The Tower

Liberties

See here for the history of the areas

that became part of the

Liberties of the Tower of London.

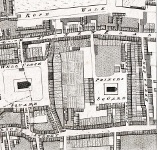

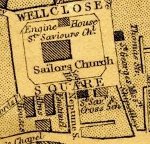

By Letters Patent of 1686, King James II

included the areas of Minories, the Old Artillery Ground and

Wellclose among the Tower

Liberties, although the Tower held

no

land in the area. Right [b+w

version is in higher resolution] is

Stow / Strype's map of c1720 showing the areas involved (Wellclose

Square, formerly known

as Marine Square, is in the top right), and part of the 1878 Vestry

map. The western edge of the

Precinct of Wellclose was

Well Street [now Ensign Street], its southern edge Neptune Street [now

Wellclose Street], and

to the north was Graces Alley, later home to Wilton's Music Hall. See also Rosemary Lane

[now Royal Mint Street].

See here for the history of the areas

that became part of the

Liberties of the Tower of London.

By Letters Patent of 1686, King James II

included the areas of Minories, the Old Artillery Ground and

Wellclose among the Tower

Liberties, although the Tower held

no

land in the area. Right [b+w

version is in higher resolution] is

Stow / Strype's map of c1720 showing the areas involved (Wellclose

Square, formerly known

as Marine Square, is in the top right), and part of the 1878 Vestry

map. The western edge of the

Precinct of Wellclose was

Well Street [now Ensign Street], its southern edge Neptune Street [now

Wellclose Street], and

to the north was Graces Alley, later home to Wilton's Music Hall. See also Rosemary Lane

[now Royal Mint Street].

What

were the implications of this 'Liberty'? It meant

that authority

for the maintenance of law and order within the area lay with the

Governor of the Tower, sitting with appointed magistrates. They dealt

with all criminal charges, great and small, and those accused

were committed to Newgate for safe custody. In civil matters,

it

served as a Court of Record and Request for

the recovery of small debts (like

a modern-day

County Court), and had its own 'gaol of the Tower Royalty'. An example

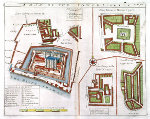

of this alternative jurisdiction is from 1798, when at the Middlesex

sessions in July a group of men (including Lancelot Henry,

later a

churchwarden at St George-in-the-East) stood accused of crimes (which

they denied), and were bailed, but claimed that as the alleged events

occurred within the Liberty the quarter sessions had no authority to

hear the case. (Click here for documents and transcript:

we don't know the nature of the charges or the final

verdict.)

What

were the implications of this 'Liberty'? It meant

that authority

for the maintenance of law and order within the area lay with the

Governor of the Tower, sitting with appointed magistrates. They dealt

with all criminal charges, great and small, and those accused

were committed to Newgate for safe custody. In civil matters,

it

served as a Court of Record and Request for

the recovery of small debts (like

a modern-day

County Court), and had its own 'gaol of the Tower Royalty'. An example

of this alternative jurisdiction is from 1798, when at the Middlesex

sessions in July a group of men (including Lancelot Henry,

later a

churchwarden at St George-in-the-East) stood accused of crimes (which

they denied), and were bailed, but claimed that as the alleged events

occurred within the Liberty the quarter sessions had no authority to

hear the case. (Click here for documents and transcript:

we don't know the nature of the charges or the final

verdict.)

The Court House, on the south side of

Wellclose Square at the corner with Neptune Street was erected some

time after 1687, and there are good records and pictures of the

building before demolition, including Barbon's staircase to the first

floor. (In its latter years it was used as

a German club, and then became a

paint works - the courtroom became a storeroom, and the staircase was

painted in shiny cocoa brown.) The prison behind, on

the

corner of Neptune [later Wellclose] Street, was

commonly known as the 'Sly House', because it was said that felons who

entered

it left by a subterranean passage to the Tower and the docks, from

which the convict ship Success

left. The

reality may have been more prosaic: it was used mainly for debtors who

were tried at the local court. Right

is the Watch House in

the Square, c1925, used in earlier times by the nightwatchmen.

The Court House, on the south side of

Wellclose Square at the corner with Neptune Street was erected some

time after 1687, and there are good records and pictures of the

building before demolition, including Barbon's staircase to the first

floor. (In its latter years it was used as

a German club, and then became a

paint works - the courtroom became a storeroom, and the staircase was

painted in shiny cocoa brown.) The prison behind, on

the

corner of Neptune [later Wellclose] Street, was

commonly known as the 'Sly House', because it was said that felons who

entered

it left by a subterranean passage to the Tower and the docks, from

which the convict ship Success

left. The

reality may have been more prosaic: it was used mainly for debtors who

were tried at the local court. Right

is the Watch House in

the Square, c1925, used in earlier times by the nightwatchmen.

The landlord of the

adjacent King's Arms (33

Wellclose Square, linked to what later became 211 St George Street) was

responsible for feeding the prisoners: a doorway beside its main

entrance led up a stone staircase to the first floor of the Court

House, and down to a courtyard and the prison. When the prison closed and the King's

Arms took

over the site, the landlord would open the cells, with their

heavily-bolted doors, grilles, plank beds, fetters and straitjackets,

to visitors. Some of these fixtures have now been preserved at the

Museum of

London, including inscriptions scratched with pine cones on the

wooden panels [right]. Among

them is one to Stockley, who invented the 'pitch

plaster'

which was clapped on victims' mouths to keep them silent; the

optimistic verse The

cupboard is empty, to our sorrow; let's hope it will be full to-morrow; and the pathetic

plea Please

to remember the poor debtors, 1758. As many

advertisements in the Times

show, in the 18th and early 19th centuries estate agents regularly left

prospectuses for East London properties (often sold by auction at Garraway's Coffee House

in the City) at the King's Arms.

