Rosemary Lane (now Royal Mint Street)

Rosemary Lane (now Royal Mint Street)

Rosemary

Lane (originally Hog Lane, or Hoggestrete) was the continuation of what

is now

Cable Street, running from the junction with Dock Street and Leman

Street towards the Tower of London. See here

for the history of the Royal Mint site - once an abbey, then the navy's

victualling yard, and then the 'New Mint'. Rosemary Lane was renamed

Royal Mint Street in

1850. In the same period, for prudish reasons, Petticoat Lane was renamed

Middlesex Street. Both are best known for their street markets - the

difference being that Rosemary Lane, as these extracts show, was

primarily for second-hand trade, and is now long-gone.

A

grant was recorded on 31 October 1631 to William Bawdrick and

Roger Hunt of the King's interest in certain tenements in Rosemary

Lane. Middlesex, the lease of which was taken by Horatio Franchotti, an

alien, but discovered and prosecuted for on His Majesty's behalf.

Some claim that the

poet Edmund

Spenser (1552-99) was born between Rosemary Lane and East

Smithfield, though this is disputed (perhaps it was West Smithfield, in the City).

He attended Merchant

Taylors' School,

founded in the City in 1561 by Richard Hills, master of the Company.

Hills also endowed a group of cottages on the north side of Rosemary

Lane as almshouses for fourteen elderly women, who were to receive 1s.

4d. per

week, under his will, and £8. 15s. annually from

the Company. Alderman Ratcliffe of the Company added

the

benefaction of one hundred loads of timber.

Some claim that the

poet Edmund

Spenser (1552-99) was born between Rosemary Lane and East

Smithfield, though this is disputed (perhaps it was West Smithfield, in the City).

He attended Merchant

Taylors' School,

founded in the City in 1561 by Richard Hills, master of the Company.

Hills also endowed a group of cottages on the north side of Rosemary

Lane as almshouses for fourteen elderly women, who were to receive 1s.

4d. per

week, under his will, and £8. 15s. annually from

the Company. Alderman Ratcliffe of the Company added

the

benefaction of one hundred loads of timber.

1649 - death of Richard

Brandon

1649 - death of Richard

Brandon

The

public executioner - who beheaded King Charles I and a number of

leading Royalists - died in Rosemary Lane - see more about him here. The burial registers of St

Mary Whitechapel (where he was buried - now Altab Ali Park) record

1649, June 21st. Rich. Brandon, a man out of Rosemary Lane.... this R. Brandon is supposed to have cut off the head of Charles the First.

Another

account adds:

He likewise confessed that he had thirty pounds for his pains,

all paid him in half-crowns, within an hour after the blow was given;

and that he had an orange stuck full of cloves, and a hankercher, out

of the king's pocket, so soon as he was carried off from the scaffold,

for which orange he was proffered twenty shillings by a gentleman in

Whitehall, but refused the same, and afterward sold it for ten

shillings in Rosemary Lane.

1641 - prophets of the end time

I will give unto my two witnesses, and they shall prophesy a thousand two hundred and threescore days, clothed in sackcloth (Revelation 11.3)

In

January 1641 two Colchester weavers, Richard Farnham and John Bull

[pictured], by a strange providence of almighty God (as a contemporary source puts it) died of the

plague in the house in Rosemary Lane where they regularly met. They

had declared themselves to be the two great prophets who must come

before the end of the world of Revelation speaks, and had been

imprisoned in Old and New Bridewell gaols respectively. A pamphlet of

1642 describes their strange prophecies, and the Scriptures

which they most blasphemously wrested, to the seducing of divers

proselytes, who yet remaine obstinate, and confidently affirme that

they are risen from the dead, and gone in vessels of bullrushes to

convert the tenne Tribes...

In

January 1641 two Colchester weavers, Richard Farnham and John Bull

[pictured], by a strange providence of almighty God (as a contemporary source puts it) died of the

plague in the house in Rosemary Lane where they regularly met. They

had declared themselves to be the two great prophets who must come

before the end of the world of Revelation speaks, and had been

imprisoned in Old and New Bridewell gaols respectively. A pamphlet of

1642 describes their strange prophecies, and the Scriptures

which they most blasphemously wrested, to the seducing of divers

proselytes, who yet remaine obstinate, and confidently affirme that

they are risen from the dead, and gone in vessels of bullrushes to

convert the tenne Tribes...

According

to William Hurd, in A new universal history of the religious rites,

ceremonies and customs, of the whole world (Hemingway 1799, page 815), it was also in Rosemary

Lane - the same house? - that in

February 1652 cousins and journeyman-tailors John Reeve (1608-1658) and Lodowicke Muggleton

(1609-98, painting left by William Wood), influenced by the Ranters,

received 'the Third Commission' from God relating to the same text from

Revelation, of which Muggleton was to be the 'mouth'. In a public

house in The Minories, on Tower Hill, and elsewhere, they proposed a new scheme

of religion - though this was never systematic.

