Peabody (Whitechapel) Estate, Glasshouse Street

Peabody (Whitechapel) Estate, Glasshouse Street

(now John Fisher

Street) see also Katharine Buildings

The major developers at this period - others arose later - were the Four Per Cent Industrial Dwellings Company [founded by Lord Rothschild and other Jewish philanthropists, with mainly Jewish tenants - see here - and renamed the 'Industrial Dwellings Society (1885) Ltd'], the

Improved Industrial Dwellings Company (whose chairman was Sir Sydney Waterlow - see Harry Jones' 1875 comments here), the Artizans', Labourers

& General Dwellings Company (who initially concentrated on low-rise

suburban development rather than blocks of flats), and the

philanthropic Peabody Trust, who probably made the largest impact by

the scale of their developments (which made the '5%' principle more

achievable), and set decent, if not exemplary, standards for others.

Because

of the difficulties of the Whitechapel site (bisected by a curved

viaduct leading to a Great Eastern Railway depot, and hard up against

the Royal Mint) it was the Peabody Trust that was to develop most of it.

The major developers at this period - others arose later - were the Four Per Cent Industrial Dwellings Company [founded by Lord Rothschild and other Jewish philanthropists, with mainly Jewish tenants - see here - and renamed the 'Industrial Dwellings Society (1885) Ltd'], the

Improved Industrial Dwellings Company (whose chairman was Sir Sydney Waterlow - see Harry Jones' 1875 comments here), the Artizans', Labourers

& General Dwellings Company (who initially concentrated on low-rise

suburban development rather than blocks of flats), and the

philanthropic Peabody Trust, who probably made the largest impact by

the scale of their developments (which made the '5%' principle more

achievable), and set decent, if not exemplary, standards for others.

Because

of the difficulties of the Whitechapel site (bisected by a curved

viaduct leading to a Great Eastern Railway depot, and hard up against

the Royal Mint) it was the Peabody Trust that was to develop most of it. George

Peabody (1795-1869) [picture

1857 by James Reid Lambdin] was a New

Englander who made a fortune during the rapid growth of Baltimore as a

port and trade centre, and moved to London in 1837, aged 42, to

consolidate his empire (financing American railroad expansion and the

first transatlantic cables, and establishing the merchant bank that was

to become Morgan Grenfell). He financed the American exhibits at the

1851 Great Exhibition. Ironically, for one who aged 17 had volunteered

as a soldier to fight against the advancing British fleet, he did much

to foster Anglo-American trade and political relationships; and come

the Civil War (which divided the American community in London) pressed

for educational opportunities for blacks. His major benefaction was the

£150,000 Peabody Donation Fund (the Peabody Trust), later increased to

£500,000, for the

construction of such improved dwellings for the poor as may combine in

the utmost possible degree the essentials of healthfulness, comfort,

social enjoyment and economy for Londoners, a gift acknowledged

by

Queen Victoria as wholly without

parallel. Its creation was marked by

a statue in Threadneedle Street unveiled by the Prince of Wales. When

he died in 1869, the carriages of the Queen and the Prince of Wales

followed the hearse to Westminster Abbey, where Gladstone was among the

mourners. He was the first American to be awarded the Freedom of the

City of London. George

Peabody (1795-1869) [picture

1857 by James Reid Lambdin] was a New

Englander who made a fortune during the rapid growth of Baltimore as a

port and trade centre, and moved to London in 1837, aged 42, to

consolidate his empire (financing American railroad expansion and the

first transatlantic cables, and establishing the merchant bank that was

to become Morgan Grenfell). He financed the American exhibits at the

1851 Great Exhibition. Ironically, for one who aged 17 had volunteered

as a soldier to fight against the advancing British fleet, he did much

to foster Anglo-American trade and political relationships; and come

the Civil War (which divided the American community in London) pressed

for educational opportunities for blacks. His major benefaction was the

£150,000 Peabody Donation Fund (the Peabody Trust), later increased to

£500,000, for the

construction of such improved dwellings for the poor as may combine in

the utmost possible degree the essentials of healthfulness, comfort,

social enjoyment and economy for Londoners, a gift acknowledged

by

Queen Victoria as wholly without

parallel. Its creation was marked by

a statue in Threadneedle Street unveiled by the Prince of Wales. When

he died in 1869, the carriages of the Queen and the Prince of Wales

followed the hearse to Westminster Abbey, where Gladstone was among the

mourners. He was the first American to be awarded the Freedom of the

City of London. |

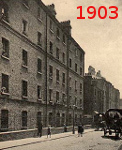

In 1875 [first map left] two Medical

Officers of Health reported on the Whitechapel site, and Parliament

approved the scheme in 1876 [second map left - it was modified several times up to

1890]. The Metropolitan Board of Works cleared the site between

1879

and 1881 and remade Cartwright Street and part of Glasshouse Street.

