would be doin'. Come along, Laurence. You should have helped me instead of standin' sayin' nothin'. You're like the men — no use when we want ye. |

| 'Indecent litigation' (W 1902) Alice Doyle sued William Steel to recover £12 19s 6d. They had been engaged for two years and he had given her various presents, including a brooch, bracelets, rings, and a sewing machine. They had quarrelled, and William took back his presents and left the house where Alice was lodging. She admitted there had been previous disagreements, and he had taken back his presents before. The first quarrel was because she danced, and the second about another young man. She admitted she had written to him as follows:

Judge Bacon: These people might have made it up again, and kissed each other one more. I cannot help calling it an indecent litigation. |

| Married 'partly for love' (W 1905) Mr C.M. Mumford, of Ensign street, Shadwell, sought to recover a sum of money which he had paid on a distraint upon his goods made by the bailiffs of the court in consequence of a judgment obtained against Mrs Mumford by a Mr Fred Lovegrove, a licensed victualler, of Gravesend. When the case was called, Mr. Lovegrove, the judgment creditor, did not appear, and Mumford told the judge he had searched everywhere for him in vain. He went on to explain that the debt for which Lovegrove had obtained judgement had nothing to do with him. Mrs Mumford had only been Mrs Mumford for three years; she had been before the widow of a Mr Dunbar. He married her when she had nothing, and he knew nothing of the debt. Judge Bacon: You married her when she had nothing—what for—for love? Plaintiff (a stout, jovial-looking old lighterman): Well, yes, I suppose it was love, partly. Judge Bacon: Partly? How much was love? Plaintiff (deferentially): That I must leave to your Honour exactly to determine—when I tell you that when I married her she had only a little bit of a shop in Brook street, Ratcliff. The little bed I had, and was offered sixpence for it. The house was merely a rabbit hutch. (Mrs Mumford. who was standing behind her husband, at this point, entered an indignant protest of Oh, dear!) Judge Bacon: Yes, but the woman who lived in the rabbit hutch had chairs and tables— Plaintiff: There was a table, your Honour, but the legs were broken off. Judge Bacon (reading the list of goods claimed): And kitchen utensils, fire-irons —how many antimacassars? Were you a widower at the time? Plaintiff: I was, your Honour. I had a furnished house in High street, Shadwell. I have always worked hard for my home, and 1 appreciate my home. Judge Bacon (continuing to read): 'bric-a-brac' —do you mean feathers and flowers under glass, or shells? Plaintiff: I told your Honour I have always appreciated my home. Judge Bacon: Are you sure it was not Mrs Dunbar's home you appreciated? Plaintiff: I assure your Honour she had nothing for me to take. Judge Bacon: As the execution creditor does not attend, I must admit your claim. Plaintiff: And the money I paid, which is in court— Judge Bacon explained that he would get what remained back after the costs of the execution, etc.. had been satisfied. |

| 'The rubbish called roller skating' (B 1910) Mr Johnson, a master tailor, sued Hampstead Roller Skating Palace, alleging a defective board caused him to fall and fracture his ankle. Judge Bacon: Was it real skating, or the rubbish called roller skating? Plaintiff: Roller skating. Planitiff's lawyer: I believe you are a skilled skater? Plaintiff: Yes, for thirty years. Judge Bacon: Is roller skating so old as that? Defendant's lawyer: Yes, sir, quite that. [Roller skating was newly popular in 1910, when Hampstead Roller Skating Pavilion ended its first season at the council's Finchley Road baths, and Hampstead Palace Roller Skating Club, with a rink in a former tram depot in Cressy Road, held its first annual dinner. The rival establishments continued to advertise.] The evidence was contested in two respects. Johnson claimed that when a change of performance was notified he left the maple skating boards and his foot caught in the indentation of an adjoining board, but the defence claimed he was still skating when he fell. He fractured his ankle in two places and spent a month in hospital, and his doctor said it would be three months before his foot was right; but the defence doctor said it would only be a month. Plaintiff's counsel: I suppose that, like lawyers, doctors differ. Judge Bacon: No, no, no, they differ from the side they are called on. The jury awarded the plaintiff £50 damages. |

