The Charity

Organisation Society

Much

has been written about the Charity Organisation Society (COS), both

by admirers and critics. Its impact on late Victorian social policy

was strong: its founders were well-connected and familiar with the

corridors of power. Its distinctive approach was by turns

progressive and reactionary:

|

This page traces some of the impact of COS on this and neighbouring parishes. In the 19th century some of our clergy were enthusiastic supporters (one went on to found an American branch); others were hostile and would have nothing to do with it; yet others changed their minds. One of our 20th century Rectors, J.C. Pringle, served for many years as its General Secretary both before and after his time in the parish.

Precursors

Various

charities had been created by the middle classes to address the

effects (though not the causes) of poverty. Among them were the

Strangers' Friend Society

(1785), the Society for the

Suppression of

Mendicity (1818); the

Metropolitan Visiting and Relief Association

(1842); the Society for

Improving the Condition of the Labouring

Classes (1844), whose chairman was Lord Shaftesbury; and the Society

for the Relief of Distress (1860). In 1857 the Social Science

Association (SSA) was established to pursue research into

welfare

issues, including sanitary provision - Octavia Hill was to be a

leading light. In 1866 John Llewelyn Davies, who in the previous

decade had been Vicar of St Mark Whitechapel, published The Poor Law and Charity,

foreshadowing the COS approach.

Foundation

When

attempts to join with other bodies (including SSA) failed, a new

society was created in 1869 at the home of Lord Lichfield. The

rallying-call was a paper read at the Society of Arts the previous

year by a Unitarian minister Henry Solly [left - in 1862 he had

founded the Working Men's Club & Institute], How to Deal with the

Unemployed Poor of London, and with its 'Rough' and Criminal

Classes. Its full title was the

Society for Organising

Charitable Relief and Repressing Mendicity, with 'The Charity

Organisation Society' adopted as the working title in 1870. Among the

founders were Lord Shaftesbury, William Gladstone, John Ruskin,

Cardinal Manning and Octavia Hill, though

her emphasis on subjective

feelings alongside statistical research was to make her influence

marginal. Other key figures were Thomas Mackay, Helen and Bernard

Bosanquet (who wrote London,

its Growth, Charitable Agencies and

Wants

in 1868), and also Canon Samuel Barnett of St Jude Whitechapel

and Charles Booth, both of whom were later to fall out with the

society. Charles Stewart Loch, Balliol-educated son of an Indian judge,

replaced Bernard Bosanquet as general

secretary in 1875. He was just 26; he later married Sophia Peters, one

of Octavia Hill's helpers. He was to be hugely influential, holding the

post

until 1913. His publications included Charity Organisation (1890) and Charity and Social Life

(1910).

When

attempts to join with other bodies (including SSA) failed, a new

society was created in 1869 at the home of Lord Lichfield. The

rallying-call was a paper read at the Society of Arts the previous

year by a Unitarian minister Henry Solly [left - in 1862 he had

founded the Working Men's Club & Institute], How to Deal with the

Unemployed Poor of London, and with its 'Rough' and Criminal

Classes. Its full title was the

Society for Organising

Charitable Relief and Repressing Mendicity, with 'The Charity

Organisation Society' adopted as the working title in 1870. Among the

founders were Lord Shaftesbury, William Gladstone, John Ruskin,

Cardinal Manning and Octavia Hill, though

her emphasis on subjective

feelings alongside statistical research was to make her influence

marginal. Other key figures were Thomas Mackay, Helen and Bernard

Bosanquet (who wrote London,

its Growth, Charitable Agencies and

Wants

in 1868), and also Canon Samuel Barnett of St Jude Whitechapel

and Charles Booth, both of whom were later to fall out with the

society. Charles Stewart Loch, Balliol-educated son of an Indian judge,

replaced Bernard Bosanquet as general

secretary in 1875. He was just 26; he later married Sophia Peters, one

of Octavia Hill's helpers. He was to be hugely influential, holding the

post

until 1913. His publications included Charity Organisation (1890) and Charity and Social Life

(1910).

District

Committees were established; Marylebone, led by Octavia Hill,

was the

first and St George's (East) the second; by 1870 there were

seventeen. There was a constant struggle to recruit enough volunteers to staff

the committees and do the work. Tensions were to surface between

the local and the authoritarian central committee.

