Methodists ~ The Salvation Army

<<

Dissenters

& Nonconformists (1) |

<< Dissenters

& Nonconformists (2) | Dissenters

& Nonconformists (4) >>

'The world is my parish'

John

Wesley

(1703-91) preached often in the East End throughout his long life and

ministry. According to his diary, on Sunday 1 October 1738 he was at St

George-in-the-East for both the morning and afternoon services,

and adds that on the following days

I endeavoured to explain the way of salvation to many who had

misunderstood what had been preached concerning it. He

records that he was with his brother Charles in the early morning

singing and reading letters. They walked together and breakfasted at Mr

Parker's in Wapping at 9am. At 10am he read prayers, preached and

administered holy communion at St George's; dined at Mr H's [name left

blank] before returning to St George's to read the prayers, preach and

baptize. His schedule for the rest of the day was full: At

4.30 at Mrs Ironmonger's, many tarried, tea, conversed, prayer; 5.30 Mr

Sims' singing &c; 7.15 Mrs Sims', singing, supper, prayer; 8.45 at

home, singing &c; 11 prayer, conversation; 12. 'Home' probably refers to Mr Bray's in Little Britain, where he and Charles were staying.

John

Wesley

(1703-91) preached often in the East End throughout his long life and

ministry. According to his diary, on Sunday 1 October 1738 he was at St

George-in-the-East for both the morning and afternoon services,

and adds that on the following days

I endeavoured to explain the way of salvation to many who had

misunderstood what had been preached concerning it. He

records that he was with his brother Charles in the early morning

singing and reading letters. They walked together and breakfasted at Mr

Parker's in Wapping at 9am. At 10am he read prayers, preached and

administered holy communion at St George's; dined at Mr H's [name left

blank] before returning to St George's to read the prayers, preach and

baptize. His schedule for the rest of the day was full: At

4.30 at Mrs Ironmonger's, many tarried, tea, conversed, prayer; 5.30 Mr

Sims' singing &c; 7.15 Mrs Sims', singing, supper, prayer; 8.45 at

home, singing &c; 11 prayer, conversation; 12. 'Home' probably refers to Mr Bray's in Little Britain, where he and Charles were staying.

This was shortly after his return from the United States, and several months before he submitted to be more vile (as he put it) and follow Whitefield's example of 'field preaching' in the open air - from which point he began to attract large crowds.

In

1742 he preached at Ratcliffe

Square [now Ratcliffe Cross Street], and on ten occasions at St Paul's

Shadwell. The last was on 24 October 1790, at the age of 87,

five

months before his death; his Journal

records St

Paul's Shadwell was....crowded in the afternoon, while I enforced that

important truth 'One thing is needful' and I hope that many even then

resolved to choose the better part. George Wolff of Wellclose Square, the Danish-Norwegian consul and a convert to Methodism, was one of his executors - see here for more details.

On 4 February 1739 George Whitefield

preached at St George-in-the-East. He, like Wesley, was an Anglican

minister, and in some ways a fellow-founder of Methodism, responsible

for the 'Great Awakening' in the United States, but they had a

fundamental theological disagreement - Wesley was Arminian and

Whitefield Calvinist (and so allied to the Countess of Huntingdon's

Connexion - see below). Here is the account from his diary (as edited

by Luke Tyerman in the 19th century) of a momentous day, before he

returned to the USA:

On 4 February 1739 George Whitefield

preached at St George-in-the-East. He, like Wesley, was an Anglican

minister, and in some ways a fellow-founder of Methodism, responsible

for the 'Great Awakening' in the United States, but they had a

fundamental theological disagreement - Wesley was Arminian and

Whitefield Calvinist (and so allied to the Countess of Huntingdon's

Connexion - see below). Here is the account from his diary (as edited

by Luke Tyerman in the 19th century) of a momentous day, before he

returned to the USA:

|

1739. Sunday,

February 4. Preached in the morning at St. George's in the East;

collected £18 for the Orphan House [Bethesda, the oldest charity in North America]; and had, I believe, six hundred

communicants, which highly offended the officiating curate. Preached

again at Christ Church, Spitalfields; and gave thanks and sang

psalms at a private house. Went thence to St. Margaret's Westminster*;

but, something breaking belonging to the coach, could not get

thither till the middle of the prayers. Went through the people to

the minister's pew, but, finding it locked, I returned to the vestry

till the sexton could be found. Being there informed that another

minister intended to preach, I desired several times that I might go

home. My friends would by no means consent, telling me I was

appointed by the trustees to preach; and that, if I did not, the

people would go out of the church. At my request, some went to the

trustees, churchwardens, and minister; and, whilst I was waiting for

an answer, and the last psalm was being sung, a man came, with a wand

in his hand, whom I took for the proper church officer, and told me I

was to preach. I, not doubting but the minister was satisfied,

followed him to the pulpit, and God enabled me to preach with greater

power than I had done all the day before. |

*

There are alternative versions of what happened here, most of them

involving more confrontation, and violence, that Whitefield

acknowledges, and resulting in opposition to his preaching elsewhere.

St George's Wesleyan Methodist (Centenary) Chapel

A

society of worshippers in the East End was established in 1746. In 1812

they built a chapel, seating 1100, to the east of where St George's Town Hall

now stands in Cable Street, and the burial ground soon after. Right is

an 1840 advertisement for 'St George's East

Cemetery' ['New Road' was then part of Cable Street, rather than the

northern extension of Cannon Street Road]; it stresses the security of

the site, with high walls and railings, and resident minister and

sexton. Exclusive and perpetual rights of burial in any plot could be purchased, with moderate terms for common interments. But, as with the parish churchyard, burials ceased in 1854 following the 1852 Metropolitan Burial Act which created public

cemeteries. In 1876 the Vestry bought the

burial ground for £2,700 and incorporated it into St George's Gardens.

A

society of worshippers in the East End was established in 1746. In 1812

they built a chapel, seating 1100, to the east of where St George's Town Hall

now stands in Cable Street, and the burial ground soon after. Right is

an 1840 advertisement for 'St George's East

Cemetery' ['New Road' was then part of Cable Street, rather than the

northern extension of Cannon Street Road]; it stresses the security of

the site, with high walls and railings, and resident minister and

sexton. Exclusive and perpetual rights of burial in any plot could be purchased, with moderate terms for common interments. But, as with the parish churchyard, burials ceased in 1854 following the 1852 Metropolitan Burial Act which created public

cemeteries. In 1876 the Vestry bought the

burial ground for £2,700 and incorporated it into St George's Gardens.

In 1845 Zilpha Elaw [left], a black American woman preacher, visited the church.

A day school was established in the schoolroom; McGill's 1861 census states that it had about 150 pupils. Until

the mid 19th century it was a flourishing chapel, but encountered difficulties

as the

neighbourhood changed. From time to time they had to ask for some

financial help from other circuits, though they did manage to

install, and pay for, hot water and toilets in 1876, when George Curnock

(1817-87) was the minister. As a young man in Bristol he had become a keen

advocate of temperance - he would later say that he found being

teetotal hard at first, and had been advised to take stimulants to

continue with his work. He produced The Railway Navigator: Or, Recollections of Robert Blake, who was Killed by a Fall of Earth on the Tiverton Road Line, March 8th, 1847,

which was later distributed as a Wesleyan Temperance Tract. Before

coming to London, Curnock had ministered in Hulme, Manchester (where he

acted as 'precentor' at the District Synod, starting the hymn tunes),

Huddersfield,

and Leicester - whence he organised a trip to Rome, where the group

met Ferdinando Bosio, an Italian Methodist minister, and held a service

in his mission room. He became a popular Wesleyan preacher.

In 1845 Zilpha Elaw [left], a black American woman preacher, visited the church.

A day school was established in the schoolroom; McGill's 1861 census states that it had about 150 pupils. Until

the mid 19th century it was a flourishing chapel, but encountered difficulties

as the

neighbourhood changed. From time to time they had to ask for some

financial help from other circuits, though they did manage to

install, and pay for, hot water and toilets in 1876, when George Curnock

(1817-87) was the minister. As a young man in Bristol he had become a keen

advocate of temperance - he would later say that he found being

teetotal hard at first, and had been advised to take stimulants to

continue with his work. He produced The Railway Navigator: Or, Recollections of Robert Blake, who was Killed by a Fall of Earth on the Tiverton Road Line, March 8th, 1847,

which was later distributed as a Wesleyan Temperance Tract. Before

coming to London, Curnock had ministered in Hulme, Manchester (where he

acted as 'precentor' at the District Synod, starting the hymn tunes),

Huddersfield,

and Leicester - whence he organised a trip to Rome, where the group

met Ferdinando Bosio, an Italian Methodist minister, and held a service

in his mission room. He became a popular Wesleyan preacher.