| Paying bills on Sunday (B 1910) A plaintiff claimed that he regarded money received on Christmas day as a 'Christmas box' rather than as payment of fees due, since it was as impossible to pay a bill on Christmas Day as on a Sunday. Judge Bacon disagreed: The only thing that can prevent you paying a bill on Sunday is not having the money. There is a certain idea that you cannot do so, probably due to the fact that there is a statute by which you are unable to pursue your trade on Sunday. [compare this exchange with Judge Cluer] |

|

In the course of a judgment summons against a Middlesex

street costermonger, the plaintiff gave evidence as a proof of

defendant's means that the latter used a working men's club on Sunday

afternoons. Defendant: Well, I does; what of that? Plaintiff: Why do you go there? Defendant: Same as you, I suppose. A club's a jolly convenient place to get a pint or two of ale when the pubs are shut. The defendant was ordered to pay 2s. monthly. |

Private life, and last days

In 1893 Francis had written, from Kentwell Hall, Long Melford, Suffolk, in response to a request for information about

snuffboxes for The Windsor Magazine, I

have no snuffboxes. I suppose somebody suggested our name but I have

never been a collector and my father, who took snuff, always used the

commonest of boxes.

However, Francis did collect etchings, engravings and paintings. In

1911 Christie, Manson & Woods published a catalogue of Modern

Etchings and Engravings Comprising Etchings by J. M. Whistler, C.

Méryon, and Proofs by S. Cousins ... the property of His Honour Judge

Bacon ... and Engravings of the Early English School and right

is an oil painting 'Fisherfolk on the Beach, Normandy' by Paul Paul

(1865-1937 - born 'Politachi' in Constantinople of Greek parentage)

which he owned and was sold in 2012 for £700.

In 1893 Francis had written, from Kentwell Hall, Long Melford, Suffolk, in response to a request for information about

snuffboxes for The Windsor Magazine, I

have no snuffboxes. I suppose somebody suggested our name but I have

never been a collector and my father, who took snuff, always used the

commonest of boxes.

However, Francis did collect etchings, engravings and paintings. In

1911 Christie, Manson & Woods published a catalogue of Modern

Etchings and Engravings Comprising Etchings by J. M. Whistler, C.

Méryon, and Proofs by S. Cousins ... the property of His Honour Judge

Bacon ... and Engravings of the Early English School and right

is an oil painting 'Fisherfolk on the Beach, Normandy' by Paul Paul

(1865-1937 - born 'Politachi' in Constantinople of Greek parentage)

which he owned and was sold in 2012 for £700.

He featured from time to time in two 'society' diaries:

