This

proprietary chapel was established, only a few

hundred yards north from the parish church on Cannon Street Road

[formerly New Road],

between what are now Chapman and Bigland Streets (Chapel Street

lay between them), for reasons not entirely clear, though presumably

related initially to work with seafarers in the various institutions

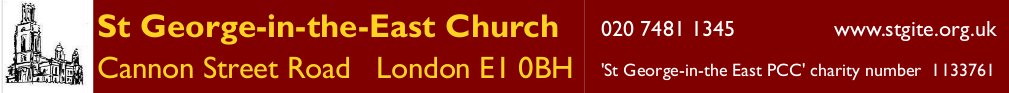

decribed below. The premises were previously a Congregational chapel. Horwood's map of 1792/9 [left] shows its location (in red), with the burial yard behind; it is still shown on a street map of 1875 [right], though having become a Methodist chapel when the Anglicans moved out, it was demolished around this time.

Sailors' Rest Asylum / Shipwrecked & Distressed Sailors' Asylum

| Some years since, I had formed the Sailors' Rest Asylum, and provided for shipwrecked and distressed sailors lodging and food, until they could get ships. At first we had an Asylum House, in Wellclose-square ...The house became too small, and I then sought out, and engaged a large range of premises in Cannon-street-road, having a wide entrance and two folding gates. Here was a dwelling-house for the manager, and the premises being in a ruinous state, I had an extensive place below fitted out with tables, forms, and stoves, as the Sailors' Mess, and a large floored place above, as the Sailors' dormitory for clean straw, and an old sail as a covering. The Sailors' Mess was the chapel every night and morning. Opposite to this I had another range of premises, as the cook-house and kitchen, and at the expense of £200 had these fitted up, also, for sailors. All this I carried on and had supported, and the greatest good was done with hundreds of poor destitute or cast-away sailors, who went out, or came from all parts of the world. A company of dissenting ministers and laymen examined the whole of the Sailors' Rest Asylum in 1831 ... and all the ministers and laymen pronounced it the most important institution, and worthy of all possible support. When the twenty four ministers, who had engaged to take the whole of our establishment, withdrew from it, without any justifiable cause, I found we could no longer support this cause in Cannon-street-road ... [and offered to transfer it to Dr Fletcher of Stepney] ... but to my great surprise and grief he refused it altogether, in consequence of other ministers withdrawing, so that I was obliged to transfer it to the Rev. Mr. B [Thomas Boddington], a clergyman of the Church of England, who took it in connection with Trinity Episcopal Church, in Cannon-street-road; and after two or three years he transferred it to a captain of the navy, who obtained the Bishop of Llandaff's patronage, and Admiral Sir Edward Codrington, as president, with some, also, of the lords of the Admiralty. Sir Edward made his experience of this institution the principal ground of all his evidence before the Shipwreck-committee of the House of Commons. At length the whole failed, and was broken up and destroyed; so that now there is only one Sailors' Asylum, in Well-street, where no dissenting minister would be allowed to preach. The nightly shelter for the houseless, by the London Docks, housed about seventy destitute sailors of a night, last winter; but no non-conformist minister is allowed there: but had Dr. Fletcher kindly taken the Sailors' Rest Asylum, and the dissenting and methodist ministers united with him, they might have had all the money the Blackwall Railway gave for pulling down all the premises and making a new road directly through what was our Sailors' Rest Asylum; and thus all the evangelical ministers could have had access every night to preach to sailors, who would be compelled to be present. One hundred every night, who would be the greatest curse or the greatest blessing to all parts of the world, as they obtained ships for foreign voyages! |