In 1874

the new

Metropolitan Lay Mission provided a worker, to undertake district

visiting; Curnock set up a Mission Band and in 1882-3 they visited 520

houses every Sunday. He held open air services and class meetings,

and set up a mothers' meeting. When the grant was withdrawn in 1884,

the congregation managed to pay him for a further year. In 1881 he was a committee member organising a major Œcumenical Methodist Conference

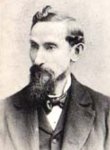

(with American participation) at City Road Chapel. Nehemiah Curnock

(1840-1915), right, transcriber and editor of the standard abridged edition of

John Wesley's Journal, was a relative (? uncle).

In 1874

the new

Metropolitan Lay Mission provided a worker, to undertake district

visiting; Curnock set up a Mission Band and in 1882-3 they visited 520

houses every Sunday. He held open air services and class meetings,

and set up a mothers' meeting. When the grant was withdrawn in 1884,

the congregation managed to pay him for a further year. In 1881 he was a committee member organising a major Œcumenical Methodist Conference

(with American participation) at City Road Chapel. Nehemiah Curnock

(1840-1915), right, transcriber and editor of the standard abridged edition of

John Wesley's Journal, was a relative (? uncle).

In

the 1886 Religious Census of London, which lists Thomas Dixon as the minister,

attendances were listed as 281 in the morning and 399 in the evening.

In

1885 Conference established the London Wesleyan Methodist Mission, as

a response to the spiritual destitution of London and the need for new

ways of working in the light of George Mearn's 1883 broadside The Bitter Cry of Outcast London -

which included many local references, including women and young

children making sacks for a farthing a time. One controversial

provision was the

waiving of the normal 'itinerancy' rule that ministers should move on

every three years, to enable continuity in areas where lay leadership

was weak. They chose the well-nigh forlorn hope [despite the

above figures!] of

St George's

Wesleyan Chapel as their base, and the Revd Peter Thompson

[left] was

stationed here, living at 242 Cable Street. (Charles Edward Robb,

living with his family in Pell Street, was the housekeeper.) Although

in the coming years there was pressure for

radically new

patterns of mission and ministry – such as Hugh Price Hughes' Forward Movement – for the most part existing structures were

retained

and

strengthened. The range of activities - including a Boys Brigade

branch (meeting in Wellclose Square), a Dorcas

Society, a girls' sewing class, a maternity society, a training home

for girls, reading rooms, and the distribution of soup, coffee and

clothing, as well as renewed worship

-

was impressive, but not new in

principle (and mirrored Anglican provision). Weekly rather than quarterly collections were introduced,

a quarterly morning communion was introduced for those who could not

attend in the evening, and temperance work

continued. Thompson was instinctively

a

paternalist, but he was a member of the Anti-Sweating League, and

preached during the 1895 elections on 'Am I my brother's

keeper?'

In

1885 Conference established the London Wesleyan Methodist Mission, as

a response to the spiritual destitution of London and the need for new

ways of working in the light of George Mearn's 1883 broadside The Bitter Cry of Outcast London -

which included many local references, including women and young

children making sacks for a farthing a time. One controversial

provision was the

waiving of the normal 'itinerancy' rule that ministers should move on

every three years, to enable continuity in areas where lay leadership

was weak. They chose the well-nigh forlorn hope [despite the

above figures!] of

St George's

Wesleyan Chapel as their base, and the Revd Peter Thompson

[left] was

stationed here, living at 242 Cable Street. (Charles Edward Robb,

living with his family in Pell Street, was the housekeeper.) Although

in the coming years there was pressure for

radically new

patterns of mission and ministry – such as Hugh Price Hughes' Forward Movement – for the most part existing structures were

retained

and

strengthened. The range of activities - including a Boys Brigade

branch (meeting in Wellclose Square), a Dorcas

Society, a girls' sewing class, a maternity society, a training home

for girls, reading rooms, and the distribution of soup, coffee and

clothing, as well as renewed worship

-

was impressive, but not new in

principle (and mirrored Anglican provision). Weekly rather than quarterly collections were introduced,

a quarterly morning communion was introduced for those who could not

attend in the evening, and temperance work

continued. Thompson was instinctively

a

paternalist, but he was a member of the Anti-Sweating League, and

preached during the 1895 elections on 'Am I my brother's

keeper?'

A

major innovation, however, was to hire secular premises as new-style

mission halls, and in 1891 the Mission took over Wilton's Music Hall,

whose story is told here. It

was known as the 'Old Mahogany Mission'. For

further details, see Margaret Jones, 'New

Creation' in

the East End Mission 1885-97.

She uses the record books, and the

Mission's magazineThe East End (started in 1894)

as evidence. The mission also took over 'Paddy's Goose', as the White Swan public house and music hall along The Highway was popularly known. Frederick James Edwards was assigned to the Mission for a time during this period.

A

generation later, St George's was one of several East End missions to

provide cinematographic entertainment, introduced by the Revd Frederick William

Chudleigh [left]. There were few entertainments available to

working-class

youngsters, and motion pictures proved more popular than magic

lanterns! See Luke McKernan, 'Diverting Time: London’s Cinemas

and

Their Audiences, 1906–1914' in The

London Journal,

vol.32 no.2 (July 2007). See here for details of Cable Picture Palace (1913-40), at 101-105 Cable Street.

A

generation later, St George's was one of several East End missions to

provide cinematographic entertainment, introduced by the Revd Frederick William

Chudleigh [left]. There were few entertainments available to

working-class

youngsters, and motion pictures proved more popular than magic

lanterns! See Luke McKernan, 'Diverting Time: London’s Cinemas

and

Their Audiences, 1906–1914' in The

London Journal,

vol.32 no.2 (July 2007). See here for details of Cable Picture Palace (1913-40), at 101-105 Cable Street.

As Warden of the East End Mission [advertisement right, fromThe Children's Newspaper 28 March 1931], Fred

Chudleigh (1872-1932) was a well-known and popular missioner, with

thousands of East Enders lining the route at his funeral - see his

biography by R.G. Burnett Chudleigh: A Triumph of Sacrifice

(Epworth 1932). He was a socialist, and member of the Independent

Labour Party, writing the foreword to a collection of essays on Christ and Labour

(Jarrold 1912), edited by Charles George Ammon, Labour MP for

Camberwell and later Baron Ammon; he was also a scoutmaster with the National Peace Scouts, who had broken away from the 'militaristic' Baden-Powell organisations (compare the Woodcraft Folk,

which had similar origins within the Co-operative movement). Initially

he supported, and the Mission housed, the work of Pastor Kamal

Chunchie, who had worked with Lascars in the area, in setting up a

centre, the Coloured Men's Institute, for the black and Asian

communities, but they disagreed over strategy (the centre was somewhat

separatist), and new links developed with the Presbyterian church in

Canning Town.

As Warden of the East End Mission [advertisement right, fromThe Children's Newspaper 28 March 1931], Fred

Chudleigh (1872-1932) was a well-known and popular missioner, with

thousands of East Enders lining the route at his funeral - see his

biography by R.G. Burnett Chudleigh: A Triumph of Sacrifice

(Epworth 1932). He was a socialist, and member of the Independent

Labour Party, writing the foreword to a collection of essays on Christ and Labour

(Jarrold 1912), edited by Charles George Ammon, Labour MP for

Camberwell and later Baron Ammon; he was also a scoutmaster with the National Peace Scouts, who had broken away from the 'militaristic' Baden-Powell organisations (compare the Woodcraft Folk,

which had similar origins within the Co-operative movement). Initially

he supported, and the Mission housed, the work of Pastor Kamal

Chunchie, who had worked with Lascars in the area, in setting up a

centre, the Coloured Men's Institute, for the black and Asian

communities, but they disagreed over strategy (the centre was somewhat

separatist), and new links developed with the Presbyterian church in

Canning Town.

