Ritualism Riots

This page has many links to transcriptions of documents from the time, from newspapers and journals.

| See here

for details and pictures of the Archbishop

of Canterbury's visit to the church on 20 January 2010 to mark

the 150th anniversary of the Riots. See here for the texts of short papers given by three historians (Prof John Wolffe of the Open University and 'Building on History' project; Dr Dominic Janes of Birkbeck College; and the Revd Dr Jeremy Morris, then Dean and now Master of Trinity Hall Cambridge (after a spell as Dean of King's College Cambridge), at St George-in-the-East on 18 March 2010, and reproduced with their permission, for which we express our thanks. |

In

these days of liturgical diversity, with the general public

largely indifferent about what goes on in churches, it's strange to

think

that 150 years ago, because of changes to the style of worship,

thousands of people stormed a church Sunday by Sunday for several

months, bringing in their dogs, lighting their pipes and attempting

to set fire to the furniture, throwing their caps in the air,

heckling and jeering and catcalling throughout the sermon and singing

rival songs during the hymns. Rule Britannia and

God save the Queen were

the favourites, though 'nigger ditties' were also sung. Dean Stanley

(of Westminster) attended on one occasion and, having no ear for

music, nor eye for what was going on, is said to have pronounced the

hymn-singing to

be 'most hearty'. He also related how a woman near him, when the

preacher emerged from the vestry in gown rather than surplice [see

below], exclaimed Thank God! It's black.) There were riots outside the church too, so that

the Rector needed a police escort to escape from a side door back

into the Rectory.

In

these days of liturgical diversity, with the general public

largely indifferent about what goes on in churches, it's strange to

think

that 150 years ago, because of changes to the style of worship,

thousands of people stormed a church Sunday by Sunday for several

months, bringing in their dogs, lighting their pipes and attempting

to set fire to the furniture, throwing their caps in the air,

heckling and jeering and catcalling throughout the sermon and singing

rival songs during the hymns. Rule Britannia and

God save the Queen were

the favourites, though 'nigger ditties' were also sung. Dean Stanley

(of Westminster) attended on one occasion and, having no ear for

music, nor eye for what was going on, is said to have pronounced the

hymn-singing to

be 'most hearty'. He also related how a woman near him, when the

preacher emerged from the vestry in gown rather than surplice [see

below], exclaimed Thank God! It's black.) There were riots outside the church too, so that

the Rector needed a police escort to escape from a side door back

into the Rectory.All

this is what happened

at St George-in-the-East between May 1859 and July 1860. Questions

were asked in both Houses of Parliament, where there was little

support for the Rector and his pleas for more effective protection.

Indeed, because of the actions of the Vestry it was members of the

clergy and their friends, rather than the rioters, who were prosecuted.

Bryan

King

(1811-95) had

been a Fellow of Brasenose College Oxford, where after initial

suspicion of Tractarian teachers he was won over by their dignified

response in the face of hostility; Dr Pusey's sermons made a profound

impression on him. In 1837 he was appointed by Bishop Blomfield to

the perpetual curacy of St John, Bethnal Green, where he was also

joint secretary of the Bethnal Green Churches Fund. Unlike his

absentee cousin Joshua King, Rector of the neighbouring parish of St

Matthew, who left his parish in the care of his curate (Blomfield

tried in vain for twenty years to get rid of him - see here for more on non-resident clergy), Bryan King was a

dedicated and energetic parish priest, and in 1842 his college

appointed him to St George-in-the-East. Before he began his work, he

took an extended holiday with a friend, travelling to Norway on a

lobster smack, and then got married!

Bryan

King

(1811-95) had

been a Fellow of Brasenose College Oxford, where after initial

suspicion of Tractarian teachers he was won over by their dignified

response in the face of hostility; Dr Pusey's sermons made a profound

impression on him. In 1837 he was appointed by Bishop Blomfield to

the perpetual curacy of St John, Bethnal Green, where he was also

joint secretary of the Bethnal Green Churches Fund. Unlike his

absentee cousin Joshua King, Rector of the neighbouring parish of St

Matthew, who left his parish in the care of his curate (Blomfield

tried in vain for twenty years to get rid of him - see here for more on non-resident clergy), Bryan King was a

dedicated and energetic parish priest, and in 1842 his college

appointed him to St George-in-the-East. Before he began his work, he

took an extended holiday with a friend, travelling to Norway on a

lobster smack, and then got married!  He

found much to be done

at St George's after the inactivity of Dr Farington, and struggled

with the Vestry, who appointed dissenters and non-churchmen as

wardens (as explained here). He spurned the decanters of port

and sherry in the 'Rector's

cupboard' with which they expected to be plied before and after

service. (However, we should note that in 1836 the vestry had passed a

resolution controlling the excessive use of church funds for lavish

parish outings - details here.) Over time he increased the number of weekly services from 4 to