|

THE SAILORS' ORPHAN GIRLS' ASYLUM June 1848

The Sailors' Orphan Girls Episcopal School and Asylum receives within its walls twenty orphan daughters of British seamen, whether belonging to the navy or merchant service, between the ages of 3 and 15, whom it boards, clothes, educates, and aims to set forward in life by placing them out as servants in respectable families. It also extends a measure of the same advantages to about twenty others, allowed to attend daily from the neighbourhood. More than 600 such children have during the last 18 years, been thus rescued from the worst miseries of the orphan's lot; and much of lasting benefit, as well as present relief, has thus been ministered to the poor and destitute. The charity has not been without influential patronage; headed by Her Royal Highness the Duchess of Kent, and the Right Honourable Lord Byron. But we all know it is from the many in the middle ranks of life, rather than the few in the higher, that the practical support of our public institutions is reasonably expected. Thank God, in our land, and in our day, we are not wont to look to these in vain, when the claims of any such cause have been once satisfactorily established. Yet the vast variety of appeals presented to all who are able and inclined to attend to them, and the round of busy engagements in which all but positive idlers seem ever involved, are frequent hindrances to those being heard, which need only a hearing to ensure them a kind and effectual response. Added to this, with regard to the charity in question, the wretched locality in which it unfortunately stands, amidst the dense population of our sea-faring men and their families, has always been an obstacle to its being either frequently inspected by visitors, or very regularly superintended by an efficient Lady's [sic] Committee of management. It is therefore [a] matter of more concern than surprise, that it has thus long remained comparatively little known, and in consequence, most inadequately supported. In fact the efforts and liberality of a few friends, who have tested and proved its value, aided by the faithful and unwearied exertions of its School-mistress, have alone prevented its falling to the ground: and these have failed to keep it free from the incumbrance of a debt, which unceasingly damps its energies, and cripples its operations. Urgent and affecting applications for admittance, the Committee are reluctantly compelled to turn a deaf ear to, in the present state of their finances: and either the removal to more commodious premises, or the much needed repair and improvement of those they at present rent, they likewise feel it their painful duty to defer. Being without endowment, or any other resources than the fluctuating list of annual subscribers and benefactors, aided by an occasional sermon, and from time to time a sale of such useful and ornamental articles as a few kind and warm friends are ready to supply, the Commit te find their charge,. however interesting, one of frequent anxiety and embarrassment. Still,. however, the Institution pursues its quiet unobtrusive course of usefulness, relieving many a widowed heart of a portion of its burden, saving many a helpless orphan child from want and ruin, and sending forth, year by year, into that important, though humble, class of the community, our household servants, those whom it has trained in the principles and habits that will best prepare them to learn and labour truly to get their own living, and to do their duty in that state of life "to which it has pleased God to call them". Wives, mothers, sisters, daughters, of British sailors, placed happily out of reach of the privations and perils which but for such a shelter, must overwhelm this orphan band: husbands, fathers, brothers, personally familiar with the casualties of a profession, that is daily making the children fatherless, and the wives widows in the midst of us: all who recognize the special claims of British seamen on their fellow-countrymen and fellow countrywomen,— such will surely need but to be informed of the existence and the difficulties of an institution like this; and they will promptly stretch forth to it their helping hand, if only in gratitude to a kind Providence, for their own happier lot. But twenty of these children, as wholly dependent, and but forty, as partially so, do the Committee venture to present for support, to the thousands around who have more than heart could wish. Shall this handful then plead in vain? No! rather by "delivering the fatherless, and her that had none to help her", may the rich "blessing of her that was ready to perish come upon" every kind reader of this appeal on their behalf. Subscriptions and

Donations are thankfully received by Messrs. Barclay, Bevan, Tritton,

& Co., Lombard Street; by Mr. Nisbet, 21, Berners Street; Messrs.

Seeley, Fleet Street; Messrs. Hatchard, Piccadilly; at the Office of

the Naval and Military Bible Society, 32, Sackville Street,

Piccadilly; at the Sailors Home Office, 23, Well Street, London

Docks; by the Honorary Secretary, the Rev. J. Lyons, A.M., St. Mark's

Parsonage, Whitechapel; or by Mrs. Largent, at the Sailors' Orphan

Girls' Episcopal School, 29, Cannon Street Road, St. George's East,

London, where visitors also are respectfully invited. |

| .....rescuing

from depravity, and the greatest state of indigency, children

of British seamen who have perished in the their country, and to

maintain clothe, educate, and suitably prepare them as servants &c. Every person

subscribing one guinea per annum, or ten guineas as a life

subscription, is entitled to recommend children to the notice of the

committee, who, as the funds may admit of it, add to the objects of

the charity. No child is admitted without three such recommendations,

except on the payment of 70 guineas, when the child is at once

admitted.

President, Sir James Hillyar. — Treasurer, John Cook. Esq., Goodman's-yard.— Secretaries G. Gull, Esq., 68, Old Broad-street; Rev. C.J. Hyatt, 14, Hardwick-place, Commercial-road. — [Collector], Mr. C. Gordelier, 92, Fenchurch-street. — [Bankers], Messrs. Robarts, Curtis, and Co., Lombard-street. — [Superintendent], Mrs. Orton, at the Asylum. |

Nearby was the first home of the Merchant Seamen's Orphan Asylum, set up following a public meeting in October 1827 by Bo'sun Smith with Phillips and Thompson in connection with the Port of London and Bethel Union Society, to

provide a home for the destitute off-spring of British merchant seaman

with a view to assisting and benefiting them when disease, accident or

calamity at sea deprived them of the chief support. Initially it

housed five boys in the care of Mr & Mrs Fisher at 3 & 4

Clark's Terrace, Cannon Street Road; two years later there were eleven,

plus five girls at 11 St George's Place. In 1833, after Smith separated

from his associates, it became a Society [left are

its admission rules of that year]; illness and constant expense

for 'changes of air' dictated a move the following year to New Grove,

an old mansion in Bow Road, which in 1852 was maintaining 84 boys and

40 girls, with an average income of £2,500 (later rising to £3,113), all from

voluntary contributions except about £180 from dividends.

