Local judges (1) - stipendiary magistrates and county court judges

Stipendiary magistrates - Lambeth Street and Thames Courts

The Hon George Chapple Norton

(1800-75): grandson of Baron Grantley, who was nicknamed 'Sir Bull-face

Double Fee' because of his success in geting government legal

appointments, and son of the well-paid Baron of the Exchequer in

Scotland, he attended Edinburgh University but does not appear to have

graduated. Through family connections, he became Tory MP for Guildford

1826-30, voting mainly with the party line. Appointed Recorder of

Guildford, his Whitechapel magistracy (with a salary of £1,000)

debarred him from standing again for Parliament. This post was fixed by

his wife Caroline [right, by George Hayer 1832], daughter of the playwright Sheridan, and herself a considerable

writer - with Lord Melbourne, the Home Secretary. Not only was

she from a family with Whig connections, but also mistress of widower

and philanderer Melbourne. Norton, although he protested undying love

for his childhood sweetheart, was in fact an appallingly violent and

abusive husband; they separated three times, but she returned for the

children's sake. Norton sued Melbourne, who had become Prime

Minister, in attempt to achieve a divorce. Melbourne was acquitted, but

many rash words were spoken by all parties and no-one emerged smelling

of roses. Dickens drew on the case - and the farcical way the lovers'

correspondence was treated in court - for his Pickwick Papers.

Norton then exonerated his wife in an attempt to win her back, and

thereafter denied her a divorce; further washing of dirty linen

followed, and she became a campaigner for women's matrimonial rights in

marriage - leading to the Custody of Infants Act 1839, the Matrimonial Causes Act 1857 and the Married Women's Property Act 1870. Nevertheless, he continued to hold his magistracy, now

sitting at Lambeth, until he retired because of 'failing health' in

1867, with pension, after 36 years on the bench.

The Hon George Chapple Norton

(1800-75): grandson of Baron Grantley, who was nicknamed 'Sir Bull-face

Double Fee' because of his success in geting government legal

appointments, and son of the well-paid Baron of the Exchequer in

Scotland, he attended Edinburgh University but does not appear to have

graduated. Through family connections, he became Tory MP for Guildford

1826-30, voting mainly with the party line. Appointed Recorder of

Guildford, his Whitechapel magistracy (with a salary of £1,000)

debarred him from standing again for Parliament. This post was fixed by

his wife Caroline [right, by George Hayer 1832], daughter of the playwright Sheridan, and herself a considerable

writer - with Lord Melbourne, the Home Secretary. Not only was

she from a family with Whig connections, but also mistress of widower

and philanderer Melbourne. Norton, although he protested undying love

for his childhood sweetheart, was in fact an appallingly violent and

abusive husband; they separated three times, but she returned for the

children's sake. Norton sued Melbourne, who had become Prime

Minister, in attempt to achieve a divorce. Melbourne was acquitted, but

many rash words were spoken by all parties and no-one emerged smelling

of roses. Dickens drew on the case - and the farcical way the lovers'

correspondence was treated in court - for his Pickwick Papers.

Norton then exonerated his wife in an attempt to win her back, and

thereafter denied her a divorce; further washing of dirty linen

followed, and she became a campaigner for women's matrimonial rights in

marriage - leading to the Custody of Infants Act 1839, the Matrimonial Causes Act 1857 and the Married Women's Property Act 1870. Nevertheless, he continued to hold his magistracy, now

sitting at Lambeth, until he retired because of 'failing health' in

1867, with pension, after 36 years on the bench. Sir Thomas

Henry (1807-76 - right):

an Irish Roman Catholic, graduate of Trinity College Dublin, called to

the Bar at the Middle Temple in 1829, and after working on the northern

circuit was appointed to Lambeth Street in 1840, transferring in 1846

to Bow

Street, where he became chief magistrate. He was a principal architect

of the 1862 Extradition Act, and was a government adviser on licensing (theatres and pubs), betting, and Sunday trading.