According

to William Hurd, in A new universal history of the religious rites,

ceremonies and customs, of the whole world (Hemingway 1799, page 815), it was also in Rosemary

Lane - the same house? - that in

February 1652 cousins and journeyman-tailors John Reeve (1608-1658) and Lodowicke Muggleton

(1609-98, painting left by William Wood), influenced by the Ranters,

received 'the Third Commission' from God relating to the same text from

Revelation, of which Muggleton was to be the 'mouth'. In a public

house in The Minories, on Tower Hill, and elsewhere, they proposed a new scheme

of religion - though this was never systematic.  Muggleton published A true interpretation of the eleventh

chapter of the Revelation of St. John, and other texts in that book

as also many other places of Scripture whereby is unfolded, and

plainly declared the whole councel of God concerning Himself, the

Devil, and all mankinde, from the foundation of the world, to all

eternity. The

Presbyterians and Independents sought to have them restrained, and

Oliver Cromwell ordered them to be whipped through the streets;

later, after Reeve's death, Muggleton was imprisoned in the stocks.

They believed they had been given authority to anathematise false

believers, and the Quakers were particular targets: in Muggleton's

1663 tract The Neck of The Quakers Broken he

wrote He hath put the two-edged Sword of His Spirit into my

Mouth, that whosoever I pronounce cursed through my Mouth, is cursed

to Eternity. A 'tract war' followed, with rejoinders from the Quaker leader

Isaac Pennington.

Muggleton published A true interpretation of the eleventh

chapter of the Revelation of St. John, and other texts in that book

as also many other places of Scripture whereby is unfolded, and

plainly declared the whole councel of God concerning Himself, the

Devil, and all mankinde, from the foundation of the world, to all

eternity. The

Presbyterians and Independents sought to have them restrained, and

Oliver Cromwell ordered them to be whipped through the streets;

later, after Reeve's death, Muggleton was imprisoned in the stocks.

They believed they had been given authority to anathematise false

believers, and the Quakers were particular targets: in Muggleton's

1663 tract The Neck of The Quakers Broken he

wrote He hath put the two-edged Sword of His Spirit into my

Mouth, that whosoever I pronounce cursed through my Mouth, is cursed

to Eternity. A 'tract war' followed, with rejoinders from the Quaker leader

Isaac Pennington.

Muggletonian activity continued, though they never met for

organised worship, or held public meetings, or evangelised, but they had a cetrain influence - including possibly on William Blake

- and became more vocal in the 19th century. Activities centred on

reading rooms, where there was discussion, reading and singing,

including one at 7 New Street, Bishopsgate, purported to be the site of

Muggleton's birth (moved to Worship Street, Finsbury Square after the

First World War) and also in Derbyshire. The last trustee, Philip

Noakes, died in 1979 and bequeathed many records and papers. There is a very thorough website here.

1720

John

Strype's Survey

of London spoke of the small,

nasty and beggarly

streets around The Minories.

Daniel Defoe Colonel

Jack (1722)

Daniel Defoe Colonel

Jack (1722)

Several works by, or attributed to, Daniel Defoe

(1659-1731) mention the area. Colonel

Jack had

his Breeding near Goodman's-fields and spent his

youth rambling about

Rosemary Lane and Ratcliff. After his nurse died, Jack and his

companions

lived for some years each winter in the glasshouse near Rosemary Lane;

on one

occasion they went to Rag Fair and bought two pairs of shoes and

stockings for

5d., and went on to a

boiling Cook's in Rosemary Lane where they

found cheap fare.

Alexander

Pope and The

Dunciad

pictured: Pope & his dog Bounce, 1718

Alexander

Pope and The

Dunciad

pictured: Pope & his dog Bounce, 1718

Pope's satire of 1728 (with subsequent editions in 1735 and 1743) was a protest against the tasteless, counterfeit, second-hand standards of the journalism and poetry of his day - the worship of the goddess Dulness. He used images of low-life venues, shifting from Grub Street in the west to Rosemary Lane's Rag Fair in the east, and included these lines:

He

added the note: Rag-fair is

a place near the Tower of London, where

old cloaths and frippery are sold. A contemporary

commentator added Much

of the

clothing that was sold there was stolen; the market was also the final

destination of all cast-off rags, in an epoch notorious for its

careless habits and for seldom or never changing its linen. See

further Pat Rogers Hacks and Dunces

(1980), exploring the detail of this imagery.

The

Daily Gazetteer,

2 August 1736

| Late

on Friday night, and early on Saturday morning, a great disturbance

happen’d in Rosemary-lane, near Rag-fair, where upwards of 150 men

assembled in a riotous manner with clubs, and other unlawful weapons,

and oblig’d all the house-keepers in Rose-mary-lane, and the parts

adjacent, to put lights in their windows, otherwise they would pull

their houses down, which put the people in the greatest consternation;