Nearby was the first home of the Merchant Seamen's Orphan Asylum, set up following a public meeting in October 1827 by Bo'sun Smith with Phillips and Thompson in connection with the Port of London and Bethel Union Society, to

provide a home for the destitute off-spring of British merchant seaman

with a view to assisting and benefiting them when disease, accident or

calamity at sea deprived them of the chief support. Initially it

housed five boys in the care of Mr & Mrs Fisher at 3 & 4

Clark's Terrace, Cannon Street Road; two years later there were eleven,

plus five girls at 11 St George's Place. In 1833, after Smith separated

from his associates, it became a Society [left are

its admission rules of that year]; illness and constant expense

for 'changes of air' dictated a move the following year to New Grove,

an old mansion in Bow Road, which in 1852 was maintaining 84 boys and

40 girls, with an average income of £2,500 (later rising to £3,113), all from

voluntary contributions except about £180 from dividends.  The

next move came in 1862, to new premises at Hermon Hill, Snaresbrook, on

a 7-acre Wanstead Forest site purchased from Lord Mornington (a

relative of the Duke of Wellington), designed in elaborate

pseudo-Venetian style by George Somers Clarke; the Prince Consort laid

the foundation stone and it was opened Lord John Russell. It housed 130

boys and 75 girls, expanding by 1883 to 270 children; the chapel seated

300 plus staff. It moved again in 1919/20, as a result of World War I,

and nuns of the Convent of the Good Shepherd took over the site; Essex

County Council bought it as hospital in 1938 and ten years later, under

the NHS, it became Wanstead Hospital, with 188 beds. (The exterior

became 'St Swithin's' for filming Doctor in the House.)

The maternity unit closed in 1975, with full closure in 1986 because of

poor cleanliness and high infant mortality, plans for a new hospital on

the site having failed. Most of the site was converted into residential

accommodation, as Clock Court, in 2006, but the grade II-listed chapel

became Sukkat Shalom Reform Synagogue - their website gives a detailed description of the building.

The

next move came in 1862, to new premises at Hermon Hill, Snaresbrook, on

a 7-acre Wanstead Forest site purchased from Lord Mornington (a

relative of the Duke of Wellington), designed in elaborate

pseudo-Venetian style by George Somers Clarke; the Prince Consort laid

the foundation stone and it was opened Lord John Russell. It housed 130

boys and 75 girls, expanding by 1883 to 270 children; the chapel seated

300 plus staff. It moved again in 1919/20, as a result of World War I,

and nuns of the Convent of the Good Shepherd took over the site; Essex

County Council bought it as hospital in 1938 and ten years later, under

the NHS, it became Wanstead Hospital, with 188 beds. (The exterior

became 'St Swithin's' for filming Doctor in the House.)

The maternity unit closed in 1975, with full closure in 1986 because of

poor cleanliness and high infant mortality, plans for a new hospital on

the site having failed. Most of the site was converted into residential

accommodation, as Clock Court, in 2006, but the grade II-listed chapel

became Sukkat Shalom Reform Synagogue - their website gives a detailed description of the building.  The

new home of what from 1902 had been the Royal Merchant Seamen's

Orphanage was Bearwood, in Godalming, a vast mansion built between

1865-74 by the son of the owner of The Times; its opening in 1922 is

described here.

In 1935 it was renamed the Royal Merchant Navy School (1935) /

Foundation (1980), but since 1961 has been Bearwood College, an

independent school, now co-educational, retaining its Christian

character.

The

new home of what from 1902 had been the Royal Merchant Seamen's

Orphanage was Bearwood, in Godalming, a vast mansion built between

1865-74 by the son of the owner of The Times; its opening in 1922 is

described here.

In 1935 it was renamed the Royal Merchant Navy School (1935) /

Foundation (1980), but since 1961 has been Bearwood College, an

independent school, now co-educational, retaining its Christian

character. In

1836 he became the chaplain of Giltspur Street Compter [right], a prison

built opposite Newgate (to designs by George Dance the Younger) in 1791

to replace two small City gaols, mainly to house debtors but also

felons and other offenders, and vagrants and 'night-charges'; it was

demolished in 1855. As the third annual report of the

Prison Inspectors

(Supplement, p31ff) explains, Boddington had actually read the daily

prayers with a

biblical exposition on a voluntary basis for some time prior to his

formal appointment, as his predecessor was too ill to perform his

duties, which had in any case for many years been undertaken on his

behalf by the 'Taskmaster'. His salary there was £200 a year. He resigned in

1842, after a trial at the Middlesex Sessions when he and Matilda

Tippett[s], a former prisoner at the Compter with whom

he had formed a relationship (they may have married), were accused - though acquitted - of a murderous

assault on Matilda's husband Frederick Penn Tippett: here

are two press accounts of the murky story. The Accident Relief Society

(for Affording Assistance to the Families of the Suffering Poor in

Cases of Sudden Injury - founded in 1838) was at pains to make clear that he had broken

his links with them two years previously.