54. Some members of the congregation welcomed his ministry, but

others regarded him with suspicion. Conflict erupted in 1845 with a

'Requisition'

to the churchwardens, resulting in a stormy public vestry meeting on 18

March, chaired by Thomas Liquorish, the senior warden, with a

series of resolutions calling for a return to the previous style of

worship or his resignation [text and ensuing correspondence left]. The Times reported the meeting, noting with approval the remarks of one Mr Baddeley; here is a later account of its stance:

He

found much to be done

at St George's after the inactivity of Dr Farington, and struggled

with the Vestry, who appointed dissenters and non-churchmen as

wardens (as explained here). He spurned the decanters of port

and sherry in the 'Rector's

cupboard' with which they expected to be plied before and after

service. (However, we should note that in 1836 the vestry had passed a

resolution controlling the excessive use of church funds for lavish

parish outings - details here.) Over time he increased the number of weekly services from 4 to

54. Some members of the congregation welcomed his ministry, but

others regarded him with suspicion. Conflict erupted in 1845 with a

'Requisition'

to the churchwardens, resulting in a stormy public vestry meeting on 18

March, chaired by Thomas Liquorish, the senior warden, with a

series of resolutions calling for a return to the previous style of

worship or his resignation [text and ensuing correspondence left]. The Times reported the meeting, noting with approval the remarks of one Mr Baddeley; here is a later account of its stance:

| It was lamentable that a parish consisting of upwards of 13,000 souls

should be disturbed to its centre at the will of one individual, who

at his mere pleasure disturbed and deranged the beautiful and solemn

ceremonial of church service which had been handed town to us unchanged

for more than two centuries. These were not the days to trifle with the

laity. Men could not not be dragooned into a belief or compelled to a

ceremonial. Fortunately there was an organ of incalculable power and

extent to preserve and support the creed of their forefathers: the Times

was that powerful organ ... Their Rev. Rector talked of peace while he

was at the very time fomenting discord by introducing a Jim Crow sort

of buffoonery into the peculiarly solemn and impressive decencies of

our simple and affecting church service. Until this innovation was

palmed upon them there was not a more happy or united parish in the

whole kingdom than theirs [ a claim hardly borne out by the evidence of the parish's previous history!] The reporter added Several old parishioners, some of whom were affected even to tears, came forward to protest against practices which drove them from the church where their fathers had worshipped, and where healing memories of holy things soothed, while they sanctified, their Sabbath visits. All this, they said, was changed by the practice of their rector. The son passed by the grave of his father; the widower, of his wife; the mother, of her child,― to seek in some remote and unaccustomed house of worship that spiritual sustenance which the novel practices of their new rector had rendered unacceptable at his hands. [All the tricks of modern 'victim journalism' are on display in this paragraph!] |

| We, the churchwardens of the above parish, respectfully submit the following presentment: That the parish church, which is capable of containing upwards of 1,200 persons, has been for some time past comparatively deserted, and that on Sunday morning last, the 24 of May inst., the number who attended divine service in that edifice, exclusive of children, consisted of 113 persons only, and on several previous Sundays a much less number. That the greatest dissatisfaction prevails in that parish, and that we are without the requisite funds to pay the servants of the church and other customary expenses, and without the slightest prospect, until the removal of the present rector shall take place, of obtaining the sanction of the parishioners to the levying of a church-rate. |

In due course he resolved to make further enhancements to the plain style of worship, with the support of colleagues who had come, at his initiative, to staff the mission. They were generally more 'extreme' in their views: correspondence between Charles Lowder and Bryan King shows the former writing at great length, making high-handed and pernickety demands, to which the latter replied in a measured and gentlemanly way, conceding on personal matters but being firm on ecclesiastical principles.