so that the whole place appear’d with lights at each window; and some

few that had none, got their windows broke to pieces. The mob went from

Rosemary-lane to Well-street by the Watch-house, and pull’d down the

house of one Welden, a cook, at the sign of the Bull and Butcher, and

broke the houshold goods all to pieces. By this time Clifford William

Phillips, of Goodman’s-fields, and Richard Farmer, of

Well-Close-square, Esqrs., two of his Majesty’s Justices of the Peace,

had procured a party of Grenadiers from the Tower, with a Commanding

Officer, in order to disperse the mob, but to no purpose, for they went

from Well-street into Rag-Fair, and demolish’d the Queen’s Head, and a

cook’s shop (the master of which is an Irish man) in Mill-yard, and a

tavern hard by, kept by Irish people: From Rag-Fair they went to

Church-lane, and demolish’d the White-Hart Ale-house, and from thence

to White-Lion-street, and demolish’d the Gentleman and Porter, they

being all houses where Irishmen used. The general cry was, while they

were committing these outrages, Down with the wild Irish. Justice

Phillips, and the commanding officers from the Tower, had their swords

drawn, and desired the mob quietly to depart; but they could not

disperse them till towards four o’clock on Saturday morning, when John

Brundit, Edward Dudley, William Ormond, Robert Maccay, Thomas Batteroy,

and Robert Page, were apprehended, and on Saturday night were committed

to Newgate. A party of his Majesty’s Horse-Guards, a party of the Horse Grenadiers, and two parties of Foot, patrole every night in the streets of Spital-fields, White-chappel, Rag-Fair, &c. Last Saturday about 16 other persons were apprehended, on suspicion of being concern’d in the said riots. |

The

Public Advertiser, 17 February 1756

Two late 18th century images of Rag Fair

Bowles'

print of 1795 [left] is entitled High

Change, Rag Fair. It

depicts the City end of the market, near Wellclose Square. The term

'high (ex)change' was borrowed from the financial markets, to depict

the period of maximum activity, when the male stallholders would take

over from the women and children. The market traded every day except

Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath.

Bowles'

print of 1795 [left] is entitled High

Change, Rag Fair. It

depicts the City end of the market, near Wellclose Square. The term

'high (ex)change' was borrowed from the financial markets, to depict

the period of maximum activity, when the male stallholders would take

over from the women and children. The market traded every day except

Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath.

Rowlandson's

watercolour [right] is from a few years later. The detail of the shop

signs shows the prominence of Jews in this trade:

'MOSES

MONCERA Old Hats & Wigs bought Sold or Exchanged';

'WIDOW LEVY dealer in Old Breeches'; 'Most money given for Bad Silver

MOSES ESTARDO'; PETER SMOUTCH Mony Rais'd on Good Security'. It was

commonly believed that Jews were responsible for most counterfeit

coinage. Several of the dealers standing by their

stalls are

bearded, wear long

coats and carry piles of hats on their heads, all features traditional

to the iconographic depiction of street Jews.

Rowlandson's

watercolour [right] is from a few years later. The detail of the shop

signs shows the prominence of Jews in this trade:

'MOSES

MONCERA Old Hats & Wigs bought Sold or Exchanged';

'WIDOW LEVY dealer in Old Breeches'; 'Most money given for Bad Silver

MOSES ESTARDO'; PETER SMOUTCH Mony Rais'd on Good Security'. It was

commonly believed that Jews were responsible for most counterfeit

coinage. Several of the dealers standing by their

stalls are

bearded, wear long

coats and carry piles of hats on their heads, all features traditional

to the iconographic depiction of street Jews.

In Lights

and Shadows of

London Life (1842) James Grant describes a visit to

Rag Fair:

The buyers and

sellers...are thorough

men of business. They are persons of few words; they have no time for

talking.... "How much?" says Moses, snatching a coat, or waistcoat, or

pair of trousers, from the arms or shoulders of Solomon, and giving it

a hasty inspection. "Van and sixpensh," answers the later. "Take van

and twopensh?" says the former. "No," remarks Solomon; and thereupon

Moses tosses the article of "old clo" contemptuously on his arms and

marches away with a snarlish expression of countenance.

The

articles of commerce by no means belie the name. There is no expressing

the poverty of the goods, nor yet their cheapness. A distinguished

merchant engaged with a purchaser observing me look on him with great

attention, called out to me, as his customer was going off with his

bargain, to observe that man, 'for,' says he, 'I have actually clothed

him for fourteen pence.' It was here, we believe, that

purchasers were

allowed to dip in a sack for old wigs—a penny the dip. Noblemen's suits

come here at last, after undergoing many vicissitudes.

Pennant's

book can be read here.

However, Joseph Nightingale's London

and Middlesex (1815) remarks

| The

idea which Mr.

Pennant formed of this place will be found to have been extremely

erroneous; "the poverty of the goods and their cheapness," which he

mentions, no longer exist. That a man may be wholly clothed here

for fourteen pence is a pure fiction. It is true, that during

a

part of every afternoon the middle of the street is nearly filled with

a number of Jews and other persons selling clothes, and second hand

various articles of dress at a very low rate; hut the houses in

Rosemary Lane, or the so called Rag Fair, are mostly occupied

by wholesale dealers in clothes, who used to export them to our

colonies, and to South America. In several Exchanges, or large covered

buildings, fitted up with counters, &c. there are good shops,

and

the annual circulation of money in the purliens of this place, is

really astonishing, considering the articles sold, although their

cheapness bears no kind of proportion to Mr. Pennant's

conjectures. |

|

When Sir Jeffery raised the cry of 'old wigs', the collecting of which

formed his chief occupation, he had a peculiarly droll way of clapping

his hand to his mouth, and he called 'old wigs, wigs, wigs!' in every

doorway. Some he disposed of privately, the rest he sold to the dealers

in 'Rag-fair'. In those days, 'full bottoms' were worn by almost every

person, and it was no uncommon thing to hear sea-faring persons, or

others exposed to the cold, exclaim, "Well, winter's at hand, and I

must e'en go to Rosemary-lane, and have a dip

for a wig." This 'dipping for wigs' was nothing more than putting your

hand into a large barrel and pulling one up; if you liked it you paid

your shilling, if not, you dipped again, and paid sixpence more, and so

on. Then, also, the curriers used them for cleaning the waste, &c.

off the leather, and I have no doubt would use them now if they could

get them. |

| A

missionary who recently explored Rag-fair, reported that a

man and his wife might be clothed from head to foot for from 10s. to 15s.

