A priest and poet at St George-in-the-East

A priest and poet at St George-in-the-East

reflections courtesy of Leo Aylen

Father

Alex Solomon was a remarkable priest - not only a very holy man, but

also a sensitive interpreter of Chopin, originally trained by the

Jesuits to be a professional recitalist. Although an Indian, born and

raised under Kanchenjunga, he fitted very well into the tradition of

East End Anglo-Catholic priests like John Groser, though he was not a

campaigning Christian Socialist as John Groser had been. 'Father

Solly', as he was known in the district, appeared to do very little,

but he was always around, available, in the beautiful St George’s

church, suffusing an atmosphere of active peace. Of course the beauty

of the church contributed to this. But his active peace was just as

energetic before Arthur Bailey had achieved his restoration of the

Hawksmoor building, when the ‘church’ was the dark green upper room of

a dingy church hall,.

Active peace. People came in contact with Father Solly, and started to

do things. Andrew Quicke and his fellow Marlburian Richard Ford

arrived somehow or other, and somehow or other found themselves running

youth clubs, while living in the top flat of the Rectory. Andrew

brought in Leo Aylen, who was writing and directing plays in Bristol,

and who stayed in that flat when he came to London. Leo’s first

assignment, whenever he was at St George’s, was to play the piano for

services in the upper-room temporary church. Although that ‘church’ was

hardly an architectural triumph, Father Solly made sure the piano was

excellent and very suitable for the Bach preludes and fugues which have

always been Leo’s passion. Similarly, when the Hawksmoor building was

restored, Douglas Mews, the organist of St George’s Cathedral,

Southwark, designed a small but very effective organ, excellently

placed so that the organist heard exactly the same sound as the

congregation heard. Again Leo took great delight in playing it for

services, and once again exulted in its excellent rendering of his

beloved Bach’s organ works.

Father Solly’s active peace was already working on Leo. While the

Hawksmoor shell was still a shell full of building-site debris, somehow

the conversation between priest and poet had reached a point when a

decision seemed to have been taken that Leo would write a St George

play to celebrate the opening of the restoration. Well, as the

technicians say, “Impossible — we do immediately; miracles take a bit

longer". To put the play on actually at the opening proved crazily

over-ambitious. Leo had written a Christmas play called The Adoration of the Magi,

which had been performed in Oxford with a cast half of student actors,

half of local youth. This was produced in St George’s the Christmas

after the restoration. Leo had by that time come to London, was working

for BBC Education, producing and directing poetry and drama for

teenagers, and had joined Andrew and Richard in the flat at the top of

the rectory. Leo collected a cast of seven professionals, and called in

local young people from the youth club for the walk-on parts. The play

went well, so now the challenge was to write and produce George. Three

professional actors, Timothy West, David King, and David Spenser, were

cast. Many years later, Tim West is a household name with an extremely

distinguished career behind him. But at the time of George, it was

David King who was the star, because he was playing a doctor in a TV

soap opera. David was a good singer (possibly an ex-King’s choral

scholar?), and when the cast went into the local pubs, David was always

asked to sing. He had, however, also done Russian while on National

Service, and when asked to sing, he’d choose to sing a Russian song.

“If I do that,” he said, “they don’t ask me to sing another one", and

laughed.

Walk-on parts were found for some local teenagers. But the amateur

choruses demanded more talent than the local youth possessed. Toynbee

Hall ran many adult education courses for East End youth. Somehow or

other Leo was invited by Toynbee Hall to ‘teach’ a drama course, on the

understanding that this course would simply consist of rehearsing the

choruses of George. As one might expect, the pagan chorus members were

required to be more violent than the Christians. One of these Toynbee

Hall East Enders, Henry Goodman, emerged as obviously the most powerful

performer, and was made the leader of the pagans. He went on to act

professionally, first in South Africa, and then back in England. He has

now played many West End leads, and has a name almost as respected as

Tim West’s.

Rehearsals threw up East End problems. Cannon Street Road, in which St

George’s stands, was a seriously dangerous street at night. Opposite

the church was a fruit stall which, surprisingly, stayed open into the

small hours, needless to say selling not fruit, but ladies of the

night. After midnight, the police left the prostitutes to their

business without restraints. It would have been dangerous for the

Toynbee Hall teenagers to walk back to Toynbee Hall after rehearsal.

Leo drove them in his Morris Minor convertible. One night he was

driving as usual with the fourteen Stepney teenagers in the open car. A

police car passed. One of the kids shouted out laughing “It’s the law,

it’s the law". That provoked 'the law' into taking notice. Leo was

charged, and brought before the magistrates. Sadly, after being charged

for driving the fourteen teenagers through the violent Stepney streets,

Leo felt continuing to drive them would be inadvisable. The very next

night one of the girls was attacked, and hit on the head with an iron

bar. Leo took her to the nearest hospital, and spent most of the night

sitting in casualty waiting for her to be treated. When he was tried by

the magistrate, he attempted to defend himself, saying that if he was

not allowed to drive the teenagers back to base, they would be attacked

with iron bars. The magistrate hardly listened, and fined Leo what was

then a considerable fine.

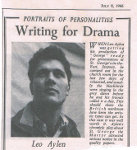

Somehow or other the play came together. It was complicated

technically. Leo had a brilliant lighting-designer cum

lighting-cameraman friend, Dick Brett, who did the stage lighting.