The freehold was sold in the 1880s, with Thomas Wasmuth as sitting

tenant and licensee (at least one of his children was baptized at St

George-in-the-East). It was demolished around 1912.

The landlord of the

adjacent King's Arms (33

Wellclose Square, linked to what later became 211 St George Street) was

responsible for feeding the prisoners: a doorway beside its main

entrance led up a stone staircase to the first floor of the Court

House, and down to a courtyard and the prison. When the prison closed and the King's

Arms took

over the site, the landlord would open the cells, with their

heavily-bolted doors, grilles, plank beds, fetters and straitjackets,

to visitors. Some of these fixtures have now been preserved at the

Museum of

London, including inscriptions scratched with pine cones on the

wooden panels [right]. Among

them is one to Stockley, who invented the 'pitch

plaster'

which was clapped on victims' mouths to keep them silent; the

optimistic verse The

cupboard is empty, to our sorrow; let's hope it will be full to-morrow; and the pathetic

plea Please

to remember the poor debtors, 1758. As many

advertisements in the Times

show, in the 18th and early 19th centuries estate agents regularly left

prospectuses for East London properties (often sold by auction at Garraway's Coffee House

in the City) at the King's Arms.

The freehold was sold in the 1880s, with Thomas Wasmuth as sitting

tenant and licensee (at least one of his children was baptized at St

George-in-the-East). It was demolished around 1912.

The

Precinct's distinctive legal status gradually came to an end as new

local government legislation took

effect: from 1855 (or earlier) the area fell under the jurisdiction of

the local Magistrates' Court. But

the traditional

triennial Beating

of the

Bounds,

on Ascension Day, continued until

1897 for the Liberty of Wellclose. The Lieutenant of the

Tower came,

accompanied by an escort of Tower warders, followed by officials and

schoolboys wearing ribbons

red, white and blue on their bosoms, and carrying willow

wands. These boys were the sons of soldiers quartered at the

Tower. Many

parish churches, including St George's, also used

to beat the

bounds,

perambulating the borders with hymns and prayers - as this 1882

programme [left]

shows:

the event was also a farewell to Harry Jones as Rector. Right is a 1910 picture

from the

Tower's own ceremony from 1910. The

tradition continues in some places, though with no legal significance; it was revived for a few years by Fr Aquinas at St Paul Dock Street in the 1970s.

The

Precinct's distinctive legal status gradually came to an end as new

local government legislation took

effect: from 1855 (or earlier) the area fell under the jurisdiction of

the local Magistrates' Court. But

the traditional

triennial Beating

of the

Bounds,

on Ascension Day, continued until

1897 for the Liberty of Wellclose. The Lieutenant of the

Tower came,

accompanied by an escort of Tower warders, followed by officials and

schoolboys wearing ribbons

red, white and blue on their bosoms, and carrying willow

wands. These boys were the sons of soldiers quartered at the

Tower. Many

parish churches, including St George's, also used

to beat the

bounds,

perambulating the borders with hymns and prayers - as this 1882

programme [left]

shows:

the event was also a farewell to Harry Jones as Rector. Right is a 1910 picture

from the

Tower's own ceremony from 1910. The

tradition continues in some places, though with no legal significance; it was revived for a few years by Fr Aquinas at St Paul Dock Street in the 1970s.

The

Royalty

Theatre [left] in

Well Street was

built by subscription in 1786 and run by John 'Plausible' Palmer - a

man of the most versatile and

eminent talents, but destitute of prudence - but was not

licensed. After the opening

performances of As You Like It and

the farce Miss in her Teens, the

profits given to the new London Hospital, it closed until a licence for

the hybrid musical entertainments permitted by law - interludes, pantomimes

and other species of the irregular drama - was granted.

Later

it fell into the hands of various

adventurers (Nightingale, London and

Middlesex 1815).

At some point a gasworks (with a 'gasometer') was built north of the

theatre, next to the stage, to provide lighting both for the theatre

(Palmer's brother Robert had taken part in a display of an 'Aeropyric

Branch' at the Lyceum in 1789 which was probably a demonstration of gas

lighting) and for the neighbourhood, a prosperous manufacturing district, at

an annual profit of £1,000. The Chartered Gas, Light & Coke Co.

bought this 'East London Gas Works' plus the theatre at auction in

1820. In April 1826 the scenery above the stage caught fire during a

performance of Kendrick the Accursed,

for which half a pound of powder was used to simulate the eruption of

Mount Etna; apparently the gas lights beside the stage had not been

turned off.

The

Royalty

Theatre [left] in

Well Street was

built by subscription in 1786 and run by John 'Plausible' Palmer - a

man of the most versatile and

eminent talents, but destitute of prudence - but was not

licensed. After the opening

performances of As You Like It and

the farce Miss in her Teens, the

profits given to the new London Hospital, it closed until a licence for

the hybrid musical entertainments permitted by law - interludes, pantomimes

and other species of the irregular drama - was granted.

Later

it fell into the hands of various

adventurers (Nightingale, London and

Middlesex 1815).

