Cable

Street

The

rich history of Cable Street [left - as it might have been in the 1830s], with its 'iconic' East End status, has

inspired many writings; see, most recently, Roger Mills Everything Happens in Cable Street (Five Leaves Publications 2011), and other works referrred to below. In 1963, Ian Nairn wrote 'Cable

Street, the whore's retreat': a shameful blot on the moral landscape of

London: an outworn slum area ... Its crime is not that it contains vice

but that it is unashamed and exuberant about it ... Nobody cares enough

and the whole place will soon be a memory.

Fortunately, he has been proved wrong, even though much of its history

is no longer physically visible, there are many who know and care about

the detailed records that are available.

The

rich history of Cable Street [left - as it might have been in the 1830s], with its 'iconic' East End status, has

inspired many writings; see, most recently, Roger Mills Everything Happens in Cable Street (Five Leaves Publications 2011), and other works referrred to below. In 1963, Ian Nairn wrote 'Cable

Street, the whore's retreat': a shameful blot on the moral landscape of

London: an outworn slum area ... Its crime is not that it contains vice

but that it is unashamed and exuberant about it ... Nobody cares enough

and the whole place will soon be a memory.

Fortunately, he has been proved wrong, even though much of its history

is no longer physically visible, there are many who know and care about

the detailed records that are available.

Cable

Street, running from the Tower of London in the west to Ratcliff in the

east, was originally the standard length of hemp rope, twisted into a

cable, required for sailing ships; there were various rope

walks in the area. In 1695 it was paved from the Windmill Inn to the

junction with Church Street (Anne Steele was among some local residents

who petitioned to be excused from the cost of this work). At one time

each part of the street bore different

names: from west to east, Cable Street, Knockfergus (because of the

many Irish residents), New Road, Back Lane [or Road], Bluegate Fields

[at one time the present-day Dellow Street was also so-named],

Sun Tavern

Fields and Brook Street. In addition, some sections had addresses as St

George's Place, Allington Place, Bath Terrace, Chaurgur Row,

Harper Place, Wellington Place and China Place, as shown on the 1862

map, right (still showing a rope walk). Chaurghur, or Chaur-Ghur, Row was an unusual name; the Edinburgh Review of 1870 included a long article on 'London Topography and Street-nomenclature' which comments The

foreign element in the sea-faring population at the East-end, in the

neighbourhood of the docks, is represented by Jamaica Street, Hong-Kong

Terrace, Chaur-Ghur Row (lately altered to Cable Street), Chin-Chu

Cottages, Bombay Street, and Norway Place; and an obscure thoroughfare

in Shoreditch retains the enviable appellation of the 'Land of Promise'; and it concludes with a call for the removal of pretentious, bombastic and pseudo-rural names - One,

at least, of the evils of an overgrown capital will be removed, when

necessity demands the complete revision of our modern

street-nomenclature.

Cable

Street, running from the Tower of London in the west to Ratcliff in the

east, was originally the standard length of hemp rope, twisted into a

cable, required for sailing ships; there were various rope

walks in the area. In 1695 it was paved from the Windmill Inn to the

junction with Church Street (Anne Steele was among some local residents

who petitioned to be excused from the cost of this work). At one time

each part of the street bore different

names: from west to east, Cable Street, Knockfergus (because of the

many Irish residents), New Road, Back Lane [or Road], Bluegate Fields

[at one time the present-day Dellow Street was also so-named],

Sun Tavern

Fields and Brook Street. In addition, some sections had addresses as St

George's Place, Allington Place, Bath Terrace, Chaurgur Row,

Harper Place, Wellington Place and China Place, as shown on the 1862

map, right (still showing a rope walk). Chaurghur, or Chaur-Ghur, Row was an unusual name; the Edinburgh Review of 1870 included a long article on 'London Topography and Street-nomenclature' which comments The

foreign element in the sea-faring population at the East-end, in the

neighbourhood of the docks, is represented by Jamaica Street, Hong-Kong

Terrace, Chaur-Ghur Row (lately altered to Cable Street), Chin-Chu

Cottages, Bombay Street, and Norway Place; and an obscure thoroughfare

in Shoreditch retains the enviable appellation of the 'Land of Promise'; and it concludes with a call for the removal of pretentious, bombastic and pseudo-rural names - One,

at least, of the evils of an overgrown capital will be removed, when

necessity demands the complete revision of our modern

street-nomenclature.

Cable Street was once a busier road than The Highway, until

the latter was widened in recent times and the Limehouse Link tunnel constructed in 1993. It is now a one-way street and

the route of 'CS3', one of the network of Cycle Super Highways

created for the Olympics, and painted blue (rather than the conventional green) because they were

sponsored by Barclay's Bank.

Along Cable Street cycles are separated from motor traffic, but

elsewhere the lanes are narrow strips at the edge of busy roads, and

fatal accidents have raised issues about their safety. See here for more details about public transport in and about the parish. Right is a drawing of Cable Street in the early 1960s from Geoffrey Fletcher Pearly Kingdom (Hutchinson 1965) and a 1970s oil painting by Noel Gibson.