In

1836 he became the chaplain of Giltspur Street Compter [right], a prison

built opposite Newgate (to designs by George Dance the Younger) in 1791

to replace two small City gaols, mainly to house debtors but also

felons and other offenders, and vagrants and 'night-charges'; it was

demolished in 1855. As the third annual report of the

Prison Inspectors

(Supplement, p31ff) explains, Boddington had actually read the daily

prayers with a

biblical exposition on a voluntary basis for some time prior to his

formal appointment, as his predecessor was too ill to perform his

duties, which had in any case for many years been undertaken on his

behalf by the 'Taskmaster'. His salary there was £200 a year. He resigned in

1842, after a trial at the Middlesex Sessions when he and Matilda

Tippett[s], a former prisoner at the Compter with whom

he had formed a relationship (they may have married), were accused - though acquitted - of a murderous

assault on Matilda's husband Frederick Penn Tippett: here

are two press accounts of the murky story. The Accident Relief Society

(for Affording Assistance to the Families of the Suffering Poor in

Cases of Sudden Injury - founded in 1838) was at pains to make clear that he had broken

his links with them two years previously.

The

chapel also had

a burial ground, though it was not managed by the church. Here, from the London Shipping Gazette of 5 September 1837, is a descrption of the burial of a young apprentice:

| [It will be recollected that in addition to the boy Matthews and a

Maltese servant, who were killed by the explosion of gunpowder, in a

powder-boat alongside the Maltese brig Guiseppe, a fortnight ago,

several others were seriously injured, one of whom, the mate of the

brig (who was in the cabin at the time the gunpowder ignited), was

wounded, and his face severely cut by the broken glass of the cabin

skylight falling upon him. He remained in the Dreadnought hospital ship

from the Wednesday night, when the explosion took place, until the

following Sunday, when, feeling himself quite well, and suffering but

little or no inconvenience from the wounds, he took his departure. He

was previously a man of sober and steady habits, but, whether the

fright unsettled his mind or not, he aftewards took to drinking, and

for several days after he left the hospital ship he was in a state of

intoxication. The immoderate quantity of ardent spirits drunk by the

mate brought on an attack of erysipelas, from the effects of which he

died on Sunday afternoon.] About the time the unfortunate man breathed

his last, the funeral procession of the apprentice Matthews passed

through the streets of St. George’s in the East, within a few yards of

the mate’s abode. Eight lads, watermen’s apprentices, preceded the

coffin, containing the remains of the poor boy. They were attired in

blue jackets, white trousers, and white gloves, with black crape round

their arms. The parents and relatives of the deceased followed the

coffin, which was covered with a pall, and supported on the shoulders

of four men. In this manner the mournful procession moved towards the

burial-ground of Trinity Episcopal Chapel, in Cannon-street-road,

followed by an immense concourse of spectators.

[His master, Mr. Corsan,

the powder-lighterman, is still confined to his room; he is gradually

recovering, but it will be very long before he is enabled to leave his

home. The poor boy who belonged to the brig, and who was so frightfully

mutilated, still remains on board the Dreadnought hospital-ship in a

melancholy state of suffering, and, what is more painful, his reason is

affected. He is receiving every attention which skill and humanity can

suggest on board the Dreadnought. The brig which was shattered by the

gunpowder has been lifted and taken further in shore. In a day or two,

it is expected that she will be sufficiently patched up to be towed

into dock for repairs.] |

Insanitary

and over-full burial grounds in London had become a major problem; as G.A.

Walker reported in Gatherings

from Graveyards in 1839,

| The burying ground at the back of this chapel is large, and very much crowded. The fees are low; many of the Irish are buried here, and bodies are brought from very distant parishes; many of the grave stones have given way. There is a schoolroom for children at one end of the ground, built over a shed, in which are deposited pieces of broken-up coffin wood, tools, &c. |

and this was one of the many sites mentioned by Walker in evidence to a House of Commons Select Committee in 1842, in connection with A Bill for the Improvement of Health in Towns, by removing the Interment of the Dead from their Precincts.

In 1839 The Times

reported controversy over a lascar burial in this

ground, from their barracks in Cannon Street Road; it was observed by

'several thousand' people as an exotic

curiosity. An official of the East India Company had leased space,

and allowed Catholics, Dissenters and lascars to bury their dead there,

for a fee of 7 shillings. Dr Farington, the Rector of St George's,

protested that those who swarm in

the neighbourhood [he meant Dissenters and poor Irish papists as

well as lascars] had a rooted

aversion to the settled order of things both in church and state.

This was typical of the growing anti-Asian prejudice - see Michael

Fisher Counterflows

to Colonialism (2006) chapter 4. Here

are accounts of how Lascars were perceived, from 1805, 1823 and

1839.

In 1839 The Times

reported controversy over a lascar burial in this

ground, from their barracks in Cannon Street Road; it was observed by

'several thousand' people as an exotic

curiosity. An official of the East India Company had leased space,

and allowed Catholics, Dissenters and lascars to bury their dead there,

for a fee of 7 shillings. Dr Farington, the Rector of St George's,

protested that those who swarm in

the neighbourhood [he meant Dissenters and poor Irish papists as

well as lascars] had a rooted

aversion to the settled order of things both in church and state.

This was typical of the growing anti-Asian prejudice - see Michael

Fisher Counterflows

to Colonialism (2006) chapter 4. Here

are accounts of how Lascars were perceived, from 1805, 1823 and

1839.