At some point a gasworks (with a 'gasometer') was built north of the

theatre, next to the stage, to provide lighting both for the theatre

(Palmer's brother Robert had taken part in a display of an 'Aeropyric

Branch' at the Lyceum in 1789 which was probably a demonstration of gas

lighting) and for the neighbourhood, a prosperous manufacturing district, at

an annual profit of £1,000. The Chartered Gas, Light & Coke Co.

bought this 'East London Gas Works' plus the theatre at auction in

1820. In April 1826 the scenery above the stage caught fire during a

performance of Kendrick the Accursed,

for which half a pound of powder was used to simulate the eruption of

Mount Etna; apparently the gas lights beside the stage had not been

turned off.

The

firemen could only stand at either

end of the theatre and throw the water on the flames

as well as they could; there was more concern about the two

adjacent sugar refineries. All that survived was the grand piano snatched from the green room by an unknown

sailor. A

replacement building, the Royal Brunswick [right], was erected in seven months, with

a heavy iron

roof. A few days after it opened on 28 February 1828, during a

rehearsal of Guy Mannering, the

roof fell

in, crushing to death Mr Maurice, one of the proprietors, and twelve

others. See here

for the story of the acquisition of the site for the Sailors' Home.

The

firemen could only stand at either

end of the theatre and throw the water on the flames

as well as they could; there was more concern about the two

adjacent sugar refineries. All that survived was the grand piano snatched from the green room by an unknown

sailor. A

replacement building, the Royal Brunswick [right], was erected in seven months, with

a heavy iron

roof. A few days after it opened on 28 February 1828, during a

rehearsal of Guy Mannering, the

roof fell

in, crushing to death Mr Maurice, one of the proprietors, and twelve

others. See here

for the story of the acquisition of the site for the Sailors' Home.

In a district where

most building projects were piecemeal and chaotic, Wellclose Square

(originally known as Marine Square) and the smaller Prince's

Square to the east were the

only planned developments of their time, and even here (as noted below)

the houses were of various periods, and were constantly being modified,

extended and rebuilt. Nicholas Barbon

(c1640-98) was its principal developer. His full name was Nicholas

If-Jesus-Christ-Had-Not-Died-For-Thee-Thou-Hadst-Been-Damned Barbon,

given by his Puritan father Praisegod

Barbon (Barebone), leather-seller,

MP, fanatical anti-monarchist and general nuisance. Returning

from Holland in the 1670s, Nicholas was a major speculator in the West

End, leasing plots from the Crown

in the aftermath of the Great Fire of London, seeing an opportunity to

provide houses for well-to-do

merchants. He also acquired three sites in East London, paying £3,200

for the freehold of Wellclose Square (though he was slow in making

payment). In 1682-3 he cleared the site and laid out a square with

diagonal passageways at each corner, to insulate it from the noise and

dirt of the surrounding area and maximise the frontages. (Of these

passageways, only Grace's Alley on the NW corner remains, plus the now

un-named cut-through on the SW, variously known in the 19th century as

Harrrod's, Harad's, Harrald's and Hard's Court or Place; Ship Alley on

the SE corner and North East Passage have disappeared. Shorter [now

Fletcher] and Neptune [now Wellclose] Streets connected the square

respectively to Cable Street

and The Highway.)

In a district where

most building projects were piecemeal and chaotic, Wellclose Square

(originally known as Marine Square) and the smaller Prince's

Square to the east were the

only planned developments of their time, and even here (as noted below)

the houses were of various periods, and were constantly being modified,

extended and rebuilt. Nicholas Barbon

(c1640-98) was its principal developer. His full name was Nicholas

If-Jesus-Christ-Had-Not-Died-For-Thee-Thou-Hadst-Been-Damned Barbon,

given by his Puritan father Praisegod

Barbon (Barebone), leather-seller,

MP, fanatical anti-monarchist and general nuisance. Returning

from Holland in the 1670s, Nicholas was a major speculator in the West

End, leasing plots from the Crown

in the aftermath of the Great Fire of London, seeing an opportunity to

provide houses for well-to-do

merchants. He also acquired three sites in East London, paying £3,200

for the freehold of Wellclose Square (though he was slow in making

payment). In 1682-3 he cleared the site and laid out a square with

diagonal passageways at each corner, to insulate it from the noise and

dirt of the surrounding area and maximise the frontages. (Of these

passageways, only Grace's Alley on the NW corner remains, plus the now

un-named cut-through on the SW, variously known in the 19th century as

Harrrod's, Harad's, Harrald's and Hard's Court or Place; Ship Alley on

the SE corner and North East Passage have disappeared. Shorter [now

Fletcher] and Neptune [now Wellclose] Streets connected the square

respectively to Cable Street

and The Highway.)

On

the south side Barbon built

two-storey houses with attics, with good-sized rooms and staircases

with twisted balusters. In 1680 Barbon opened a fire insurance office

at the Royal Exchange, and in 1683 one of the first schemes was set up

in the Square, with a permanent engine housed on the north side. His

convoluted commercial practices - assigning or mortgaging leases to

others - are described in detail by Elizabeth McKellar inThe Birth of Modern London:

the Development & Design of the City 1660-1720 (1999).

Barbon's contemporary Roger

North, a lawyer and biographer, commented his

house in the morning [is] like a court, crowded with suitors for money.