Many

of the local clergy were supportive (for a variety of reasons) - for

example, in 1883 the St George's (East) Committee was chaired by the

Rector, with two of his curates, the incumbent of Christ Church and two

of his curates, and the incumbent of St John's with his curate, plus

Wapping clergy, as members - a more overwhelmingly clerical body

than elsewhere (see below on Crowther, its secretary). But other clergy

were opposed to its methods, among them probably Dan Greatorex of St Paul Dock Street. In 1877 Henry Cowell, who had been one of the mission priests at St Saviour's, spoke of the certain stigma

attached to clergy who supported COS, and in 1886 Charles Latimer Marson,

who had been Samuel Barnett's curate at St Jude Whitechapel and was

later involved with various Christian Socialist groups (and also the

collection of folksongs), filled in a mock application form for relief in the name of Jesus Christ [right].

Many

of the local clergy were supportive (for a variety of reasons) - for

example, in 1883 the St George's (East) Committee was chaired by the

Rector, with two of his curates, the incumbent of Christ Church and two

of his curates, and the incumbent of St John's with his curate, plus

Wapping clergy, as members - a more overwhelmingly clerical body

than elsewhere (see below on Crowther, its secretary). But other clergy

were opposed to its methods, among them probably Dan Greatorex of St Paul Dock Street. In 1877 Henry Cowell, who had been one of the mission priests at St Saviour's, spoke of the certain stigma

attached to clergy who supported COS, and in 1886 Charles Latimer Marson,

who had been Samuel Barnett's curate at St Jude Whitechapel and was

later involved with various Christian Socialist groups (and also the

collection of folksongs), filled in a mock application form for relief in the name of Jesus Christ [right].

Its philosophy and practice

Its philosophy and practice

In

a paper read to the SSA in 1869, significantly titled The Importance

of aiding the poor without almsgiving,

Octavia Hill [left in 1870s]

set out what was

to be the approach of COS: charity, which is a work of friendly

neighbourliness, and essentially private, should help and not harm.

Any gift which did not make an individual better, stronger and more

independent damaged rather than helped him. 13 August 2012 saw the

centenary of Ocavia Hill's death, and various events were held to mark it.

Among

the factors influencing leading members (in different proportion for

each) were

| § 'neo-Malthusianism' (especially

Thomas Mackay): the reapplication of

the ideas of the Revd Thomas Robert Malthus,

who argued that poverty, like natural disasters, could have beneficial

effects in

long-term population control (his main target), and that relief

should be left as far as possible to private charity, to motivate the

most able victims of poverty towards self-improvement § the 'classical' economic theories of Thomas Hobbes and Adam Smith as they applied to welfare § fears of social unrest: the labour market had worsened the lot of casual workers, widening the gap between rich and poor, increasing pauperism and the rise of the 'dangerous classes'. COS saw themselves as 'resident gentry' checking these tendencies § in the 1880s and 1890s, the rise of 'socialism' (an issue to which COS generally over-reacted). The 1884 report lamented that socialist ideas were taking a great hold upon the clergy, and that many books were being produced, the title of some of which sound like sentimental novels |

In practice this meant that the COS wanted 'out-relief' (casual individual payments) under the Poor Law system to wither away, with a return to the rationale of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act, restricting help to 'in-relief' of the able-bodied through the workhouses which were set up in each parish (or in unions of parishes) under the control of local Boards of Guardians. (See here for evidence of Abraham Gole, a churchwarden and trustee, on the workings of the system immediately prior to the 1834 Act.) Over the years out-relief had spread, and COS believed this was a corrupting sign of a dysfunctional society. It also meant that the Poor Law Guardians and the charities were competing for the same clients, each knowingly giving inadequate relief because of the other.

Heavily influenced by the COS authorities, the 1869 'Goshen circular' (he was the President of the Central Poor Law Board) instructed local Boards to co-operate with charities so that the Poor Law would relieve the undeserving in workhouses, and charities the deserving, and out-relief be drastically reduced. Although COS had secured many places on the local Boards (knowing how to get their people nominated), most Boards received this coldly - but not St George-in-the-East, where COS had no less than six places and the chairman was Albert Peel. He was a wealthy farmer, Conservative MP for South Leicestershire, and chaired the Central Chamber of Agriculture (a pressure group of rural landowners resisting social change); from 1877-98 he also chaired the Central Poor Law Conference. In St George's (and in due course Whitechapel and Stepney) out-relief virtually disappeared, and the Poor Law Board and COS worked hand-in-hand.