The London Morning Post of 6 October 1846 reported:

| THAMES — Private Burial Grounds —Yesterday, Mr Rayner, Chairman of the

Board of Guardians of St. George-in-the-East, accompanied by Mr. George

Findlay and Mr. Staples, also guardians, waited on Mr. Ballantine [the stipendiary magistrate of Thames Olice Court], for

the purpose of calling his attention to the over-crowded state of a

burial ground in Cannon-street-road, in the rear of Trinity Episcopal

Chapel, with which edifice, however, the cemetery has no connection.

Mr. Findlay said he was constable of the parish, and he was requested,

in his official capacity, to bring the disgraceful practices carried on

in the burial ground before the notice of the magistrate. The burial

ground, which was of small extent, was over-crowded with human remains.

For some time past a most disgusting and reprehensible practice had

been adopted. The coffins and bodies had been taken out of the graves,

which ought not to have been disturbed, and after the coffins were

broken up, large holes were prepared, into which human remains were

thrown in a heap. Pieces of coffins were often seen about the ground,

with pieces of decomposed flesh and hair adhering to them. The

parishioners were most anxious to prevent any more interments in the

burial ground to abate the nuisance ... |

Mr Ballantine regretted that he could not intervene, despite the noxious effluvium, and

the practice of covering over new graves to give the appearance that

they were of long standing, but he encouraged them to believe that

change was on the way, which indeed was the case.

The later use of this site is described below.

Protestant Association

For part of its brief history, the chapel

was associated with

the Protestant Association,

whose journal The

Penny Protestant Operative reports

various meetings of the local branch, the Tower Hamlets Operative

Protestant Association, in the Cannon Street Road schoolroom and

elsewhere in the borough. For example, in 1840 the

Revd J.

Cotter (from Ireland) delivered a lecture here on

the state of Romanism in Ireland, and the pleasing circumstances

connected with the numerous converts from Popery at Dingle and

Ventry, and exhibited specimens of indulgences and beads. The room

was crowded, and two or three hundred persons were unable to obtain

admission. A collection of £4 10s was taken for a school in Dingle. Monthly meetings of the association's Mutual Instruction Class were held in the schoolroom. As the following shows, several of the ministers of the chapel were active supporters. See here

for another Irish clergyman's involvement with the meetings of the

Association, and his later links with St Matthew Pell Street: in October 1841 he was a speaker at a

meeting of the City of London Tradesmen and Operative Protestant

Association held in the George Hall, Aldermanbury, chaired by James

Harris [see below]: the St James Chronicle reported Notwithstanding

the unfavourable weather this large room was densely crowded, and it

was evident from the deep and anxious attention manifested by the

audience, and the frequent and hearty cheering, that there are many in

the City of London fully alive to the importance and great necessity of

such institutions as these. It appears that this association is causing

great inquiry among the operative classes of this great metropolis, and

exciting the attention of the upper classes.

For part of its brief history, the chapel

was associated with

the Protestant Association,

whose journal The

Penny Protestant Operative reports

various meetings of the local branch, the Tower Hamlets Operative

Protestant Association, in the Cannon Street Road schoolroom and

elsewhere in the borough. For example, in 1840 the

Revd J.

Cotter (from Ireland) delivered a lecture here on

the state of Romanism in Ireland, and the pleasing circumstances

connected with the numerous converts from Popery at Dingle and

Ventry, and exhibited specimens of indulgences and beads. The room

was crowded, and two or three hundred persons were unable to obtain

admission. A collection of £4 10s was taken for a school in Dingle. Monthly meetings of the association's Mutual Instruction Class were held in the schoolroom. As the following shows, several of the ministers of the chapel were active supporters. See here

for another Irish clergyman's involvement with the meetings of the

Association, and his later links with St Matthew Pell Street: in October 1841 he was a speaker at a

meeting of the City of London Tradesmen and Operative Protestant

Association held in the George Hall, Aldermanbury, chaired by James

Harris [see below]: the St James Chronicle reported Notwithstanding

the unfavourable weather this large room was densely crowded, and it

was evident from the deep and anxious attention manifested by the

audience, and the frequent and hearty cheering, that there are many in

the City of London fully alive to the importance and great necessity of

such institutions as these. It appears that this association is causing

great inquiry among the operative classes of this great metropolis, and

exciting the attention of the upper classes.

Ministers of

the chapel

The meeting mentioned above was chaired by the Minister, James

Harris.

Some of these details require corroboration, but he appears to have

been ordained, as a graduate of Trinity College Dublin, in 1812 as

curate both at St Leonard Shoreditch (on a stipend of £100, with an endorsement on foregoing his licence) and St Margaret Lothbury & St Christopher le Stocks, in the City (on a stipend of £75, with the consent of the Rector, the Revd Dr Whitfield).