And he kept state, coming down at his own time like a magnifico, in

deshabille, and so to

discourse with them. And having very much work,

they were loath to break finally, and upon a new job taken they would

follow and worship him like an idol, for then there was fresh money.

The

houses on the

north side were later and larger. At no.26

was a house with

Venetian windows, with a five-bay boarded house behind. Despite the

Fire, houses were built or rebuilt in timber, and Roger Guillery in The Small House in Eighteenth

Century London: A Social and Architectural History (2004)

comments these were not modest

houses, and they incorporated fashionable classical embellishments,

like the ground floor Serliana.

A

number of the

houses were originally occupied by Scandinavian timber merchants. In

the chapter

on Wellclose Square in their informative book Wapping 1600-1800: A Social

History of an Early Modern London Maritime Suburb

(East London Historical Society 2009) Derek Morris and

Ken Cozens list

a number of local families, identified from insurance policies, court

records and wills, including

A

number of the

houses were originally occupied by Scandinavian timber merchants. In

the chapter

on Wellclose Square in their informative book Wapping 1600-1800: A Social

History of an Early Modern London Maritime Suburb

(East London Historical Society 2009) Derek Morris and

Ken Cozens list

a number of local families, identified from insurance policies, court

records and wills, including| References to Wolff

in John Wesley's Journal: 1783: 28.02, 04.06,

17.12; 1784: 18.02; 1785: 04.08 (Balham); 1786: 04.01; 1787: 03.01,12.12

(Ballam) (Testament); 1788: 14.01 (Bal[h]am.

sermon), 18.01 (Mrs Wolff), 21.02, (Bal[h]am (sermon), 13.11; 1789: 20.01 (letters),

01.12 (Bal[h]am); 1790: 20.01, 16.02

(Tuesday: I

retired to Balham for a few days, in order to finish my sermons and put

all my things in order), 18.02 (Thursday: 3

with Mrs Wolff, Wandswor[th], 8 Balham, supper), 02.10, 06.11(at Mr. Wolff's, christened), 29.12;

1791: 31.01. |

The

next generation departed somewhat from Lutheran / Methodist piety, and

were less fortunate in business. Georg's son Jens, who inherited the consulate

from his father, has been described as a'virtually unrewarded' hero of

the Danes - see Den

Danske Kirke i London 1692-1992

- and was the last person to be interred in the vault below the Danish

church, in 1845, then in the hands of Bo'sun Smith with whom he had

been in conflict. His wife

Isabella had a long-standing

affair with Sir

Thomas Lawrence,

from some time after he began his portrait of her in 1803 until her

divorce in 1813; two years later his picture [left], depicting her as the

Ethyrean Sibyl from the Sistine chapel, apparently examining a book of

Michaelangelo's engravings, was exhibited at the Royal Academy, and is

now at the Art Institute of Chicago. (Some observers note that she

appears to have no clavicle.) Georg's daughter Elizabeth married John Dorville,

but had an equally nororious liasion with the noted naturalist George

Montague, producing two children, who took her husband's surname -

Henry and Elizabeth Dorville.

The

next generation departed somewhat from Lutheran / Methodist piety, and

were less fortunate in business. Georg's son Jens, who inherited the consulate

from his father, has been described as a'virtually unrewarded' hero of

the Danes - see Den

Danske Kirke i London 1692-1992

- and was the last person to be interred in the vault below the Danish

church, in 1845, then in the hands of Bo'sun Smith with whom he had

been in conflict. His wife

Isabella had a long-standing

affair with Sir

Thomas Lawrence,

from some time after he began his portrait of her in 1803 until her

divorce in 1813; two years later his picture [left], depicting her as the

Ethyrean Sibyl from the Sistine chapel, apparently examining a book of

Michaelangelo's engravings, was exhibited at the Royal Academy, and is

now at the Art Institute of Chicago. (Some observers note that she

appears to have no clavicle.) Georg's daughter Elizabeth married John Dorville,

but had an equally nororious liasion with the noted naturalist George

Montague, producing two children, who took her husband's surname -

Henry and Elizabeth Dorville.

Left are

detailed maps of the area by John Rocque (1742) and Horwood

(1792). In

1815

Nightingale

described it as a

pretty little neat square. But it was not all

housing: a sugar

refinery

was built in the square by 1794

(and by 1854 there were five). There premises, at no.48, were used

until 1851 in turn by Pritzler, Engell, Martineau, and Henrickson. It

was still listed as a sugarhouse in the 1861 and 1871 censuses, but was

taken over, together with no.49,

as a pickle factory by George Whybrow

and Sons, variously described as export

oilmen, oil merchants

and Italian warehousemen.

The firm began trading around 1825 and had other premises at 4 Minories

and 10 Royal Mint Street. In the 1830s Eliza Whybrow insured 1

Cannon Street Road as an oil

warehouse keeper. One of their sites had a steam-powered lift

between the floors. They manufactured pickles, sauces, bottled fruits

and other goods, imported capers, salad oil and castor oil and exported

to the colonies, especially Australia - detailed in this advertisement from the Australian Handbook of

1877, which pictures the Wellclose Square works and quotes from a

testimonial in The Grocer

of 22 May 1875:

Left are

detailed maps of the area by John Rocque (1742) and Horwood

(1792). In

1815

Nightingale

described it as a

pretty little neat square. But it was not all

housing: a sugar

refinery

was built in the square by 1794

(and by 1854 there were five). There premises, at no.48, were used

until 1851 in turn by Pritzler, Engell, Martineau, and Henrickson. It

was still listed as a sugarhouse in the 1861 and 1871 censuses, but was

taken over, together with no.49,

as a pickle factory by George Whybrow

and Sons, variously described as export

oilmen, oil merchants

and Italian warehousemen.