Another

missionary stated that 8s. would buy every article of clothing required

by

either a man or a woman, singly.... A third missionary reported: "There

is as great a

variety of articles in pattern, and shape, and size, as I think could

be found

in any draper's shop in London." The mother may go to 'Rag-fair'

with the whole of her family, both boys and girls, - yes, and her

husband, too,

and for a very few shillings deck them out from top to toe. I have no

doubt that

for a man and his wife, and five or six children, £1 at their disposal,

judiciously laid out, would purchase them all an entire change. This

may appear

to some an exaggeration: but I actually overheard a conversation in

which two

women were trying to bargain for a child's frock; the sum asked for it

was 1½d.

and

the sum offered was a penny, and they parted on the

difference.

The following is the copy of the bill delivered by the dealer to one of the missionaries, who was requested to supply a suit of clothes for a man and woman whom he had persuaded to get married several years after the right time:-

The man had been educated, and could speak no fewer than five languages; by profession he was, then, however, nothing but a dust-hill raker. The bill delivered for the bride's costume was as follows

The goods were selected by the missionary, and at the bottom of the bills the merchant marked:- "P.S.-Will be very happy to supply as many as you can find at the same prices." |

Henry

Mayhew London Labour

and the London Poor (1861)

Henry

Mayhew London Labour

and the London Poor (1861)

A Cyclopædia of the Condition

and Earnings of Those that will work, those that cannot work, and those that will not work

Henry

Mayhew was an indefatigable chronicler of the London scene. He has his

prejudices - including a strong anti-semitic streak - but provides much

valuable detail of social and economic conditions.

Rosemary

Lane Rosemary-lane,

which has in vain been re-christened Royal Mint-street, is from half to

three-quarters of a mile long—that is, if we include only the portion

which runs from the junction of Leman and Dock streets (near the London

Docks) to Sparrow-corner, where it abuts on the Minories. Beyond the

Leman-street termination of Rosemary-lane, and stretching on into

Shadwell, are many streets of a similar character as regards the street

and shop supply of articles to the poor; but as the old clothes trade

is only occasionally carried on there, I shall here deal with

Rosemary-lane proper.

