Backchurch Lane & adjacent streets - which became part of St John's parish

The

lane running south from Commercial Road to Cable Street became the

boundary between the parishes of St Mark Whitechapel and St John the

Evangelist-in-the-East Golding Street. It was densely populated, with a

mix of industrial and residential properties, with dangers to match. At

the end of this page are some contemporary views of the street.

The

lane running south from Commercial Road to Cable Street became the

boundary between the parishes of St Mark Whitechapel and St John the

Evangelist-in-the-East Golding Street. It was densely populated, with a

mix of industrial and residential properties, with dangers to match. At

the end of this page are some contemporary views of the street.

Fires and Explosions

| TERRIFIC BOILER EXPLOSION A fearful explosion occurred on the premises known as the Patent Saw Mills, situated in Back Church Lane, Commercial Road East, one of the most densely crowded districts of London. These premises were divided into several compartments, each fitted up with most costly machinery. A little to the left of these compartments stood the steam-boiler house, in which were deposited two boilers, one about 12-horse and the other between 8 and 9-horse power. The latter of these, which had been in use some time, was at work, and although it was observed to move sluggishly, no danger was apprehended; but between 10 and 11 o'clock in the forenoon a tremendous explosion occurred, which threw the whole neighbourhood into dismay. For the space of half a minute after the explosion happened, nothing but a dense mass of steam and dust could be seen, which ascended so high as to darken the neighbourhood in the immediate vicinity of the premises. The instant the steam and dust in some measure began to clear away, a shower of timber, bricks, and portions of heavy machinery fell. Large piles of wood were seen flying in every direction, which, as they fell upon the house-tops, either forced in the roofs or demolished the back or side walls. At the same time one of the boilers, weighing many tons, was lifted from its bearings, and thrown a long distance from its original position; the other was rent in pieces, and one part, weighing nearly two tons, was forced high into the air, and, after travelling a distance of 100 feet, fell into the back yard, striking in its descent the large premises used as counting-houses and offices, forcing in the windows, and partially destroying the front walls. The crash was tremendous, and at the same instant the school-house in Charles Street was partially blown down; two or three houses adjoining had their roofs and back fronts stove in, and an iron tank, weighing upwards of a ton, was driven by the force of the explosion some distance above the house-tops, and falling upon the roof of the mill, broke through and settled amongst the machinery. The devastation was carried far beyond the property. An aged man passing along the road was struck by a piece of iron, which broke both his legs, and he was obliged to be carried to the London Hospital. A boy passing through Church Lane had his arm fractured by the falling of a large piece of brickwork. Mrs. Young was buried in the ruins, and very severely scalded, and otherwise greatly injured. Mrs. Bailey, residing in the same street, who was looking out of the window at the time of the explosion, received so great a shock that she died on the following morning. |

A note on the

development of firefighting in London A note on the

development of firefighting in LondonThe first commercially-successful fire engine was patented by Richard Newsham in 1725, and many were made in different sizes (Buckingham Palace had once of the largest), and Newsham and Rags (his cousin) was established at 18 New Street, Cloth Fair, West Smithfield. They sold around the country and were even exported to the United States. Around 1750 he was bought out by John and Margaret Bristow (John was a churchwarden at St George-in-the-East in 1784), and production continued in Ratcliff Highway until 1831 - their story is told here. Before 1833 there was no co-ordinated system, and no trained firefighters. The 300 parish engines were under the control of often elderly beadles, and the insurance companies had their own equipment. Saving property rather than people was the priority. The Royal Society for the Protection of Life from Fire, founded in 1828, sought to address this by providing fire ladders in streets, and attending fires to give assistance to individuals at risk.   The