The firm began trading around 1825 and had other premises at 4 Minories

and 10 Royal Mint Street. In the 1830s Eliza Whybrow insured 1

Cannon Street Road as an oil

warehouse keeper. One of their sites had a steam-powered lift

between the floors. They manufactured pickles, sauces, bottled fruits

and other goods, imported capers, salad oil and castor oil and exported

to the colonies, especially Australia - detailed in this advertisement from the Australian Handbook of

1877, which pictures the Wellclose Square works and quotes from a

testimonial in The Grocer

of 22 May 1875: George died in 1873, and the 1881 census shows 48 & 49 Wellclose

Square as uninhabited - they had moved to new premises at 290 Cable

Street, between Bewley and Albert Streets, shown right on Goad's 1899 insurance map

prior to closure. His relatives Francis and Henry took on the

business for a time, but their partnership was dissolved in 1885.

Francis continued to run it; an attempt to re-finance it failed in

1897. It was

wound up in 1899, and an order of the Chancery court was made the

following March for the sale of the lease,

goodwill, stock-in-trade and fixtures of the business of Pickle

Manufacturers for many years carried on by George Whybrow Limited, and

their predecessors at 290 Cable-street Shadwell together with trade marks, plant and

machinery and the option of purchasing current book debts.

George died in 1873, and the 1881 census shows 48 & 49 Wellclose

Square as uninhabited - they had moved to new premises at 290 Cable

Street, between Bewley and Albert Streets, shown right on Goad's 1899 insurance map

prior to closure. His relatives Francis and Henry took on the

business for a time, but their partnership was dissolved in 1885.

Francis continued to run it; an attempt to re-finance it failed in

1897. It was

wound up in 1899, and an order of the Chancery court was made the

following March for the sale of the lease,

goodwill, stock-in-trade and fixtures of the business of Pickle

Manufacturers for many years carried on by George Whybrow Limited, and

their predecessors at 290 Cable-street Shadwell together with trade marks, plant and

machinery and the option of purchasing current book debts.| Or take the case of George Whybrow, Limited, where investors are asked to acquire, at a cost of £60,000, the business of a pickle, sauce, &c, manufacturer. As the business was established in the beginning of the present century, it would obviously be possible to show what the profits have been over a series of years; but instead of any particulars of the kind, we are treated to an estimate of what the company is going to earn in the future, and are asked to reflect upon the profitable natures of such joint-stock companies as Maple and Co., J. & P. Coats, Harrod's Stores, A. and F. Pears, the leading drapery companies, Price's Candle Co., Bryant and May's, and Guinness. Could anything be more absurd? |

As

well as those linked to the Bo'sun Smith's church, the Square

housed other hostels

and other welfare organisations, including the Jewish Joel Emanuel Almshouse (a trust

which continues to the present day, based in north London) - shown on

1868 map right in the

south-west corner - and at no.32 the Hand in Hand Home for Aged and Decayed

Tradesmen,

founded in 1840 and previously based at 5 Duke's Place from 1843, and

22 Jewry Street from 1850 before moving to the Square in 1854, and

again in 1878 to 23 Well Street, Hackney.

This was one of a trio of organisations set up to protect members of

the Jewish community, for whom care and respect for the elderly and

needy is a core priority; the Poor Law

system failed to meet their social, religious and dietary needs. The

other two were the Widow's Home Asylum (founded 1843, and from

1857-1880 at 67 Great Prescott [Prescot] Street - more here)

and the Jewish Workhouse or Home (1871). The three later came together

in Hackney and Stepney Green and merged in 1894, moving to Nightingale

Lane in Wandsworth Common in 1907. (Now known as Nightingale,

in 2001 it was the largest Jewish residential and nursing home in

Europe. Ted 'Kid' Lewis, a local Jewish boxer, whose story is noted here, was a resident

from 1966 until his death in 1970.) See here for a Jewish

orphanage elsewhere in the parish which also became the basis of a

present-day trust elsewhere.

As

well as those linked to the Bo'sun Smith's church, the Square

housed other hostels

and other welfare organisations, including the Jewish Joel Emanuel Almshouse (a trust

which continues to the present day, based in north London) - shown on

1868 map right in the

south-west corner - and at no.32 the Hand in Hand Home for Aged and Decayed

Tradesmen,

founded in 1840 and previously based at 5 Duke's Place from 1843, and

22 Jewry Street from 1850 before moving to the Square in 1854, and

again in 1878 to 23 Well Street, Hackney.

This was one of a trio of organisations set up to protect members of

the Jewish community, for whom care and respect for the elderly and

needy is a core priority; the Poor Law

system failed to meet their social, religious and dietary needs. The

other two were the Widow's Home Asylum (founded 1843, and from

1857-1880 at 67 Great Prescott [Prescot] Street - more here)

and the Jewish Workhouse or Home (1871). The three later came together

in Hackney and Stepney Green and merged in 1894, moving to Nightingale

Lane in Wandsworth Common in 1907. (Now known as Nightingale,

in 2001 it was the largest Jewish residential and nursing home in

Europe. Ted 'Kid' Lewis, a local Jewish boxer, whose story is noted here, was a resident

from 1966 until his death in 1970.) See here for a Jewish

orphanage elsewhere in the parish which also became the basis of a

present-day trust elsewhere.