Rosemary-lane,

which has in vain been re-christened Royal Mint-street, is from half to

three-quarters of a mile long—that is, if we include only the portion

which runs from the junction of Leman and Dock streets (near the London

Docks) to Sparrow-corner, where it abuts on the Minories. Beyond the

Leman-street termination of Rosemary-lane, and stretching on into

Shadwell, are many streets of a similar character as regards the street

and shop supply of articles to the poor; but as the old clothes trade

is only occasionally carried on there, I shall here deal with

Rosemary-lane proper.This lane partakes of some of the characteristics of Petticoat-lane, but without its so strongly marked peculiarities. Rosemary-lane is wider and airier, the houses on each side are loftier (in several parts), and there is an approach to a gin palace, a thing unknown in Petticoat-lane: there is no room for such a structure there. Rosemary-lane, like the quarter I have last described, has its off-streets, into which the traffic stretches. Some of these off-streets are narrower, dirtier, poorer in all respects than Rosemary-lane itself, which indeed can hardly be stigmatized as very dirty. These are Glasshouse-street, Russell-court, Hairbrine-court, Parson's-court, Blue Anchor-yard (one of the poorest places and with a half-built look), Darby-street, Cartwright-street, Peter's-court, Princes-street, Queen-street, and beyond these and in the direction of the Minories, Rosemary-lane becomes Sharp's-buildings and Sparrow-corner. There are other small non-thoroughfare courts, sometimes called blind alleys, to which no name is attached, but which are very well known to the neighbourhood as Union-court, &c.; but as these are not scenes of street-traffic, although they may be the abodes of street-traffickers, they require no especial notice. The dwellers in the neighbourhood or the off-streets of Rosemary-lane, differ from those of Petticoat-lane by the proximity of the former place to the Thames. The lodgings here are occupied by dredgers, ballast-heavers, coal-whippers, watermen, lumpen, and others whose trade is connected with the river, as well as the slop-workers and sweaters working for the Minories. The poverty of these workers compels them to lodge wherever the rent of the rooms is the lowest. As a few of the wives of the ballast-heavers, &c., are street-sellers in or about Rosemary-lane, the locality is often sought by them. About Petticoat-lane the off-streets are mostly occupied by the old clothes merchants. In Rosemary-lane is a greater street-trade, as regards things placed on the ground for retail sale, &c., than in Petticoat-lane; for though the traffic in the last-mentioned lane is by far the greatest, it is more connected with the shops, and fewer traders whose dealings are strictly those of the street alone resort to it. Rosemary-lane, too, is more Irish. There are some cheap lodging-houses in the courts, &c., to which the poor Irish flock; and as they are very frequently street sellers, on busy days the quarter abounds with them. At every step you hear the Erse tongue, and meet with the Irish physiognomy; Jews and Jewesses are also seen in the street, and they abound in the shops. The street-traffic does not begin until about one o'clock, except as regards the vegetable, fish, and oyster-stalls, &c.; but the chief business of this lane, which is as inappropriately as that of Petticoat is suitably named, is in the vending of the articles which have often been thrown aside as refuse, but from which numbers in London wring an existence. One side of the lane is covered with old boots and shoes; old clothes, both men's, women's, and children's; new lace for edgings; and a variety of cheap prints and muslins (also new); hats and bonnets; pots, and often of the commonest kinds; tins; old knives and forks, old scissors, and old metal articles generally; here and there is a stall of cheap bread or American cheese, or what is announced аs American; old glass; different descriptions of second-hand furniture of the smaller size, such as children's chairs, bellows, &c. Mixed with these, but only very scantily, are a few bright-looking swag-barrows, with china ornaments, toys, &c. Some of the wares are spread on the ground on wrappers, or pieces of matting or carpet; and some, as the pots, are occasionally placed on straw. The cotton prints are often heaped on the ground; where are also ranges or heaps of boots and shoes, and piles of old clothes, or hats, or umbrellas. Other traders place their goods on stalls or barrows, or over an old chair or clothes-horse. And amidst all this motley display the buyers and sellers smoke, and shout, and doze, and bargain, and wrangle, and eat and drink tea and coffee, and sometimes beer. Altogether Rosemary-lane is more of a street market than is Petticoat-lane. This district, like the one I have first described, is infested with young thieves and vagrants from the neighbouring lodging-houses, who may be seen running about, often bare footed, bare-necked, and shirtless, but "larking" one with another, and what mav be best understood as "full of fun." In what way these lads dispose of their plunder, and how their plunder is in any way connected with the trade of these parts, I shall show in my account of the Thieves. One pickpocket told me that there was no person whom he delighted so much to steal from as any Petticoat-laner with whom he had professional dealings! In Rosemary-lane there is a busy Sunday morning trade; there is a street trade, also, on the Saturday afternoons, but the greater part of the shops are then closed, and the Jews do not participate in the commerce until after sunset. The two marts [Petticoat Lane & Rosemary Lane] I have thus fully described differ from all other street-markets, for in these two second-hand garments, and second-hand merchandize generally (although but in a small proportion), are the grand staple of the traffic. At the other street-markets, the second-hand commerce is the exception. Of the Street-Sellers of Petticoat and Rosemary-Lanes Immediately connected with the trade of the central mart for old clothes are the adjoining streets of Petticoat-lane, and those of the not very distant Rosemary-lane. In these localities is a second-hand garment-seller at almost every step, but the whole stock of these traders, decent, frowsy, half-rotten, or smart and good habilments, has first passed through the channel of the Exchange. The men who sell these goods have all bought them at the Exchange—the exceptions being insignificant—so that this street-sale is but an extension of the trade of the central mart, with the addition that the wares have been made ready for use. A

cursory observation might lead an inexperienced person to the

conclusion, that these old clothes traders who are standing by the

bundles of gowns, or lines of coats, hanging from their doorposts, or

in the place from which the window has been removed, or at the sides of

their houses, or piled in the street before them, are drowsy

people,

for they seem to sit among their property, lost in thought, or caring

only for the fumes of a pipe. But let any one indicate, even by an

approving glance, the likelihood of his becoming a customer, and see if

there be any lack of diligence in business. Some, indeed,

pertinaciously invite attention to their wares; some (and often

welldressed women) leave their premises a few yards to accost a

stranger pointing to a "good dresscoat" or "an excellent frock" (coat).

