Charles Booth Life & Labour of the People in London

Third Series: Religious Influences, vol 2 - London north of the Thames - the Inner Ring:

chapter 1, Whitechapel & St George's-in-the-East (Macmillan 1902)

I

have now reached the point at which my study of London began fifteen

years ago, and in this final review am able to note the changes that

have taken place under my own observation, as well as those of earlier

date recorded by some who have devoted themselves to religious,

philanthropic or educational work in this district for twenty, thirty,

forty or even, in one or two instances, for fifty years. [Map of

parishes left; census statistics right]

I

have now reached the point at which my study of London began fifteen

years ago, and in this final review am able to note the changes that

have taken place under my own observation, as well as those of earlier

date recorded by some who have devoted themselves to religious,

philanthropic or educational work in this district for twenty, thirty,

forty or even, in one or two instances, for fifty years. [Map of

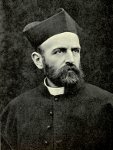

parishes left; census statistics right] Though the parish of St. Augustine, like the others, has been overrun by the Jews, the vicar [Harry Wilson, right] has

succeeded in making his church the centre of very active work. He is an

extreme High Churchman, and the services are of the most advanced kind;

such as Low Churchmen would call 'playing with Rome'. He came to a

stagnant parish, and in fourteen years has

multiplied everything by about fourteen. His success shows what a man

of great energy and uncompromising principles of churchmanship, with a

large staff of workers, and a free use of sensational methods, can

accomplish under circumstances apparently the most adverse. The vicar

would attribute his success to the grace of God and the power of the

doctrines that are taught, while others might say that the people are

bought. Money is indeed freely spent here,

and the art of raising it is well understood, but my own impression is

that the influence wielded by the vicar of St. Augustine's is due

rather to the vigour of his personality than either the doctrines

taught or 'the attractive force of £4000 a year'. In one way or another

not only is the church filled, but a firm hold seems to have been

secured upon some five hundred East-End people drawn from his own and

other parishes, for whom the vicar's ideal is that they should

live, move, and have their being in and about the church, all that is

done for them and by them being in pursuit of the conversion and

sanctification of their souls. Many of the workers come from other

districts.

Though the parish of St. Augustine, like the others, has been overrun by the Jews, the vicar [Harry Wilson, right] has

succeeded in making his church the centre of very active work. He is an

extreme High Churchman, and the services are of the most advanced kind;

such as Low Churchmen would call 'playing with Rome'. He came to a

stagnant parish, and in fourteen years has

multiplied everything by about fourteen. His success shows what a man

of great energy and uncompromising principles of churchmanship, with a

large staff of workers, and a free use of sensational methods, can

accomplish under circumstances apparently the most adverse. The vicar

would attribute his success to the grace of God and the power of the

doctrines that are taught, while others might say that the people are

bought. Money is indeed freely spent here,

and the art of raising it is well understood, but my own impression is

that the influence wielded by the vicar of St. Augustine's is due

rather to the vigour of his personality than either the doctrines

taught or 'the attractive force of £4000 a year'. In one way or another

not only is the church filled, but a firm hold seems to have been

secured upon some five hundred East-End people drawn from his own and

other parishes, for whom the vicar's ideal is that they should

live, move, and have their being in and about the church, all that is

done for them and by them being in pursuit of the conversion and

sanctification of their souls. Many of the workers come from other

districts. | Footnote: Of such of the members of the poorest of these congregations as could be classified by employment we have the subjoined particulars. Doubtless there would be in addition wives and other females engaged in household duties: — 5 engineers, 7 carpenters, 1 blacksmith, 1 plasterer, 1 mason, 3 bakers, 2 sailmakers, 1 ropemaker, 1 tarpaulin maker, 1 diver, 4 sailors, I bookbinder, 1 hatter, 1 gunmaker, 3 policemen, 2 postmen, 1 dairyman, 10 shopkeepers and shop assistants, 18 clerks (all small), 1 rent collector, 2 sanitary inspectors, 14 casual dockers or labourers, 15 dockers (regular work), 13 dray and carmen, 7 warehousemen, I cooper, 2 costers, 14 tailoresses, 12 dressmakers, 1 shirtmaker, 7 laundresses, 3 charwomen, 6 servants, 4 nurses, 6 jam and sweet-makers, 6 teachers; total 175. |

The general system adopted, which I shall have occasion to describe more fully when I come to the central districts, gives a great deal of life to religion; each chapel has its orchestra, and each pulpit is a centre of social and political as well as religious propaganda. The work of the mission undoubtedly does bring religious-minded people together, the motive as usual being for the most part the evangelization of others. This object is attempted by just the same methods as are employed elsewhere and with no materially different results. The most powerful religious influence exerted takes the shape of a reaction on the lives of the workers themselves. The money needed is collected mainly from their own co-religionists, and the usual sensational appeals are issued.

| footnote: The following extract from the Christian World (January, 1901) gives the most recent statistics : — MEDLAND HALL TENTH BIRTHDAY CELEBRATION The 'Home of the Homeless' and Medland Hall, Ratcliff, E., was first opened as a free shelter for destitute men on January 5th, 1891, and on Sunday a special birthday service was held to commemorate the ten years' work. In one decade the 'shelter' has taken a unique place among the philanthropic efforts on behalf of the outcasts of London. For the first four years the admissions of men for shelter at the hall averaged 170,000 a year. Then they had no bunks to sleep in; last year 148,820 men were admitted and provided with separate beds and comfortable bedding. In all, during ten years nearly a million and a half of men have benefited by the hall, and over 300 tons of bread have been supplied. The figures for 1900 have just been compiled by Mr. E. Wilson Gates, the director of the Philanthropic Branch of the London Congregational Union. They are eloquent statistics, and go far to prove that Medland Hall is indeed a home for lost and starving men. ... The number of men helped was 12,896, giving each man an average of twelve nights in the hall. As a matter of fact 6155 used the hall for from two to six nights, while 836 were only once sheltered and fed; 8576 were turned away for lack of room; 104 men were provided for during their first week of employment, 23 were gratuitously supplied with surgical appliances, and 733 with articles of clothing. The largest proportion of the beneficiaries are men between the ages of 30 to 34 and 40 to 44, though 33 men of 70 and over sought refuge in the shelter. All trades and professions were represented, and every county in England had its representation in the year's admissions. Ireland contributed 854, Scotland 635, and Wales 266; 245 men from 24 colonies and dependencies, and 773 foreigners from 26 countries were 'entertained'. The total expenditure was £940, or less than 1½d per man per night. |

Back to History | Back to Charity Organisation Society