In

the 19th century no.6 housed

the office of the St George-in-the-East Poor Law Guardians. Two timber-framed

buildings reflecting the 18th century maritime history of the area, and

which remarkably survived later reconstruction, were the cottage at

no.26, at the corner of Stable

Yard (with a Venetian attic window) [pictures

1 & 2; 3 & 4 show front and rear in 1943], and no.27, in the yard behind, a

'colonial-style' house of four storeys and cellar [pictures 5 & 6 (1 Sept 1911) - the sign reads Everett & Co,

though earlier the sugar bakers Ellerman had been based here].

In

the 19th century no.6 housed

the office of the St George-in-the-East Poor Law Guardians. Two timber-framed

buildings reflecting the 18th century maritime history of the area, and

which remarkably survived later reconstruction, were the cottage at

no.26, at the corner of Stable

Yard (with a Venetian attic window) [pictures

1 & 2; 3 & 4 show front and rear in 1943], and no.27, in the yard behind, a

'colonial-style' house of four storeys and cellar [pictures 5 & 6 (1 Sept 1911) - the sign reads Everett & Co,

though earlier the sugar bakers Ellerman had been based here]. Famous

residents

Down

the

years Wellclose Square had a number of notable residents, and became

something of a

haven for free-thinkers, before it fell into decline. Indeed, from

1744-62 it housed a small dissenting academy, in the home of Dr

Samuel Morton Savage (1721-91).

Students boarded with families, and the library and lectures

were in the house. Morton taught classics and mathematics, and Dr David

Jennings, the Principal, taught theology.

Other notable residents included:

Sir Felix Feast, brewer, freeman and

briefly Sheriff of London; here in the early years of the 18th century

he brought up Richard Cooper

(1700-64), orphaned at the age

of nine, who moved to Edinburgh around 1727 and as

an engraver with architectural interests became a significant figure in

the Scottish enlightenment; he had also been associated with the

Swedish artist George

Englehart Schröder (1684-1750), who drew Cooper's portrait [right] before returning to Sweden

in 1725 and may have had connections with the Swedish Church

in Prince's Square (for more details on all this, see Dr Joe Rock's

site here).

Sir Felix died intestate in 1724, provoking a Chancery case (5 April

1726) about the provision made at the time of his marriage for his wife

(she lived until in 1755) and future children.

Sir Felix Feast, brewer, freeman and

briefly Sheriff of London; here in the early years of the 18th century

he brought up Richard Cooper

(1700-64), orphaned at the age

of nine, who moved to Edinburgh around 1727 and as

an engraver with architectural interests became a significant figure in

the Scottish enlightenment; he had also been associated with the

Swedish artist George

Englehart Schröder (1684-1750), who drew Cooper's portrait [right] before returning to Sweden

in 1725 and may have had connections with the Swedish Church

in Prince's Square (for more details on all this, see Dr Joe Rock's

site here).

Sir Felix died intestate in 1724, provoking a Chancery case (5 April

1726) about the provision made at the time of his marriage for his wife

(she lived until in 1755) and future children.

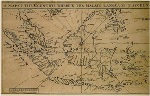

Thomas Bowrey (1662-1713), sea

captain and free merchant,

probably from a Wapping family, who travelled and traded extensively in

the East Indies between 1669-88; he then married his cousin Mary

Gardiner, daughter of a Wapping apothecary, and settled in Wellclose

Square until their deaths (she outlived him by two years). He was a

Younger Brother of Trinity

House, and is particularly remembered for

producing the first English-Malay

dictionary in 1701 [his map of Malay-speaking areas right]. He also published travel

writings, including a Geographical

Account of the Countries round the Bay of Bengal 1669-1679, which

includes this illustration [far

right] and an account of how on the Bay of Biscay he and his

colleagues observed the effect of communal drug-taking (bhang, made from crushed cannabis

pods mixed with milk) and each bought a pint to try for themselves:

Thomas Bowrey (1662-1713), sea

captain and free merchant,

probably from a Wapping family, who travelled and traded extensively in

the East Indies between 1669-88; he then married his cousin Mary

Gardiner, daughter of a Wapping apothecary, and settled in Wellclose

Square until their deaths (she outlived him by two years). He was a

Younger Brother of Trinity

House, and is particularly remembered for

producing the first English-Malay

dictionary in 1701 [his map of Malay-speaking areas right]. He also published travel

writings, including a Geographical

Account of the Countries round the Bay of Bengal 1669-1679, which

includes this illustration [far

right] and an account of how on the Bay of Biscay he and his

colleagues observed the effect of communal drug-taking (bhang, made from crushed cannabis

pods mixed with milk) and each bought a pint to try for themselves:

| It

Soon tooke its Operation Upon most of us, but merrily, Save upon two of

our Number, who I suppose feared it might doe them harme not beinge

accustomed thereto. One of them Sat himselfe downe Upon the floore, and

wept bitterly all the Afternoone, the Other terrified with feare did

runne his head into a great Mortavan Jarre, and continue in that

posture 4 hours or more; 4 or 5 of the number lay upon the Carpets

(that were Spread in the roome) highly Complimentinge each Other in

high termes, each man fancyinge himself noe lesse than an Emperour. One

was quarrelsome and fought with one of the wooden Pillars of the Porch,

until he had left himselfe little Skin upon the knuckles of his

fingers. My Selfe and one more Sat sweating for the Space of 3 hours in

Exceeding Measure ... |

Dr

Hayyim

Samuel Jacob Falk

(c1708-1782) [right] was a

Kabbalistic rabbi and alchemist. Charged with

sorcery in his native Westphalia, he fled to London and settled in

Wellcose Square in 1742 where he lived until his death. The Jews of

London called him the 'Baal Shem of London' because of his alleged

miraculous or magical powers involving the divine Name. He kept a diary

of dreams and the Kabbalistic names of angels, now held in the library

of the United Synagogue in London.