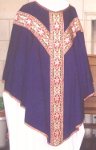

The

features that he

introduced were all things things that are regarded as quite normal

in most parish churches today: having lighted candles on a vested

altar, a robed choir singing psalms and responses (established in

1846), and

preaching

in a surplice rather than a black gown. The latter was, he believed,

in obedience to the Bishop Blomfield's own charge to his clergy to

observe the rubrics of the Prayer Book more carefully! (This had led

to the so-called 'surplice riots' elsewhere.) He scrupulously

followed the services of that book; the days when 'advanced' clergy

elsewhere incorporated Roman Catholic texts came later. In 1857 he was

given white and green silk

chasubles for

the Holy Communion, and after some initial hesitation he wore them,

until

stopped by the bishop. (These and other of his vestments were later

taken for use in New Zealand - see

below.) Right is the interior as shown in the Illustrated London News of 3 March 1860. The commentary, having declared the church a gloomy old-fashioned piece of architecture, and its windows very indifferently painted, draws attention to the

decoration so much complained of lately, and which is certainly quite

at variance with the character of the architecture of the church - namely, the large plain cross which King hung behind the altar during Lent, with drapery around the apse!

The

features that he

introduced were all things things that are regarded as quite normal

in most parish churches today: having lighted candles on a vested

altar, a robed choir singing psalms and responses (established in

1846), and

preaching

in a surplice rather than a black gown. The latter was, he believed,

in obedience to the Bishop Blomfield's own charge to his clergy to

observe the rubrics of the Prayer Book more carefully! (This had led

to the so-called 'surplice riots' elsewhere.) He scrupulously

followed the services of that book; the days when 'advanced' clergy

elsewhere incorporated Roman Catholic texts came later. In 1857 he was

given white and green silk

chasubles for

the Holy Communion, and after some initial hesitation he wore them,

until

stopped by the bishop. (These and other of his vestments were later

taken for use in New Zealand - see

below.) Right is the interior as shown in the Illustrated London News of 3 March 1860. The commentary, having declared the church a gloomy old-fashioned piece of architecture, and its windows very indifferently painted, draws attention to the

decoration so much complained of lately, and which is certainly quite

at variance with the character of the architecture of the church - namely, the large plain cross which King hung behind the altar during Lent, with drapery around the apse!

But there were several factors that inflamed passions, drawing churchmen to protest out of conviction and non-churchmen to join in for a piece of the action. Some of these have been explored in Own Chadwick's classic two-volume work The Victorian Church (A & C Black) and more recently by David Kent of the University of New England, Armidale NSW in High Church Rituals and Rituals of Protest: the 'Riots' at St George-in-the-East, 1859-60 (The London Journal vol.32.3, July 2007, pages 145-166).

Pope

Pius IX had restored the English

Roman Catholic

hierarchy in 1850, which continued to

arouse strong opposition from Protestant groups; 'no Popery' was a

potent cry, and remained so for many years. Unless you desist from your hellish and popish practice, wrote an anonymous correspondent, I shall take foul means to prevent [sic] you doing so. (Anti-popery was not, of course, new: right is a crude anti-popery ballad of 1827 - printed by Bishop at 6 Denmark Street, in the parish.)

Pope

Pius IX had restored the English

Roman Catholic

hierarchy in 1850, which continued to

arouse strong opposition from Protestant groups; 'no Popery' was a

potent cry, and remained so for many years. Unless you desist from your hellish and popish practice, wrote an anonymous correspondent, I shall take foul means to prevent [sic] you doing so. (Anti-popery was not, of course, new: right is a crude anti-popery ballad of 1827 - printed by Bishop at 6 Denmark Street, in the parish.) The

main emerging centres of 'advanced' worship were new, purpose-built district

churches which gathered like-minded congregations; by contrast, St

George-in-the-East was a long-established

parish church with a more miscellaneous congregation, where the traditions were changed - a point developed here (as part of his argument against the creation of district churches in large parishes) by

Harry Jones, Bryan King's successor, with which Owen Chadwick broadly

concurs. It's also worth noting that within the parish were two

places of worship that in King's time represented rather different

traditions - Trinity Episcopal Chapel and St Matthew Pell Street; furthermore, there was little rioting at the more 'extreme' mission chapel in Wellclose Square, though there is one illustration of this [right].