He seems to have taken on the lease of Spring Gardens [later St Matthew's] Chapel,

in the parish of St Martin in the Fields [right - built

in 1731, it seated 300; after compulsory purchase, it was used from

1885 to store Admiralty records, and was demolished in 1903]. While in

this area, he sometimes attended lectures

at the nearby premises of the Outinian Society (founded as the

Matrimonial Society by John Penn

in 1818 to encourage young men and women to marry). This lease of the

chapel having been 'demised' [transferred] to him in 1821, three years later

he was the plaintiff in a case for ejectment, for non-payment of rent: Doe dem. Harris v. Masters,

reported at 2 Barnewell & Cresswell 490 ('Doe' being a fictional

plaintiff for this purpose). In 1824 he was licensed as Lecturer of St

Mary Stratford, Bow, and the following year his Dublin degree was

recognised ad eundam

by Cambridge University (a courtesy practice of the time which fell

into abeyance).

He seems to have taken on the lease of Spring Gardens [later St Matthew's] Chapel,

in the parish of St Martin in the Fields [right - built

in 1731, it seated 300; after compulsory purchase, it was used from

1885 to store Admiralty records, and was demolished in 1903]. While in

this area, he sometimes attended lectures

at the nearby premises of the Outinian Society (founded as the

Matrimonial Society by John Penn

in 1818 to encourage young men and women to marry). This lease of the

chapel having been 'demised' [transferred] to him in 1821, three years later

he was the plaintiff in a case for ejectment, for non-payment of rent: Doe dem. Harris v. Masters,

reported at 2 Barnewell & Cresswell 490 ('Doe' being a fictional

plaintiff for this purpose). In 1824 he was licensed as Lecturer of St

Mary Stratford, Bow, and the following year his Dublin degree was

recognised ad eundam

by Cambridge University (a courtesy practice of the time which fell

into abeyance).  At some point he took on the proprietary Episcopal chapel in Portman Square, Baker Street (built around 1779 - right]

but gave this up after the death of his

wife and child - one suggestion is that his brother took it over. (It

continued to be a base for the Protestant Association, with various

publications in the 1850s by the minister, John William Reeve.) He was

a freemason, and a chaplain to the

grand lodge of the Loyal Orange Institution (whose president was HRH Prince Ernest, Duke of

Cumberland), though in his intriguing evidence to the 1835 Royal

Commission on Orange Institutions - transcribed and commented on here

- he claimed his involvement, and knowledge of its activities, had been

limited after the loss of his family. Whatever the case, his Irish

Protestant sympathies suited him well for the post at

Trinity Chapel; in 1839 the congregation there presented him with a

glowing testimonial.

At some point he took on the proprietary Episcopal chapel in Portman Square, Baker Street (built around 1779 - right]

but gave this up after the death of his

wife and child - one suggestion is that his brother took it over. (It

continued to be a base for the Protestant Association, with various

publications in the 1850s by the minister, John William Reeve.) He was

a freemason, and a chaplain to the

grand lodge of the Loyal Orange Institution (whose president was HRH Prince Ernest, Duke of

Cumberland), though in his intriguing evidence to the 1835 Royal

Commission on Orange Institutions - transcribed and commented on here

- he claimed his involvement, and knowledge of its activities, had been

limited after the loss of his family. Whatever the case, his Irish

Protestant sympathies suited him well for the post at

Trinity Chapel; in 1839 the congregation there presented him with a

glowing testimonial.

During this period the chapel had affiliated to

the

General Society for Promoting District

Visiting, set up in

1828 by a variety of evangelical groups, with some episcopal

support (in 1832 the Bishop of Chester had preached for the Society at Harris' Portman Square Chapel), with the object of promoting

a general and systematic visitation of the poor, with a view to

improving their temporal and spiritual condition. Within

three years, London had been divided into 866 sections, with 25 local

District Visiting Societies drawing on 573 regular lay visitors who

made 163,695 visits in 1831. The following year's District Visitors

Record claims a

regular system of domiciliary visitation was thought to be necessary,

by which every poor family might be visited at their habitations,

from house to house and from room to room, and their temporal and

spiritual condition diligently yet tenderly examined into, and

appropriate treatment applied.

But some were suspicious of the Society's methods, since although they

recommended communicating and co-operating with the local incumbent

before a District Society was set up, of which ideally he should be the

president, they reserved the right to set up a Society even should the sanction of the

clergyman be withheld. In 1840 they produced a manual

by Thomas Dale

(a residentiary canon of St Paul's and Vicar of St Bride Fleet Street) with a

preface by Bishop Blomfield of London, commending the system but

commenting There

is a special promise of blessing annexed to ministerial service; and

the sense of that speciality ought not to be effaced from the minds

of our flocks, by the permitted intrusion of laymen, however pious

and zealous, into that which belongs to our own peculiar office. If

this be not attended to, you must expect that tares will spring up in

the wheat, and that your visiting societies will become so many

nurseries of schism.

See this anti-Catholic rant delivered at the Society's meeting in 1836 by the Revd Hugh Stowell, the famous evangelical preacher and church-builder from Salford.

James Harris left in 1842

to become incumbent of All Saints Spicer Street, Mile End New Town.