Sir Thomas

Henry (1807-76 - right):

an Irish Roman Catholic, graduate of Trinity College Dublin, called to

the Bar at the Middle Temple in 1829, and after working on the northern

circuit was appointed to Lambeth Street in 1840, transferring in 1846

to Bow

Street, where he became chief magistrate. He was a principal architect

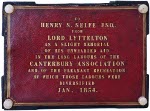

of the 1862 Extradition Act, and was a government adviser on licensing (theatres and pubs), betting, and Sunday trading. Selfe was active in the Canterbury Association, promoting settlement to New Zealand (where another son, James, went to live; another relative, Charles Henry Selfe Matthews (1873-1961), was a priest serving with the Bush Brotherhood in Australia in the early years of the next century). Right is a presentation casket from Lord Lyttleton of 1854. He

used his contacts and knowledge of the principal settlers to help the

colony get established. He became honorary London agent for the

Provincial Government, but resigned in 1866 because he felt compromised

by misinformation about a railway loan, whereupon he was given an

honorarium of £500 by the government, with which he bought a plot of

100 acres at Heathcote, travelling out to Canterbury with Lord

Lyttleton in 1866-67. He was a director of the London Board of the New

Zealand Trust and Loan Company. He had hoped to be appointed to a

judgeship there, and there is much correspondence on the matter, but Henry Barnes Gresson was appointed instead.

Selfe was active in the Canterbury Association, promoting settlement to New Zealand (where another son, James, went to live; another relative, Charles Henry Selfe Matthews (1873-1961), was a priest serving with the Bush Brotherhood in Australia in the early years of the next century). Right is a presentation casket from Lord Lyttleton of 1854. He

used his contacts and knowledge of the principal settlers to help the

colony get established. He became honorary London agent for the

Provincial Government, but resigned in 1866 because he felt compromised

by misinformation about a railway loan, whereupon he was given an

honorarium of £500 by the government, with which he bought a plot of

100 acres at Heathcote, travelling out to Canterbury with Lord

Lyttleton in 1866-67. He was a director of the London Board of the New

Zealand Trust and Loan Company. He had hoped to be appointed to a

judgeship there, and there is much correspondence on the matter, but Henry Barnes Gresson was appointed instead. William Partridge (1863-69)

William Partridge (1863-69) From 1860-88 he wrote regularly for Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine.

His articles criticizing Macaulay's views of Marlborough, the massacre

of Glencoe, the highlands of Scotland, Claverhouse, and William Penn,

were reprinted as The New Examen (1861). Other articles on a wide range

of topics, including Nelson, Byron, well-known legal cases, and art,

appeared as Paradoxes and Puzzles: Historical, Judicial,

and Literary (1874). He was also a skilful draughtsman, and his illustrations to Edward Fordham Flower's Bits and

Bearing-Reins (1875) helped to show the cruelty to horses caused by this method of harnessing [example right].

The Pagets moved in artistic circles, and Elizabeth's collection of

family papers (now in the National Archive) includes letters to and

from well-known artists of the day.

From 1860-88 he wrote regularly for Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine.

His articles criticizing Macaulay's views of Marlborough, the massacre

of Glencoe, the highlands of Scotland, Claverhouse, and William Penn,

were reprinted as The New Examen (1861). Other articles on a wide range

of topics, including Nelson, Byron, well-known legal cases, and art,

appeared as Paradoxes and Puzzles: Historical, Judicial,

and Literary (1874). He was also a skilful draughtsman, and his illustrations to Edward Fordham Flower's Bits and

Bearing-Reins (1875) helped to show the cruelty to horses caused by this method of harnessing [example right].

The Pagets moved in artistic circles, and Elizabeth's collection of

family papers (now in the National Archive) includes letters to and

from well-known artists of the day.| The

prisoner, who was attired in hat and feathers, a lace veil of fine

texture, a Paisley shawl worth at least four guineas, and a superb

flounced black silk dress said the unfortunate condition she was in was

all owing to the Underground Railway. Mr Paget: What do you mean? The Prisoner said she paid a visit to her brother and his wife yesterday at Paddington and proceeded there and back by the Underground Railway, which had such an effect upon her that sho became insensible. Mr Paget: You were intoxicated. Prisoner: Yes, I had one glass of gin, no more, after leaving the Underground Railway. I will never take any more. Mr Paget: What are you? Prisoner: A policeman's wife. He has been twenty years in the force. Oh, Sir, it is all owing to the Underground Railway [Laughter]. |

| George La Pierre, a seaman, came before Mr. Paget, at the Thames Police

Court, on Thursday, for redress under very singular circumstances. He

went out in the English ship Universe

to New York. One day he went on shore in New York with the third mate,

who got tipsy and made a noise. He was leading the third mate along

with the intention of returning to their ship when the Police

interfered, and took the third mate into custody and locked him up for

making a noise. At the same time several runners and crimps attacked

him and beat him, and having overpowered him took him to a house where

they kept him a close prisoner all night, and in the morning forced him

on board the American ship Caroline Nasmyth.