The

main emerging centres of 'advanced' worship were new, purpose-built district

churches which gathered like-minded congregations; by contrast, St

George-in-the-East was a long-established

parish church with a more miscellaneous congregation, where the traditions were changed - a point developed here (as part of his argument against the creation of district churches in large parishes) by

Harry Jones, Bryan King's successor, with which Owen Chadwick broadly

concurs. It's also worth noting that within the parish were two

places of worship that in King's time represented rather different

traditions - Trinity Episcopal Chapel and St Matthew Pell Street; furthermore, there was little rioting at the more 'extreme' mission chapel in Wellclose Square, though there is one illustration of this [right].

The

flashpoint was the

nomination in 1859 of the Rev Hugh

Allen [right] as

Afternoon Lecturer, by

Blomfield's successor Bishop Archibald

Campbell Tait. Was this provocative, or blindness

to the sensitivities (Tait was a Scots Presbyterian who dismissed

ritual as 'tomfoolery')? King protested, but the Vestry confirmed the

appointment on 31 March and Allen was licensed on 17 May. He was a

noted Protestant preacher, a supporter of Spurgeon and the building

of his Tabernacle, and had been working in the adjacent parish of

Whitechapel.

The

flashpoint was the

nomination in 1859 of the Rev Hugh

Allen [right] as

Afternoon Lecturer, by

Blomfield's successor Bishop Archibald

Campbell Tait. Was this provocative, or blindness

to the sensitivities (Tait was a Scots Presbyterian who dismissed

ritual as 'tomfoolery')? King protested, but the Vestry confirmed the

appointment on 31 March and Allen was licensed on 17 May. He was a

noted Protestant preacher, a supporter of Spurgeon and the building

of his Tabernacle, and had been working in the adjacent parish of

Whitechapel.

His great-great-great-nephew, the Australian tennis writer Alan Trengove, includes a chapter about Hugh Allen and other family members in Saints and Sinners - and how they made me (2008).

According to the Act creating the post, as Lecturer he should be admitted by the Rector to have the use of the pulpit from time to time. The stage was set for conflict.

This

is the sequence of

events as recorded by King himself, in the Book of Minister's

Signatures kept in church (with additional comments and other events in

grey italic). See here

for a sequence of contemporary press cuttings for this period, mostly

from the Illustrated

London News.

|

22 May 1859: The Lecturer, Rev Hugh Allen, said the Litany and preached at 3.40pm, against the wish of the Rector, Mr Burn [curate] protesting. Great disturbance in the Church. Allen brandished his licence from the pulpit, to cries of 'Bravo, Allen!' Hearing of this, the Bishop asked him not to preach again until the Rector's rights were resolved, but Allen ignored this. 29 May: Litany stopped by a riot in Church. 12 June (Whitsunday): In consequence of the scandalous outrages committed in the Church during Divine Service during the last three Sundays and especially on 5 June, and on the refusal of the police authorities to act in the Church at the insistence of the Churchwardens, the Church was closed by the Rector, and, excepting the Celebration at 8am (followed immediately by Mattins) and a private celebration of Evensong at 5pm, the usual services were not celebrated. B.K. 26 June: On this day the Lecturer conducted a service at 2¼pm, the Rector having appointed that time after trial in the Court of Queen's Bench, 16 June 1859, but the presence of a crowd remaining in the Church, who had taken possession of the choir stalls, until 4¼pm, prevented the Litany being said as usual at 4pm. The timing was a concession by King, who in court had originally offered 5pm. According to the East London Observer, "the preacher did not forget that he stood in the pulpit of a Puseyite rector, and was appointed in antagonism to him. He found occasion, therefore, to dwell repeatedly, and in a marked manner, on disputed doctrines, and pomp and ceremony, troupes of choristers, and ritualism, as being opposed to the everlasting Gospel." On 14 August protesters took possession of the choir stalls, and interrupted the singing of the Litany with hisses and shouts; the officiant (Rev W.P. Burn) had a fit and collapsed, and the crowd jeered "It is a judgement of God against him – now down with Bryan King!" After the service, they went after the choirboys and a scuffle in the baptistery ensued. The wardens prosecuted a man who attempted to defend the choirboys, paying the legal expenses of both him and his assailant. 18 September: Litany could not be said; Rev A.H. Mackonochie, with great difficulty, rescued by five policemen from the violence of the mob in Church. 25 September: At the insistence of the Rector, the Bishop issued an order upon the Churchwardens for the closing of the Church – on this day and until further orders.....The Bishop offered his mediation between the Rector and Churchwardens – which the Rector accepted on the two points on which his lordship's interference had been invoked on behalf of the Vestry in the Vestry Clerk's letter of 2 September, i.e. - the time for the afternoon (Lecturer's) Service and the use of unaccustomed Vestments in the Church....The Bishop desired the Rector to discontinue the use of the Eucharistic Vestments and coloured stoles, and arranged that the Lecturer's Service should take place at 3½pm, so that the Litany might precede it. Behind this lay protracted correspondence between King and the Bishop, described as 'arbitration with a vengeance'. The Vestry continued to opposed King, but supportive members of the congregation plus other friends (including the Rectors of Stepney and Poplar) had formed the St George's Church Defence Association. On 1 October, Dickens' All The Year Round