London Fire Brigade (originally the

'London Fire-engine Establishment') was created in 1833 by ten

insurance companies working together, the Sun Fire Office taking the

lead. The first Superintendent was

James Braidwood (1800-61) [right], formerly of Edinburgh, where within weeks of

his appointment at the age of 23 dealt with the Great Fire of

Edinburgh. In his second year in London he faced the major fire at

the

Houses of Parliament. The

London Fire Brigade (originally the

'London Fire-engine Establishment') was created in 1833 by ten

insurance companies working together, the Sun Fire Office taking the

lead. The first Superintendent was

James Braidwood (1800-61) [right], formerly of Edinburgh, where within weeks of

his appointment at the age of 23 dealt with the Great Fire of

Edinburgh. In his second year in London he faced the major fire at

the

Houses of Parliament. He lived 'over the shop' at Watling Street, and

throughout his career saw through many detailed improvements to

structures, apparatus, training and reporting of fires, detailed in his

book Fire Prevention and Fire Extinction

(Bell and Daldy 1866 - cover pictured right). This

was published

posthumously - he died attending the huge fire at Cotton's Wharf,

Tooley Street in 1861. In 1866 the Metropolitan Board of Works assumed

control of the fire service from the insurance companies, fulfilling

one of his hopes; the Metropolitan Fire Brigade became the London Fire

Brigade in 1904. Pictured left is

its first motorised fire engine in 1902.

He lived 'over the shop' at Watling Street, and

throughout his career saw through many detailed improvements to

structures, apparatus, training and reporting of fires, detailed in his

book Fire Prevention and Fire Extinction

(Bell and Daldy 1866 - cover pictured right). This

was published

posthumously - he died attending the huge fire at Cotton's Wharf,

Tooley Street in 1861. In 1866 the Metropolitan Board of Works assumed

control of the fire service from the insurance companies, fulfilling

one of his hopes; the Metropolitan Fire Brigade became the London Fire

Brigade in 1904. Pictured left is

its first motorised fire engine in 1902.

|

Entrepreneurs

Backchurch Lane was also a place where entrepreneurs and men of science

lived and worked. Here are some examples.

In 1839 inventor of the electro-magnet William Sturgeon's Annals of Electricity, Magnetism and Chemistry included this letter from Henley:

A squalid place

Here

are three damning accounts of the area around Backchurch Lane from the

second half of the 19th

century - by which time the district church of St John the Evangelist-in-the-East Grove Street

had been established.

(1) The

first is from The

Christian's Penny

Magazine, and Friend of the People (Congregational Union 1865,

ed J

Campbell), and singles it out as a centre of vice.

(2) The second extract, from James Greenwood Unsentimental Journeys, or

By-ways of the modern Babylon (Ward & Lock 1867) comments on

a particular local trade:

| This

universal fish-frying is the key to another mystery common to the

neighbourhood. In every 'general shop', in every rag and bone shop, in

the high street, and in the hundred courts and filthy alleys that worm

in and out of it, may be seen solid slabs of a tallowy-looking

substance, and marked with a figure 6, 7, or 8, denoting that for as

many pence a pound weight of the suspicious-looking slab may be

obtained. It is bought in considerable quantities by the fish-eaters

for frying purposes, and is by them supposed to be simply and purely

the fat dripping of roast and baked meats, supplied to these shops by

cooks, whose perquisite it is. This, however is a delusion. The

villainous compound is manufactured. There is a 'dripping-maker' near

Seabright-street, Bethnal-green, and another in Backchurch-lane,

Whitechapel, both flourishing men, and the owners of many carts and

sleek cattle. Mutton suet and boiled rice are the chief ingredients

used in the manufacture of the slabs, the gravy of bullocks' kidneys

being stirred into the mess when it is half cold, giving to the whole a

mottled and natural appearance... |

(3) Finally is an article 'The Haunts of the East End Anarchist' from the Evening Standard

of

2 October 1894. It begins with a description of Backchurch Lane and the

small streets to the east of it, before turning to a lurid and

thoroughly racist account of the activities of the radical Jewish

groups that were meeting in the area. See below for pictures of the streets mentioned.