He was compelled to remain on board by the Captain and chief mate, to

whom he represented that he was the boatswain of the Universe, was

afflicted with a bad leg, and unable to do any hard work. The Captain

said he did not care about his leg, and that all he wanted was his

body; that he had paid men to bring him on board, and that he must work

on the voyage to England. He arrived in the Victoria Dock on Wednesday,

and asked for wages for his services. The Captain refused to pay him

anything, and he had now come on shore to seek redress and compensation

for a gross act of injustice and oppression. Mr. Paget asked the applicant if he had signed any articles of agreement on board the Caroline Nasmyth, to which he answered in the negative, and said he had no other clothes but what he stood upright in. He came across the Atlantic Ocean without a change of clothes and linen. In answer to further questions by the magistrate, the applicant said all his clothes were on board the Universe, which had arrived at Liverpool. His wife had applied for his chest, hammock, and clothing on board the Universe, at Liverpool, and the reply of the Captain was that he knew nothing about them. Mr. Paget could not help thinking it was a very hard case on the man. He was afraid he could not interfere in the matter. If the Caroline Nasmyth was an English ship he would grant a summons for wages. He had no jurisdiction over American ships. With regard to the clothes on board the Universe he would recommend La Pierre to write to his wife at Liverpool and direct her to apply to Mr. Raffles, the stipendiary magistrate there, who would render every possible assistance. The Applicant: What am I to do here? I have no means of living, and no money. Mr. Paget advised the seaman to wait on the American Consul and represent his grievances to him. The seaman then left, and at 5 o'clock returned and said the American Consul refused to give him any redress, and only laughed at him. The consul threatened to have him arrested and sent back to the Caroline Nasmyth again. Mr. Paget said that could not be done, and he would take care the sailor was not arrested or kidnapped in his own country. He directed Howland, a police constable, No. 89 H, who is attached to the court, to take charge of the seaman, to provide him with food and a lodging, and to make very particular inquiries into all the circumstances of the case, and report to him the result. The applicant then left with the officer. |

Born

in Hanley in 1828, son of Moses George Benson of Lutwyche Hall, near

Wenlock (the family home from the start of the 19th century - left), whose

grandfather Moses was a Liverpool merchant, probably involved in the

slave trade, and whose father Ralph was MP for Stafford. His

mother Charlotte Riou Browne was a

descendant,

several generations

back, of Mathieu Riou, member of the protestant congregation of

Vernoux in eastern France.

Ralph studied

at Christ Church, Oxford,

and was admitted to the Bar, practising in the Oxford circuit. He

stood unsuccessfully as a

Tory

candidate for the Wrekin Division of Shropshire,

and also for Reading..

Born

in Hanley in 1828, son of Moses George Benson of Lutwyche Hall, near

Wenlock (the family home from the start of the 19th century - left), whose

grandfather Moses was a Liverpool merchant, probably involved in the

slave trade, and whose father Ralph was MP for Stafford. His

mother Charlotte Riou Browne was a

descendant,

several generations

back, of Mathieu Riou, member of the protestant congregation of

Vernoux in eastern France.

Ralph studied

at Christ Church, Oxford,

and was admitted to the Bar, practising in the Oxford circuit. He

stood unsuccessfully as a

Tory

candidate for the Wrekin Division of Shropshire,

and also for Reading..

In 1867 he refused to make a conviction based on the evidence of a ten-year old girl, although it was given in a very clear and straightforward manner, and with an appearance of great truth, since it was uncorroborated, and a second girl who was present had not come forward, despite the case being twice adjourned; furthermore, he had before him the character witness of the incumbent of a large parish, who had known the prisoner five years, and spoke of him as a well conducted, respectable, and moral man. Recognising that his action might be regarded as controversial (because the evidence of a single witness was normally sufficient), he said he hoped he was not doing wrong in the step he was about to adopt. Punch commented favourably on this remark: The really worthy Magistrate may make up his mind on that point. He was not doing wrong in refusing to convict on evidence which, whether true or false, was insufficient. He was doing right. In so doing he certainly did what was, as aforesaid, a very extraordinary thing, but will be, let us hope, in good time an ordinary thing, as it will whenever Magistrates in general get accustomed invariably to weigh evidence by the standard of reason and justice. Mr Benson has shown them how to use the scales.