Sister

Doris, a Deaconess, came to work here in 1940, when the Revd Tom

Collins was working at the Old Mahogany Bar (ironically for a

Methodist, his name was that of a popular cocktail of the time!) and

the Revd Edward Harland was in charge of St George's Chapel. Here are some memories of her arrival, and the following is an account of a later incident:

|

I was working as a Methodist Deaconess at St George’s, Cable Street, in the east end of London in 1940. One Tuesday afternoon when the Sisterhood was over and the ladies had dispersed, I was busy clearing up and folding the second hand clothes that we had for sale on the stall, to put away into the cupboard, when Mrs. Burgoyne turned up. This was most unusual, as she had not attended the meeting. She had come to tell me that her husband had died in the shelter overnight. I talked with her, and decided to go with her to her flat and see the insurance book which she had in her husband’s name. It was a very poor “book”, with extremely few entries, a shilling here and there. It was obvious that it would not yield any substantial amount for a funeral. This was clearly a case where the Council would have to take responsibility. However, Mrs. Burgoyne’s chief concern lay elsewhere. She said, and kept saying, “I must have my little bit of black!” Whether she ever got her “little bit of black”, I have no idea. As it was well on into the evening I suggested that she get her night’s rest and I would be with her at 8.30 a.m. the next day. I requested that she did not do anything until I arrived. To my surprise, the next morning I discovered that Mrs. Burgoyne had been to the undertaker and had set in motion the funeral arrangements. I had to go to that gentleman and explain the financial situation. He soon realised that it would be a case for the Council, or he would be faced with a bad debt. So it transpired that poor Mr. Burgoyne had to suffer the indignity of being transferred from a private, to a Council coffin when the men came round to collect the body! In due time notice was received of the place and time of the funeral, and that transport for four would be provided. On the day, the minister, Mr. Harland, went to conduct the service, together with Mrs. Burgoyne and her friend, and a Salvation Army officer. When the party was returning Mr. Harland indicated to the driver that he would like to get out at the Church, but Mrs. Burgoyne protested, “You don’t want to get out here, the paper said that there would be provision for four!” For her that obviously meant food! |

Most

of the premises [left - next to the Town Hall] collapsed

in the early 1960s, but the congregation

continued to care for those in need locally, especially the homeless

and dispossessed. They offered a

kitchen and soup run, and medical care, and the premises were used for

a film on homelessness. The Revd Eugene (Gene) W. Morse,

from Missouri, was

stationed here from 1974-78; before his arrival, he was minister of

Winchester United Methodist Church, and received a Bahelor of Divinity

degree from St Paul's School of Theology, Kansas City. Having lived in

the Mission at 583 Commerical Road and working particularly at the

Men's Care Centre on Cable Street, Gene and his wife Lettie, now living

in St Louis, Missouri (where until retirement in 2005 he was executive

director of Kingdom House, providing child care facilities), have

recently been in touch. On a recent visit to London they spent three

nights at their former home - now a hotel - and found that much had

changed, but some things had not!

Most

of the premises [left - next to the Town Hall] collapsed

in the early 1960s, but the congregation

continued to care for those in need locally, especially the homeless

and dispossessed. They offered a

kitchen and soup run, and medical care, and the premises were used for

a film on homelessness. The Revd Eugene (Gene) W. Morse,

from Missouri, was

stationed here from 1974-78; before his arrival, he was minister of

Winchester United Methodist Church, and received a Bahelor of Divinity

degree from St Paul's School of Theology, Kansas City. Having lived in

the Mission at 583 Commerical Road and working particularly at the

Men's Care Centre on Cable Street, Gene and his wife Lettie, now living

in St Louis, Missouri (where until retirement in 2005 he was executive

director of Kingdom House, providing child care facilities), have

recently been in touch. On a recent visit to London they spent three

nights at their former home - now a hotel - and found that much had

changed, but some things had not!

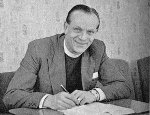

Ronald (Ron) Gibbins was the Superintendent of the East End Mission from 1964 [right, greeted on appointment by Mgr Derek Worlock - on the right - then of SS Mary & Michael,

Commercial Road, later Archbishop of Liverpool, a keen ecumenist

working closely with Bishop David Sheppard]. In 1949 Gibbins, born in

1922, formerly an RAF gunner, had ran a 'back to church' campaign, and

was apparently banned from various pubs and working men's clubs in the

north-east and London because, said the Licensed Victuallers

Association, he

was likely to cause breaches of the peace, and also interfere with

business ... he had been drinking lemonade in public houses, handing

round religious

leaflets, and singing hymns at the piano. At the height of Beatlemania, Gibbins told reporters that a Fab Four version of 'O come, all ye faithful' might provide the church with the very shot in the arm it needs. From 1979 he was minister of Wesley's Chapel,

the 'mother church of world Methodism' in the City, and active in

international Methodist affairs (and also commenting on freemasonry -

Methodists are not barred from joining, he said, but secrecy of any kind is destructive of fellowship).

In 2012, aged 90, he gave an address 'Hopes for Marriage' at the

wedding of his grandson Seth Lakeman (a folk music star)'s

wedding in Cornwall. He died in September 2015.

Ronald (Ron) Gibbins was the Superintendent of the East End Mission from 1964 [right, greeted on appointment by Mgr Derek Worlock - on the right - then of SS Mary & Michael,

Commercial Road, later Archbishop of Liverpool, a keen ecumenist

working closely with Bishop David Sheppard]. In 1949 Gibbins, born in

1922, formerly an RAF gunner, had ran a 'back to church' campaign, and

was apparently banned from various pubs and working men's clubs in the

north-east and London because, said the Licensed Victuallers

Association, he

was likely to cause breaches of the peace, and also interfere with

business ... he had been drinking lemonade in public houses, handing

round religious

leaflets, and singing hymns at the piano. At the height of Beatlemania, Gibbins told reporters that a Fab Four version of 'O come, all ye faithful' might provide the church with the very shot in the arm it needs. From 1979 he was minister of Wesley's Chapel,

the 'mother church of world Methodism' in the City, and active in

international Methodist affairs (and also commenting on freemasonry -

Methodists are not barred from joining, he said, but secrecy of any kind is destructive of fellowship).

In 2012, aged 90, he gave an address 'Hopes for Marriage' at the

wedding of his grandson Seth Lakeman (a folk music star)'s

wedding in Cornwall. He died in September 2015.

The day centre building failed in 1989, and with it most sources of statutory funding and trust giving. One of their final projects, in 1992 (when Ian Hamilton was the minister) was the Cable Street Club for up to 16 latchkey kids. Eventually, the site was sold for private housing. Baptismal registers for 1812-37 and burial registers for 1828-54 are held at the Public Records Office, and baptismal registers for 1838-1910 at the London Metropolitan Archives.

Footnote:

a Methodist quack

Footnote:

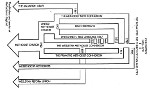

a Methodist quack John

Wesley predicted that there would be many splits and regroupings within

Methodism once it became a separate denomination, and so it proved - see the diagram left!

Most were on matters, not of doctrine, but of church order and

worship (including one over the use of organs). The Protestant

Methodists split in 1827 (Leeds was their centre), and in 1836 the

Wesleyan Methodist Association (with 20,000 members, centred on

Manchester). These two groups amalgamated under the latter title, and

in 1857 joined others

who had seceded in 1849 under the leadership of James Everett,

following the expulsion of some ministers on a charge of

insubordination; they then took

the name United Methodist Free Church.

Their chapels tended to be quite imposing, on a par with the Wesleyan

ones, and often had grand organs (they produced their own hymnal in

1889) and 'graded' pews; their ministers were well-educated, and served

on a pattern similar to the Wesleyans - an initial twelve months,

extended to 3-4 years by invitation of the local quarterly meeting; see here for a note on their college in Manchester.

They were active in foreign missions, especially in China.

John

Wesley predicted that there would be many splits and regroupings within

Methodism once it became a separate denomination, and so it proved - see the diagram left!