|

Just beyond the Proof-house of the Gunmakers' Company near the Whitechapel end of the Commercial Road, begins a series of narrow streets running at right angles to the main thoroughfare, and cutting Fairclough Street at the further extremity, where the Tilbury and Southend Railway passes through the district [see below]. More or less alike in appearance, these byways, for they are no more, consist entirely of small two-storeyed tenements with an occasional stable or cow-shed to break the monotony, and a sprinkling of little shops devoted to coal and dried fish, stale fruit and potatoes, pickled cucumbers and salt herrings, shrivelled sausages and sour brown bread. There is Backchurch Lane, where the Irish resident still holds his own against the incoming Russo-Jewish settler, and Berner [now Henriques] Street, where the window bills, written in Hebrew characters. inform you that there are 'loshing' or a 'bek-rum' (back room) to let, and thus proclaim the nationality of its denizens. There is Batty Street wholly given over to the foreign tailors, clickers and 'machiners'; Christian Street, long since an appanage of East End Jewry, and Grove [now Golding] Street, where the low-pitched tenements are so far below the pavement level that the passer-by can comfortably shake hands with the residents off the top floor through the bedroom windows. And

intersecting all these are a number of courts, alleys, and passages, so

dark and narrow, so dirty and malodorous, that the purlieus of Seven

Dials and the backways of Clare Market may be called light and airy in

comparison with them. Some are blind, others lead through to the

adjoining thoroughfare. Some branch off to right and left, others

conduct one to open spaces forming irregular quadrangles lined with

houses below the street level, so small and snug that the occupier

standing in his front parlour can open the door, stir the fire, reach

the dustbin outside, or make the bed inside without stirring from the

spot. Courts and alleys, streets and yards, all are densely packed, in

many cases even to the cellars below lighted by small gratings in the

pavement. And the whole district, stretching from Backchurch Lane on

one side to Morgan Street on the other, is the resort and principal

abiding-place of the East End Anarchists. In the side streets and

alleys hereabouts the majority of them live and loaf; within a stone's

throw are their favourites haunts, the coffee-shops they patronise, and

the private gambling-clubs where many spend their evenings, and close

by is their printing press, their temporary club and meeting house, and

even the tavern where their Friday evening discussions take place. If

I dig in the mines of the frozen north,

I'll dig with a will: the ore I bring forth May yet make a knife - a knife for the throat of the Tsar. If I toil in the south, I'll plough and sow Good honest hemp; who knows, I may grow A rope - a rope for the neck of the Tsar. Sarah

Bernhardt might envy the fire and verve with which this recitation is

given by one of the Jewesses, and there can be no possible mistake

about the sentiments of the speaker and her auditory, whatever there

may be about the merits of the verses. And the same fiery stuff, or

fiery stuff of the same description, is being spouted about the same

time at half a dozen other branches of the Anarchist League in the

district between Backchurch Lane and the New Road, that runs up to

Whitechapel. Everything is turned to account, tool for the purposes of

its mischievous propaganda. Why, before the meeting is closed one

member produces and sings an Anarchist version of 'After the Ball',

with a finely-buttered moral drawn from the contrast between the

wealthy dancers inside and the shivering poor outside, winding up with

an Anglo-Yiddish chorus in which all join. |

On 28 June 1885 Miriam Angel was murdered at 16 Batty Street.

She was 21, from Warsaw, and lived with her husband Isaac and was six

months pregnant. When her mother called to visit and got no response,

she sent for the doctor, who found her dead with aquafortis (nitric acid) pouring

from her mouth, wounds to her head and evidence of rape. The attic lodger Israel Lipski (né Lobulsk), a Polish-Jewish 'stick-maker'

(he made umbrella frames) was found in her room, also with acid burns, but survived. He alleged that two fellow-workers, Harry Schmuss and Simon Rosenbloom, had

attacked them, demanding his gold chain, though they claimed to have a good

relationship with him. He had lived in the house for two

years, and was engaged to Kate Lyons, who protested his innocence. A

public subscription was taken up to pay for his defence, but the

barrister engaged, George Geoghegan, had a drink problem so in the

event it was a commercial lawyer who acted for him. The evidence was

confused: a chemist from Bell & Co on the Commercial Road said that

a foreigner had bought acid a few days earlier and he could tell he

was a stick-maker from his clothes, yet it was also said that the

crime was not planned in advance; the rules at that time denied a

closing speech to the defence if the accused spoke for himself or

called witnesses, so Lipski kept silent; and the judge's summing up was

heavily weighted against him.