Cable Street was once a busier road than The Highway, until

the latter was widened in recent times and the Limehouse Link tunnel constructed in 1993. It is now a one-way street and

the route of 'CS3', one of the network of Cycle Super Highways

created for the Olympics, and painted blue (rather than the conventional green) because they were

sponsored by Barclay's Bank.

Along Cable Street cycles are separated from motor traffic, but

elsewhere the lanes are narrow strips at the edge of busy roads, and

fatal accidents have raised issues about their safety. See here for more details about public transport in and about the parish. Right is a drawing of Cable Street in the early 1960s from Geoffrey Fletcher Pearly Kingdom (Hutchinson 1965) and a 1970s oil painting by Noel Gibson.

Local

people, having been promised a museum in a converted Cable Street shop

celebrating the achievements of East End women, we horrified to

discover when the frontage was revealed that they have been duped and

it is part of the Jack the Ripper 'industry' - a great pity. More here.

Wilton's Music Hall, Grace's Alley ~ Women's History Museum

The oldest surviving music

hall in the country (and now a Grade II* listed building, featuring on many websites, including this one), it was built by John

Wilton in 1858 in the back yard of five 1720's houses and incorporating his pub The Prince of Denmark Tavern (named for the Danish links with Wellclose Square) and

its famous mahogany bar. Used for a wide variety of musical and

dramatic events,

it could seat up to 1,800 people, with its barley-sugar pillared

galleries, and had been very successful, competing for a time with West

End theatres. Performers such as Champagne Charlie would speed over

from the West End to give a second performance here. Like other venues,

it promoted 'minstrel' entertainments,

with blacked-up performers, such as Thomas Duriah ('Negro Delineator

and End Man from the London Music Halls') who performed here in 1865.

But it finally failed in the 1870s, as purpose-built venues were

established elsewhere.

The oldest surviving music

hall in the country (and now a Grade II* listed building, featuring on many websites, including this one), it was built by John

Wilton in 1858 in the back yard of five 1720's houses and incorporating his pub The Prince of Denmark Tavern (named for the Danish links with Wellclose Square) and

its famous mahogany bar. Used for a wide variety of musical and

dramatic events,

it could seat up to 1,800 people, with its barley-sugar pillared

galleries, and had been very successful, competing for a time with West

End theatres. Performers such as Champagne Charlie would speed over

from the West End to give a second performance here. Like other venues,

it promoted 'minstrel' entertainments,

with blacked-up performers, such as Thomas Duriah ('Negro Delineator

and End Man from the London Music Halls') who performed here in 1865.

But it finally failed in the 1870s, as purpose-built venues were

established elsewhere.

One

innovation of the London Wesleyan Methodist Mission was to hire

premises as new-style mission

centres - what today

we would call 'fresh expressions' or 'café church'. In 1891 St George's Wesleyan Chapel, further along Cable Street, took over Wilton's, with

leadership from lay church members.

It was known popularly as the 'Old Mahogany Mission' after the bar. Peter Thompson, the minister (who faced a libel action during his

time) was challenged

for allowing the Hall to be used for a dock labourers' meeting to

protest against the 'contracting out' clauses of the Employers

Liability Bill. Interestingly, he did not regard this as a breach of

the Wesleyan 'no politics' rule, despite the dock strike of 1889 (when

2,000 meals a day were served here to strikers and their families); the

Independent Labour Party had only just been founded, and links

between unions and political parties were yet to develop.

It

was

very different in the 1930s, when Wilton's was a rallying point and a 'safe house' for

the Battle of Cable Street. During the Second World War, it provided refuge for people bombed out of their homes. The

Mission (which had also provided hostel accommodation for 30 people, mainly seafarers)

closed in 1956. In that year, the Rev Lesley E. Day published a pamphlet Sixty-Eight Glorious Years for Christ: the Story of the Old Mahogany Bar (East End Mission). The building was used to store rags [right - interior in the 1970s.]

It

was

very different in the 1930s, when Wilton's was a rallying point and a 'safe house' for

the Battle of Cable Street. During the Second World War, it provided refuge for people bombed out of their homes. The

Mission (which had also provided hostel accommodation for 30 people, mainly seafarers)

closed in 1956. In that year, the Rev Lesley E. Day published a pamphlet Sixty-Eight Glorious Years for Christ: the Story of the Old Mahogany Bar (East End Mission). The building was used to store rags [right - interior in the 1970s.]

There

were plans for demolition, but Sir John Betjeman was among those who

resisted this. Broomhill

Opera took it on, and among other things staged the first all-black

Carmen, South African mystery plays and a black version of The

Beggar’s Opera. In

its dilapidated state, it was used for film shoots, including Karel

Reisz’s Isadora with Vanessa Redgrave, The Krays (1990), Richard Attenborough's Chaplin (1992), Douglas

McGrath’s Nicholas Nickleby (2002), Woody

Allen’s Cassandra’s Dream, as well as music videos. Opera groups use it

regularly, and it is hired for private functions. It was an

unsuccessful candidate in the 2003 tv series 'Restoration',

but determined

efforts to save and restore the building continue. The bank's threat of

repossession the following year, to recoup debts of £250,000, was

staved off, and under the inspired leadership of Frances Mayhew [right] a

mix of performances, school events and other activities continues, and

the bar is regularly open and makes an excellent venue for small

meetings.