published a tongue-in-cheek 'eye witness' account, which is interesting

for its concluding description of a 'debate' in the street after

the service: read it here. John Peterson was charged with disturbing the congregations at St George-in-the-East and the mission chapel in Wellclose Square. 6 November [the date when the church was re-opened]: The Morning Service was celebrated with very slight interruptions – before and after the Sermon. The Litany was seriously interrupted, at ¼ 3pm, the choir stalls having been taken possession of by a crowd; and in consequence of a threatening crowd assembled at the Church gates before 6½pm, Evening Service at 7pm was not attempted. At the instance of the Bishop and the Rector, the Secretary of State for the Home Department required the attendance of the police in the Church on Sunday. 13

November: The

Morning

Service was celebrated with considerable interruptions, the Litany

with slight interruptions, and the Evening Service (densely crowded)

was much interrupted, notwithstanding the presence of the police at

all the services. Police

support was then suddenly withdrawn – perhaps because of the

appointment of Hugh Allen to St George, Southwark – despite

King's

pleas to the Home Secretary and Police Commissioner for a gradual

withdrawal. Throughout this period the only prosecutions were of the

clergy and others for attempting to prevent protestors entering the

church – including Lowder, who was fined 2s. on 8 December.

(King

himself was fined 5s. for an alleged assault on 8 March 1860.)

The Spectator of 26 November reported that William Cornwallis, a King supporter, was brought to court for claiming a free seat and insulting the churchwarden, in consequence of his 'over-zeal for the choral service' and ill state of health; he was discharged after making an 'ample apology' to Mr Churchwarden Thompson. 29 January 1860: Morning Service and Litany were comparatively quiet, the Evening service unparalleled for its riot and violence, hassocks &c thrown from the galleries, and the altar with difficulty saved from attack after service. At the instance of the Rector the Church was cleared by the police, Mr Burn violently assaulted in Churchyard, and his hat torn in pieces. 29 January and 5 February were the climax of the riots. The Home Secretary (Sir George Lewis) was questioned in the House of Commons on 30 January (see Hansard record - which includes a claim that nonconformist worshippers now outnumbered those in the Church of England). There were detailed reports in The Times and other papers – here is an account from the Eastern Times of 5 February. The secular and church press was generally hostile to Bryan King, while asking why more was not being done to stop the disturbances, and calling on the Bishop to 'do his duty'. A few protesters were prosecuted for offences outside the church – including Daniel Stocker, a member of St Paul Dock Street, who was fined 40s. for being drunk and disorderly in a public thoroughfare and insulting the Rector (see his letter here). Some prosecutions were dropped on the promise of good behaviour in the future. Press coverage provoked further questions to the Home Secretary in the House of Commons, on 6 February and 10 February. Bryan King's peition for relief was presented in the House of Lords by Lord Brougham on 10 February. In March, in collusion with the Vestry, Tait ordered the removal of the choir seats and various altar hangings. Attacks continued – in March Frederick Stutfield, a choirman and stauch supporter of King, was assaulted, and in April a choirboy was struck on the head and carried out senseless. There was further debate in the House of Lords on 22 May, with the Bishop of London temporising, seeing no way forward, since changing the services, however desirable, would now be seen as condoning the actions of the mob. Henry Phillpotts, the elderly Bishop of Exeter, spoke in support of Bryan King, to whom he wrote sympathetically on two occasions. June 17: Morning Service was scarcely interrupted at all, few leaving at the beginning of the sermon, though Evening Service was interrupted by most violently shouting of responses, coughing &c. On