Dr

Hayyim

Samuel Jacob Falk

(c1708-1782) [right] was a

Kabbalistic rabbi and alchemist. Charged with

sorcery in his native Westphalia, he fled to London and settled in

Wellcose Square in 1742 where he lived until his death. The Jews of

London called him the 'Baal Shem of London' because of his alleged

miraculous or magical powers involving the divine Name. He kept a diary

of dreams and the Kabbalistic names of angels, now held in the library

of the United Synagogue in London.

Thomas

Day (1748-89), author, politician and disciple

of

Rousseau, though he lived most of later life at the family estate in

Barehill, Berkshire, was born in Wellclose Square, at a house which

went with his father's

job as 'Collector of the Customs Outward in the Port of London'.

variously numbered 31, 32 and 36 - right,

in a drawing from John Adcock Famous London

Houses and Literary Shrines of London (Dent 1912), and

photo of 1920 - which until it was demolished bore a blue plaque. Day's

1773 poem The Dying Negro,

written with John Bicknell, was an early inspiration to the

anti-slavery

campaign, and The

Devoted Legions (1776) argued for the rights of

the American colonists. He is most remembered for his children's book The

History of Sandford and Merton (1783) which

espouses Rousseau's ideals. Far right

is a 1770 portrait by Joseph Wright (National Portrait Gallery). [In

the 1820s and 1830s no.32 was

the home of an engineer, John Hague

(c1781-1857) who registered various patents, including for

sugar-blowing and hydraulic machinery, but was declared bankrupt in

1845, then living at Rotherhithe; it later housed a Jewish hostel.]

Thomas

Day (1748-89), author, politician and disciple

of

Rousseau, though he lived most of later life at the family estate in

Barehill, Berkshire, was born in Wellclose Square, at a house which

went with his father's

job as 'Collector of the Customs Outward in the Port of London'.

variously numbered 31, 32 and 36 - right,

in a drawing from John Adcock Famous London

Houses and Literary Shrines of London (Dent 1912), and

photo of 1920 - which until it was demolished bore a blue plaque. Day's

1773 poem The Dying Negro,

written with John Bicknell, was an early inspiration to the

anti-slavery

campaign, and The

Devoted Legions (1776) argued for the rights of

the American colonists. He is most remembered for his children's book The

History of Sandford and Merton (1783) which

espouses Rousseau's ideals. Far right

is a 1770 portrait by Joseph Wright (National Portrait Gallery). [In

the 1820s and 1830s no.32 was

the home of an engineer, John Hague

(c1781-1857) who registered various patents, including for

sugar-blowing and hydraulic machinery, but was declared bankrupt in

1845, then living at Rotherhithe; it later housed a Jewish hostel.]

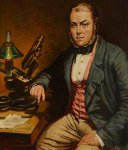

The

next residents of no.50 were

scientists John

Thomas Quekett (1815-61) [right], founder of the Royal

Microscopical Society, and his brother (also a histologist and

miscroscopist) Edwin John

Quekett. They came to live next door to their older brother William

at no.51, who was the first

Vicar of Christ Church Watney Street. Here

is an 1841 paper by Edwin for the Medical Gazette, 'On

the Production of Ergot of Rye'.

The

next residents of no.50 were

scientists John

Thomas Quekett (1815-61) [right], founder of the Royal

Microscopical Society, and his brother (also a histologist and

miscroscopist) Edwin John

Quekett. They came to live next door to their older brother William

at no.51, who was the first

Vicar of Christ Church Watney Street. Here

is an 1841 paper by Edwin for the Medical Gazette, 'On

the Production of Ergot of Rye'.

Dr

Nathaniel

Bagshaw Ward

(1791-1868) invented around 1829 the terrarium or 'Wardian case'

[examples left], a

dry version of

an aquarium, because his ferns were being

poisoned by

the London air. He was the son and assistant of Stephen Smith Ward, who

practised medicine in the Square, and succeeded him in the practice.

Dr

Nathaniel

Bagshaw Ward

(1791-1868) invented around 1829 the terrarium or 'Wardian case'

[examples left], a

dry version of

an aquarium, because his ferns were being

poisoned by

the London air. He was the son and assistant of Stephen Smith Ward, who

practised medicine in the Square, and succeeded him in the practice. Jan

Hendrik [John Henry] Vorstius (1827-1879) was the son of a wealthy Amsterdam

stockbroker - family arms right

- but having settled in London and anglicized his forenames, in 1851

married Charlotte Crawford, née Vardey, a 23-year old widow with a 2

year old son, at St John of Wapping. She was living with her stepfather

William Johnson at 83 St George Street, described in the 1851 census as

a beer seller; Jan/John was

more grandly described in the wedding

register as a licensed victualler.