There he chaired the church's auxiliary branch of the Scripture Readers'

Association (contributing £12 3s 9d to funds in 1853), and was a

council member of the newly-formed Association for

the Promotion of Improved Street Paving, Cleansing and Drainage.

The Church

Review of

1850, and other papers, reported that he was to become one of three

additional colonial

bishops, to serve in Western Australia (even though he was 65 at the

time) - the other two being Sierra Leone and Mauritius. But this did

not happen - no bishop was appointed until 1857. In 1859 he became

Vicar of Wellington and Curate of West

Buckland in Somerset (publishing Idiomatic Phrases and Expressions in French and English) and died there two years later.

Right is his bookplate: the blazon (heraldic description) is Two Hands Clasping Each Other, Couped At Wrist, Conjoined To A Pair Of Wings Proper. Each Wing Is Charged With A Mullet [not a fish or a hairstyle, but a spur wheel], with the motto domat omnia virtus - 'virtue overcomes all things'.

Right is his bookplate: the blazon (heraldic description) is Two Hands Clasping Each Other, Couped At Wrist, Conjoined To A Pair Of Wings Proper. Each Wing Is Charged With A Mullet [not a fish or a hairstyle, but a spur wheel], with the motto domat omnia virtus - 'virtue overcomes all things'.| A

new edition has been

issued of the much esteemed book of psalmody

first named above. The estimation in which it is held proves its merits

to a certain extent. It is, no doubt, one of the many books that have

in part arisen from the improved views of psalmody which mark our day,

and in part promoted those views and the corresponding practice. Among

these selections, however, we should not rank the one now before us by

any means first. The new compositions are not at all the best part of

the book, but many fine old tunes from different sources are

introduced. We think, however, that both as regards compositions and

arrangements, the popular taste and capacity have been too much

consulted in proportion to the classical merits of the music. This is

of course a question of degree, and the compilers have consistently

adhered in the matter to the views expressed in their preface as to

what is mainly required in modern church music. The "Supplemental Tune-book" is remarkable chiefly for the sources from which the tunes are derived. Those from the old Hebrew worship are of course especially interesting. It is always difficult for music of a new and somewhat foreign character to find its way into common favour and use, while the appearance of such novelties from time to time is exceedingly valuable. We think that several of the tunes in this small collection will be found fully worthy of introduction into our psalmody. |

The schoolroom was also used for various secular meetings. According to The Lancet, the

East London Medical Association met there in February 1842 to set up an

association for the suppression of illegal medical practitioners.

From 1844-48 Alfred

Bowen Evans was

the Minister (and from 1845 a curate of St George-in-the-East), no doubt appointed through the influence of Bryan King,

who had

recently become Rector of the parish church. Although of a markedly

different ecclesiastical tradition to his predecessors, his membership

of the Peace Society (like Charles Day, above), may have been a factor

in his appointment. He

had preached a course of

Advent sermons here

the

previous year, on

The Return of Jesus

Christ to our Earth, with its Attendant Events (published by Wertheim, who specialised in books on Christian-Jewish issues). The

registers show that he officiated at a considerable number of

baptisms and weddings at the parish church during his time here. Formerly a dissenting minister, and ordained by the Bishop of St David's in 1840, he

had been curate of Enfield, of Clodock in Herefordshire, and also Lecturer at the 'hyper-Tractarian'

church of St Andrew Wells Street in Marylebone, where in 1841 he had

published Dissent and

its Inconsistencies,

and had made his

mark as a preacher - he was only 4' 8" tall, and walked with a stoop,

but had a commanding presence - attracting large numbers of young men

to the

church and taking an uncompromisingly pacifist stance at the time of

the 'Russian war': war, he said, is 'utterly indefensible'.

Intriguingly, The

Train

('a first class magazine' - another Protestant journal) commended him

despite his churchmanship.

Another reviewer, commenting on his published discourses Christianity

in its Homely Aspects,

said

| The author of this volume of sermons wishes that it may fall into the hands of any who may have entertained a prejudice against the church in which they were delivered; and assuredly, if these sermons represent the doctrines preached in that church, we cannot well imagine a better answer to charges often brought against its clergy. The style of the discourses is peculiar and antiquated, and there is a good deal of reasoning which we should think above the comprehension of the average run of congregations; but the doctrines and principles enunciated appear to have no such tendencies as should furnish any ground of jealousy; on the contrary, we should say that they are particularly free from such notions, and that the most Protestant congregation in the metropolis might listen to them without any other feeling than that of gratification and interest. |

Evans' farewell sermon

at Trinity Episcopal Chapel was published as The

Dove: the Christian Pattern.

In

1852, then living at Kentish Town, he obtained a protection order

against bankruptcy; but he continued to publish sermons preached at St

Andrew Wells Street, including further thoughts about war. In 1855, in the wake of recruitment for the Crimean campaign, The Peace Society printed two pamphlets: War: Its Theologies; Its Anomalies; Its Incidents, and Its Humiliations and The

Soldier and the Christian: Addressed to All Willing to Hear Both Sides,

but Especially to Parents about to Choose a Profession for their

Sons, by a Clergyman of the Church of England. In the following year he produced a series

of Lectures

on Job.