Most were on matters, not of doctrine, but of church order and

worship (including one over the use of organs). The Protestant

Methodists split in 1827 (Leeds was their centre), and in 1836 the

Wesleyan Methodist Association (with 20,000 members, centred on

Manchester). These two groups amalgamated under the latter title, and

in 1857 joined others

who had seceded in 1849 under the leadership of James Everett,

following the expulsion of some ministers on a charge of

insubordination; they then took

the name United Methodist Free Church.

Their chapels tended to be quite imposing, on a par with the Wesleyan

ones, and often had grand organs (they produced their own hymnal in

1889) and 'graded' pews; their ministers were well-educated, and served

on a pattern similar to the Wesleyans - an initial twelve months,

extended to 3-4 years by invitation of the local quarterly meeting; see here for a note on their college in Manchester.

They were active in foreign missions, especially in China. |

ST GEORGE'S WESLEYAN FREE CHURCH SCHOOL CANNON STREET ROAD The anniversary meeting was held 21st October. The meeting was large and platform well filled, Robert Charles, jun., Esq. in the chair. The report was very encouraging. There are 448 scholars on the books, and 38 teachers, 36 of whom are church members. The divine blessing had accompanied the labours of the teachers: in the past year several scholars were converted. The first class girls is large, and all are avowedly Christian. Of the first class males, seven-tenths have given their hearts to Jesus. One teacher had had his earnest prayers and strivings answered by the conversion of nine of his scholars. The prayer meetings have been numerously attended, and great earnestness shewn. One child had been instrumental in leading its parent to the Saviour. The secretary, who had filled that office thirty-eight years, had been compelled to resign, having removed to a distance. A children's service is conducted, at which about 100 attend. |

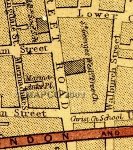

In 1864 the AGM of the Wesleyan Methodist Local Preachers'

Mutual-Aid Association was held at the chapel, reporting on its usual course of usefulness

as an almoner of the Methodist Churches; it had 2254 members (416 honorary) and made

total payments in the year of £2055 (sickness, annuities and funeral costs). The chapel is shown on this 1868 map. By 1871 it had become St George's United Methodist Free Church (when the Sunday School presented to the senior superintendent a handsome

Timepiece and to the senior secretary Dr Adam Clarke's 'Commentary', in six volumes).

In 1878 they moved to new premises, also in Cannon Street Road, which

were licensed for worship and registered for marriages; the former

chapel was demolished.

In 1864 the AGM of the Wesleyan Methodist Local Preachers'

Mutual-Aid Association was held at the chapel, reporting on its usual course of usefulness

as an almoner of the Methodist Churches; it had 2254 members (416 honorary) and made

total payments in the year of £2055 (sickness, annuities and funeral costs). The chapel is shown on this 1868 map. By 1871 it had become St George's United Methodist Free Church (when the Sunday School presented to the senior superintendent a handsome

Timepiece and to the senior secretary Dr Adam Clarke's 'Commentary', in six volumes).

In 1878 they moved to new premises, also in Cannon Street Road, which

were licensed for worship and registered for marriages; the former

chapel was demolished.

For that year (1843) only, the minister was William Harland

(1801-80) - a Yorkshireman and a popular 'Ranter preacher' among the

seafarers and fishermen of the East coast where most of his 43-year

ministry was exercised, but whom (like others just-mentioned)

Conference sent to London, where he was Superintendent of the London mission, and

also general superintendent of home missions (a new, undefined, role

which did not last). Back in Hull, he became Editor from 1857-62, and

in that year was President of Conference. In 1861 he produced the Primitive Methodist Revival Hymn Book,

'compiled from the large and small hymn books [of Bourne in 1825]', which went through various editions. He was a

keen total abstainer and supporter of the Band of Hope. Liberal in

politics, he was conservative in church polity.

For that year (1843) only, the minister was William Harland

(1801-80) - a Yorkshireman and a popular 'Ranter preacher' among the

seafarers and fishermen of the East coast where most of his 43-year

ministry was exercised, but whom (like others just-mentioned)

Conference sent to London, where he was Superintendent of the London mission, and

also general superintendent of home missions (a new, undefined, role

which did not last). Back in Hull, he became Editor from 1857-62, and

in that year was President of Conference. In 1861 he produced the Primitive Methodist Revival Hymn Book,

'compiled from the large and small hymn books [of Bourne in 1825]', which went through various editions. He was a

keen total abstainer and supporter of the Band of Hope. Liberal in

politics, he was conservative in church polity.  [John Flesher's edition

of the hymnbook - based on Bourne's work and other sources - was

produced at Sutton Street in 1865 under the publisher's name of William

Lister. A further version - which attempted a more thoroughgoing return

to Bourne's work - emerged in the late 1880s [left], edited by Dr George Booth JP of Chesterfield, and issued under the publisher's name of James

B. Knapp (previously a preacher in the

Leintwardine circuit in Herefordshire), who also published in the 1890s

(from 6 Sutton Street and 28 Paternoster Square) titles such as C.T.

Blomfield Not Rich, Yet a Gentleman

(an 'improving' romance), and various books for children, including Henry Woodcock Poor Charlie the Cripple; John Harvey Two

Boys; Henry Wood Smith Little Jim; Samuel Warren Farnford, or, School Life Tweny Years Ago; Wallace Gray A Child of the Hills; and Made for It; or, The Wild Flower Transplanted.] See this note and link on Methodist hymnals generally.

[John Flesher's edition

of the hymnbook - based on Bourne's work and other sources - was

produced at Sutton Street in 1865 under the publisher's name of William

Lister. A further version - which attempted a more thoroughgoing return

to Bourne's work - emerged in the late 1880s [left], edited by Dr George Booth JP of Chesterfield, and issued under the publisher's name of James

B. Knapp (previously a preacher in the

Leintwardine circuit in Herefordshire), who also published in the 1890s

(from 6 Sutton Street and 28 Paternoster Square) titles such as C.T.

Blomfield Not Rich, Yet a Gentleman

(an 'improving' romance), and various books for children, including Henry Woodcock Poor Charlie the Cripple; John Harvey Two

Boys; Henry Wood Smith Little Jim; Samuel Warren Farnford, or, School Life Tweny Years Ago; Wallace Gray A Child of the Hills; and Made for It; or, The Wild Flower Transplanted.] See this note and link on Methodist hymnals generally. The 1872 map [right] shows that the 'Prims' built a chapel on the site at 6 Sutton Street, just east of Christ Church Watney Street, whose vicar G.H.McGill's 1861 model census

says it seated 120, and estimated that the 'Ranters' Sunday School' had

100 attenders; however, the 1864 Primitive Methodist Magazine says it

seated 400, but was unsatisfactory because it was in a yard concealed

from view by dwelling houses. (McGill also lists another 'Primitive

Methodist' chapel in Watney Street, accommodating 50, but be probably

meant the New Connexion chapel described below.)

The 1872 map [right] shows that the 'Prims' built a chapel on the site at 6 Sutton Street, just east of Christ Church Watney Street, whose vicar G.H.McGill's 1861 model census

says it seated 120, and estimated that the 'Ranters' Sunday School' had

100 attenders; however, the 1864 Primitive Methodist Magazine says it

seated 400, but was unsatisfactory because it was in a yard concealed

from view by dwelling houses. (McGill also lists another 'Primitive

Methodist' chapel in Watney Street, accommodating 50, but be probably

meant the New Connexion chapel described below.)

In 1876 the forereunner of the Whitechapel Mission was launched, as the

'Working Lads' Institute and Home' (WLI), at the Mansion House, with

the Lord Mayor of London presiding and Henry Hill, a City banker, its

chief benefactor. It rented premises at The Mount on Whitechapel

Road until 1885 when a new building, at 285 Whitechapel Road, was

provided for

its work (hitting the headlines when it was used for one of the

'Ripper' enquiries). In 1896, when WLI was short of funds, Thomas Jackson

seized the opportunity and bought it, continuing the work of helping

young men into employment, and providing beds for the homeless - a 'Home for Friendless and Orphan Lads' - now in an

evangelistic context (the Mayor and Sheriff and others continued

to support the work, attending the annual anniversary events). Left, as both institute and mission hall, and post-1906 when worship had transferred to Brunswick Hall (see below).