Another BBC employee, John Harris, at that time only a projectionist,

but later to become a producer, stage-managed. The night before the

opening, there was still much to be done. Leo and John worked until the

small hours, and then slept on the floor of the church. The Church

Times did a profile piece on Leo, and sleeping on the St George’s floor

provided good introductory copy.

Somehow or other the play came together. It was complicated

technically. Leo had a brilliant lighting-designer cum

lighting-cameraman friend, Dick Brett, who did the stage lighting.

Another BBC employee, John Harris, at that time only a projectionist,

but later to become a producer, stage-managed. The night before the

opening, there was still much to be done. Leo and John worked until the

small hours, and then slept on the floor of the church. The Church

Times did a profile piece on Leo, and sleeping on the St George’s floor

provided good introductory copy.

The play was reviewed by The Guardian as follows:

| GEORGE at St George’s-in-the-East by Terry Coleman NICHOLAS HAWKSMOOR was, as is well known, a celebrated architect of those theatres we call churches. St George’s-in-the-East was built by 1729, blitzed in 1941, restored by 1964. The splendid shell is still Hawksmoor’s, the interior is in the best design-centre style, and it was here, before the altar last night, that Mr Leo Aylen’s play George was performed before an audience that was unsure whether or not to consider itself a congregation. Some chatted, others crossed themselves and nodded towards the altar now and again. After a supporting programme of prayer, psalm, lessons and hymn, after the priest had asked the Lord to be with the people, and they had replied, in effect “You, too” — after that, the play proper. Diocletian is busy, first tolerating, then persecuting fourth-century Christianity. A young soldier called George insults the emperor by tearing down a ban-the-Christians edict, is martyred and becomes St George. But eventually, as we are told at the end, Christianity was adopted and became the official religion of the civilised world. It was all very well presented. Mr Aylen, who also directed, is especially good with light and sound, with flames licking and with bells. Three actors — David King, Timothy West, and David Spenser — sustained the main parts, and the young people of the parish, as Christian and pagan choruses, moved well, mostly in bare feet on the wooden floor of the aisle and the carpet before the altar. At the end, when the players had left, men and women of the church in everyday clothes proceeded up the aisle to lay crosses before the altar. When two or three are gathered together, as you might say, they shall make a play. And after last night no one can say that the devil has all the good theatres. |

Leo

returned to St George’s from time to time. After Father Solly had

retired, Bishop Jim Thompson announced his intention to close down St

George’s and build what he called a ‘Worship Centre’ two miles away.

The parish was horrified. Leo was called to join the protest to save St

George’s. What Bishop Jim had not realised was the number of

professional artists who had been drawn by Father Solly’s active peace

to use the church or church hall. The guitarist John Williams had

played there, the Royal Shakespeare Company had rehearsed there, and

there were many others. The protest took Bishop Jim by surprise. A

working party was formed to consider whether St George’s could become a

Christian Arts Centre. Leo was invited on to the working party along

with James Roose Evans, theatre director and non-stipendiary priest.

Exciting proposals were made, but lack of funds meant the project

disappeared into the mist. At least, however, St George’s was

reprieved, and the ‘Worship Centre’ never built.

The East End made a deep impression on Leo. He has made a number of

films for BBC (and ITV), and was nominated for a BAFTA award. One of

his films, called Who’ll Buy A Bubble?

was about the dehumanising effect of the East End tower blocks. Leo

discovered a group of local people who met regularly to create

improvised drama. He took them out into the neighbourhood, and filmed

them while they improvised — in a market, in or under the tower blocks,

on derelict waste-land, or joining in with mentally disabled people,

and with passers-by they met on the streets. A butcher, one of the

participants, described the people obliged to live in the cramped

flats high in the tower blocks: “they sort of move around from corner

to corner.” A trailer sequence from Who’ll Buy A Bubble? can be seen here on YouTube or on the film page of Leo Aylen’s website.

A pleasant 2013 postscript:

Father Solly, while still the Rector, told Leo on a return visit to St

George’s about a tramp who came regularly into the church, sat down and

played the grand piano. After about an hour, he would get up and leave,

never entering into any conversation. Leo wrote a poem, reproducing

Father Solly’s account of what happened. This was published in Leo’s

sixth collection Jumping Shoes (1983), and then again in his Selected Poems, Dancing the Impossible (1997). Leo’s ninth collection The Day The Grass Came (2012) received favourable reviews from Melvyn Bragg, Simon Callow, and others (including the Church Times),

and he has been performing in various festivals. Timothy West’s wife,

Prunella Scales, read 'The Day The Grass Came' and wrote

enthusiastically about it to Leo. This has led to Leo and Prunella

doing a two-man show of Leo’s poetry: in the Frome Festival July 14th,

2013, in Salisbury Playhouse, September 23rd, 2013, and in the Bristol

Festival October 5th, 2013. The St George’s tramp poem is included in

the programme.

|

The piano-playing tramp

An East End priest describes one of his regular visitors He appears like a drowned man’s ghost, Dripping the seaweed of bombsite and meths-bottle, With the East End clinging to his scalp like lice, To sit in our golden church of glass and mosaic, Letting the light trickle through his fingers Down on the keyboard of piano or organ Till it liquefies into old-time music. Our graveyard’s Victorian salon-balladeers Poke their skulls round their tombstones to listen. One hour later, the music ceases. He shuts the keyboard lid, Slides back into the pondweed of his anonymity. The gap of black water that he opened Closes behind him … |

June 2013

Back to Crypt Hall | Back to Church & Rectory residents