On 28 June 1885 Miriam Angel was murdered at 16 Batty Street.

She was 21, from Warsaw, and lived with her husband Isaac and was six

months pregnant. When her mother called to visit and got no response,

she sent for the doctor, who found her dead with aquafortis (nitric acid) pouring

from her mouth, wounds to her head and evidence of rape. The attic lodger Israel Lipski (né Lobulsk), a Polish-Jewish 'stick-maker'

(he made umbrella frames) was found in her room, also with acid burns, but survived. He alleged that two fellow-workers, Harry Schmuss and Simon Rosenbloom, had

attacked them, demanding his gold chain, though they claimed to have a good

relationship with him. He had lived in the house for two

years, and was engaged to Kate Lyons, who protested his innocence. A

public subscription was taken up to pay for his defence, but the

barrister engaged, George Geoghegan, had a drink problem so in the

event it was a commercial lawyer who acted for him. The evidence was

confused: a chemist from Bell & Co on the Commercial Road said that

a foreigner had bought acid a few days earlier and he could tell he

was a stick-maker from his clothes, yet it was also said that the

crime was not planned in advance; the rules at that time denied a

closing speech to the defence if the accused spoke for himself or

called witnesses, so Lipski kept silent; and the judge's summing up was

heavily weighted against him.

He was convicted and sentenced to hang;

the night before his execution at Newgate he made a full 'confession'

to the Rev Simeon Singer (a rabbi who at the time of Queen Victoria's

jubilee asserted, of the Jewish population of London, we are Englishmen and and the thoughts and feelings of Englishmen are our thoughts and feelings); but the details of this confession didn't add up. A wave of antisemitism followed - 'Lipski' became a term of abuse.

He was convicted and sentenced to hang;

the night before his execution at Newgate he made a full 'confession'

to the Rev Simeon Singer (a rabbi who at the time of Queen Victoria's

jubilee asserted, of the Jewish population of London, we are Englishmen and and the thoughts and feelings of Englishmen are our thoughts and feelings); but the details of this confession didn't add up. A wave of antisemitism followed - 'Lipski' became a term of abuse.

In December 1911 it was renamed Premierland ('Pree-mier-land') and it

incorporated a boxing ring, where many East End boxers began their

careers, many of them Jewish (among them Ted 'Kid' Lewis at the opening match, and Jack 'Kid' Berg).

In 1924 Victor Berliner [left]

and Manny Lyttlestone presided over its most successful era. A 1920's

boxing boom meant

there were three or four shows a week. The crowds were a mix

of Jewish and Irish immigrants and native cockneys: mostly men who

worked as dockers, barrow boys or street traders at nearby Petticoat

Lane. Some were current or ex-professional boxers, and generally those

who weren't had at least boxed for boys' clubs. As well as Lewis and

Berg, Teddy Baldock, Kid Pattenden, Harry Mason, Nipper

Pat Daly and Dick and Harry Corbett were big stars. Former fighter Jack

Hart was the house referee for much of the period, mostly officiating

from outside the ring. Right is

a 1929 poster and a photo of a 1930 bout, where Whitechapel-born Al

Forman (aka Bert 'Kid' Harris') - who boxed extensively in the USA,

Canada and Australia - defeated Fred Webster of Kentish Town to take

the lightweight championship. Cannily, Forman promoted the fight, and

booked the venue, himself.

In December 1911 it was renamed Premierland ('Pree-mier-land') and it

incorporated a boxing ring, where many East End boxers began their

careers, many of them Jewish (among them Ted 'Kid' Lewis at the opening match, and Jack 'Kid' Berg).