There

were plans for demolition, but Sir John Betjeman was among those who

resisted this. Broomhill

Opera took it on, and among other things staged the first all-black

Carmen, South African mystery plays and a black version of The

Beggar’s Opera. In

its dilapidated state, it was used for film shoots, including Karel

Reisz’s Isadora with Vanessa Redgrave, The Krays (1990), Richard Attenborough's Chaplin (1992), Douglas

McGrath’s Nicholas Nickleby (2002), Woody

Allen’s Cassandra’s Dream, as well as music videos. Opera groups use it

regularly, and it is hired for private functions. It was an

unsuccessful candidate in the 2003 tv series 'Restoration',

but determined

efforts to save and restore the building continue. The bank's threat of

repossession the following year, to recoup debts of £250,000, was

staved off, and under the inspired leadership of Frances Mayhew [right] a

mix of performances, school events and other activities continues, and

the bar is regularly open and makes an excellent venue for small

meetings.

Welcome news came in June 2013, with a grant from the Heritage Lottery

Fund (for which an the appeal was launched by David Suchet in 2011) of £1.85m towards

the £2.6m needed for full-scale restoration. Work due to be completed

in 2015 will secure its fragile structure, and make 40% more of the

building available for new uses as an arts and heritage venue (see East End Life issue 965). Right are four internal views, including the famous bar. Wilton's website is here. When the main auditorium was re-opened in 2013, one of the first productions was a splendid revival of Bill Owen's musical The Matchgirls, first

produced in 1988 to mark the centenary of the heroic first women's

strike by the workers at Bryant and May's factory in Bow (ironically,

the owners were Quakers). A former member of our congregation appeared

in a production three years later, produced by his son Tom Owen, at the

Queen's Theatre Hornchurch. See more about the matchgirls here.

Welcome news came in June 2013, with a grant from the Heritage Lottery

Fund (for which an the appeal was launched by David Suchet in 2011) of £1.85m towards

the £2.6m needed for full-scale restoration. Work due to be completed

in 2015 will secure its fragile structure, and make 40% more of the

building available for new uses as an arts and heritage venue (see East End Life issue 965). Right are four internal views, including the famous bar. Wilton's website is here. When the main auditorium was re-opened in 2013, one of the first productions was a splendid revival of Bill Owen's musical The Matchgirls, first

produced in 1988 to mark the centenary of the heroic first women's

strike by the workers at Bryant and May's factory in Bow (ironically,

the owners were Quakers). A former member of our congregation appeared

in a production three years later, produced by his son Tom Owen, at the

Queen's Theatre Hornchurch. See more about the matchgirls here.

Round

the corner from Wiltons, there are plans to develop no.12 Cable Street

into a Women's History Museum, focusing particularly on women of the

East End.

The birth of Harrods

4

Cable Street is an unlikely setting for the origins of the famous West

End emporium, but in 1834 Charles Henry Harrod, aged 35, set up a

wholesale grocery and tea merchant's store here, living nearby in

Rosemary Lane. It remained here probably until 1855, by which time he

had another branch at Eastcheap, and began the move to Knightsbridge in

1863. (Most department stores began as drapers' shops.) It was his

son Charles Digby Harrod who began the expansion in the 1860s, and the

rest is history!

4

Cable Street is an unlikely setting for the origins of the famous West

End emporium, but in 1834 Charles Henry Harrod, aged 35, set up a

wholesale grocery and tea merchant's store here, living nearby in

Rosemary Lane. It remained here probably until 1855, by which time he

had another branch at Eastcheap, and began the move to Knightsbridge in

1863. (Most department stores began as drapers' shops.) It was his

son Charles Digby Harrod who began the expansion in the 1860s, and the

rest is history!

The site is now a noodle bar and

grill [left]. From

the 1830s until the end of the 19th century, Harrod's Court was a small

alley running from the south-west corner of Wellclose Square into Well

Street [now Ensign Street], though Weller's map of 1868 lists it as

Hard's Place, and another source as Harrald's Place, so the connection

with the family is uncertain.