The COS argued that if the Poor Law system concentrated on in-relief of able-bodied males (using the discipline of the workhouse), more 'scientific' charitable provision could be made for those whose value to the labour market was marginal: widows, the elderly, children, the chronically sick and disabled - the traditional 'impotent poor'. On that basis they developed their pattern of individual social casework, aiming to build self-sustaining units that drew on the resources of family, friends, and neighbours (which were assiduously assessed before any grant was made). See this collection of annual reports from 1883, some of which give detailed case studies of those who were assisted and those who were not. From the 1890s they produced training manuals for this purpose, for the use of their volunteers. They also believed that loans (which the Jewish societies used) could be less 'demoralising' than gifts.

Although it never captured the whole of the Poor Law system, COS was highly influential in public debate through the 1870s and 1880s. But by then political and economic crises were pushing the middle classes away from the stern unbending tenets of economic individualism towards more collectivist, 'liberal' remedies. Some members came to see the need for limited extension of state action to address the problems endemic to late Victorian capitalism and the rise of socialist ideas (given greater currency by the extension of the franchise, including to those in receipt of medical relief - who could now have a say in the election of Boards of Guardians!) The issue of pensions proved to be the flashpoint.

Pensions

The

campaign for state pensions

was originally a conservative cause, so

that the Poor Law could revert to its 1834 rationale, and the

able-bodied be dealt with more harshly (as described above). It was

assumed to need contributory insurance funding. In time, however, the

labour movement took up the cause, and argued for non-contributory

old age pensions as an entitlement.

The

COS said no to the idea in its first annual report in 1870 - and

continued to do so. Unsurprisingly, it favoured charitable pensions.

In 1875 the St George's District Committee raised a fund for

'chronic' pensions, for long standing residents: 12s 6d for a couple

and 8s for a single person, supplementing out-relief. This expanded

in 1877 into the Tower Hamlets

Pensions Committee; chaired by Albert

Peel (see above), its members were Canon Barnett, A.G. Crowder*,

Russell Barrington, Charles Fremantle and J.R. Holland. It was to

provide pensions so far as its funds permit, for those poor persons

who seem by their character and circumstances to be worthy of

assistance outside the workhouse. By 1881, it was only issuing

119

pensions, and by 1896 only 1194 (961 of them to women) across the

three Unions of St George's, Whitechapel and Stepney. One reason was

that these pensions had to be 'deserved';

recipients were chosen to

set an example, as the

'cream' of the old working

people in the district. Morality seemed more important than the

relief of poverty, and pensions depended on the usual rigorous

examination of family circumstances, and what help younger relatives

could give. Furthermore, the COS insisted on fresh donations for such

cases, because help should be direct,

to strengthen the human

contact. Deserving cases were advertised in the Charity Organisation

Review, giving personal details. Typically of the organisation,

donations were paid to the Committee, then forwarded to the relevant

district committee, and delivered weekly by a COS visitor.

|

*AUGUSTUS

GEORGE CROWDER He was the Secretary of the local COS branch, and in 1876 became a Poor Law Guardian for St George-in-the-East. In consort with Albert Peel, he set about reforming the Board's work, curtailing out-relief to a minimum - in which he had few imitators. Peel had high regard for him, describing himself as Crowder's disciple. He became secretary of the annual Metropolitan District Poor Law conferences (representing 30 Unions across London), and was made a Justice of the Peace. He was also a member of the Liberty and Property Defence League. By this time he had become a leading member of St George's church (footing the entire bill for the laying-out of St George's Gardens in 1886 by the then-Rector Harry Jones), and closely involved with Christ Church Watney Street. In 1888 his evidence to the House of Lords Select Committee on Poor Law Relief (published as The Administration of the Poor Law Spottiswoode 1888), included these words: If outdoor relief were abolished, charity would receive such an impetus that it would prove sufficient. I think it is the business and duty of the rich to take up cases of deserving distress... it is hopeless to look for much improvement unless the present too wide discretion of the Guardians is curtailed, and by legislation and Orders of the Local Government Board the progress that has already been made is made general and permanent

His

new Rector at St George's, C.H. Turner, also gave evidence along the

same lines: Twenty years later Crowder was still active in the COS, as a representative of the 'hard and dry' strand of opinion, warning in a 1909 report on its future direction that any relaxation of the Society's view regarding the role of the state in social provision would result in increasing amounts of injurious relief given under the guise of co-ordination and co-operation.