In 1924 Victor Berliner [left]

and Manny Lyttlestone presided over its most successful era. A 1920's

boxing boom meant

there were three or four shows a week. The crowds were a mix

of Jewish and Irish immigrants and native cockneys: mostly men who

worked as dockers, barrow boys or street traders at nearby Petticoat

Lane. Some were current or ex-professional boxers, and generally those

who weren't had at least boxed for boys' clubs. As well as Lewis and

Berg, Teddy Baldock, Kid Pattenden, Harry Mason, Nipper

Pat Daly and Dick and Harry Corbett were big stars. Former fighter Jack

Hart was the house referee for much of the period, mostly officiating

from outside the ring. Right is

a 1929 poster and a photo of a 1930 bout, where Whitechapel-born Al

Forman (aka Bert 'Kid' Harris') - who boxed extensively in the USA,

Canada and Australia - defeated Fred Webster of Kentish Town to take

the lightweight championship. Cannily, Forman promoted the fight, and

booked the venue, himself. By this date, when most boxing venues had become

grander in style and scale, it had become dilapidated, and a High Court case T.M. Fairclough

& Sons v Berliner [1931] 1 Ch 60 determined

that the owners of the property were entitled to relief. (It turned on

technical issues of joint tenancy, under the recent 1925 Law of

Property Act, and so was frequently cited in the following years.) In due course it

became a garage for Fairclough's motor vehicles - see here

for the story of this firm: 75 years earlier Thomas Morrison Fairclough

has been churchwarden of the parish. In the 1960s, a New Premierland

boxing

venue was based at Poplar Baths; the old building later became a

warehouse [right in 1980s].

By this date, when most boxing venues had become

grander in style and scale, it had become dilapidated, and a High Court case T.M. Fairclough

& Sons v Berliner [1931] 1 Ch 60 determined

that the owners of the property were entitled to relief. (It turned on

technical issues of joint tenancy, under the recent 1925 Law of

Property Act, and so was frequently cited in the following years.) In due course it

became a garage for Fairclough's motor vehicles - see here

for the story of this firm: 75 years earlier Thomas Morrison Fairclough

has been churchwarden of the parish. In the 1960s, a New Premierland

boxing

venue was based at Poplar Baths; the old building later became a

warehouse [right in 1980s]. Charles Kinloch & Co, Backchurch Lane

Charles Kinloch & Co, Backchurch Lane Charles Kinloch (1828-97) was the youngest child of Captain Charles

Kinloch of Gourdie (who had served with the 52nd Regiment in the

Peninsular War); he attended Edinburgh Academy and the University of

Bonn. He married Harriet Kingston, relative of a well-known children's

author. He established a firm of wine and spirits dealers in 1861; the

following year they were advertising at the International Exhibition [left], with premises near Mansion House in the City [right].

Charles Kinloch (1828-97) was the youngest child of Captain Charles

Kinloch of Gourdie (who had served with the 52nd Regiment in the

Peninsular War); he attended Edinburgh Academy and the University of

Bonn. He married Harriet Kingston, relative of a well-known children's

author. He established a firm of wine and spirits dealers in 1861; the

following year they were advertising at the International Exhibition [left], with premises near Mansion House in the City [right].

In 1884, with premises at Backchurch Lane and also at 3 Queen Victoria Street, Thomas Mackay

(1849-1912) left the partnership with Kinloch and George Scott. He was a cousin of Kinloch's father

who was keen to be involved in social work but accepted advice to start

in business. He was an unlikely city merchant, but made a substantial

fortune, and retired to write on social questions and to work with the Charity Organisation Society.

Henceforth Scott was the managing director until his death in

1893; he had homes at Eagle Villa, Queen's Road in Peckham and at

Scott-Rea, Tully Powrie, Perthshire. Two years earlier the firm had been incorporated as Charles

Kinloch & Co Ltd, wine, whsky and brandy merchants. In 1888 they advertised themselves as sole UK consignees of Bouvet-Ladubay,

St. Hilaire-St. Florent & Epernay, growers and shippers of extra

royal, sec and brut. But over the years perhaps their most distinctive

product was dark Jamaica rum, which they sold as 'Liquid Sunshine' [labels left].