I am told that this practice is less pursued than it was, and it seems

that the solicitations are now addressed chiefly to strangers. These

strangers, persons happening to be passing, or visitors from curiosity,

are at once recognised; for as in all not very extended localities,

where the inhabitants pursue a similar calling, they are, as regards

their knowledge of one another, as the members of one family. Thus a

stranger is as easily recognised as he would be in a little rustic

hamlet where a strange face is not seen once a quarter. Indeed so

narrow are some of the streets and alleys in this quarter, and so

little is there of privacy, owing to the removal, in warm weather, even

of the casements, that the room is commanded in all its domestic

details; and as among these details there is generally a further

display of goods similar to the articles outside, the jammedup places

really look like a great family house with merely a sort of channel,

dignified by the name of a street, between the right and left suites of

apartments. In

one off-street, where on a Sunday there is a

considerable demand for Jewish sweet-meats by Christian boys, and a

little sly, and perhaps not very successful gambling on the part of the

ingenuous youth to possess themselves of these confectionaries at the

easiest rate, there are some mounds of builders' rubbish upon which, if

an inquisitive person ascended, he could command the details of the

upper rooms, probably the bed chambers—if in their crowded apartments

these traders can find spaces for beds. It must not be supposed that old clothes are more than the great staple of the traffic of this district. Wherever persons are assembled there are certain to be purveyors of provisions and of cool or hot drinks for warm or cold weather. The interior of the Old Clothes Exchange has its oyster-stall, its fountain of ginger-beer, its coffeehouse, and ale-house, and a troop of peripatetic traders, boys principally, carrying trays. Outside the walls of the Exchange this trade is still thicker. A Jew boy thrusts a tin of highly-glazed cakes and pastry under the people's noses here; and on the other side a basket of oranges regales the same sense by its proximity. At the next step the thoroughfare is interrupted by a gaudylooking ginger-beer, lemonade, raspberryade, and nectar fountain; "a halfpenny a glass, a halfpenny a glass, sparkling lemonade!" shouts the vendor as you pass. The fountain and the glasses glitter in the sun, the varnish of the wood-work shines, the lemonade really does sparkle, and all looks clean—except the owner. Close by is a brawny young Irishman, his red beard unshorn for perhaps ten days, and his neck, where it had been exposed to the weather, a far deeper red than his beard, and he is carrying a small basket of nuts, and selling them as gravely as if they were articles suited to his strength. A little lower is the cry, in a woman's voice, "Fish, fried fish! Ha'penny; fish, fried fish!" and so monotonously and mechanically is it ejaculated that one might think the seller's life was passed in uttering these few words, even as a rook's is in crying "Caw, caw." Here I saw a poor Irishwoman who had a child on her back buy a piece of this fish (which may be had "hot" or "cold"), and tear out a piece with her teeth, and this with all the eagerness and relish of appetite or hunger; first eating the brown outside and then sucking the bone. I never saw fish look firmer or whiter. That fried fish is to be procured is manifest to more senses than one, for you can hear the sound of its being fried, and smell the fumes from the oil. In an open window opposite frizzle on an old tray, small pieces of thinly-cut meat, with a mixture of onions, kept hot by being placed over an old pan containing charcoal. In another room a mess of batter is smoking over a grate. "Penny a lot, oysters," resounds from different parts. Some of the sellers command two streets by establishing their stalls or tubs at a corner. Lads pass, carrying sweet-stuff on trays. I observed one very dark-eyed Hebrew boy chewing the hard-bake he vended—if it were not a substitute—with an expression of great enjoyment. Heaped--up trays of fresh-looking sponge-cakes are carried in tempting pyramids. Youths have stocks of large hardlooking biscuits, and walk about crying, "Ha'penny biscuits, ha'penny; three a penny, biscuits;" these, with a morsel of cheese, often supply a dinner or a luncheon. Dates and figs, as dry as they are cheap, constitute the stock in trade of other street-sellers. "Coker-nuts" are sold in pieces and entire; the Jew boy, when he invites to the purchase of an entire nut, shaking it at the ear of the customer. I was told by a costermonger that these juveniles had a way of drumming with their fingers on the shell so as to satisfy a "green" customer that the nut offered was a sound one. Such

are the summer eatables and drinkables which I have lately seen vended

in the Petticoat-lane district. In winter there are, as long as

daylight

lasts—and in no other locality perhaps does it last so short a

time—other street provisions, and, if possible, greater zeal in selling

them, the hours of business being circumscribed. There is then the

potato-can and the hot elder-wine apparatus, and smoking pies and

puddings, and roasted apples and chestnuts, and walnuts, and the

several fruits which ripen in the autumn—apples, pears, &c. Hitherto

I have spoken only of such eatables and drinkables as are ready for

consumption, but to these the trade in the Petticoat-lane district is

by no means confined. There is fresh fish, generally of the cheaper

kinds, and smoked or dried fish (smoked salmon, moreover, is sold

ready cooked), and costermongers' barrows, with their loads of

green

vegetables, looking almost out of place amidst the surrounding

dinginess. The cries of "Fine cauliflowers," "Large penny cabbages,"

"Eight a shilling, mackarel," "Eels, live eels," mix strangely with the

hubbub of the busier street. Other

street-sellers also abound. You

meet one man who says mysteriously, and rather bluntly, "Buy a good

knife, governor." His tone is remarkable, and if it attract attention,

he may hint that he has smuggled goods which he must sell anyhow. Such

men, I am told, look out mostly for seamen, who often resort to

Petticoat-lane; for idle men like sailors on shore, and idle

uncultivated men often love to lounge where there is bustle. Pocket and

pen knives and scissors, "Penny a piece, penny a pair," rubbed over

with oil, both to hide and prevent rust, are carried on trays, and

spread on stalls, some stalls consisting of merely a tea-chest lid on a

stool. Another man, carrying perhaps a sponge in his hand, and

well-dressed, asks you, in a subdued voice, if you want a good razor,

as if he almost suspected that you meditated suicide, and were looking

out for the means! This is another ruse to introduce smuggled (or

"duffer's") goods. Account-books are hawked. "Penny-a-quire," shouts

the itinerant street stationer (who, if questioned, always declares he

said "Penny half quire"). "Stockings, stockings, two pence a pair."

"Here's your chewl-ry; penny, a penny; pick'em and choose 'em." [I may

remark that outside the window of one shop, or rather parlour, if there

be any such distinction here, I saw the handsomest, as far as I am able

to judge, and the best cheap jewellery I ever saw in the streets.]