29 June in the House of

Commons

the Home Secretary (Sir George Lewis) was asked to comment, and said

that interruptions to the service were not matters for the police, but

that otherwise everything possible had been done to contain the

situation: see Hansard

report.

July

22: Rosier was

convicted in the penalty of £3 in the Thames Police Court, 19

July.

Morning Service entirely free from disturbance. Evening Service

undisturbed by readers and altogether much less disturbed than for a

long period. This

conviction was the first under the 1860 Ecclesiastical

Courts Jurisdiction Act,

which had received the royal assent on 3 July, giving the secular

courts power to deal with 'brawling' in and around churches. The

summons against Rosier was taken out by the new curate, Thomas Dove - here

is a report

of the trial; he was sentenced to three weeks in the House of

Correction. (Rosier was previously in court in October 1859 but the

charge had been withdrawn by the magistrate; in December 1859 Bryan

King had obtained an order from the Consistory Court against him.)

The second summons was against Joseph Rowe in September 1860 - The Times' account is here. This is King's last entry, for his health had broken down. He published an extended 'letter of remonstrance' to the Bishop of London, under the title Sacrilege and its Encouragement, which you can read here. An agreement was made to take a year's leave of absence, with Mr Hansard (later Rector of St Matthew Bethnal Green) licensed to take services. |

King left at the end of July (early in the morning, to avoid a brass band the opposition had hired to accompany him to the station), and he went to Bruges to recuperate. He and Mary stayed at 33 Places des Orientales, and at the English Chapel there on St Andrew's Day 1860 he baptized their daughter Beatrice Henrietta Pierrepoint (later recording the details in St George's baptismal register).

Although undertakings had been made not to make

alterations to the services, the Bishop failed to honour these, and

as a result Mr Hansard left. Bryan King refused to have anything to

do with the appointment of another curate-in-charge - see here for more

details.

Although undertakings had been made not to make

alterations to the services, the Bishop failed to honour these, and

as a result Mr Hansard left. Bryan King refused to have anything to

do with the appointment of another curate-in-charge - see here for more

details.

It

was not until 1863,

when his health had recovered, that a new post was found for him. He

exchanged livings with John Lockhart Ross, a college friend of Bishop

Tait, and became Vicar of Avebury in Wiltshire, retiring in 1894 (by

which time he was almost totally deaf - his curate son conducted the

services) and dying the following year [right in his later years].

Much

has been written

about the role of Bishop Tait [left - he

became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1868, until his death in 1882; Tait

Street, where there was a parish mission house, was named after him, in

recognition of his visit during the cholera epidemic.] Could he, and should he, have

done

more despite his instinctive disapproval? And why the police were

not able to act more decisively? The short answer is that

the public mood was against Bryan King. As one Protestant commentator

put it, He might save

himself a deal of trouble and vexation by sitting down, as others do,

to eat his pudding in peace (P.W. Parfitt, in The Pathfinder

3

December 1859) - but that was not his way. He persisted, responding to

his adversaries with remarkable charity. For this, he received

much positive support - some of it from surprising

quarters.

Much

has been written

about the role of Bishop Tait [left - he

became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1868, until his death in 1882; Tait

Street, where there was a parish mission house, was named after him, in

recognition of his visit during the cholera epidemic.] Could he, and should he, have

done

more despite his instinctive disapproval? And why the police were

not able to act more decisively? The short answer is that

the public mood was against Bryan King. As one Protestant commentator

put it, He might save

himself a deal of trouble and vexation by sitting down, as others do,

to eat his pudding in peace (P.W. Parfitt, in The Pathfinder

3

December 1859) - but that was not his way. He persisted, responding to

his adversaries with remarkable charity. For this, he received

much positive support - some of it from surprising

quarters.