When the

1855 Metropolis

Management Act

created

a new system of local government for London, with an elected Vestry for

each parish, a Vestry Hall was built in 1861 to serve the parish of St

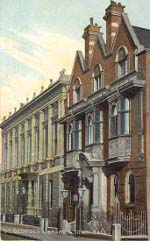

George-in-the-East. It is of Portland stone, with an Italianate façade [left: old postcard, with Library still standing; today, showing the mural; right, fanlight], at a cost of

£6,000, and had a handsome interior. The Buildings of England (London 5: East), by Bridget Cherry, Charles O'Brian and Nicolaus Pevsner (Yale UP 2005) comments on public offices of this time: Most

buildings date from the 1860s onwards and are eclectic, often crude

interpretations of the polite civic architecture of the mid C19

metropolis: St George's, Cable Street, is the earliest, of 1860 by

Andrew Wilson, emulating the solid Italianate popularized by Charles

Barry's Travellers Club in the 1840s. Wilson was the son of Joshua Wilson,

builder and warden of St George-in-the-East in 1854-55, with whom he

had been in partnership before he became an architect, with an office

at 34 Cannon Street Road prior to moving to Bow.

When the

1855 Metropolis

Management Act

created

a new system of local government for London, with an elected Vestry for

each parish, a Vestry Hall was built in 1861 to serve the parish of St

George-in-the-East. It is of Portland stone, with an Italianate façade [left: old postcard, with Library still standing; today, showing the mural; right, fanlight], at a cost of

£6,000, and had a handsome interior. The Buildings of England (London 5: East), by Bridget Cherry, Charles O'Brian and Nicolaus Pevsner (Yale UP 2005) comments on public offices of this time: Most

buildings date from the 1860s onwards and are eclectic, often crude

interpretations of the polite civic architecture of the mid C19

metropolis: St George's, Cable Street, is the earliest, of 1860 by

Andrew Wilson, emulating the solid Italianate popularized by Charles

Barry's Travellers Club in the 1840s. Wilson was the son of Joshua Wilson,

builder and warden of St George-in-the-East in 1854-55, with whom he

had been in partnership before he became an architect, with an office

at 34 Cannon Street Road prior to moving to Bow.

Further local government reform came with the

1899 London

Government Act

which replaced all the Vestries across London with 28 Borough Councils.

The new Stepney Borough

Council took over the building as a local Town Hall until a new one

could be built, and the coroner's court was located there.

Further local government reform came with the

1899 London

Government Act

which replaced all the Vestries across London with 28 Borough Councils.

The new Stepney Borough

Council took over the building as a local Town Hall until a new one

could be built, and the coroner's court was located there.

The

Vestry was keen to build a public library, but only had power to raise

1d. on the rates, yielding £600 for the running costs. Public donations

were sought, and John

Passmore Edwards,

the 'Cornish Carnegie', made a major contribution. (He also funded the

Passmore Edwards Sailors' Palace, on West India Dock Road, for the

British and Foreign Sailors Society.) It was

built, in Portland stone and

brick, to the right of the Town Hall [left - drawing

of 1898],

running down the side of Prospect [now Library] Place. Goad's 1899 insurance map - right - shows the adjacent Library, Vestry Hall (under extension at the time) and Wesleyan Chapel. The foundation

stone was laid on 28 September 1897,

and Lord Russell, the Lord Chief Justice, opened it in October 1898. A

children's library was added in 1929.

The

Vestry was keen to build a public library, but only had power to raise

1d. on the rates, yielding £600 for the running costs. Public donations

were sought, and John

Passmore Edwards,

the 'Cornish Carnegie', made a major contribution. (He also funded the

Passmore Edwards Sailors' Palace, on West India Dock Road, for the

British and Foreign Sailors Society.) It was

built, in Portland stone and

brick, to the right of the Town Hall [left - drawing

of 1898],

running down the side of Prospect [now Library] Place. Goad's 1899 insurance map - right - shows the adjacent Library, Vestry Hall (under extension at the time) and Wesleyan Chapel. The foundation

stone was laid on 28 September 1897,

and Lord Russell, the Lord Chief Justice, opened it in October 1898. A

children's library was added in 1929.

Passmore Edwards also gave two stone sculptures, representing Literature and Art [left],

which were set on either side of the curved pediment of the porch which

was flanked by massive Ionic columns. They were the work of Nathaniel

Hitch

(1845-1938), who had trained with the architectural sculptors

Farmer & Brindley and produced a great deal of work for churches

and other buildings for the leading architects of the day, including

H.P. Burke Downing, H. Fuller Clark, W.D. Caröe, Paul Waterhouse and

T.H. Lyon and particularly John and Frank Loughborough Pearson. His

firm was based at 60 Harleyford Road, Battersea, and his son Frederick

Brook Hitch continued the work. For more on Hitch, including a

forthcoming catalogue of his papers (held at the Henry Moore Archive in

Leeds) by Gordon Lawson, see here.

Passmore Edwards also gave two stone sculptures, representing Literature and Art [left],

which were set on either side of the curved pediment of the porch which

was flanked by massive Ionic columns. They were the work of Nathaniel

Hitch

(1845-1938), who had trained with the architectural sculptors

Farmer & Brindley and produced a great deal of work for churches

and other buildings for the leading architects of the day, including

H.P. Burke Downing, H. Fuller Clark, W.D. Caröe, Paul Waterhouse and

T.H. Lyon and particularly John and Frank Loughborough Pearson. His

firm was based at 60 Harleyford Road, Battersea, and his son Frederick

Brook Hitch continued the work. For more on Hitch, including a

forthcoming catalogue of his papers (held at the Henry Moore Archive in

Leeds) by Gordon Lawson, see here.