In 1876 the forereunner of the Whitechapel Mission was launched, as the

'Working Lads' Institute and Home' (WLI), at the Mansion House, with

the Lord Mayor of London presiding and Henry Hill, a City banker, its

chief benefactor. It rented premises at The Mount on Whitechapel

Road until 1885 when a new building, at 285 Whitechapel Road, was

provided for

its work (hitting the headlines when it was used for one of the

'Ripper' enquiries). In 1896, when WLI was short of funds, Thomas Jackson

seized the opportunity and bought it, continuing the work of helping

young men into employment, and providing beds for the homeless - a 'Home for Friendless and Orphan Lads' - now in an

evangelistic context (the Mayor and Sheriff and others continued

to support the work, attending the annual anniversary events). Left, as both institute and mission hall, and post-1906 when worship had transferred to Brunswick Hall (see below).

Jackson [left

at various periods in his life, plus 1931 painting by Frank Beresford,

bought for the Memorial Room at WLI by his successor on behalf of Revd

W. & Mrs Potter] was one of the great figures of

Methodism in this period. Born in Belper in 1850 (where he attended a

Unitarian Sunday

School), he

served

in the East End for 56 years until his death in 1932 (the year of

Methodist re-union),

and also founded

missions in Walthamstow, Clapton and Southend. In 1901 he acquired

premises at Marine Parade, Southend, for convalescent and holiday

stays. In Whitechapel, the Mission provided free

breakfasts and penny dinners for local children, medical service,

free legal advice, a night shelter for homeless men, distribution of

food, coal and grocery tickets, and prison gate rescue work amongst

young lads, which developed into full probation work - Thompson being

recognised as a probation officer. On 18 October 1926, to mark his

jubilee in ministry, the Mansion House was opened for his supporters. He died in 1932. See further Brian Frost & Stuart Jordan Pioneers of Social Passion: London's Cosmopolitan Methodism (2006).

Jackson [left

at various periods in his life, plus 1931 painting by Frank Beresford,

bought for the Memorial Room at WLI by his successor on behalf of Revd

W. & Mrs Potter] was one of the great figures of

Methodism in this period. Born in Belper in 1850 (where he attended a

Unitarian Sunday

School), he

served

in the East End for 56 years until his death in 1932 (the year of

Methodist re-union),

and also founded

missions in Walthamstow, Clapton and Southend. In 1901 he acquired

premises at Marine Parade, Southend, for convalescent and holiday

stays. In Whitechapel, the Mission provided free

breakfasts and penny dinners for local children, medical service,

free legal advice, a night shelter for homeless men, distribution of

food, coal and grocery tickets, and prison gate rescue work amongst

young lads, which developed into full probation work - Thompson being

recognised as a probation officer. On 18 October 1926, to mark his

jubilee in ministry, the Mansion House was opened for his supporters. He died in 1932. See further Brian Frost & Stuart Jordan Pioneers of Social Passion: London's Cosmopolitan Methodism (2006).

In 1906 the Mission had acquired from the Congregationalists Brunswick Hall [two views right] - formerly Sion Chapel

- at 208-12 Whitechapel Road, which enabled the

separation of social and evangelistic work. It was licensed for

worship in 1907, and for weddings in 1911, and acquired an organ by Henry

Speechly of Dalston, formerly in the Primitive Methodist Chapel at The

Oval, Hackney Road. [Interior right, and House of Rest far right.]

In 1906 the Mission had acquired from the Congregationalists Brunswick Hall [two views right] - formerly Sion Chapel

- at 208-12 Whitechapel Road, which enabled the

separation of social and evangelistic work. It was licensed for

worship in 1907, and for weddings in 1911, and acquired an organ by Henry

Speechly of Dalston, formerly in the Primitive Methodist Chapel at The

Oval, Hackney Road. [Interior right, and House of Rest far right.]

Thomas Jackson's succcessor was James E. Thorp

(1919-46) [left - note

the wing collar of earlier years, which Jackson had also worn]. He was

from Sowerby Bridge (where he attended the

Primitive Methodist Sunday School) and had previously ministered in the

south west. He brought several of Jackson's ideas and projects to

fruition - he too was a recognised probation officer - including the

acquisition of Windyridge, at Thorrington

near Colchester, as a farm colony and hostel qualifying as

'conditional residence' for those serving probation orders. A group of

lads had camped in the grounds some years before, and Mrs Atterton, a

retired teacher, gave effect to her late husband's dying wish that

their house should be used for this purpose. Right are images of the 'group of lads' admitted in Whitechapel in the course of one year, and homeless men receiving rations. London Metropolitan Archives holds a rich resource of material from this period,

including accounts of night shelter users from 1926 and photos of

WLI activities in the 1930s. Here are many of of the annual reports of the Mission from those times to the present day.

Thomas Jackson's succcessor was James E. Thorp

(1919-46) [left - note

the wing collar of earlier years, which Jackson had also worn]. He was

from Sowerby Bridge (where he attended the

Primitive Methodist Sunday School) and had previously ministered in the

south west. He brought several of Jackson's ideas and projects to

fruition - he too was a recognised probation officer - including the

acquisition of Windyridge, at Thorrington

near Colchester, as a farm colony and hostel qualifying as

'conditional residence' for those serving probation orders. A group of

lads had camped in the grounds some years before, and Mrs Atterton, a

retired teacher, gave effect to her late husband's dying wish that

their house should be used for this purpose. Right are images of the 'group of lads' admitted in Whitechapel in the course of one year, and homeless men receiving rations. London Metropolitan Archives holds a rich resource of material from this period,

including accounts of night shelter users from 1926 and photos of

WLI activities in the 1930s. Here are many of of the annual reports of the Mission from those times to the present day.

After the war, Arthur Edward Doughty Clipson

[left] was the

superintendent minister from 1947, until his death in 1964. He had

previously served in the

Kidderminster, Pickering, Bolton and Bradford circuits. In 1948 the

Mission acquired a house in Tulse Hill, which they named

'Whitechapel House' - it was a probation hostel until 1956 when it

became a hostel for homeless lads. The WLI youth

centre and general office remained at

at 279 Commercial Road. Refurbished, it was re-opened in 1958 by the

Duke of Edinburgh. In Clipson's time there was manual work and classes

for social readjustment in the family. Eric Murray [right] was also a minister in the circuit at this time; in his latter years [far right] until 2011, living in Surbiton, he chaired the English Committee in aid of the Waldensian

Church Missions - Italian Protestants whose fascinating history long

predates the Reformation, and who have much in common with Methodism

(their guest house and centre in Rome is highly recommended!)

After the war, Arthur Edward Doughty Clipson

[left] was the

superintendent minister from 1947, until his death in 1964. He had

previously served in the

Kidderminster, Pickering, Bolton and Bradford circuits. In 1948 the

Mission acquired a house in Tulse Hill, which they named

'Whitechapel House' - it was a probation hostel until 1956 when it

became a hostel for homeless lads. The WLI youth

centre and general office remained at

at 279 Commercial Road. Refurbished, it was re-opened in 1958 by the

Duke of Edinburgh. In Clipson's time there was manual work and classes

for social readjustment in the family. Eric Murray [right] was also a minister in the circuit at this time; in his latter years [far right] until 2011, living in Surbiton, he chaired the English Committee in aid of the Waldensian

Church Missions - Italian Protestants whose fascinating history long

predates the Reformation, and who have much in common with Methodism

(their guest house and centre in Rome is highly recommended!)  The Superintendent of the Mission from 1964-70 was William Parkes

(1964-70) [first right]. Born in Dudley, he candidated for the ministry in Korea

while serving with the RAF and trained at Hartley Victoria College from

1953, serving in Barnsley and Sheffield. In 1963 he held a World

Methodist Council scholarship at the Candler School of Theology at

Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, studying 19th century

non-Wesleyan Methodist movements: an example of many published articles

is 'The Original Methodists: Primitive Methodist Reformers' [the so-called 'Selstonites'] in Proceedings of the Wesley Historical Society

vol XXXV (1965). A London PhD in criminology followed (and a paper 'Defences for Violence' in the New Law Journal for 1970). There were other historical and devotional works and

collections of sermons. He wa appointed a royal chaplain, and in his

later ministry (based in Essex) conducted preaching

tours, and camp meetings in the USA, until his death in 1999.