In 1884, with premises at Backchurch Lane and also at 3 Queen Victoria Street, Thomas Mackay

(1849-1912) left the partnership with Kinloch and George Scott. He was a cousin of Kinloch's father

who was keen to be involved in social work but accepted advice to start

in business. He was an unlikely city merchant, but made a substantial

fortune, and retired to write on social questions and to work with the Charity Organisation Society.

Henceforth Scott was the managing director until his death in

1893; he had homes at Eagle Villa, Queen's Road in Peckham and at

Scott-Rea, Tully Powrie, Perthshire. Two years earlier the firm had been incorporated as Charles

Kinloch & Co Ltd, wine, whsky and brandy merchants. In 1888 they advertised themselves as sole UK consignees of Bouvet-Ladubay,

St. Hilaire-St. Florent & Epernay, growers and shippers of extra

royal, sec and brut. But over the years perhaps their most distinctive

product was dark Jamaica rum, which they sold as 'Liquid Sunshine' [labels left].

In 1894-5 a fine new warehouse by Hyman Henry Collins was completed. Note

the details, including the carved in and out signs, set into coloured engineering bricks. The firm continued to expand, and pursue creditors - including in 1908

Max Sichel, a bankrupt wine and spirit merchant of Wolverhampton and in

1924 the owners of the unlikely-named Riviera Hotel, Maidenhead.

In 1894-5 a fine new warehouse by Hyman Henry Collins was completed. Note

the details, including the carved in and out signs, set into coloured engineering bricks. The firm continued to expand, and pursue creditors - including in 1908

Max Sichel, a bankrupt wine and spirit merchant of Wolverhampton and in

1924 the owners of the unlikely-named Riviera Hotel, Maidenhead. In

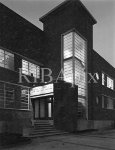

1937 they opened a new factory at Queensbury Road, Wembley [later Park

Royal] in 'Modern Movement' style by E.E. Williams & E.G.

Winbourne [left - RIBA image]. By 1950 they were supplying 4,000 lines of wines and spirits

(including Southern Comfort) nationwide, and owned or part-owned four

other companies. Even after they themselves were acquired by Courage

and Barclay in 1957, this process continued, as they bought up five

other firms as non-trading subsidiaries. In 1961, their centenary year,

they produced a 42-page pamphlet The Taste of Kinloch, a handbook of wines and spirits based on the experience of 100 years

(written by Pamela Joan Vandyke Price, published G. Street). The

company was formally dissolved in 2008; its residual trading address is

now Mercer and Hole, International Press Centre, Shoe Lane EC4.

In

1937 they opened a new factory at Queensbury Road, Wembley [later Park

Royal] in 'Modern Movement' style by E.E. Williams & E.G.

Winbourne [left - RIBA image]. By 1950 they were supplying 4,000 lines of wines and spirits

(including Southern Comfort) nationwide, and owned or part-owned four

other companies. Even after they themselves were acquired by Courage

and Barclay in 1957, this process continued, as they bought up five

other firms as non-trading subsidiaries. In 1961, their centenary year,

they produced a 42-page pamphlet The Taste of Kinloch, a handbook of wines and spirits based on the experience of 100 years

(written by Pamela Joan Vandyke Price, published G. Street). The

company was formally dissolved in 2008; its residual trading address is

now Mercer and Hole, International Press Centre, Shoe Lane EC4.

In 1969 Robert Rayleigh & Co, of the Commercial Road, acquired 107

Backchurch Lane and 26/42 Gowers Walk for clients - 74,000 sq ft with

footage of 150ft to Backchurch Lane. Collins' warehouse (with glazed

rooftop extensions) eventually became apartments in 1999.