The

library was destroyed in the Blitz in 1941. (The sculptures - minus

their heads - can be discerned in photographs following the bomb damage.) A temporary building

in St George's Gardens was later provided, until a new library was

constructed in Watney Street in the 1960s. The site now forms the entrance to St George's Gardens.

On

the wall of the Library (now on the front of the Town Hall) a small plaque was affixed to commemorate

those who fought and died in the International Brigade, supporting the

anti-fascist forces in the Spanish Civil War against General Franco,

who was supported by Hitler and Mussolini. The rallying-cry was no pasaran - 'they

shall not pass'. Their action inspired Ernest Hemingway's For

Whom the Bell Tolls,

and

the bombing of villages by Nazi aircraft prompted Picasso's Guernica. See here for the former Britannia Arms in Library Place.

On

the wall of the Library (now on the front of the Town Hall) a small plaque was affixed to commemorate

those who fought and died in the International Brigade, supporting the

anti-fascist forces in the Spanish Civil War against General Franco,

who was supported by Hitler and Mussolini. The rallying-cry was no pasaran - 'they

shall not pass'. Their action inspired Ernest Hemingway's For

Whom the Bell Tolls,

and

the bombing of villages by Nazi aircraft prompted Picasso's Guernica. See here for the former Britannia Arms in Library Place.

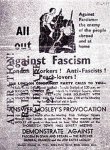

'They

shall not pass' became

the slogan of those who resisted

the legal

but provocative, and anti-Semitic, march of Sir Oswald Mosley and the

'Blackshirts' - the

British Union of Fascists - through the heavily-Jewish East End on 4

October

1936. Attempts to ban the march had failed, and the police were

there

in force to escort the marchers. Despite the appeals of religious and

political

leaders

to stay away, the marchers were resisted by many thousands from a

diverse range of groups - trade unions, and socialist, communist and

anarchist organisations (see here

for the part played by Fr Groser and the Stepney Tenants Defence

League), though many came from outside too. According to a participant Joe Bloomberg the local boys, men and women literally lifted the cobblestones out of the road, and built barricades to stop them marching. It

was a violent conflict, with the main fighting around what was then

known as Gardiner's Corner*, by Aldgate, but barricades were erected at

three points around Cable Street - which is why the plaque [above] is fixed to a wall near the corner of Dock Street. Their resistance succeeded; and the 1936 Public

Order Act was

passed as a result of the disturbances, requiring police permission for marches and banning

the wearing of political uniforms in public.

'They

shall not pass' became

the slogan of those who resisted

the legal

but provocative, and anti-Semitic, march of Sir Oswald Mosley and the

'Blackshirts' - the

British Union of Fascists - through the heavily-Jewish East End on 4

October

1936. Attempts to ban the march had failed, and the police were

there

in force to escort the marchers. Despite the appeals of religious and

political

leaders

to stay away, the marchers were resisted by many thousands from a

diverse range of groups - trade unions, and socialist, communist and

anarchist organisations (see here

for the part played by Fr Groser and the Stepney Tenants Defence

League), though many came from outside too. According to a participant Joe Bloomberg the local boys, men and women literally lifted the cobblestones out of the road, and built barricades to stop them marching. It

was a violent conflict, with the main fighting around what was then

known as Gardiner's Corner*, by Aldgate, but barricades were erected at

three points around Cable Street - which is why the plaque [above] is fixed to a wall near the corner of Dock Street. Their resistance succeeded; and the 1936 Public

Order Act was

passed as a result of the disturbances, requiring police permission for marches and banning

the wearing of political uniforms in public.

the curious story of the involvement of

'Kid' Lewis, a local Jewish boxer, in Mosley's movement, and his dramatic

resignation

the curious story of the involvement of

'Kid' Lewis, a local Jewish boxer, in Mosley's movement, and his dramatic

resignation

The mural

The mural

Anniversary commemorations have been held in recent years; here

and here are some pictures of the 70th in 2006. For the 75th anniversary in 2011, a full programme of activities and events was arranged by a various groups and at several venues

- see the programme - and the mural was again restored, by Paul Butler (see this

interview), and an interpretation board added. Events in St George's

Gardens on the Saturday provided a photo-opportunity for the Mayor

and councillors, as well as some excellent performances by amateur and

professional groups. On the Sunday, there was a march with over 1,000

participants from Aldgate to the mural, where speeches were made (it

just managed to escape the 30-day ban on marches imposed to restrict

the English Defence League's attempt to cause trouble in the East End

the previous month, with Muslims rather than Jews as the target),

followed by a programme of events at Wilton's,

culminating in a concert starring Billy Bragg. The range of groups on

the march matched those who had been there in 1936 (plus a few

Bangladeshi groups), and the redoubtable 96-year old Max Levitas [right], formerly a Jewish

communist councillor for Stepney, was a speaker on both days.