The Superintendent of the Mission from 1964-70 was William Parkes

(1964-70) [first right]. Born in Dudley, he candidated for the ministry in Korea

while serving with the RAF and trained at Hartley Victoria College from

1953, serving in Barnsley and Sheffield. In 1963 he held a World

Methodist Council scholarship at the Candler School of Theology at

Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, studying 19th century

non-Wesleyan Methodist movements: an example of many published articles

is 'The Original Methodists: Primitive Methodist Reformers' [the so-called 'Selstonites'] in Proceedings of the Wesley Historical Society

vol XXXV (1965). A London PhD in criminology followed (and a paper 'Defences for Violence' in the New Law Journal for 1970). There were other historical and devotional works and

collections of sermons. He wa appointed a royal chaplain, and in his

later ministry (based in Essex) conducted preaching

tours, and camp meetings in the USA, until his death in 1999.  John Jackson [right] was

Superintendent from 1970-74. He was a fourth-generation railwayman from

Winsford in Cheshire, working in signalling and telegraphy, and was

ordained in 1945 (studying at Richmond Theological College in Surrey - a Wesleyan college founded in 1843 which closed in 1972),

and had served in Stroud, Yorkshire, Stoke on Trent, Darlington, the

Victoria Hall Mission in Bolton and then as Superintendent of the

Albert Hall, Nottingham (also the city's main concert hall at the time)

where Sunday morning worship had been televised.

John Jackson [right] was

Superintendent from 1970-74. He was a fourth-generation railwayman from

Winsford in Cheshire, working in signalling and telegraphy, and was

ordained in 1945 (studying at Richmond Theological College in Surrey - a Wesleyan college founded in 1843 which closed in 1972),

and had served in Stroud, Yorkshire, Stoke on Trent, Darlington, the

Victoria Hall Mission in Bolton and then as Superintendent of the

Albert Hall, Nottingham (also the city's main concert hall at the time)

where Sunday morning worship had been televised.

Dr John Henry Chamberlayne was the minister until 1981 [ith his deaconess wife Mary - left]. He was originally a scholar of ancient Hebrew religion (Man in Society; The Old Testament Doctrine,

Epworth 1966), but became a lecturer on world religions and sociology

at Natal University in South Africa, and Atlanta University in the USA,

and a missionary teacher at Central China University. Back in England,

he was an Open University tutor, teaching the course 'The [originally Man's]

Religious Quest', with The Quest of Faith: an introduction to contemporary religions (REP 1969) as a source book; he was a member of the British Association for the Study [previously History] of Religions. His London doctorate on 'The People's Religion of China' was the basis of China and Its Religious Inheritance (Janus 1993). In 1996 (by then retired to Croydon) he provided the Horniman Museum

with 48 'Chinese objects'. He died in 2003.

Dr John Henry Chamberlayne was the minister until 1981 [ith his deaconess wife Mary - left]. He was originally a scholar of ancient Hebrew religion (Man in Society; The Old Testament Doctrine,

Epworth 1966), but became a lecturer on world religions and sociology

at Natal University in South Africa, and Atlanta University in the USA,

and a missionary teacher at Central China University. Back in England,

he was an Open University tutor, teaching the course 'The [originally Man's]

Religious Quest', with The Quest of Faith: an introduction to contemporary religions (REP 1969) as a source book; he was a member of the British Association for the Study [previously History] of Religions. His London doctorate on 'The People's Religion of China' was the basis of China and Its Religious Inheritance (Janus 1993). In 1996 (by then retired to Croydon) he provided the Horniman Museum

with 48 'Chinese objects'. He died in 2003.

His successor was also a minister with scholarly and practical interfaith experience. Peter Jennings (b.1937) [right, and with his wife Cynthia] was a pupil of Manchester Grammar School and after Oxford trained for ministry at Hartley Victoria College

in Manchester where his

interest in the Hebrew scriptures led to an MA in Semitic Studies.

After a probationary ministry in Swansea, he was ordained in 1965 and

became tutor and warden of the Social Studies Centre of the London Circuit (East) of the

Methodist Conference, involved in youth work in

an ethnically diverse community in north London. He then became General Secretary of the Council for Christians and Jews (founded 1942 by Chief Rabbi Joseph H. Hertz and Archbishop William Temple). A 1976 profile in the Jewish Observer and Middle East Review said without being disrespectful, the best way to

describe the delightful Rev. Peter Jennings, general secretary of the

Council of Christians and Jews, is 'an irreverent reverend'; his language is colourful.... He came to Whitechapel in 1981 as Director of the Mission, but continued his CCJ involvement, as chair of the standing conference of local councils, and remained involved with the British Friends of Nes Ammim, a pioneering Christian community in Israel. See further Marcus Braybrooke Children of One God: a history of the Council of Christians and Jews ( Valentine Mitchell 1991). In Jennings' time here, as Muslims replaced Jews on the local scene, he said we should stop calling Muslims

'people of another faith' and start calling them 'other faithful people'. He left in 1990 to become a superintendent minister in Ilford.

His successor was also a minister with scholarly and practical interfaith experience. Peter Jennings (b.1937) [right, and with his wife Cynthia] was a pupil of Manchester Grammar School and after Oxford trained for ministry at Hartley Victoria College

in Manchester where his

interest in the Hebrew scriptures led to an MA in Semitic Studies.

After a probationary ministry in Swansea, he was ordained in 1965 and

became tutor and warden of the Social Studies Centre of the London Circuit (East) of the

Methodist Conference, involved in youth work in

an ethnically diverse community in north London. He then became General Secretary of the Council for Christians and Jews (founded 1942 by Chief Rabbi Joseph H. Hertz and Archbishop William Temple). A 1976 profile in the Jewish Observer and Middle East Review said without being disrespectful, the best way to

describe the delightful Rev. Peter Jennings, general secretary of the

Council of Christians and Jews, is 'an irreverent reverend'; his language is colourful.... He came to Whitechapel in 1981 as Director of the Mission, but continued his CCJ involvement, as chair of the standing conference of local councils, and remained involved with the British Friends of Nes Ammim, a pioneering Christian community in Israel. See further Marcus Braybrooke Children of One God: a history of the Council of Christians and Jews ( Valentine Mitchell 1991). In Jennings' time here, as Muslims replaced Jews on the local scene, he said we should stop calling Muslims

'people of another faith' and start calling them 'other faithful people'. He left in 1990 to become a superintendent minister in Ilford.

His successor at the Mission was John Lines MBE (1990-95) [first left]. John was a Metropolitan Police motorcyclist before ordination, and his hobby the preservation of old buses (see p11 of this link); he is now honorary vice-president of London Stedfast Association, for former members and supporters of the Boys' Brigade. Richard Chapple (1995-99) [second left] came as Superintendent from Bexhill-on-Sea and went on to Colchester. David Hill succeeded him as superintendent of the Tower Hamlets circuit. Tony Miller

MBE [right] was the first lay Director of the Mission: he was a volunteer in 1981, became daycare

manager in 1988, and undertook overall responsibility in 1995. During these years the centres at Southend, Windyridge and Tulse Hill

closed, and the Mission gradually returned all its operations to

Whitechapel. Brunswick Hall at 208-12 (Maples Place) was

demolished in 1969 and rebuilt; it still operates as a day centre

(and our parish supports it with Harvest gifts each year).

His successor at the Mission was John Lines MBE (1990-95) [first left]. John was a Metropolitan Police motorcyclist before ordination, and his hobby the preservation of old buses (see p11 of this link); he is now honorary vice-president of London Stedfast Association, for former members and supporters of the Boys' Brigade. Richard Chapple (1995-99) [second left] came as Superintendent from Bexhill-on-Sea and went on to Colchester. David Hill succeeded him as superintendent of the Tower Hamlets circuit. Tony Miller

MBE [right] was the first lay Director of the Mission: he was a volunteer in 1981, became daycare

manager in 1988, and undertook overall responsibility in 1995. During these years the centres at Southend, Windyridge and Tulse Hill

closed, and the Mission gradually returned all its operations to

Whitechapel. Brunswick Hall at 208-12 (Maples Place) was

demolished in 1969 and rebuilt; it still operates as a day centre

(and our parish supports it with Harvest gifts each year).Methodist New Connexion, Bethesda Chapel, Watney Street

The

New

Connexion was the first of the Methodist splits, led initially by

Alexander Kilham

(1762-98) [right], a minister in Sheffield, not on any doctrinal issues but over the rights and

representation of lay people in

church governance. It was a democratic movement, giving an equal voice

to ministers and elected laity - for which the 'Kilhamites' were

denounced as revolutionary sympathisers of Tom Paine. A 1795 'Plan of

Pacification' failed to resolve the issue, and they broke away in 1797,

founding their own chapels throughout the next century.