In

1869, according to the Daily News and The Times, Constable William

Smith was dismissed from the force and sentenced by Benson to a

month's hard labour for using excessive force in protecting a woman

abused by her husband - John Stuart Mill noted this case in

correspondence.Benson

was transferred to Southwark (working alongside William Partridge) on

the appointment of Sir Franklin Lushington.

In

1869, according to the Daily News and The Times, Constable William

Smith was dismissed from the force and sentenced by Benson to a

month's hard labour for using excessive force in protecting a woman

abused by her husband - John Stuart Mill noted this case in

correspondence.Benson

was transferred to Southwark (working alongside William Partridge) on

the appointment of Sir Franklin Lushington.

He

married Henrietta Cockerell in 1860 and they had three sons and two

daughters,

to one of whom, at St Peter Easthope in Shropshire (the local church of

Lutwyche Hall, rebuilt in Arts and Crafts style after a fire in 1928)),

there is a window in the chancel of 1933 [right] by the famous firm of Kempe (which closed the following year): In honour of Our Lord Jesus Christ, the King

of Martyrs, and of His Apostle St. Philip who suffered martyrdom on

the Cross, this window is dedicated as a memorial to Philippa Jessie,

daughter of Ralph Augustus Benson of Lutwyche, by George Reginald

Benson. A.D. mcmxxxiii.

He

was a member of Marylebone Cricket Club: his 'career' details are

here. He

contracted smallpox in 1871 but recovered, living until 1886 when he died in Marylebone.

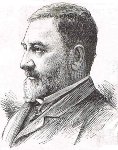

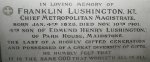

Sir Franklin Lushington (1869-90)

Franklin (1822-1901) was the fourth

son of the 13 children of the Hon Edmund Henry Lushington, who among

other judicial posts was puisne judge of the Court of Ceylon (and whose

father was a well-known barrister). There were other lawyers in the

family, but ironically his older brother Edmund (1811-93), who was given the

middle name 'Law', was not one of them - he became a Professor of Greek

and Rector of Glasgow University. Franklin was named for a

distinguished naval captain ancestor of the previous century. He was a

pupil of Thomas Arnold at Rugby - one of the last, along with the Dean

of Westminster, to survive into the 20th century. After Trinity College

Cambridge, where he held scholarships and was a medal-winner,

graduating in 1846. he was called to the Bar at the Inner Temple in

1853. A spell in the diplomatic service brought him an

appointment from 1855-58 to the Supreme Council of Justice of the Ionian Islands

which were under British rule from 1815-62 - Bulmer Lytton, Secretary

of State for the Colonies, appointed him; Sir George Bowen was the

Governor; and Gladstone was for a time the High Commissioner, who

recommended that rule of the islands should be returned to Greece. Like

other lawyers, he did not feel specifically called to 'serve' abroad,

and not keen to leave home, but

it is necessary to have some definite work to do in place of the

prospect of spending the best years of one's life at home doing little

or nothing - a prospect common to most pursuers of the English bar at

the present (1855, to Whiiliam Whewell).

In 1869 he became a metropolitan magistrate, with the Thames Police

Court as his first appointment, where he sat until 1890 (on a stipend

of £1500 a year), when he was transferred to Bow Street (the Central

Criminal Court), becoming chief magistrate - and knighted - in 1899

until his sudden death two years later. He was described as quiet and severe, and as fair and impartial; The Sketch said he would be remembered for his

capacity for giving the closest attention to every case, trivial as

some might be, and for a uniform kindliness towards all. [Right is his gravestone, at St Mary Boxley, near Maidstone - Park House was the family home.]