"Pencils, sir, pencils; steel-pens, steel-pens; ha'penny, penny;

pencils, steel-pens; sealing-wax, wax, wax, wax!" shouts one, "Green

peas, ha'penny a pint!" cries another. These

things, however, are

but the accompaniments of the main traffic. But as such things

accompany all traffic, not on a small scale, and may be found in almost

every metropolitan thoroughfare, where the police are not required, by

the householders, to interfere, I will point out, to show the

distinctive character of the street-trade in this part, what is not

sold and not encouraged. I saw no old books. There were no flowers; no

music, which indeed could not be heard except at the outskirts of the

din; and no beggars plying their vocation among the trading class. Another

peculiarity pertaining alike to this shop and street locality is, that

everything is at the veriest minimum of price; though it may not be

asked, it will assuredly be taken. The bottle of lemonade which is

elsewhere a penny is here a halfpenny. The tarts, which among the

street-sellers about the Royal Exchange are a halfpenny each, are here

a farthing. When lemons are two a-penny in St. George's-market,

Oxford-street, as the long line of street stalls towards the western

extremity is called—they are three and four a-penny in Petticoat and

Rosemary lanes. Certainly there is a difference in size between the

dearer and the cheaper tarts and lemons, and perhaps there is a

difference in quality also, but the rule of a minimized cheapness has

no exceptions in this cheaptrading quarter.... further description of Petticoat Lane follows - and see here for detailed accounts of various types of second-hand trade |

There are further

Victorian accounts of the area in Walter Thornbury Old and

New London,

vol.2 (1878) and Henry Wheatley London

Past and Present (1891), who

comments Royal Mint Street has hardly so evil a

reputation as Rosemary Lane, but it is a squalid place, lined with old

clothes' shops and stalls, and on Sunday mornings the aspect of Rag

Fair, as it is still commonly called, is anything but edifying. A

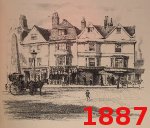

revised version of this work by Wheatley and T.R. Way, Later Reliques

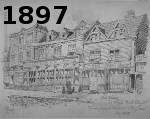

of Old London (G Bell 1897) includes this 1887 plate of Sharpe's Row, numbers 2, 3, 3½ & 4, in Royal Mint Street. Right

are three other drawings and sketches from the period - 1871 by Charles

James Richardson, 1880 by John Philipps Emslie and 1897 by Robert

Randoll - and a photograph of 1900. The

market continued in Royal Mint Street until 1911, but the area became dominated by railway activity [see below]. Petticoat Lane, of course, is still going strong!

There are further

Victorian accounts of the area in Walter Thornbury Old and

New London,

vol.2 (1878) and Henry Wheatley London

Past and Present (1891), who

comments Royal Mint Street has hardly so evil a

reputation as Rosemary Lane, but it is a squalid place, lined with old

clothes' shops and stalls, and on Sunday mornings the aspect of Rag

Fair, as it is still commonly called, is anything but edifying. A

revised version of this work by Wheatley and T.R. Way, Later Reliques

of Old London (G Bell 1897) includes this 1887 plate of Sharpe's Row, numbers 2, 3, 3½ & 4, in Royal Mint Street. Right

are three other drawings and sketches from the period - 1871 by Charles

James Richardson, 1880 by John Philipps Emslie and 1897 by Robert

Randoll - and a photograph of 1900. The

market continued in Royal Mint Street until 1911, but the area became dominated by railway activity [see below]. Petticoat Lane, of course, is still going strong! At 41 Royal Mint Street stood the warehouse of the United Sponge Company (right in 1971 a few years before demolition). A. Nunes-Vais traded as the United

Sponge Company, importers and dealers in sponges,

at 77 Minories (where Harold May / Marks / Marcuson also traded as the

National Sponge Company), and together with May as importers

and dealers in chamois leathers at

11 The Crescent, Minories. Henry Mayhew had commented, in 1851, this

[sponge selling] is one of the street-trades which has long been in the hands of the

Jews, and, unlike the traffic in pencils, sealing wax, and other

articles of which I have treated, it remains so principally still,

and he lists several dealers, including

Simon Marks, of 10 Middlesex Street. In 1922 Nunes-Vais and May were

among the 'aliens' granted exemption from s7

of the Aliens Restriction (Amendment) Act 1919 and permitted to change their trading names. In 1944 it was

reported that in the long years of its existence the United Sponge

Company has been able to establish extensive business connections in

all countries of the Eastern Mediterranean for the regular supply of

all varieties of sponges. It ceased trading in 1973 (together with

the Universal Sponge Company, of the same address). See here for the Bahamas sponge trade in the 19th century.