Denmark

Street was renamed Crowder Street [right, today] in his memory. In

our parish archives is his annotated map, dated 20 April 1875, of the

boundaries of the Poor Law Parish of St George-in-the East. |

To return to the question of pensions:

COS'

continued opposition to any state intervention through the 1880s

began to seem remote and anachronistic. Charles Booth [left] was the first

COS member to break ranks and advocate a universal, non-contributory

pension of 5s. a week. Canon Samuel Barnett

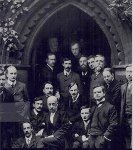

[right, with his wife Henrietta, and with students and others at Toynbee Hall] followed

him. In 'Practical

Socialism' (Nineteenth

Century, April 1883) and later in 'A Friendly

Criticism of the COS' (1895), Barnett said that while he was

glad that

outdoor relief had been virtually abolished, intervention was needed

to address the socialist challenge. He advocated a pension of between

8s. and 10s. a week to every

citizen who had kept himself until the

age of 60 without workhouse aid, with a work test. The COS, he

said,

was refusing to do anything except clothe themselves in the dirty

rags of their own righteousness. [n 1908 Canon Barnett was reported as saying The

working classes are aliens from the Church. They are not antagonistic;

what is perhaps worse, they are indifferent. They are somewhat scornful

of the Church's teaching, and sceptical as to its authority. Few Labour

leaders are Churchmen, and the Church cannot be said to be influential

in the thought of the Labour circles.]

COS'

continued opposition to any state intervention through the 1880s

began to seem remote and anachronistic. Charles Booth [left] was the first

COS member to break ranks and advocate a universal, non-contributory

pension of 5s. a week. Canon Samuel Barnett

[right, with his wife Henrietta, and with students and others at Toynbee Hall] followed

him. In 'Practical

Socialism' (Nineteenth

Century, April 1883) and later in 'A Friendly

Criticism of the COS' (1895), Barnett said that while he was

glad that

outdoor relief had been virtually abolished, intervention was needed

to address the socialist challenge. He advocated a pension of between

8s. and 10s. a week to every

citizen who had kept himself until the

age of 60 without workhouse aid, with a work test. The COS, he

said,

was refusing to do anything except clothe themselves in the dirty

rags of their own righteousness. [n 1908 Canon Barnett was reported as saying The

working classes are aliens from the Church. They are not antagonistic;

what is perhaps worse, they are indifferent. They are somewhat scornful

of the Church's teaching, and sceptical as to its authority. Few Labour

leaders are Churchmen, and the Church cannot be said to be influential

in the thought of the Labour circles.]

Both Booth and Barnett, who hitherto had shared many of the COS presuppositions and were 'reluctant collectivists', were singled out for vicious attack by C.S. Loch and others. Barnett was described as a political coward who kept changing his views. Booth's scheme was seen as the most 'socialistic'; his empirical research, previously approved of by COS, was now dismissed as manipulation and decimal-pointing of all figures within his reach; his shower bath of 5s. pensions would demoralise those who did not need them, and be insufficient for those who did. It was at this point that Beatrice and Sidney Webb also parted company with COS.

Pensions became the social issue of the 1890s, and the campaign increasingly divided COS. Brooke Lambert (also formerly of St Mark Whitechapel) warned that continued opposition, ignoring the growing public support for state pensions, would look foolish. The District Committees resented being dictated to by the Council, and being regarded as disloyal; led by Barnett, several of them protested. But the old guard prevailed for a little longer. Loch spoke of the two paths: one slow and difficult, leading to social independence, prosperity and stability for all; the other, that of liberal political expediency, dangerous, fatally expensive, and resulting in universal pauperisation. (There were double standards at work here, since many of the middle class received occupational pensions! Octavia Hill was trapped into saying that she was against all pensions, but that those paid to higher class people were utterly different.)