The local, national and church press were almost

universally hostile to King. The Church Times,

which was to give stauch support to the ritualist and high church

cause, had not

yet been established; but its founder G.J. Palmer was actively involved

in the riots. As his great-grandson Bernard Palmer wrote in Gadfly for God (Hodder

& Stoughton, 1989), At

various periods he was to attend regularly at other budding centres of

Anglo-Catholic worship. . . George was prepared to be as militant a

churchman as any opponent. He won his spurs, in fact, as one of the

band of young laymen who, Sunday by Sunday, stood round the altar of St

George's-in-the-East, Whitechapel, to protect it from profanation by

Protestant-inspired mobs during the anti-ritual riots of 1859-60. The

Church Times

obituary of 1895, describing him as a man to whom the English

Church owes a deep debt of gratitude, is here.

Some

years later, King's son-in-law William

Crouch wrote a full, and sympathetic, account of King's life: Bryan

King and the Riots at St George's in the East (Methuen 1904),

which you can read online here.

A more recent scholarly work is Dominic Janes Victorian Reformation: The

Fight over Idolatry in the Church of England, 1840-1860 (OUP

2009). The most judicious, and enjoyable, brief account remains that of

the late great Owen Chadwick in The Victorian Church

(OUP 1966, & subsequent editions), vol 1 pages 495-501], which

you can read here.

Based on the work of his research students, and with many magisterial

touches, he sets the complex tale in its wider ecclesiastical and

social context rather than taking sides.

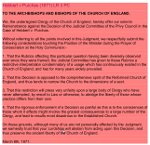

As

for St George-in-the-East: although some of King's 'innovations'

continued under his successors, particularly Harry Jones, they fairly

soon became less controversial, and the parish played little part in

the next phase of ritualism controversies, which concerned fresh

matters such as the 'eastward position' for the celebration of holy

communion, the use of vestments, wafer bread, the 'mixed chalice' (the

ceremonial adding of water to the wine), incense and processional

lights and other similar details. By 1871, 5,000 clergy - including

many from the East End were to sign a Remonstrance [right] to the Archbishops and Bishops protesting against the involvement of

the Privy Council in pronouncing on such matters in the case of Hebbert

v. Purchas,

overturning aspects of the judgement of a lower court in Elphinstone v.

Purchas. Copies of this document are pinned into the registers of

several of our and other local churches. In the 1880s, mosaics which would

have undoubtedly fuelled the protests in King's time were installed

without fuss in the church - see here for

details, including King's comments. Yet protests continued elsewhere - see, for example, these 1882 incidents from St Jude Liverpool, involving J.W.B. Sproule, a future curate of Christ Church Watney Street. See here

for an account of the 1874 Public Worship Regulation Act (instigated by

Archbishop Tait) and the 1906 report of the Royal Commission on

Ecclesiastical Discipline (in which two of our daughter churches, but

not St George-in-the-East itself, feature in the evidence).

As

for St George-in-the-East: although some of King's 'innovations'

continued under his successors, particularly Harry Jones, they fairly

soon became less controversial, and the parish played little part in

the next phase of ritualism controversies, which concerned fresh

matters such as the 'eastward position' for the celebration of holy

communion, the use of vestments, wafer bread, the 'mixed chalice' (the

ceremonial adding of water to the wine), incense and processional

lights and other similar details. By 1871, 5,000 clergy - including

many from the East End were to sign a Remonstrance [right] to the Archbishops and Bishops protesting against the involvement of

the Privy Council in pronouncing on such matters in the case of Hebbert

v. Purchas,

overturning aspects of the judgement of a lower court in Elphinstone v.

Purchas. Copies of this document are pinned into the registers of

several of our and other local churches. In the 1880s, mosaics which would

have undoubtedly fuelled the protests in King's time were installed

without fuss in the church - see here for

details, including King's comments. Yet protests continued elsewhere - see, for example, these 1882 incidents from St Jude Liverpool, involving J.W.B. Sproule, a future curate of Christ Church Watney Street. See here

for an account of the 1874 Public Worship Regulation Act (instigated by

Archbishop Tait) and the 1906 report of the Royal Commission on

Ecclesiastical Discipline (in which two of our daughter churches, but

not St George-in-the-East itself, feature in the evidence).