Because it was an awkward site, there were no takers for leasing the

land, so the Peabody Trust bought the area east of the railway viaduct (the spur to the Docks)

for £10,000. There they built nine blocks (A to K) in 1880, each 5

storeys, housing 1372 people. Goad's 1887 insurance map [right]

shows the site before L block was added in 1910. The Whitechapel MOH's

1882 report, somewhat frustrated at the slow progress in slum

clearance, commented

In 1875 [first map left] two Medical

Officers of Health reported on the Whitechapel site, and Parliament

approved the scheme in 1876 [second map left - it was modified several times up to

1890]. The Metropolitan Board of Works cleared the site between

1879

and 1881 and remade Cartwright Street and part of Glasshouse Street.

Because it was an awkward site, there were no takers for leasing the

land, so the Peabody Trust bought the area east of the railway viaduct (the spur to the Docks)

for £10,000. There they built nine blocks (A to K) in 1880, each 5

storeys, housing 1372 people. Goad's 1887 insurance map [right]

shows the site before L block was added in 1910. The Whitechapel MOH's

1882 report, somewhat frustrated at the slow progress in slum

clearance, commentedARTIZANS' AND LABOURERS' DWELLINGS IMPROVEMENT ACT, 1875. The Whitechapel District has already been greatly benefitted by the operations of the above Act, and should all the official representations which have been made to the Metropolitan Board of Works, of the several areas referred to in former Reports, be carried out, will be still further benefitted. The five areas of which the Medical Officer of Health has made official representations, are— 1. The Royal Mint Street Scheme. 2. The Flower and Dean Street Scheme. 3. The Goulston Street Scheme. 4. The Great Pearl Street Scheme. 5. The Bell Lane Scheme. The whole of these several areas, together, comprise near twenty acres. At present, however, only three of these areas have been purchased by the Metropolitan Board of Works, viz., the Royal Mint Street, the Flower and Dean Street, and the Goulston Street areas.All the houses, with the exception of the 'Crown' public house, in Butler's Buildings, and the Schools in Darby Street, within No. 1 area, have been taken down, and blocks of Peabody Buildings have been erected on part of the area. These buildings consist of eleven blocks, and are built to accommodate 286 families. The population in these buildings was, at the end of March last, 1207. Some idea of the wretched condition of the Royal Mint Street area may be formed, when I state that it consisted of about six acres, and contained 450 houses, which were occupied by 3,750 persons, thus allowing to each, on an average, a space of only 8.3 square yards; but in a court called Crown Court, which formed part of this area, and joined Blue Anchor Yard with Glass House Street, there was only an average space of 3.4 square yards for each person. |

Henry

Astley Darbishire was

Peabody's principal architect until 1885 (he had designed their first

scheme, Commercial Street in Spitalfields; the memorial drinking

fountain to his patroness Baroness Angela Burdett-Coutts - then the

richest woman in England, and known as 'Queen of the poor' - in

Victoria

Park is also his work). He undoubtedly created a recognisable, standard

formula for their estates, though the constraints of the sites that the

MBW had prepared often shaped the design, and the tricky Whitechapel

estate is one of his most flexible plans. Less concerned with

streetscape - so that his buildings look grim from the road - they

concentrated on inward-facing blocks with internal spaces between them.

He was keen on the use of coloured bricks for string courses and other

details - he read a paper on the subject to the RIBA in 1865. (Pictured

is the standard street entrance door used after

1875.)

Henry

Astley Darbishire was

Peabody's principal architect until 1885 (he had designed their first

scheme, Commercial Street in Spitalfields; the memorial drinking

fountain to his patroness Baroness Angela Burdett-Coutts - then the

richest woman in England, and known as 'Queen of the poor' - in

Victoria

Park is also his work). He undoubtedly created a recognisable, standard

formula for their estates, though the constraints of the sites that the

MBW had prepared often shaped the design, and the tricky Whitechapel

estate is one of his most flexible plans. Less concerned with

streetscape - so that his buildings look grim from the road - they

concentrated on inward-facing blocks with internal spaces between them.

He was keen on the use of coloured bricks for string courses and other

details - he read a paper on the subject to the RIBA in 1865. (Pictured

is the standard street entrance door used after

1875.)

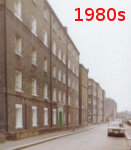

Between 1884 and 1890

six other sites, west of the

viaduct, were sold off, resulting in a total estate population of

3,600, each block accommodating over 100 - much the same density as

before. Lord Rothschild (closely connected with the Royal Mint

Refinery - the family had taken on the lease in 1852) built a

5-storey 'staircase' block, the (Royal) Albert Buildings, on the

newly-formed Cartwight Street for the Four Per Cent

Industrial Dwellings Company

(architect Nathan S. Joseph), an ugly building with heavy terra cotta

ornamentation [rear view pictured right].