Public

support

for a scheme like Booth's was growing. In the 1894 elections COS

lost influence on the Boards of Guardians. In 1896 the COS stance was

attacked in the press. By the time of the 1905-9 enquiry into the

Poor Law, it was too late for COS to speak with credibility on

this issue; the 5s. pension became a reality in 1909. However, Loch's

ideological baton was passed on to his successor J.C. Pringle, who served as general secretary of COS both before and after his time as Rector of St George-in-the-East.

Public

support

for a scheme like Booth's was growing. In the 1894 elections COS

lost influence on the Boards of Guardians. In 1896 the COS stance was

attacked in the press. By the time of the 1905-9 enquiry into the

Poor Law, it was too late for COS to speak with credibility on

this issue; the 5s. pension became a reality in 1909. However, Loch's

ideological baton was passed on to his successor J.C. Pringle, who served as general secretary of COS both before and after his time as Rector of St George-in-the-East.

For a more detailed account of COS and pensions, to which the above is indebted, see chapter 4 of John Macnicol The Politics of Retirement in Britain 1878-1948.

Mansion House Conference on Condition of the Unemployed / Toynbee Hall Executive

In 1892 a conference of the 'great and the good' was held which

concluded that, while the employment situation across London had

improved, there remained particular concerns about waterside labourers

and dock workers (who had mounted a ground-breaking strike in 1889: Cardinal Manning

- one of the founders of COS - was instrumental in effecting a

settlement). Accordingly a local Executive was formed, which met at

Toynbee Hall. The Spectator of 21 December 1892 commented on the letter some of its members sent to The Times:

| The Times of Thursday publishes a letter upon the condition of the unemployed in London signed by seventeen of the most prominent 'friends of the poor', the names including the Rev. S. A. Barnett, the Rev. Marmaduke Hare, the Rev. E. Hoskyns, Mr. Sydney Buxton, Mr. J. Williams Benn, M.P., the Rev. Hugh Price Hughes, Mr. Sidney Webb, Mrs. Webb (Miss Beatrice Potter), and Mr. Charrington. Their account of the situation and their remedy are both unexpectedly moderate. They deny the existence of general want of employment as in 1886, and declare that although grave, it is confined to localities, more especially round the docks; the great strike there having ended in a divergence of business to Tilbury, and in replacing the casuals by regular hands. They earnestly deprecate the creation of any charitable fund whatever, as it only adds to the distress by attracting tramps to London from all England. They recommend that the distressed parishes should find as much work as possible, but should confine it to residents, should exact a full day's work, and should strictly distinguish between the true unemployed and their 'demoralised' comrades, who must ultimately be placed under 'humane discipline'. The parishes should be assisted by a voluntary committee, which should expend, through them, all the charitable subscriptions received. Add to these suggestions that the rate of wages paid for the educating work given by the parishes should always be less than the rate obtainable in open market at ordinary times, and that would be a working scheme. |

The full list of members - a distinguished cast of social reformers - was: Canon Samuel Barnett (warden of Toynbee Hall), J. Williams Benn (Sir John Benn, Liberal MP for St. George's East - and grandfather of the late Tony Benn),

Percy Bunting (a Wesleyan journalist), Sydney Buxton (Liberal MP for Poplar), Corrie Grant (Liberal journalist and barrister, later MP), Rev. Edwyn

Hoskyns (Rector of Stepney), Rev. Hugh Price Hughes (Methodist - pioneer of the Forward Movement), Henry Scott

Holland (Canon of St Paul's Cathedral), Messrs. J. Matthews (Nonconformist Council), George Shipton

(London Trades Council), and W.C. Steadman, LCC (London Trades

Council), Miss Beatrice Webb [Potter], Mr. Sidney Webb, LCC, and Mr. F. N.

Charrington, LCC, Rev. Marmaduke Hare (Rector of Bow), Rev. Peter

Thompson

(East End Wesleyan Mission - he had organised meals for striking

dockers, and let them meet on church premises), Mr. Bolton Smart, Hon.

Sec. (the

last four on behalf of the Great Assembly Hall Conference of East End

ministers of of all denominations), Sir Charles Fremantle KCB (Deputy Master of the Royal Mint), Rev. C.H.