The

New

Connexion was the first of the Methodist splits, led initially by

Alexander Kilham

(1762-98) [right], a minister in Sheffield, not on any doctrinal issues but over the rights and

representation of lay people in

church governance. It was a democratic movement, giving an equal voice

to ministers and elected laity - for which the 'Kilhamites' were

denounced as revolutionary sympathisers of Tom Paine. A 1795 'Plan of

Pacification' failed to resolve the issue, and they broke away in 1797,

founding their own chapels throughout the next century. | Sunday, March 19th, 1854. Left home at 10 o'clock for Watney Street; felt much sympathy for the poor neglected inhabitants of Wapping, and its neighbourhood, as I walked down the filthy streets and beheld the wretchedness and wickedness of its people. Reached Bethesda Chapel, and found a nice little congregation, who seemed to hear the word of the Lord gladly. At night a good congregation. Felt much power in preaching. The people wept and listened with much avidity. Commenced or rather, continued the meeting by holding a prayer-meeting. All, or nearly all, stayed. Gave an invitation to those who were decided to serve the Lord to come forward and many came fifteen in all of whom fourteen professed to find Jesus, and went home happy in His love. Many of these were very interesting cases. All engaged were much blessed. Tired and weary, I reached home soon after 11 o'clock. |

| At Watney Street I held a week's special services, preaching every night. Very many gave their hearts to God. I never knew a work more apparently satisfactory in proportion to its extent. Some most precious cases I have beheld, and I thank God for them. The people appear very happy and united. God bless and keep them! |

| We

had indeed a glorious day yesterday. Good congregation in the morning.

In the afternoon we held a love-feast. Seventeen spoke, and nearly all

praised God for the day I came

among them. Many of my spiritual children, with streaming eyes and

overflowing hearts, told us how God, for Christ's sake, had made them

happy. At night, notwithstanding the unfavourable weather, we had the

place crammed every nook and corner, and in the prayer-meeting we had

near twenty penitents. Mr. Atkinson's daughter and Mr. Gould, her

intended husband, came forward and with many tears and prayers sought

and found mercy. Two black women came, and altogether it was a good

night.

|

In 1847 the New Connexion appealed for £20,000 to build a college, but only a third of this sum was raised. In 1864 the Sheffield

steel tycoon Mark Firth financed Ranmoor College

(he and his brothers played a key role in the development of this

affluent western suburb). It opened with 16 students [right]

and closed in 1919

when Victoria Park College, in Manchester [following paragraph], became the base for all the United

Methodists (staff having commuted across the Pennines for a time). The

building became a nurses' hostel for the Royal Hospital until 1940,

then an Air Raid headquarters, then for 16 years a men's hall of

residence for Sheffield University; it was demolished in 1965.

In 1847 the New Connexion appealed for £20,000 to build a college, but only a third of this sum was raised. In 1864 the Sheffield

steel tycoon Mark Firth financed Ranmoor College

(he and his brothers played a key role in the development of this

affluent western suburb). It opened with 16 students [right]

and closed in 1919

when Victoria Park College, in Manchester [following paragraph], became the base for all the United

Methodists (staff having commuted across the Pennines for a time). The

building became a nurses' hostel for the Royal Hospital until 1940,

then an Air Raid headquarters, then for 16 years a men's hall of

residence for Sheffield University; it was demolished in 1965. The United

Methodist Free Church college was built in 1871 in Victoria Park, Manchester. From the 1980s the

Bible Christians had tailor-made courses at Shebbear for their

ministers, but they moved to this site after the 1907 union that created the United Methodist Church - the New Connexion, as noted above, joining them a few years later. Student group [left] in 1926.

The United

Methodist Free Church college was built in 1871 in Victoria Park, Manchester. From the 1980s the

Bible Christians had tailor-made courses at Shebbear for their

ministers, but they moved to this site after the 1907 union that created the United Methodist Church - the New Connexion, as noted above, joining them a few years later. Student group [left] in 1926.

Primitive Methodist

training began in 1863 at Elmfield House, near York, moving to the

Sunderland Theological Institute in 1868, and to Manchester in 1881, to

link with the new Victoria University of Manchester (formerly, from

1851, Owen's College). Here in 1878 a grand college was built in

Alexandra Road

South, and extended from 1893-98 (see this description of the early years) and subsequently; in 1906 it was named Hartley College

after Sir William P. Hartley (of jam fame). Its most famous tutor (from

1892-1929) was Arthur Samuel Peake, author of the famous one-volume

bible commentary, first Rylands Professor of Biblical Criticism in

Manchester University and a Pro Vice-Chancellor. In 1934, after

Methodist reunification, it became Hartley Victoria College when nearby Victoria Park College (above) joined it [college chapel window right]. In

1973, when training moved to the new Luther King House, it became a

hall of residence for the Royal Manchester (later Royal Northern)

College of Music, and in 2001 Kassim Darwish Grammar School for

Boys, an independent Muslim school.

Primitive Methodist

training began in 1863 at Elmfield House, near York, moving to the

Sunderland Theological Institute in 1868, and to Manchester in 1881, to

link with the new Victoria University of Manchester (formerly, from

1851, Owen's College). Here in 1878 a grand college was built in

Alexandra Road

South, and extended from 1893-98 (see this description of the early years) and subsequently; in 1906 it was named Hartley College

after Sir William P. Hartley (of jam fame). Its most famous tutor (from

1892-1929) was Arthur Samuel Peake, author of the famous one-volume

bible commentary, first Rylands Professor of Biblical Criticism in

Manchester University and a Pro Vice-Chancellor. In 1934, after

Methodist reunification, it became Hartley Victoria College when nearby Victoria Park College (above) joined it [college chapel window right]. In

1973, when training moved to the new Luther King House, it became a

hall of residence for the Royal Manchester (later Royal Northern)

College of Music, and in 2001 Kassim Darwish Grammar School for

Boys, an independent Muslim school.

Luther King House, in Brighton Grove, was built on the site of the former Baptist College [left], and began as a union with the Northern Baptist College, to which was added Northern College (United Reformed Church, Congregationalists and Moravians) and the small Unitarian college, plus links with the mainly-Anglican (non-residential) Northern Ordination Course to form a Federation, which in 1998 became the Partnership for Theological Education,

in recognition both of its wider links and emphasis on training for the

whole church, not just clergy. The site is marketed as a functions

venue, and is licensed for civil marriages [chapel right, and courtyard].

Luther King House, in Brighton Grove, was built on the site of the former Baptist College [left], and began as a union with the Northern Baptist College, to which was added Northern College (United Reformed Church, Congregationalists and Moravians) and the small Unitarian college, plus links with the mainly-Anglican (non-residential) Northern Ordination Course to form a Federation, which in 1998 became the Partnership for Theological Education,

in recognition both of its wider links and emphasis on training for the

whole church, not just clergy. The site is marketed as a functions

venue, and is licensed for civil marriages [chapel right, and courtyard].THE COUNTESS OF HUNTINGDON'S CONNEXION

The Countess

of Huntingdon’s

Connexion was (and is, for a few

chapels remain, mostly

in the south-east) a group of Calvinistic Methodist churches, under the

personal direction of Selina,

Countess of Huntingdon until her death in

1791. She liked to move ‘her’ ministers around on a

regular

basis! They trained at Trevecca in Wales, and then, after her death when the decision was made to move to a convenient place near London, at Cheshunt [right]; the trust deed

for the college makes interesting reading, and has some links with the

family of Dr Herbert Mayo, Rector of St George-in-the-East. When the

Connexion's training transferred to Cambridge, the site became an Anglican theological college, sponsored by the four local dioceses of London, St Albans, Southwark and Chelmsford, from 1909 until its closure in 1969.