At 41 Royal Mint Street stood the warehouse of the United Sponge Company (right in 1971 a few years before demolition). A. Nunes-Vais traded as the United

Sponge Company, importers and dealers in sponges,

at 77 Minories (where Harold May / Marks / Marcuson also traded as the

National Sponge Company), and together with May as importers

and dealers in chamois leathers at

11 The Crescent, Minories. Henry Mayhew had commented, in 1851, this

[sponge selling] is one of the street-trades which has long been in the hands of the

Jews, and, unlike the traffic in pencils, sealing wax, and other

articles of which I have treated, it remains so principally still,

and he lists several dealers, including

Simon Marks, of 10 Middlesex Street. In 1922 Nunes-Vais and May were

among the 'aliens' granted exemption from s7

of the Aliens Restriction (Amendment) Act 1919 and permitted to change their trading names. In 1944 it was

reported that in the long years of its existence the United Sponge

Company has been able to establish extensive business connections in

all countries of the Eastern Mediterranean for the regular supply of

all varieties of sponges. It ceased trading in 1973 (together with

the Universal Sponge Company, of the same address). See here for the Bahamas sponge trade in the 19th century.

The

Royal Mint Street Goods Station [left in 1926] was built on the site previously

occupied by the London & Blackwall Railway Minories station (see here for its history). It

closed in 1949 and Tower Hill DLR station now occupies this site. (The

1973 view, right, shows the railway looking south, with the spur to London Docks

through the Peabody estate still visible before its demolition.)

The

Royal Mint Street Goods Station [left in 1926] was built on the site previously

occupied by the London & Blackwall Railway Minories station (see here for its history). It

closed in 1949 and Tower Hill DLR station now occupies this site. (The

1973 view, right, shows the railway looking south, with the spur to London Docks

through the Peabody estate still visible before its demolition.)

All that is left is the viaduct itself, and on the

corner of Royal Mint Street and [right in 1914] Mansell Street, a hydraulic accumulator

tower [left].

This was built in two stages between 1894 and 1913, and stored

water held under pressure by a weighted piston, providing hydraulic

power to operate turntables and a lift to move wagons on and

off the viaduct. The faded lettering proclaims 'London Midland &

Scottish

Railway City Goods Station and Bonded Stores'. [The third picture on

the left shows a hydraulic accumulator which performed a similar

function at Bishopsgate goods station, where the new Shoreditch High

Street station on the London Overground is now located; see here for an earlier example of hydraulic railway technology.] Also right is

'the Alleyway', on the site of Abel's Buildings [named after its first

ground landlord - also known as White's Buildings], which runs under

the railway between Royal Mint and Chambers Streets, where fly-tipping

and other rubbish accumulates.

All that is left is the viaduct itself, and on the

corner of Royal Mint Street and [right in 1914] Mansell Street, a hydraulic accumulator

tower [left].

This was built in two stages between 1894 and 1913, and stored

water held under pressure by a weighted piston, providing hydraulic

power to operate turntables and a lift to move wagons on and

off the viaduct. The faded lettering proclaims 'London Midland &

Scottish

Railway City Goods Station and Bonded Stores'. [The third picture on

the left shows a hydraulic accumulator which performed a similar

function at Bishopsgate goods station, where the new Shoreditch High

Street station on the London Overground is now located; see here for an earlier example of hydraulic railway technology.] Also right is

'the Alleyway', on the site of Abel's Buildings [named after its first

ground landlord - also known as White's Buildings], which runs under

the railway between Royal Mint and Chambers Streets, where fly-tipping

and other rubbish accumulates.

In

2010 Zog Brownfield Ventures

put forward ambitious plans to develop

this run-down site, with a hotel and community facilities. They argue

that although the accumulator tower is a 'heritage

asset' forming an important part of the historical railway

infrastructure of the area (and still contains the pulleys and other

equipment), it is in a poor state, compromised for many years by its

shabby surroundings [car park 1977, the street in 1980s during demolitions];

that permission for demolition had previously

been granted; and that its loss would be mitigated by the public value

of the

overall development. The application received planning approval in

December 2011. However, another developer has now taken on this site.

In

2010 Zog Brownfield Ventures

put forward ambitious plans to develop

this run-down site, with a hotel and community facilities. They argue

that although the accumulator tower is a 'heritage

asset' forming an important part of the historical railway

infrastructure of the area (and still contains the pulleys and other

equipment), it is in a poor state, compromised for many years by its

shabby surroundings [car park 1977, the street in 1980s during demolitions];

that permission for demolition had previously

been granted; and that its loss would be mitigated by the public value

of the

overall development. The application received planning approval in

December 2011. However, another developer has now taken on this site.

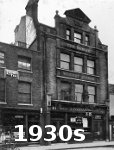

Of the pubs along Rosemary Lane / Royal Mint Street, two buildings remain: Ieft - at no.47, the Crown and Seven Stars (known by this name from c1888, now the Artful Dodger - note the roofline inscription 'Warehouse', and the crest below); and right - the City of Carlisle at 61, rebuilt in the 1860s, but retaining a 1620 terracotta insert, and later known as The Dublin [right, 1930s]. Until its lamented closure in 2013 it was a stylish French restaurant called 'Rosemary Lane'.

Of the pubs along Rosemary Lane / Royal Mint Street, two buildings remain: Ieft - at no.47, the Crown and Seven Stars (known by this name from c1888, now the Artful Dodger - note the roofline inscription 'Warehouse', and the crest below); and right - the City of Carlisle at 61, rebuilt in the 1860s, but retaining a 1620 terracotta insert, and later known as The Dublin [right, 1930s]. Until its lamented closure in 2013 it was a stylish French restaurant called 'Rosemary Lane'.

Back to History page