In 1969 Robert Rayleigh & Co, of the Commercial Road, acquired 107

Backchurch Lane and 26/42 Gowers Walk for clients - 74,000 sq ft with

footage of 150ft to Backchurch Lane. Collins' warehouse (with glazed

rooftop extensions) eventually became apartments in 1999.

In 1812 Henry

Potter set up as a dealer in leeches, and seedsman and herbalist, in

Fleet Market, Farringdon Street, retiring in 1846. The firm of Potter

and Clarke became leading wholesale suppliers of herbs for medicinal

uses, and from 1907 (or earlier) produced their influential [New]

Cyclopædia of Botanical Drugs and Preparations,

which went through many

editions: it was still being published in the 1970s (by Health Science

Press, Devon) when use of herbs had disappeared from medical practice.

From the turn of the century they also issued their own trade paper, Potter's Bulletin. They

were under growing pressure from registered medical practitioners, who

claimed exclusive use of the title 'doctor', and reported prosecutions

of herbalists for treating diphtheria, for example. A Commission on the

far-reaching provisions of the 1858 Medical Act concluded that it was undesirable to attempt to prevent unregistered persons from practising. But the struggles continued. In

1947 Potter & Clarke brought a test action against the Pharmaceutical Society of

Great Britain over the definition of 'substances recommended as a

medicine' and 'proprietory designation' under sections 11 and 12 of the

Pharmacy and Medicines Act 1941. (See here and here for much earlier

local examples of spats over an issue which has many contemporary resonances, and here for

an example of a genuine local quack!)

In 1812 Henry

Potter set up as a dealer in leeches, and seedsman and herbalist, in

Fleet Market, Farringdon Street, retiring in 1846. The firm of Potter

and Clarke became leading wholesale suppliers of herbs for medicinal

uses, and from 1907 (or earlier) produced their influential [New]

Cyclopædia of Botanical Drugs and Preparations,

which went through many

editions: it was still being published in the 1970s (by Health Science

Press, Devon) when use of herbs had disappeared from medical practice.

From the turn of the century they also issued their own trade paper, Potter's Bulletin. They

were under growing pressure from registered medical practitioners, who

claimed exclusive use of the title 'doctor', and reported prosecutions

of herbalists for treating diphtheria, for example. A Commission on the

far-reaching provisions of the 1858 Medical Act concluded that it was undesirable to attempt to prevent unregistered persons from practising. But the struggles continued. In

1947 Potter & Clarke brought a test action against the Pharmaceutical Society of

Great Britain over the definition of 'substances recommended as a

medicine' and 'proprietory designation' under sections 11 and 12 of the

Pharmacy and Medicines Act 1941. (See here and here for much earlier

local examples of spats over an issue which has many contemporary resonances, and here for

an example of a genuine local quack!)

In 1925 they built a new drug grinding plant on Fairclough Street (on

the site of Oates Drug Mills) - adjacent to Victoria Mills on Berner

[Henriques] Street, designed in 1923 by Wheat and Luker, and now

apartments [right]. The Industrial Chemist of 1932 (vol 8, page 9) reported this factory is an entirely self-contained

one and has its own water supply from two artesian wells, one of

which is at present in operation and giving 4,500 gallons per hour,

which is automatically pumped to tanks on the roof. Left is a new gate to Victora Yard, and the factory, now apartments, adjacent to two remaining 19th century buildings (nos. 8 & 10).

In 1925 they built a new drug grinding plant on Fairclough Street (on

the site of Oates Drug Mills) - adjacent to Victoria Mills on Berner

[Henriques] Street, designed in 1923 by Wheat and Luker, and now

apartments [right]. The Industrial Chemist of 1932 (vol 8, page 9) reported this factory is an entirely self-contained

one and has its own water supply from two artesian wells, one of

which is at present in operation and giving 4,500 gallons per hour,

which is automatically pumped to tanks on the roof. Left is a new gate to Victora Yard, and the factory, now apartments, adjacent to two remaining 19th century buildings (nos. 8 & 10). |

West Side |

East Side |

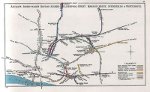

Pinchin

Street [see below for the origin of the name] runs alongside the railway viadact which led north from the main

line to the London, Tilbury & Southend Railway's goods depot on

Commercial Street, opened in 1886, one of several short spurs to goods

stations in the area [see map, right]. At

the same time, a hydraulic pumping station to power the equipment

shifting wagons to and from street level was built in nearby Hooper Street -

see here for details.