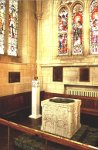

The

only two remaining visual reminders of this extraordinary period are

the metal cladding and iron bar on the inside of the Rectory door, to

protect him from the mob, and the 'Bryan King gate' (re-created in

2007) into what was then the Rectory garden, on the north-west

side of the church, which was his escape route from the church.

The

only two remaining visual reminders of this extraordinary period are

the metal cladding and iron bar on the inside of the Rectory door, to

protect him from the mob, and the 'Bryan King gate' (re-created in

2007) into what was then the Rectory garden, on the north-west

side of the church, which was his escape route from the church.

Bryan King's

eldest son, Bryan M King,

became a convict chaplain in Australia and then vicar of St Peter

Caversham in Dunedin, New Zealand (1882-1911). He took with him his

father's vestments - legend has it that the white chasuble (not

pictured here) still bore

the stains of a rotten egg thrown at him, though it has since been

lovingly cleaned! - and a jewelled chalice bearing the inscription Pray for the officer - a sinner. The Revd

Bryan King, 1860.

This had been given to him anonymously, and was borrowed and returned

to him on Easter Day inset with jewels contributed by friends and

sympathisers [right, and in use on Easter Day 2011].

Bryan King's

eldest son, Bryan M King,

became a convict chaplain in Australia and then vicar of St Peter

Caversham in Dunedin, New Zealand (1882-1911). He took with him his

father's vestments - legend has it that the white chasuble (not

pictured here) still bore

the stains of a rotten egg thrown at him, though it has since been

lovingly cleaned! - and a jewelled chalice bearing the inscription Pray for the officer - a sinner. The Revd

Bryan King, 1860.

This had been given to him anonymously, and was borrowed and returned

to him on Easter Day inset with jewels contributed by friends and

sympathisers [right, and in use on Easter Day 2011].  His grandson Vincent Bryan King

served in the Diocese of Dunedin from 1904 to his death in 1954 and was

involved in social service work (there are various trusts bearing the

family name), as did his his great-grandson Meyrick

Vincent Bryan King, from

1948 to his death in 1988/9. Through them, the vestments and

chalice came into the care of St Paul's Cathedral

where they

are greatly prized: the chalice is used at Easter and other major

festivals, including ordinations. The diocese followed with

interest our programme to

mark the 150th anniversary of the riots, and included an article in the

Easter 2010 edition of the diocesan newsletter Southern See;

Margaret Harding, the cathedral scaristan, was with us for our

anniversary of consecration in July and brought good wishes and

photographs. Right is an article from the Otago Daily Times of 13 April 2013.

His grandson Vincent Bryan King

served in the Diocese of Dunedin from 1904 to his death in 1954 and was

involved in social service work (there are various trusts bearing the

family name), as did his his great-grandson Meyrick

Vincent Bryan King, from

1948 to his death in 1988/9. Through them, the vestments and

chalice came into the care of St Paul's Cathedral

where they

are greatly prized: the chalice is used at Easter and other major

festivals, including ordinations. The diocese followed with

interest our programme to

mark the 150th anniversary of the riots, and included an article in the

Easter 2010 edition of the diocesan newsletter Southern See;

Margaret Harding, the cathedral scaristan, was with us for our

anniversary of consecration in July and brought good wishes and

photographs. Right is an article from the Otago Daily Times of 13 April 2013.

There are two ironies

here (pointed out by Gordon Parry in Cathedral in the Octagon [images right]:

There are two ironies

here (pointed out by Gordon Parry in Cathedral in the Octagon [images right]:  (2) in 1990, Penny Jamieson [left] became

the bishop of Dunedin, serving from 1990-2004 - the second woman bishop

in the Anglican communion, and the first to be a diocesan bishop.

Our parish wholeheartedly applauds this - but what would Bryan King and

his contemporaries have made of it?

(2) in 1990, Penny Jamieson [left] became

the bishop of Dunedin, serving from 1990-2004 - the second woman bishop

in the Anglican communion, and the first to be a diocesan bishop.

Our parish wholeheartedly applauds this - but what would Bryan King and

his contemporaries have made of it?