Turner (Rector of St George-in-the-East), and C. S. Loch.

Many

of these supported the COS approach - though as noted above,

disagreements were emerging. The content of their report, proposing a

carefully-supervised public works job creation programme rather than

'dole', certainly reflects COS thinking. Here are some extracts, as

reported in The Times

of 29 December - it was signed by all except the three last

named, who dissented on the cost implications of the proposals. [The

permanent decasualisation of dock labour for which they hoped did not

occur until the 1960s.]

| We

have obtained information from trade societies and employers, from

charitable and from official agencies, and we have submitted our

conclusions to the criticism of workmen, clergymen, members of public

bodies, and the Charity Organisation Society. We find that, although

certain localities are suffering acutely, there is no evidence of any

general lack of employment throughout London as a whole, other than

what is unfortunately usual at this season of the year. The building

trades of the metropolis, employing probably 150,000 operatives, are

exceptionally busy for this time of the year - an exceptional

prosperity which may at any moment be chocked by severe frost. But in

marked contrast to the general evidence we find a consensus of

authoritative testimony that the number of men without employment about

the docks and parts of the riverside, east and south-east of the city,

is considerably greater than is usual at this time of year. The

distress among the labourers in certain eastern and south-eastern

districts is seriously intensified by the lack of employment in the

highly localised shipbuilding and engineering trades, which employ in

London probably 65,000 operatives, whilst it is scarcely mitigated by

the exceptional prosperity of the London building trades, recruited as

those are from skilled mechanics of a distinct class, largely drawn

from the provinces. In some East end districts the distress among

permanent residents is acute and widespread. There is also evidence

that the widely advertised charitable operations of the Salvation Army

and other agencies have, by attracting destitute persons to East

London, increased the local competition for subsistence. [The Rev. H.

Price Hughes dissents from this reference to the Salvation Army.] In short, our independent inquiry exactly confirms the conclusion of Mr. John Burns MP in his article in the Nineteenth Century this month, that Taking London as a whole there is about the average number out of work for this time of year; but, taking groups of trades and districts, as the extreme East end, things are nearly as bad as in 1880. Pointing out that the centre of the area of distress appears to be the docks, the report declares that dock labour, then, in London is affected by two influences, quite apart from the depression in trade, which affects general labour—(1) Its casual labour is in course of elimination. (2) Even some of its regular work is leaving London for Tilbury. The problem of the unemployed, therefore, is twofold. There is a temporary difficulty in obtaining work amongst a certain class of labourers, especially amongst those dependent upon shipping and related industries. More important is it to notice that there is being effected, we may well hope, a permanent decasualisation of labour at the docks. If the essential fact be that the better organisation of labour at the docks is permanently depriving whole classes of their means of subsistence-the temporary provision of work by local authorities affords no solution of the real problem, and, by attracting labourers to the distressed districts, may even intensify the evil. In order to grapple with the main problem, the provision of work for the temporarily workless must, we urge, be used to assist us in dealing more effectually with those whose industry is permanently dislocated. If some scheme of test work could be carried out during this winter, we should have at the end a number of men with whom it would be possible to deal hopefully, and who would have been sifted from the demoralised residuum, who cannot be provided for as bonâ fide unemployed, but whose needs must be met by some humane discipline. We therefore recommend: 1. That when local authorities provide work for the unemployed they should adopt the following rules:—(a) That any work given should be regarded not only as relief, but also as a test of fitness for further help, and should be strictly supervised, so as to insure the performance of a full day's task, (b) That employment be restricted to settled inhabitants of the particular district (excluding the mere 'dosser') who have been resident somewhere in the metropolis for at least a year, (c) That in order to enable permanent help to be eventually given to the applicant if needed, a register be made of (1) name and address of last previous employer, to whom reference will be made when required; (2) all previous occupations of the applicants; (3) report on efficiency and conduct whilst at work for the local authority. Similar regulations should, as far as possible, be adopted by the Government or the County Council in any works undertaken for the relief of distress. 2. That anything of the nature of a 'Mansion-house Fund' for the relief of distress, or any new fund for the irresponsible and indiscriminate provision of meals, lodging, or other doles in the distressed districts would, in our opinion, inflict a cruel injury upon the inhabitants of these districts, and seriously aggravate the disease. 3. That a small voluntary committee should be at once formed to collect and classify the statistics obtained by the local authorities; ascertain by appropriate inquiries which of the unemployed need to be more permanently assisted, and how this can best be done; and administer whatever funds may be subscribed by the public. 4. That this committee make such appeal for funds from the charitable public as may be required from time to time—(1) to supplement, if necessary, the amount to be spent in useful public works by local authorities in exceptionally poor parishes (i.e., where the ratable value per head of population is below the average and the actual rates in the pound are above the average) ; and (2) to aid such men as are manifestly fit to got now occupation in London or elsewhere, either now or after the winter. 5. That any such fund should in no case be distributed as doles, but that as regards localities where no suitable public work offers, the central committee, aided if necessary by local committees, should co-operate with the Metropolitan Public Gardens' Association and other similar bodies in carrying out out useful public work elsewhere. A minority report signed by the three members of the committee who names appear last on the above list offers a friendly protest on what appears to us to be an important point of principle—namely, the provision by vestries and district boards of relief work for the unemployed at the cost of the public rates. This principle, if now generally adopted, is in our opinion likely to have far-reaching and very injurious consequences. |