Hetty Bower, 106 the following day, and others who were present in

1936, also took part in the march.

Anniversary commemorations have been held in recent years; here

and here are some pictures of the 70th in 2006. For the 75th anniversary in 2011, a full programme of activities and events was arranged by a various groups and at several venues

- see the programme - and the mural was again restored, by Paul Butler (see this

interview), and an interpretation board added. Events in St George's

Gardens on the Saturday provided a photo-opportunity for the Mayor

and councillors, as well as some excellent performances by amateur and

professional groups. On the Sunday, there was a march with over 1,000

participants from Aldgate to the mural, where speeches were made (it

just managed to escape the 30-day ban on marches imposed to restrict

the English Defence League's attempt to cause trouble in the East End

the previous month, with Muslims rather than Jews as the target),

followed by a programme of events at Wilton's,

culminating in a concert starring Billy Bragg. The range of groups on

the march matched those who had been there in 1936 (plus a few

Bangladeshi groups), and the redoubtable 96-year old Max Levitas [right], formerly a Jewish

communist councillor for Stepney, was a speaker on both days.

Hetty Bower, 106 the following day, and others who were present in

1936, also took part in the march.

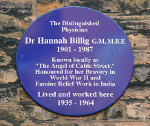

At 198

Cable Street [now by the entrance to Hawksmoor Mews] there is a plaque to Dr Hannah

Billig, 'the Angel of Cable

Street' - nearby Angel Mews is presumably named for her - who lived and worked here from

1935-64. Four

of the six children of Barnet and Millie Billig, Russian Jewish

emigrés, qualified as

doctors. Hannah has worked at the Jewish

Maternity Hospital before setting up her practice, and in the days

before the NHS turned no-one away because they couldn't pay.

At 198

Cable Street [now by the entrance to Hawksmoor Mews] there is a plaque to Dr Hannah

Billig, 'the Angel of Cable

Street' - nearby Angel Mews is presumably named for her - who lived and worked here from

1935-64. Four

of the six children of Barnet and Millie Billig, Russian Jewish

emigrés, qualified as

doctors. Hannah has worked at the Jewish

Maternity Hospital before setting up her practice, and in the days

before the NHS turned no-one away because they couldn't pay.

The row of houses between the Town Hall and Cannon

Street Road where her plaque is set (now by the entrance to modern apartments in Hawksmoor

Mews)

was restored in 1978; together with the houses/shops around the corner

in Cannon Street Road, these are the only remaining Georgian properties

in the vicinity of the church. Goad's 1899 insurance map [right] details them, together with the nine houses of Library Place [now demolished] and the school behind, now converted into flats.

The row of houses between the Town Hall and Cannon

Street Road where her plaque is set (now by the entrance to modern apartments in Hawksmoor

Mews)

was restored in 1978; together with the houses/shops around the corner

in Cannon Street Road, these are the only remaining Georgian properties

in the vicinity of the church. Goad's 1899 insurance map [right] details them, together with the nine houses of Library Place [now demolished] and the school behind, now converted into flats. Boxing

was one of the few possible routes to fame for deprived urban boys: see here for the example of 'Johnny Brown' 1902-76; in particular, it was

a channel for the energies of Jewish lads, drawn by anti-Semitic taunts

into street fighting.

Ted 'Kid' Lewis,

born Gershon Mendeloff to Russian parents in Umberston Street in 1893,

was encouraged by a local policeman to take up training at the Judean

Soul and Athletic (Temperance) Club at 54-56 Prince's Square. By 18, he

was fighting at Premierland in Backchurch Lane (where other Jewish boxers began their careers), Wonderland (off

Whitechapel Road) and the Ring at Blackfriars; he became British

flyweight champion in 1913 (winning the Lonsdale Belt), world

welterweight champion in 1915, and British and European middleweight

champion in 1921, and retired in 1929. Despite earning an estimated

$500,000 in the USA, he was generous and a gambler, so in 1931 he

accepted a job as Oswald Mosley's physical youth training instructor at

£60pw, recruiting local thugs as 'Biff Boys' - Mosley's bodyguard -

until the following year he realised the true, and anti-Semitic, nature

of Mosley's politics, and resigned, knocking Mosley and a couple of his

henchmen across the room. More details here, and in his film producer son Morton Lewis' biography Ted Kid Lewis: His Life and Times

(Robson 1990). From 1966 until his death four years later Lewis lived

at Nightingale House, the Jewish residential and nursing home in

Wandsworth Common (where his blue plaque is) - this had 19th century

roots in Wellclose Square. He was buried at the Jewish Cemetery in East Ham.