In

1861 he became

Rector of St Mary-le-Strand (which he re-ordered on Tractarian

principles), living in the top floor of a slum off The Strand and

preaching to small but distinguished congregations (including Gladstone

and Lord Salisbury) until his death in 1878, and continuing to write

- for example, The

Future of the Human Race (1864), four sermons on Revelation 21 & 22. In that year, he was awarded a Lambeth Doctorate of Divinity. Here are some memories of a young friend, who took him on his first ever visit to a theatre at the age of 65.

In

1861 he became

Rector of St Mary-le-Strand (which he re-ordered on Tractarian

principles), living in the top floor of a slum off The Strand and

preaching to small but distinguished congregations (including Gladstone

and Lord Salisbury) until his death in 1878, and continuing to write

- for example, The

Future of the Human Race (1864), four sermons on Revelation 21 & 22. In that year, he was awarded a Lambeth Doctorate of Divinity. Here are some memories of a young friend, who took him on his first ever visit to a theatre at the age of 65.

In The Pulpit and

the Press he remarked that a man might preach Calvinism in a chasuble

or a surplice and it would

be declared to be Romanism, while he might preach Romanism in a Genevan

gown, and it would not be distinguished from Calvinism. He

supported the Rector of St George's, Bryan King, in his introduction of

choral services (pointing out in a sermon that the Psalms were intended

to be sung rather than 'read').

But Bryan King

presumably had little say in the appointment of Evans' successor in

1848 - Henry

Robbins,

son of the Rector of Heigham, in Norfolk, and of Wadham College Oxford, who since 1843 had been Head Master of

Stepney Proprietary Grammar School; he married Agnes Gooton in 1844. He restored

the hard-line Protestant tradition, having been a speaker at the

Protestant Association, and involved in the 1845 Anti-Maynooth

Conference, protesting at Parliament's proposals for grants and

endowments to a Roman Catholic college: the proceedings were written

up by A.S. Thelwall who was attached to St Matthew Pell Street. In

1853 a collection was taken for the Society

for Irish Church Missions to the Roman Catholics,

after a sermon by its Deputation Secretary. This organisation had been set up four

years earlier by Alexander Dallas, and continued until 1950.

At

the 23rd Annual General Meeting of the British Society for promoting

the Religious Principles of the Reformation in 1850 he seconded the

motion That the increased, and in

many cases successful, efforts of Romish Ecclesiastics in this country

to spread their unscriptural principles, and to pervert alike clergy

and laity to Romanism, demand that we should not merely stand on the

defensive, but with the open Bible, and in the spirit of love and

faithfulness, and prayer, and a sound mind, make aggressive inroads on

Romanism itself, as well as call on her people to come out of her, that

they partake not of her sins, and that they receive not of her plagues.

At

the 23rd Annual General Meeting of the British Society for promoting

the Religious Principles of the Reformation in 1850 he seconded the

motion That the increased, and in

many cases successful, efforts of Romish Ecclesiastics in this country

to spread their unscriptural principles, and to pervert alike clergy

and laity to Romanism, demand that we should not merely stand on the

defensive, but with the open Bible, and in the spirit of love and

faithfulness, and prayer, and a sound mind, make aggressive inroads on

Romanism itself, as well as call on her people to come out of her, that

they partake not of her sins, and that they receive not of her plagues.

How

did this chapel relate to its parish church and the distinctive

tradition that was emerging there? It presumably closed soon after

Robbins' death, and a few years before the consecration of nearby St Matthew Pell Street

as a district church (it had been a mission chapel since 1848 or so).

For some years it became St George's Wesleyan Free Church until, as

described here, they moved to other premises on Cannon Street Road. It was demolished around 1875, when

one of the new Raine's Schools

buildings was erected on the site, with the playground over part of the

old burial ground – as Mrs

Basil Holmes

reported in 1897, the remaining area comprised a cooper's yard (Hasted & Sons), a carter's yard (Seaward Brothers), and

sheds and

houses (shown right on Goad's 1899 insurance map). Right is the present-day site of

the chapel, a grassy area behind Norton House on the Bigland

Estate; see here for more details about this area today.

How

did this chapel relate to its parish church and the distinctive

tradition that was emerging there? It presumably closed soon after

Robbins' death, and a few years before the consecration of nearby St Matthew Pell Street

as a district church (it had been a mission chapel since 1848 or so).

For some years it became St George's Wesleyan Free Church until, as

described here, they moved to other premises on Cannon Street Road. It was demolished around 1875, when

one of the new Raine's Schools

buildings was erected on the site, with the playground over part of the

old burial ground – as Mrs

Basil Holmes

reported in 1897, the remaining area comprised a cooper's yard (Hasted & Sons), a carter's yard (Seaward Brothers), and

sheds and

houses (shown right on Goad's 1899 insurance map). Right is the present-day site of

the chapel, a grassy area behind Norton House on the Bigland

Estate; see here for more details about this area today.