The Countess

of Huntingdon’s

Connexion was (and is, for a few

chapels remain, mostly

in the south-east) a group of Calvinistic Methodist churches, under the

personal direction of Selina,

Countess of Huntingdon until her death in

1791. She liked to move ‘her’ ministers around on a

regular

basis! They trained at Trevecca in Wales, and then, after her death when the decision was made to move to a convenient place near London, at Cheshunt [right]; the trust deed

for the college makes interesting reading, and has some links with the

family of Dr Herbert Mayo, Rector of St George-in-the-East. When the

Connexion's training transferred to Cambridge, the site became an Anglican theological college, sponsored by the four local dioceses of London, St Albans, Southwark and Chelmsford, from 1909 until its closure in 1969.

From 1773, the Countess' ministers preached under the mulberry trees in Wapping, and in that year she reported that I am treating about ground to build a large, very large chapel at Wapping; in 1776 Mulberry Gardens Chapel was opened. The reason for the delay relates to disagreement about the choice of minister; this, and the subsequent history of the building, are explained more fully in this biography of the Countess. It was fitted up in a tasteful manner and opened using Anglican rites. Allegedly the hymn-singing was so hearty that Dr Mayo, in his nearby meeting-house, could not be heard when preaching.

One of her ministers, appointed in 1778, was a Cornishman John Eyre, an able and well-respected preacher, who was ordained into the Anglican church the following year (not all that strange, since the Connexion did not regard itself as formally separated from the established church, and used its liturgy). He went on to serve in Chelsea and Homerton. However, he kept contact with former friends, and was a keen supporter of the London Missionary Society. Two others whom she did not appoint - despite local pressure - were William Simpson, despite his significant financial contributions to the chapel, and William Aldrige, who left the Connexion and became a Calvinistic Methodist, though remained on good terms with the Countess - he also subscribed to Olaudah Equiano's Interesting Narrative.

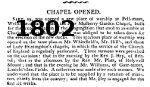

T. & R. Allen's

Brewery declined to renew the lease on this chapel when it

expired (instead it was offered to Pell Street Meeting), and the

congregation dispersed - some to the Countess' original chapel at Spa

Fields,

some to Sion Chapel, but most to Charlotte Street. When this

latter building in turn was demolished to make way for the Docks, she

built 'New Mulberry Garden Chapel' in Pell Street, with its

main entrance in Prince's Square, in 1802 (see opening notice right from the Evangelical Magazine vol.10). It was a simple

building – a plain brick box, without even a bell-cote, and had high

pews and a gallery. There

was

a vault below, and two further ones under the school and almshouses,

which became very full and insanitary. (In his will John Luden, slopseller

of 14 Upper East Smithfield, who died in 1845, had specified burial in

this vault for his son Joseph, and for himself, but it is doubtful

whether this was achieved given subsequent developments.)

T. & R. Allen's

Brewery declined to renew the lease on this chapel when it

expired (instead it was offered to Pell Street Meeting), and the

congregation dispersed - some to the Countess' original chapel at Spa

Fields,

some to Sion Chapel, but most to Charlotte Street. When this

latter building in turn was demolished to make way for the Docks, she

built 'New Mulberry Garden Chapel' in Pell Street, with its

main entrance in Prince's Square, in 1802 (see opening notice right from the Evangelical Magazine vol.10). It was a simple

building – a plain brick box, without even a bell-cote, and had high

pews and a gallery. There

was

a vault below, and two further ones under the school and almshouses,

which became very full and insanitary. (In his will John Luden, slopseller

of 14 Upper East Smithfield, who died in 1845, had specified burial in

this vault for his son Joseph, and for himself, but it is doubtful

whether this was achieved given subsequent developments.)

As

explained above, the

Anglican liturgy was used in the chapel, whose minister from 1804-07 was the Rev Isaac Nicholson.

He was born in Netherwasdale, Cumbria in 1761, was an ordained Anglican minister, and had been President of

the college at Cheshunt following the death of Lady Huntingdon; he published a Collection of Hymns....for

Mulberry Gardens Chapel in 1807. He was a noted preacher, and

gave lectures every

Tuesday evening. Among his published sermons, delivered at Pell Street, were The Office and Operations of the Spirit of God as a Witness, intended as an antidote against the virulent poison of the Sandemanian heresy, diffused in London by the Hibernian stranger (1806). He was also an opponent of promiscuous and unscriptural communion, and

instigated a system of moral examination by church leaders for

admission to the sacrament. After his death in 1807 (aged 47) this and

other aspects of

his church governance were subject to legal challenge in the High Court

of Chancery. While this was being resolved, some of the congregation

transferred for a time to the Pell Street Independent Meeting, which in

1805 had taken over a former mariner's chapel twelve yards away.

Nicholson's successor, whom he first met while convalescing from 'nervous debility' in Cumbria and brought back to London, was the Rev Robert Stodhart, for more details of whom see here. He remained until 1842 (living in Islington), and died died in 1846, aged 67. They chapel continued to use the Anglican liturgy; by this time, however, church order was similar to that of the Congregationalists. In his time the chapel became an 'auxiliary society' of the London Missionary Society, founded in 1795 by evangelical Anglicans and nonconformists - and which became the main missionary agency of the Congregationalists.

When

the Independent chapel in Pell Street closed around 1833, Stodhart

bought the premises at auction to prevent it falling into inappropriate

hands. The

Connexion abandoned Mulberry Gardens Chapel in the 1840s (the last

recorded baptisms were in 1837 - and see here for the visit of the black evangelist Zilpha Elaw in 1845), but there was one more minister: when

Stodhart resigned in 1842, Joseph

Cartwright

took his place. He was an Independent who had been offered a Church of

England title but declined; had served in Orpington and Devonport; and

had supplied at New Mulberry Gardens Chapel for several weeks before

receiving their call. The Monthly Repository's portrait gives a glimpse

of which doctrines mattered, and the language in which they were

expressed:

His ministry here was short-lived. The chapel stood empty for a time, before the parish church acquired it and it became St Matthew Pell Street. Among those who ministered here in the late 1850s was Thomas Tenison Cuffe, who having seceded from the Church of England in 1850 to join the Countess' Connexion apparently returned to the Church of England a few years later.

In

2004 Sotheby's sold a picture [left] by Anthony Stewart (1773-1846) of A

Child, said to be the Baroness Emilia Kayne von Gorgan Schillitz,

wearing a low-cut white dress with frilled trim, her right arm raised,

holding her coral necklace, parkland background, in a gilt-mounted papier-mâché frame. In

the reverse of this miniature was a card from Mulberry Gardens Chapel

(why is not clear) with the words 'A. Stewart, Portrait & Miniature

Painter, 17 Prince's Square, St. George's East' and his trade label.

In

2004 Sotheby's sold a picture [left] by Anthony Stewart (1773-1846) of A

Child, said to be the Baroness Emilia Kayne von Gorgan Schillitz,

wearing a low-cut white dress with frilled trim, her right arm raised,

holding her coral necklace, parkland background, in a gilt-mounted papier-mâché frame. In

the reverse of this miniature was a card from Mulberry Gardens Chapel

(why is not clear) with the words 'A. Stewart, Portrait & Miniature

Painter, 17 Prince's Square, St. George's East' and his trade label. In

1790 - the year before the death of the Countess - the Connexion took

on a former theatre on Whitechapel Road, which was fitted out as Zion

Chapel. The dressing rooms were turned into vestries, and a pulpit

built on the front of the stage. It was fairly spacious: the pit was

filled with seats, and the galleries were large and accommodating.

When Pell Street failed, efforts were made to revive the

Connexion's cause locally. went into decline on the death of the

Countess, despite various attempts to revive the cause: its minister in the 1840s was James Sherman, 1796-1862, trained at Cheshunt College. In

1846 Bosun Smith attended a Tea Meeting, and wrote of his hopes that

since Pell Street was a complete failure, there should be one settled

minister, and occasional supplies from the country to make it popular,

and a great evangelical working manufactory, to qualify laborers male

and female, for the immense mass of wretchedenss, filth, and misery,

drunkeneness, debauchery and crime, in the vicinity of Zion Chapel.

This is all the more necessary, because in the main street of

Whitechapel, and at no very great distance, is a Hall of Science,

filled with crowds of the working classes to infidel lectures night

after night.

In