Ted 'Kid' Lewis,

born Gershon Mendeloff to Russian parents in Umberston Street in 1893,

was encouraged by a local policeman to take up training at the Judean

Soul and Athletic (Temperance) Club at 54-56 Prince's Square. By 18, he

was fighting at Premierland in Backchurch Lane (where other Jewish boxers began their careers), Wonderland (off

Whitechapel Road) and the Ring at Blackfriars; he became British

flyweight champion in 1913 (winning the Lonsdale Belt), world

welterweight champion in 1915, and British and European middleweight

champion in 1921, and retired in 1929. Despite earning an estimated

$500,000 in the USA, he was generous and a gambler, so in 1931 he

accepted a job as Oswald Mosley's physical youth training instructor at

£60pw, recruiting local thugs as 'Biff Boys' - Mosley's bodyguard -

until the following year he realised the true, and anti-Semitic, nature

of Mosley's politics, and resigned, knocking Mosley and a couple of his

henchmen across the room. More details here, and in his film producer son Morton Lewis' biography Ted Kid Lewis: His Life and Times

(Robson 1990). From 1966 until his death four years later Lewis lived

at Nightingale House, the Jewish residential and nursing home in

Wandsworth Common (where his blue plaque is) - this had 19th century

roots in Wellclose Square. He was buried at the Jewish Cemetery in East Ham.

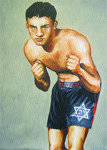

Lewis was the role model for Jack 'Kid' Berg, born Judah

Bergman

in 1909 above a fish shop in Christian Street, off Cable Street. He was

apprenticed as a lather boy in a barber's shop, trained at the Oxford

and St George's Club on Betts Street and began his career at Premierland when

he was 14. He fought

his first professional bout the following year. He first boxed in the

USA in 1928, and was World Junior Welterweight Champion in 1930 -

knocking out a fellow-Jewish boxer at the Albert Hall. He lost the

title the following year, but became British lightweight champion in

1934 (again defeating a fellow-Jew, Harry Mizler). In his career, which

lasted until 1945, when he was 36, he won 157 bouts, drew 9 and lost

26, making him

statistically the most successful world champion Britain ever produced

(today he would have been a 'superstar').

Lewis was the role model for Jack 'Kid' Berg, born Judah

Bergman

in 1909 above a fish shop in Christian Street, off Cable Street. He was

apprenticed as a lather boy in a barber's shop, trained at the Oxford

and St George's Club on Betts Street and began his career at Premierland when

he was 14. He fought

his first professional bout the following year. He first boxed in the

USA in 1928, and was World Junior Welterweight Champion in 1930 -

knocking out a fellow-Jewish boxer at the Albert Hall. He lost the

title the following year, but became British lightweight champion in

1934 (again defeating a fellow-Jew, Harry Mizler). In his career, which

lasted until 1945, when he was 36, he won 157 bouts, drew 9 and lost

26, making him

statistically the most successful world champion Britain ever produced

(today he would have been a 'superstar').

Though from an Orthodox Jewish

family (his parents were emigrants from Odessa and originally opposed his career as a sell-out to goyische midos, or heathen morals), he was not observant, but boxed with a

Star of David on his trunks, and put on tefillin

before his fights, partly to court the Jewish punters - especially when

he was fighting Italian or Irish-American opponents - and

also because he was somewhat superstitious. As one commentator put it, he knew it couldn't hurt to have God on your side.

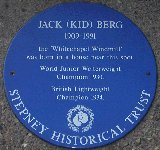

His biography The Whitechapel Windmill (Robson 1987), which he wrote with John Harding, chronicles his rise to fame and

his flamboyant lifestyle, said to have included a fling with Mae West.

During and after his boxing career, he appeared in films - a British silent film Sporting Life in the 1920s, Money Talks (1933) and The Square Ring (1953)

- and was a stuntman in Hollywood and for a Carry On film. A long-term friend was the Jewish East

End gangster Jack Spot. In later

life he was a familiar figure at the ringside and around London in his

red car. His cousin Howard Frederics wrote an opera about his

life, also called The Whitechapel Windmill, which was performed in 2005 under the sponsorship of the Jewish East End Celebration Society.The

blue plaque on Noble Court, Cable Street, near Jack's birthplace, was

unveiled at a ceremony with the Chief Rabbi, the Bishop of Stepney

(Richard Chartres, now Bishop of London), Professor Bill Fishman, Councillor Albert Lille and

the Retired Boxers Federation, followed by a charity ball which raised

over £1000.

His biography The Whitechapel Windmill (Robson 1987), which he wrote with John Harding, chronicles his rise to fame and

his flamboyant lifestyle, said to have included a fling with Mae West.

During and after his boxing career, he appeared in films - a British silent film Sporting Life in the 1920s, Money Talks (1933) and The Square Ring (1953)

- and was a stuntman in Hollywood and for a Carry On film. A long-term friend was the Jewish East

End gangster Jack Spot. In later

life he was a familiar figure at the ringside and around London in his

red car. His cousin Howard Frederics wrote an opera about his

life, also called The Whitechapel Windmill, which was performed in 2005 under the sponsorship of the Jewish East End Celebration Society.The

blue plaque on Noble Court, Cable Street, near Jack's birthplace, was

unveiled at a ceremony with the Chief Rabbi, the Bishop of Stepney

(Richard Chartres, now Bishop of London), Professor Bill Fishman, Councillor Albert Lille and

the Retired Boxers Federation, followed by a charity ball which raised

over £1000.