Other issues

COS maintained its opposition to indiscriminate philanthropy across a

wide range of issues, though in some areas their alternative approach

was

genuinely innovative. For example, the first hospital almoners were probably inspired by

COS. But in 1871 they set up a medical

sub-committee which deplored the fact that 180,000 out-patients were

treated annually at St Bartholomew's Hospital without any enquiry,

and favoured the creation of charitable provident dispensaries and

after-care centres (especially for TB patients) - see here for the Leman Street dispensary. On 23 March 1878

A.G. Crowder wrote to the British

Medical Journal (which endorsed his views) about the

London Hospital's financial difficulties, claiming that many people

failed to subscribe because of its pertinaceous

neglect of reform....

A system of enquiry into the circumstances of each applicant ought

surely to be adopted. Persons found to be in a position to contribute

towards the cost of their treatment should be made to do so; and

those who have received parish relief, unless requiring special

treatment, should be referred to the workhouse infirmaries. I know,

from my own experience, that the London Hospital, for instance,

habitually admits what may be termed ordinary 'pauper'

cases requiring no special treatment, and that persons suffering from

ordinary illnesses exchange the workhouse infirmaries for that

hospital with impunity. The plan suggested would augment the funds,

obviate the necessity of refusing admission to many legitimate cases

for whom at present there is frequently no room, and also tend to

encourage thrift.

A similar committee was set

up to consider work with the 'physically

and mentally defective' which pressed for better charitable provision

for the blind, and for the mentally ill. For children, the Invalid

Children's Aid Association was created. But, not surprisingly,

COS

opposed the spread of free school meals [compare the approach of Dan Greatorex at St

Paul's Dock Street where they were pioneered]. A

Sanitary Aid Committee was

created in 1882, and some local inspectors

appointed, which helped to raise standards of hygiene. To assist the

able-bodied to find work, they created a series of employment enquiry

offices (the precursor of Labour Exchanges). And they provided

reading rooms (including the Denison Club at Denison House*, Vauxhall Bridge Road, which

became the COS headquarters in 1905), thrift clubs (run by a

thrift sub-committee) and the like.

| * Edward Denison was one of the founders of the Society for the Relief of Distress, son of the Bishop of Salisbury, nephew of the Speaker of the House of Commons and for a short time an MP, but died of TB at the age of 30. He regretted the absence of the middle classes from the East End and the influence they could have, and lived in Philpot Street [north of Commercial Road] for eight months to make his point. His research and example influenced early COS thinking, and J.C. Pringle later referred to him as 'our patron saint'. |

Twentieth

Century

In

1910 the phrase in its title 'for Organising Charitable Relief and

Repressing Mendicity' was replaced by 'for Organising Charitable

Effort and Improving the Condition of the Poor'. C.S. Loch, who had

received honorary degrees from Oxford and St Andrew's in 1905, and a

portrait by the American artist John Singer Sargent RA presented at Lambeth Palace to mark

his 25

years of service [right],

and a knighthood in 1915, retired in

1913. He died ten years later: The Times obituary commented He made the COS - he was the COS.

In 1898 the architect Charles Voysey (whose

'defrocked' father had once been a curate at St Mark Whitechapel) had designed a house

for him at Oxshott [right], on a scale unimaginable for the clients of COS -

but it was never built.