| 1888, Saturday

28 April: Mr Herkomer's Private View of Water Colours at 148 Bond St.

Promised to fetch Tabs at 4 o'c. Busy altering dress all morg. Lin in

all day photoing & doing Academy cut. Went in brougham with Ju

& Tabbie to Herkomers. Saw him, sister in law & little girl,

Messels, Lethbridge etc. Mr Huish lent me his ticket for Grosvenor

Gallery Private View. Ju went home & Tabbie & self went to Private View. Saw Judge Bacon, Lady Mackenzie, Blackburns, Lady Elcho etc. Very tired, went & had cups of tea at Tabs after, brought Maud's hat home. Letter fr. Mother about Charlie's engagement. 1892, Friday 27 May: Mrs. Medley 4.30. Lovely day, v. hot. Lin rode early. Girls late. I took cab to Mrs. F.C.B’s asked Connie to go to dine at Mr Stone’s Members Mansions & to opera after. Sir T. Lucas’ box for tonight Manon [Jules Massenet's most famous work, of 1884] & Van Dyke as Count des Grieux. Delighted with his voice most exquisite & plays so well too. Connie B. & self dined at Members Mansions Mr Stone’s rooms. Lin joined us when half thro’ dinner. Drove in two hansoms to opera which we all enjoyed immensely, music charming so bright & full of melody. Judge Bacon came & sat thro’ one entire act in our box. Mr Stone wanted to take us on to supper at Criterion after but afraid of Mrs. B. being anxious about Connie. Lin & Mr S. off together. 1896, Thursday 20 February: Mr Booth’s invitation to Theatricals at Albert Hall. Going tomorrow instead. Maud & I called on Miss Thornton, Lady M. Maud lunched at Cohens, fetched her & called on Nembhards & Mrs. Rider Haggard. Tilda came to stay. Judge Bacon called. 1897, Saturday 10 April: Lady Lawrence's dinner 8 o'c, ac'pt for Lin, Maud & self. Drove with Maud to Miss Ratcliffe, Marshall & Snelgrove. V. charming dinner at Lady Ls, 22. Table v. lovely with orchids. Sir & Lady Barnes, Lord Hobhouse, Judge Bacon, Mr. & Mrs. Rutherford of Westminster, 2 Lawrence boys, dau, Miss Chamberlain, Mr. Sterne a little deaf. M. long letter fr. Lennie. 1900, Saturday 10 November: Maggie Henderson’s marriage. Out morg. did flowers, v. tired. To M.H’s wedding with Lin, church lined with Life Guards. Sat with Lady Hardman, Judge Bacon, Maud who met us there. On to house, v. crowded. Many pretty women. Parish, Lola, Snagg, Mayne, etc, etc. Maud looked sweetly pretty. Roy dined at Mrs. Messel’s with Lennie & M, Cap. Meicklejohn, Hylda. To San Toy [a Chinese musical comedy of 1899] after. Lin & self to Alexanders, huge box. A Debt of Honour [a one-act play of that year by Sydney Grundy, who adapted and 'cleaned up' foreign plays for the British stage, and collaborated with Sir Arthur Sullivan] v. improper. Judge Bacon with us. 1901, Tuesday 23 Only Lady Lockwood called. Col & Mrs. Welby & Miss Innes dined here. Went to stores morg. Most tiring spent 15/10 on fringe, flowers, fish etc, £1 wine. V. pleasant evg. tho’ disappointed in Weld Blundell [member of a prominent Roman Catholic family] & Judge Bacon. 1901, Thursday 25 July Awful storm lasted nearly all day. Lin much detained with work. Model here to lunch. Went in brougham to Whiteley for fish & fowl. Left letter Judge Bacon. Left Jamaica div. £1.13.6 at Bank. Maud here on my return, remains night |

Francis Bacon's commitment to the house at Compton Beauchamp and its local community remained strong; shortly before his death he had been making arrangements to hold Coronation festivities there. The Berks, Bucks & Oxon Archæological Journal

(vols 16-17) reports a visit in 1910, where they saw moulded beams

discovered during a restoration he had undertaken. They noted

that the lawns and

gardens which rise up the hill sife in terraces are shut in with

splendid elms, and there is a dark yew-alley called the cloister walk. (Their excursion, by special train, ran behind schedule and was curtailed by a downpour.)

Following his death, Judge Alan Macpherson

(b.1857) was appointed on a temporary basis. A Scot from Blairgowrie,

Perthshire, he was educated at Winchester and

Exeter College, Oxford, graduating, and called to the Bar at Lincoln's

Inn, in 1881; he worked on the south east circuit, and married in 1889.

Appointed a county court judge in 1912, he transferred to the south

west in 1920, holding courts at Cheltenham, Chipping Norton,

Cirencester, Dursley, Gloucester, Malmesbury, Newent, Newnham,

Northleach, Stow on-the-Wold, Stroud, Tewkesbury, Thornbury, and

Winchcombe, with jurisdiction in Admiralty at Gloucester, and in

Bankruptcy at Cheltenham, and Gloucester. His home was The Hall,

Bakewell in Derbyshire. He retired in 1929, and died six months later. Sir William Macpherson (b.1926), who as a retired High Court judge led the Stephen Lawrence enquiry, is a member of this family and clan.

The

long-term successor to Judge Bacon, but at Whitechapel and Shoreditch

(rather than Bloomsbury), was the equally often-quoted Judge Albert Cluer.

»»» Judge Albert Cluer | ««« Policing, Magistrates' & Other Courts | ««« History