Elliott Tucker's 2007 film Ghetto Warriors

(viewable online) tells the tale of the phenomenon of the Jewish

boxers of the East End. Other Jewish boxing clubs in the area were Oxford and St George's and 'The Hutch'.

Among local non-Jewish boxers was (William Thomas) Billy 'Bombadier' Wells

(1889-1967), whose family lived at 250 Cable Street. He left school at

12, worked as a messenger boy and became a Royal Artillery gunner,

rising to the rank of bombadier. He became a professional boxer in 1910

after winning the all-India army boxing championship at Rawalpindi, and

gained and held the heavyweight title for eight years; he never lost on

points and won the first heavyweight Lonsdale belt, boxing until

1925. In 1935 he also became famous as the first gong-striker for

J. Arthur Rank films (though the gong was in fact made of papier-mâché,

and the sound provided by percussionist James Blades striking a 30"

Chinese tam-tam). There have been several others since.

Among local non-Jewish boxers was (William Thomas) Billy 'Bombadier' Wells

(1889-1967), whose family lived at 250 Cable Street. He left school at

12, worked as a messenger boy and became a Royal Artillery gunner,

rising to the rank of bombadier. He became a professional boxer in 1910

after winning the all-India army boxing championship at Rawalpindi, and

gained and held the heavyweight title for eight years; he never lost on

points and won the first heavyweight Lonsdale belt, boxing until

1925. In 1935 he also became famous as the first gong-striker for

J. Arthur Rank films (though the gong was in fact made of papier-mâché,

and the sound provided by percussionist James Blades striking a 30"

Chinese tam-tam). There have been several others since.

There is no blue plaque for 'Tex' [self-image left],

but he lived for many years in Cable Street, in a now-demolished house

opposite Noble Court. Born in Nigeria, he settled here in 1949, and as

a talented self-taught photographer chronicled everyday scenes of local

life, especially of black and Asian people, for over three decades - example right -

asking people to stop in the street so that he could take their pictures.

He died in 1994, leaving a vast collection of images, some of

which was showcased at the Spitz Gallery, Commercial Street in 1992.

There is no blue plaque for 'Tex' [self-image left],

but he lived for many years in Cable Street, in a now-demolished house

opposite Noble Court. Born in Nigeria, he settled here in 1949, and as

a talented self-taught photographer chronicled everyday scenes of local

life, especially of black and Asian people, for over three decades - example right -

asking people to stop in the street so that he could take their pictures.

He died in 1994, leaving a vast collection of images, some of

which was showcased at the Spitz Gallery, Commercial Street in 1992.

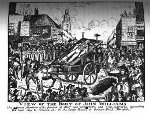

Interment of John Williams, the murdererAt about ten o'clock on Monday night, Mr Robinson, the high constable of the parish of St George, accompanied by Mr. Machin, one of the constables, Mr. Harrison, the collector, and Mr Robinson's deputy, went to the prison at Coldbath-Fields, where the body of Williams being delivered to them, was put into a hackney-coach, in which the deputy-constable proceeded to the watch-house of St George, known by the name of the Round-About, at the bottom of Ship-alley. The other three gentlemen followed in another coach, and about twelve o'clock the body was deposited in the black-hole, where it remained all night.Yesterday morning, about nine o'clock, the high constable, with his attendants, arrived at the watch-house with a cart, that had been fitted up for the purpose of giving the greatest possible degree of exposure to the face and body of Williams. A stage, or platform, was formed upon the cart by boards, which extended from one side to the other. They were fastened to the top, and lapping over each other from the hinder part to the front of the cart, in regular gradation, they formed an inclined plane, on which the body rested, with the head towards the horse, and so much elevated, as to be completely exposed to public view. The body was retained in an extended position by a cord, which, passing beneath the arms, was fastened underneath the boards. On the body was a pair of blue cloth pantaloons, and a white shirt, with the sleeves tucked Up to the elbows, but neither coat or waistcoat. About the neck was the white handkerchief with which Williams put an end to his existence. There were stockings but no shoes upon his feet. The countenance was fresh, and perfectly free from discolouration of livid spots. The hair was rather of a sandy cast, and the whiskers appeared to have been remarkably close shaven. On both the hands were some livid spots. On the right-hand side of the head was fixed, perpendicularly, the maul, with which the murder of the Marrs was committed. On the left also, in a perpendicular position, was fixed the ripping chissel. Above his head was laid, in a transverse direction upon the boards, the iron crow; and parallel with it, the stake destined to be driven through the body. About half past ten, the procession moved from the watch-house, in the following order:Mr Machin, constable of Shadwell.

An immense cavalcade of the inhabitants of the two parishes closed the procession. |

Back to History page | Back to Church & Churchyard | Back to Precinct of Wellclose | Back to Backchurch Lane | Back to Cable Street Directory 1921