In 1869 he became a metropolitan magistrate, with the Thames Police

Court as his first appointment, where he sat until 1890 (on a stipend

of £1500 a year), when he was transferred to Bow Street (the Central

Criminal Court), becoming chief magistrate - and knighted - in 1899

until his sudden death two years later. He was described as quiet and severe, and as fair and impartial; The Sketch said he would be remembered for his

capacity for giving the closest attention to every case, trivial as

some might be, and for a uniform kindliness towards all. [Right is his gravestone, at St Mary Boxley, near Maidstone - Park House was the family home.]

An example of a 'trivial' case was a dispute in 1877 between members of a group known as the 'Social Trumps' - settle it among yourselves,

he told them. But he was involved in many high-profile criminal trials

- including, at the time of his death, the prosecution of Dr Frederick Edward Trangott Krause on charges of high treason and incitement to murder, in relation to the Boer War.

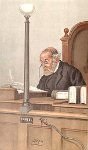

He was jealous of the reputation of the police: Sir Leslie 'Spy' Ward (the caricaturist of Vanity Fair - image left, 1899)

provided the strapline 'He Believes in the Police'. When evidence

conflicted, he almost invariably accepted the police version, once

remarking I have had occasion for

many years to listen closely to evidence given by ihe police concerning

the persons they are brought into contact with. As compared with, other

witnesses they are, in nine cases out of ten, least likely to have made

a mistake, for it is part of their duty to cultivate a habit of

observation. But there were occasions when he dealt harshly with police defaulters.

He was jealous of the reputation of the police: Sir Leslie 'Spy' Ward (the caricaturist of Vanity Fair - image left, 1899)

provided the strapline 'He Believes in the Police'. When evidence

conflicted, he almost invariably accepted the police version, once

remarking I have had occasion for

many years to listen closely to evidence given by ihe police concerning

the persons they are brought into contact with. As compared with, other

witnesses they are, in nine cases out of ten, least likely to have made

a mistake, for it is part of their duty to cultivate a habit of

observation. But there were occasions when he dealt harshly with police defaulters.

His

private life has been subject to some speculation. In 1848/49, when he was

in Malta (where his brother Henry was Government Secretary) he met Edward Lear [right];

they toured southern Greece together, and Lear developed an intense

passion for him, though wrote to his sister Anne in somewhat more guarded terms: My companion is

Mr. F. Lushington a very amiable & talented man – to travel with

who is a great advantage to me as well as a pleasure. When Lushington went to the Ionian Islands

Lear joined him, making his home in Corfu, remaining there for many

years (together with his servant Giorgio Kokali) as he toured the

Mediterranean. (An aside: in Cannes Lear met old Harrovian, and

forthright advocate of male intimacy, John Addington Symonds, for whose

daughter Janet he wrote The Owl and the Pussycat. Some say Symonds

was implicated in the non-preferment of Harrow's headmaster, brother of

the vicar of St Mark Whitechapel - more details here. Symonds was also a friend from student days of Judge Cluer

of Whitechapel County Court).

His

private life has been subject to some speculation. In 1848/49, when he was

in Malta (where his brother Henry was Government Secretary) he met Edward Lear [right];

they toured southern Greece together, and Lear developed an intense

passion for him, though wrote to his sister Anne in somewhat more guarded terms: My companion is

Mr. F. Lushington a very amiable & talented man – to travel with

who is a great advantage to me as well as a pleasure. When Lushington went to the Ionian Islands

Lear joined him, making his home in Corfu, remaining there for many

years (together with his servant Giorgio Kokali) as he toured the

Mediterranean. (An aside: in Cannes Lear met old Harrovian, and

forthright advocate of male intimacy, John Addington Symonds, for whose

daughter Janet he wrote The Owl and the Pussycat. Some say Symonds

was implicated in the non-preferment of Harrow's headmaster, brother of

the vicar of St Mark Whitechapel - more details here. Symonds was also a friend from student days of Judge Cluer

of Whitechapel County Court).

On Lear's last trip to England in 1880 he

stayed with the Lushingtons at their home at 33 Norfolk Square 9near Paddington Station), where he

put on an exhibition of his works. Lushington and others continued to

visit Lear at his Italian home in San Remo until his death in 1888, when Lushington wrote to Mrs Charles Street he has always

been the most charming & delightful of friends to me; & apart

from all his various qualities of genius, I have never known a man who

deserved more love for his goodness of heart & his determination to

do right; & I don’t think any human being knew him better than I

did. There never was a more generous or more unselfish soul. He

was the executor of Lear's estate - all his papers and paintings were

left to him, and the proceeds from the sale of Villa Emily, or Tennyson

[named for the poet's wife] in San Remo and its contents were left to

Franklin's eldest daughter Luoisa Gertrude. He

wrote the entry on Lear (and others) which appeared in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica.