The street's main claim to fame is as a 'Ripper site'. On 10 September

1889 a headless female torso, possibly that of Linda Hart, a local

prostitute, was found under one of the railway arches - many sites

refer!

Pinchin

Street [see below for the origin of the name] runs alongside the railway viadact which led north from the main

line to the London, Tilbury & Southend Railway's goods depot on

Commercial Street, opened in 1886, one of several short spurs to goods

stations in the area [see map, right]. At

the same time, a hydraulic pumping station to power the equipment

shifting wagons to and from street level was built in nearby Hooper Street -

see here for details.

The street's main claim to fame is as a 'Ripper site'. On 10 September

1889 a headless female torso, possibly that of Linda Hart, a local

prostitute, was found under one of the railway arches - many sites

refer!

The goods depot closed in 1967 and most of the viaduct was demolished, leaving a short spur which campaigners have fought to save as a nature space [pictured left],

a space housing local businesses in the arches, and to prevent further

local overcrowding. Here are various views of the street, including

arch no.15 some years ago where a 'traditional' craft was practised. Among current businesses 'under the arches' is the Hand & Eye Press, started in 1985 at no.6 and using traditional letterpress technology; far right shows the space typically in one of the units.

The goods depot closed in 1967 and most of the viaduct was demolished, leaving a short spur which campaigners have fought to save as a nature space [pictured left],

a space housing local businesses in the arches, and to prevent further

local overcrowding. Here are various views of the street, including

arch no.15 some years ago where a 'traditional' craft was practised. Among current businesses 'under the arches' is the Hand & Eye Press, started in 1985 at no.6 and using traditional letterpress technology; far right shows the space typically in one of the units.

At the eastern end of Pinchin Street, beyond the arches, are two interesting buildings - one old, one new. At no.2 [left, 3 views] on the corner with Christian Street is the Pinchin Street Studios and Group Practice, constructed in 2007 by Urban Space Management Ltd

from 35 shipping containers to provide ten units - a doctors' surgery

on the first two floors, office space on the next three, and with a

roof garden and plant nursery with spectacular views. Next door [right, two views], at no.4

is the former warehouse (now flats) of Pinchin and Johnson,

a paint company selling oils and turpentines started in 1834 in

Silvertown. They opened branches around the world, and were listed on

the original FT 30 index. In 1960 it was bought by Courtaulds who

merged it with International Paints in 1968. ('L' prefix codes for

nitro-cellulose car paints refer to their products.) Opposite is a mosque, the East London Markazi Masjid.

At the eastern end of Pinchin Street, beyond the arches, are two interesting buildings - one old, one new. At no.2 [left, 3 views] on the corner with Christian Street is the Pinchin Street Studios and Group Practice, constructed in 2007 by Urban Space Management Ltd

from 35 shipping containers to provide ten units - a doctors' surgery

on the first two floors, office space on the next three, and with a

roof garden and plant nursery with spectacular views. Next door [right, two views], at no.4

is the former warehouse (now flats) of Pinchin and Johnson,

a paint company selling oils and turpentines started in 1834 in

Silvertown. They opened branches around the world, and were listed on

the original FT 30 index. In 1960 it was bought by Courtaulds who

merged it with International Paints in 1968. ('L' prefix codes for

nitro-cellulose car paints refer to their products.) Opposite is a mosque, the East London Markazi Masjid.

1909:

1909:

1938 - three street corners:

1938 - three street corners:

Backchurch Lane today:

Backchurch Lane today:

Other streets:

Other streets:

- Boyd Street

- Boyd Street Back to History page | Back to St John the Evangelist-in-the-East