In

1910 the phrase in its title 'for Organising Charitable Relief and

Repressing Mendicity' was replaced by 'for Organising Charitable

Effort and Improving the Condition of the Poor'. C.S. Loch, who had

received honorary degrees from Oxford and St Andrew's in 1905, and a

portrait by the American artist John Singer Sargent RA presented at Lambeth Palace to mark

his 25

years of service [right],

and a knighthood in 1915, retired in

1913. He died ten years later: The Times obituary commented He made the COS - he was the COS.

In 1898 the architect Charles Voysey (whose

'defrocked' father had once been a curate at St Mark Whitechapel) had designed a house

for him at Oxshott [right], on a scale unimaginable for the clients of COS -

but it was never built.

Helen Bosanquet, one

of the COS founders, wrote in 1914 that its work of persistently fastening

on weaknesses in social provision was gradually coming to fruition

(Social

Work in London 1869-1912, pages

266-300); others believed that its stance was becoming

increasingly irrelevant. A questionnaire to clergy in 1916 produced a

half-hearted response (for example, Arthur Stevens, Vicar of Christ Church Watney Street,

said that as he was leaving the parish any answers would be

misleading). But with J.C. Pringle as its new chief officer [see above], and the driving force in the inter-war years, it

continued to produce research and reports, and to challenge policy. Madeline Rooff [see below] said that by upholding its

traditional stance he put the COS at the centre and out of touch with political reality,

though she also notes a growing co-operation with statutory provision,

and feels it came closest to its vocation as an auxiliary service in

this period. And

there were further innovations: in

1938 COS was responsible for the first Citizens'

Advice Bureau,

and

continued to run branches until the 1970s. With 30 district offices at

the outbreak of World War II, it felt no need of a radical re-think of

its philosophy.

Helen Bosanquet, one

of the COS founders, wrote in 1914 that its work of persistently fastening

on weaknesses in social provision was gradually coming to fruition

(Social

Work in London 1869-1912, pages

266-300); others believed that its stance was becoming

increasingly irrelevant. A questionnaire to clergy in 1916 produced a

half-hearted response (for example, Arthur Stevens, Vicar of Christ Church Watney Street,

said that as he was leaving the parish any answers would be

misleading). But with J.C. Pringle as its new chief officer [see above], and the driving force in the inter-war years, it

continued to produce research and reports, and to challenge policy. Madeline Rooff [see below] said that by upholding its

traditional stance he put the COS at the centre and out of touch with political reality,

though she also notes a growing co-operation with statutory provision,

and feels it came closest to its vocation as an auxiliary service in

this period. And

there were further innovations: in

1938 COS was responsible for the first Citizens'

Advice Bureau,

and

continued to run branches until the 1970s. With 30 district offices at

the outbreak of World War II, it felt no need of a radical re-think of

its philosophy.

In 1946 the society was renamed the Family Welfare Association; it had begun to employ paid local staff. In 1975 it pioneered family therapy. The most recent name change was in 2008, when it became Family Action. In the current climate of collaboration between the statutory and voluntary sectors, it is now a leading provider of support to disadvantaged families.

For more information, see Charles

Loch Mowat The Charity Organisation Society

1869-1913 (1961), Madeline Rooff A Hundred Years of Family Welfare: A Study of the Family Welfare Association (Formerly Charity Organisation Society) 1869–1969 (Michael Joseph 1972) and Jane Lewis The

Voluntary Sector, the State and

Social Work in Britain (Brookfield 1995). Michael J.D. Roberts, in an article 'Charity

Disestablished? The Origins of the Charity Organisation Society

Revisited, 1868-1871' in the Journal of

Ecclesiastical History (CUP

2003, vol 54 pp40-61) suggests that alongside the desire to relieve

chronic urban poverty, another key factor in the foundation of COS was

the concern of Whig Broad Churchmen (such as Barnett, and clergy

of St Mark Whitechapel) to fly the flag of religious voluntarism

in the wake of the disestablishment of the Irish church by Gladstone in

1868 (though Gladstone was himself one of the COS founders).

All in all, a complex story!

Back to History page