On Lear's last trip to England in 1880 he

stayed with the Lushingtons at their home at 33 Norfolk Square 9near Paddington Station), where he

put on an exhibition of his works. Lushington and others continued to

visit Lear at his Italian home in San Remo until his death in 1888, when Lushington wrote to Mrs Charles Street he has always

been the most charming & delightful of friends to me; & apart

from all his various qualities of genius, I have never known a man who

deserved more love for his goodness of heart & his determination to

do right; & I don’t think any human being knew him better than I

did. There never was a more generous or more unselfish soul. He

was the executor of Lear's estate - all his papers and paintings were

left to him, and the proceeds from the sale of Villa Emily, or Tennyson

[named for the poet's wife] in San Remo and its contents were left to

Franklin's eldest daughter Luoisa Gertrude. He

wrote the entry on Lear (and others) which appeared in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica.

Was Lear's passion for Franklin Lushington ever reciprocated? Though

they remained friends for over forty years, the consensus is a fairly

firm 'no' - which was a source of torment to Lear, whose other

relationships were also fraught. Lushington had married Kate, a

clergyman's daughter, in 1862, and as noted above they had a family (their out-of-town

home was at Southborough, near Tunbridge Wells - in a house named

'Templechurch'). Yet he is listed in Keith Stern Queers in History: The Comprehensive Enclopedia of Historical Gays, Lesbians and Bisexuals (2013), with an inconclusive entry.

In 1855, at the time of the Crimean War, he published a slim book of verse Wagers of Battle, writen by himself and his brother Henry. Henry was a close friend of the poet Tennyson - who wrote of him Three men have I loved, and / Thou art the last of the three - and a member of the Cambridge Apostles.

He was a Fellow of Trinity College, called to the Bar but not in

regular practice because of delicate health; appointed by Lord Grey as

chief secretary of the government of Malta, he was engaged in many

issues - police policy, law reform, education, and internal relgious

and other conflicts; he took a keen interest in the revolutionary

movements of 1848 and was symathetic to the French Republic, Italian Risorgimento

and Hungarian nationalism. He fell ill after seven years there and died

in Paris in 1855, Franklin rushing from Corfu to be with him. The book was republished, with additions, in 1899. Here is an extract from one

of the later poems, of dubious poetic but undoubted patriotic merit:

| Prayers—for strength to defend the right, through drifts of doubt, In trouble and stress, Prayers—for wisdom to guide the helm—prayers for His grace to govern and bless: Thanks—for valour of daughter nations, happy to press where their mother strives, Eager to aid her, eager to shield her, loyally lending love and lives. Hail, Australia! welcome, Canada! Greater Britain all round the wave, Fight one fight and carry one banner, plant it firm on tyranny's grave. Weld our kinship Into Empire—Empire based on the one true plan, Freemen's rights and freemen's Justice broadening still between man and man. Honestly wrought for, fearlessly fought for, spreading o'er land and spread aver sea, Empire—born of a stern death-struggle, christened in blood of the brave and the free. |

Whitechapel County Court: Judges Manning, Riddell, Bacon, Cluer

James Manning - 1847-63

| The

paper of Prof. Hindley was a review of an essay on 'The English

Possessive Augment', by Serjeant James Manning of Oxford, Eng.,

published in the Transactions of the Philological Society (London

1864). Mr Manning holds that the Anglo-Saxon genitive was given up in

the 13th century, and its place supplied by of with the accusative; but that for the possessive relation, a special form was then introduced, such as 'father his book', 'mother his gown', 'children his