Between 1884 and 1890

six other sites, west of the

viaduct, were sold off, resulting in a total estate population of

3,600, each block accommodating over 100 - much the same density as

before. Lord Rothschild (closely connected with the Royal Mint

Refinery - the family had taken on the lease in 1852) built a

5-storey 'staircase' block, the (Royal) Albert Buildings, on the

newly-formed Cartwight Street for the Four Per Cent

Industrial Dwellings Company

(architect Nathan S. Joseph), an ugly building with heavy terra cotta

ornamentation [rear view pictured right].

On the south-east corner of the development, at 54 Glasshouse Street, was the cocoa factory of Peek Bros & Winch - detail right

from Goad's 1887 insurance map. Their head office until 1958 was at 20

Eastcheap, built in 1870 on a corner site with a sculpture [far right] of three Arab-led camels bearing tea, coffee and spices - now HSBC premises) - see here and here

for the company history: until they re-united in 1895, rival family

companies with London and Liverpool bases, major players in the tea

trade but also dealing in coffee, cocoa, chocolate and spices. Francis

Peek (1834-99), who ran the company from 1870, was a philanthropist who

gave over £500k to charitable and religious causes, built Holy Trinity

Church in Beckenham, was a member of the London School Board and

chairman of the Howard Association, forerunner of the Howard League for Penal Reform.

On the south-east corner of the development, at 54 Glasshouse Street, was the cocoa factory of Peek Bros & Winch - detail right

from Goad's 1887 insurance map. Their head office until 1958 was at 20

Eastcheap, built in 1870 on a corner site with a sculpture [far right] of three Arab-led camels bearing tea, coffee and spices - now HSBC premises) - see here and here

for the company history: until they re-united in 1895, rival family

companies with London and Liverpool bases, major players in the tea

trade but also dealing in coffee, cocoa, chocolate and spices. Francis

Peek (1834-99), who ran the company from 1870, was a philanthropist who

gave over £500k to charitable and religious causes, built Holy Trinity

Church in Beckenham, was a member of the London School Board and

chairman of the Howard Association, forerunner of the Howard League for Penal Reform.

The processions are from English Martyrs Church, Prescot Street; right in John FIsher Street (with the closed railways viaduct in the background).

The processions are from English Martyrs Church, Prescot Street; right in John FIsher Street (with the closed railways viaduct in the background).

In

1940 'K' block was destroyed by a German bomb. Seventy residents and

visitors were killed - they are named on the nearby memorial [left]. As this

1940s picture, and maps [right] show, the block was not rebuilt. In I Know a Rotten

Place (Arlington 1975) Bryan Breed, evacuated from the

estate, describes returning to see it as

filthy, grimy and lovely as ever, with gaping holes or rough brick walls to fill

up the gaps in terraces, but still K block was Peabody's only

tragedy. (The book's title comes from an evacuees' song,

sung to the tune of Old Soldiers

Never Die.)

In

1940 'K' block was destroyed by a German bomb. Seventy residents and

visitors were killed - they are named on the nearby memorial [left]. As this

1940s picture, and maps [right] show, the block was not rebuilt. In I Know a Rotten

Place (Arlington 1975) Bryan Breed, evacuated from the

estate, describes returning to see it as

filthy, grimy and lovely as ever, with gaping holes or rough brick walls to fill

up the gaps in terraces, but still K block was Peabody's only

tragedy. (The book's title comes from an evacuees' song,

sung to the tune of Old Soldiers

Never Die.)

Left is the Square today, and blocks A, E and L. On the corner of the

estate the Peabody Group recently built the Whitechapel Learning

Centre, to a 'green' brief, providing a bright building in a drab

setting. It is a 'threshold centre' with a nursery, and courses in IT,

literacy and numeracy linked to the creation of employment

opportunities [pictured here, and in

the snow of February 2009].

'D'

block, which stood in the centre of the estate, has now been demolished

to create open space; it lay behind 'G' and 'H' blocks, pictured

here from Cartwright Street. See here for a 1973 view of the railway viaduct to the Docks before its demolition.

Left is the Square today, and blocks A, E and L. On the corner of the

estate the Peabody Group recently built the Whitechapel Learning

Centre, to a 'green' brief, providing a bright building in a drab

setting. It is a 'threshold centre' with a nursery, and courses in IT,

literacy and numeracy linked to the creation of employment

opportunities [pictured here, and in

the snow of February 2009].

'D'

block, which stood in the centre of the estate, has now been demolished

to create open space; it lay behind 'G' and 'H' blocks, pictured

here from Cartwright Street. See here for a 1973 view of the railway viaduct to the Docks before its demolition. Back to History page