The had six children, baptized at

St John of Wapping. By 1855 (when their son Alfred Edward was born - he

married in 1871) they were living at no.10

Wellclose Square and he was a cab

proprietor; the same profession was given in the 1871 census,

when they were at 224 St George Street, though in 1861 (at Hill Street)

he was described as a coachman.

What brought him to the area, and why

did he stay? More details here.

Jan

Hendrik [John Henry] Vorstius (1827-1879) was the son of a wealthy Amsterdam

stockbroker - family arms right

- but having settled in London and anglicized his forenames, in 1851

married Charlotte Crawford, née Vardey, a 23-year old widow with a 2

year old son, at St John of Wapping. She was living with her stepfather

William Johnson at 83 St George Street, described in the 1851 census as

a beer seller; Jan/John was

more grandly described in the wedding

register as a licensed victualler.

The had six children, baptized at

St John of Wapping. By 1855 (when their son Alfred Edward was born - he

married in 1871) they were living at no.10

Wellclose Square and he was a cab

proprietor; the same profession was given in the 1871 census,

when they were at 224 St George Street, though in 1861 (at Hill Street)

he was described as a coachman.

What brought him to the area, and why

did he stay? More details here. 1872: an article claimed that a notice at

the entrance to the Prussian Eagle

tavern, in Ship Alley (a meeting-place for Germans, with a

well-used dance hall upstairs, with one of the various

4- or 6-piece

German bands providing music) read All persons are requested,

before entering the dancing saloon, to leave at the bar their pistols

and knives, or any other weapon they may have about them. This

may be a myth, but Melville McNaughton, later Assistant Commissioner at

New Scotland

Yard, recalled visiting as a young constable, when dancing

was carried on by German ladies, and sailors of all nationalities, and

the sight of a drawn knife or two was not infrequent. [1872 map

right shows the various

institutions.]

1872: an article claimed that a notice at

the entrance to the Prussian Eagle

tavern, in Ship Alley (a meeting-place for Germans, with a

well-used dance hall upstairs, with one of the various

4- or 6-piece

German bands providing music) read All persons are requested,

before entering the dancing saloon, to leave at the bar their pistols

and knives, or any other weapon they may have about them. This

may be a myth, but Melville McNaughton, later Assistant Commissioner at

New Scotland

Yard, recalled visiting as a young constable, when dancing

was carried on by German ladies, and sailors of all nationalities, and

the sight of a drawn knife or two was not infrequent. [1872 map

right shows the various

institutions.]

See

here for 1911

and 1934 accounts of the

Square.

See

here for 1911

and 1934 accounts of the

Square.

1967 & 1968:

here are two wistful drawings showing the potential of the Square and

what might have been saved. The first is by Noel Gibson, and the second

by Geoffrey Fletcher who wrote The

devastation of the square was pitiful to see. I only saw one man all

the time I paced the square, and he had one foot in the grave. The

April evening was chill and the sky overcast, but a blackbird warbled

in the plane trees, introducing impromptu variations and evidently

trying to keep his courage up. The half dozen Georgian terraced houses

left on the north side looked indescribably weary and exhausted, their

bricks crumbling and their stucco returning to sand. Grass was coming up on the pavement.

1967 & 1968:

here are two wistful drawings showing the potential of the Square and

what might have been saved. The first is by Noel Gibson, and the second

by Geoffrey Fletcher who wrote The

devastation of the square was pitiful to see. I only saw one man all

the time I paced the square, and he had one foot in the grave. The

April evening was chill and the sky overcast, but a blackbird warbled

in the plane trees, introducing impromptu variations and evidently

trying to keep his courage up. The half dozen Georgian terraced houses

left on the north side looked indescribably weary and exhausted, their

bricks crumbling and their stucco returning to sand. Grass was coming up on the pavement.

The story of the

demolition of the remaining houses, and the 'redevelopment' of the

area, is told here. In a shed at the rear

of no.37 an oak carved

sacrament cupboard or aumbry,

dating from the early 16th century, possibly French in origin, was

found. Right is a still from

'Poppy', a 1975 episode of The

Sweeney,

showing St Paul's School in the background, and a view of the site

between St Paul's School and The Highway where subterranean electrical

cabling [far right] is under

way. Public Projects, a local

network, is campaigning for a creative use

of this site when this work is completed, hoping to build on Tower Hamlets'

new conservation

area of 2008 centred on Wilton's Music Hall and Wellclose

Square. For further comment,

see Will Palin on 'This unfortunate and

ignored locality' in Spitalfields Life (December

2012).

The story of the

demolition of the remaining houses, and the 'redevelopment' of the

area, is told here. In a shed at the rear

of no.37 an oak carved

sacrament cupboard or aumbry,

dating from the early 16th century, possibly French in origin, was

found. Right is a still from

'Poppy', a 1975 episode of The

Sweeney,

showing St Paul's School in the background, and a view of the site

between St Paul's School and The Highway where subterranean electrical

cabling [far right] is under

way. Public Projects, a local

network, is campaigning for a creative use

of this site when this work is completed, hoping to build on Tower Hamlets'

new conservation

area of 2008 centred on Wilton's Music Hall and Wellclose

Square. For further comment,

see Will Palin on 'This unfortunate and

ignored locality' in Spitalfields Life (December

2012).

Homepage | About Us | Services & Events

| Church &

Churchyard |

History

Newsletters & Sermons | Contacts,

Links & Registers | Giving | Picture

Gallery |

Site Map