plaything', which gradually passed into 'father's book', 'mother's

gown', 'children's plaything'. Against the common view, which

identifies the s of our

possessive with that of the A.-S. genitive, he urges that the latter

was not applied to feminines and plurals, and that it was used for many

relations which are not expressed by our possessive. But Prof. Hadley

referred to examples of grammatical forms (as the s

of plural nouns in French and Spanish) extended to classes of words

that once excluded them, and of forms (as the Latin perfect indicative

active in all Romance languages) restricted in the range of meanings

that once belonged to them. He examined the constructions of our

possessive which Mr. Manning regards as inconsistent with its genitive

origin. In 'Cæsar's crossing the Rubicon' we have only the ordinary use

of a genitive to denote the subject of an action. In 'John and Walter's

house' the possessive s is added to 'John and Walter' taken as a complex whole; compare eth in 'three-and-twentieth'. The same explanation applies to 'King of England's crown': compare ism

in 'Church-of-England-ism'. In 'a servant of my brother's', Lowth

regarded 'brother's' as depending on 'servants' understood—an

explanation which fails for 'that wife of my brother's': it is better

to regard the genitive here as dependent on a general idea of

'belongings', 'that which belongs', the same idea which is evidently

understood in 'all mine is my brother's'. Positive arguments for his

own view Mr. Manning draws from the popular dialects of modern Germany,

and from the usage of Semi-Saxon and early English writers. But while

the common German says 'des Vaters sein Buch', he says 'der Mutter ihr Kleid': if our English possessive were of the same nature, we should have, not 'mother his gown' (according to Mr. M.'s theory) but 'mother her gown'. That the Gothic reflexive seins and the Latin reflexive suus mean her and their as well as his, proves, at most only a possibility that his]might be so used in place of her:

that it was actually and currently used in this way, there is no

sufficient reason for believing. In almost every instance where it

seems to be used, his refers to a word like wife, maiden, child, which in Anglo Saxon were neuter not feminine. Mr

Manning gives great prominence to a comparison between the two

manuscripts of Layamon's Brut. in the first of which, written about

1200 A.D., the genitive expressed by his is rarely, if ever, met

with; while in the second, written perhaps sixty years later, such

forms are of common occurrence. Even here, in examining amining the

first 9000 lines of the poem, Prof. Hadley had found, from common

nouns, about eighty genitives with inflectional s, and only two

expressed by his; from proper names of place, thirteen with

inflectional s, and two expressed by his; even from proper names of

persons, where the genitives expressed by his are numerous there are

nearly as many with inflectional s, and the two forms are and freely

and capriciously interchanged. In the Ormulum, written bv a very

careful scribe at a time not earlier than the second text of Layamon,

the form with his is never once used. And although this form is often

seen in old English writings, and to the beginning of the last century,

yet it appears, on the whole, as an occasional—and, seemingly, a merely

orthographic—variation of the inflectional genitive—a variation

suggested by a false, though plausible, etymology, and favored [sic] by

general confusion of early English orthography. In connection with this paper, Prof. Whitney referred to another and wholly account of our possessive suffix, given in the Reader for Sept. 24, 1864, in the form of a critique upon Mr. Manning's essay, under the signature of Th. G. [Prof. Goldstücker}. Its author accepts as satisfactory Mr. Manning's disproof of the relationship between the suffix in question and the ancient genitive-ending, but regards the former as a mere connecting-link between the name of the possessor and the thing possessed, binding them together into a kind of compound. Prof. Whitney combated this view, as in a high degree far-fetched and fanciful, and attempted to overthrow the arguments by which it was supported. There is no more difficulty, he claimed, in supposing the retention of a true synthetic form along with the elaboration of an analytic substitute for it in the case of John's son and the son of John, than in the case of I loved and I did love. The position of the possessive before the thing possessed is no more fixed in the case of a noun than in that of a pronoun, as his or her, which no one would think of denying to be ancient genitives. And the s in such German words as Hilfstruppen, Liebesgabe is really a genitive-ending, or introduced after the analogy of such; precisely as is the s of nachts, formed after the analogy of abends, morgens, etc. |

Sir Walter Buchanan Riddell - (1863-??)

Sir Walter Buchanan Riddell - (1863-??)

The family home

by then was at (all or part of?) The Palace, Maidstone - originally, in

the 14th century, a palace of the Archbishop of Canterbury (and nowadays a popular wedding venue). A younger

brother, Canon John Charles Buchanan Riddell, was Rector of nearby

Harrietsham. Sir Walter was appointed Recorder of Maidstone &

Tenterden in 1846 (in the room of [= succeeding] R G Temple, deceased)

and continued to hold this office alongside others until 1868, when the

Mayor of Maidstone moved a vote of thanks for his contribution to

the town.

The family home

by then was at (all or part of?) The Palace, Maidstone - originally, in

the 14th century, a palace of the Archbishop of Canterbury (and nowadays a popular wedding venue). A younger

brother, Canon John Charles Buchanan Riddell, was Rector of nearby

Harrietsham. Sir Walter was appointed Recorder of Maidstone &

Tenterden in 1846 (in the room of [= succeeding] R G Temple, deceased)

and continued to hold this office alongside others until 1868, when the

Mayor of Maidstone moved a vote of thanks for his contribution to

the town. | On Tuesday night last, Dec. 26, 1843, Sir Walter Riddell, Bart., was returning to his residence at the Palace, Maidstone, when, on passing

the mill-head of Messrs. Mercer and Parton's mills, the honourable

baronet met a man and woman, and immediately afterwards heard a splash

in the water and a cry of distress. Sir Walter hastened to the spot,

and seeing something on the surface of the water, which is at this spot

about six feet deep, and runs with a rapid current under a low archway

of the mill, without hesitation plunged in with all his clothes on, and

succeeded in saving from a watery grave the woman whom he had passed

just before, and who, by some means or other not clearly ascertained,

had got into this most dangerous situation, from which, without the

honourable baronet's aid, there is no probability that she could have

been rescued. The difficulty of effecting a landing from a deep piece

of water on a perpendicular bricked

embankment is obvious; and had not the man assisted in getting her on

the bank, it is not likely that Sir Walter could have accomplished his

humane object, if indeed he had himself escaped a watery grave. (Signed) Edw. Pickard Hall, Maidstone. N.B. The Secretary of the Institution is indebted to Sir John Croft, who resides at Millgate, near Maidstone, for the following additional particulars: — Sir Walter Riddell, on rescuing the woman, carried her towards a public-house, upwards of two hundred yards. His strength failing him, he obtained assistance, and had her conveyed to the Man of Kent, where he remained in his wet clothes, affording every means for her recovery, for an hour and a half. The night was intensely dark, and nothing but the most prompt and determined energy on his part could have saved him from being swept by the rapid mill-race through the low arch with the woman whose life he saved. |

| On Monday

evening a crowded public meeting of freeholders and other electors of

West Kent was held at the Lecture Hall, Woolwich, for the purpose of

hearing an address from C. W. Martin, Esq, explanatory of his political

principles as a candidate for their suffrages. The chair was occupied

by F. Bennoch, Esq., and Mr. Martin, at some length, avowed himself an

advocate of an extension of the suffrage, a repeal of the income-tax, a

total and unconditional repeal of Church-rates, and of reforms in the

army, navy, and civil service. In reply to questions, Mr. Martin said

he was opposed to the ballot, and in favour of a continuance of the

Maynooth grant. Several electors expressed themselves strongly in

favour of the ballot, and ultimately a resolution was unanimously

adopted, pledging the meeting to support Mr. Martin at the ensuing

election. A similar meeting has been held at Greenwich, at which Mr. Whitehurst and other members of the Ballot Society were present, but not being electors could not be heard. A numerous meeting of the supporters of Sir W. B. Riddell, the Conservative candidate, was held at Maidstone, on Thursday afternoon, at which Viscount Holmerdale presided. |

Judge Riddell

died in 1892 at Henham Hall, Suffolk [right] - another stately pile (at one

time among the 'top five' landed estates): the redbrick Tudor house was

rebuilt in the 1790s after a major fire, and given a Victorian

'makeover' by Edward Middleton Barry (third son of Sir Charles Barry); it was demolished in 1950. See further

Alan Mackley 'The Construction of Henham Hall' in vol 6 of the Journal of the

Georgian Group (1996).

Judge Riddell

died in 1892 at Henham Hall, Suffolk [right] - another stately pile (at one

time among the 'top five' landed estates): the redbrick Tudor house was

rebuilt in the 1790s after a major fire, and given a Victorian

'makeover' by Edward Middleton Barry (third son of Sir Charles Barry); it was demolished in 1950. See further

Alan Mackley 'The Construction of Henham Hall' in vol 6 of the Journal of the

Georgian Group (1996).Back to Policing and Courts