St

Matthew Pell Street (Princes Square) 1848-1891 see also parish registers

New

Mulberry Garden Chapel was built for the Countess of Huntingdon's

Connexion in 1805 - its story is told here. The

Connexion

left the area in the 1840s, and the building stood empty for a

time. The Times of 1 March 1847 reported that Messrs Bromley and Son [of 17 Commercial Road] will sell by auction, at

Garraways, on Wednesday, March 17, at 12, by order of the Trustees for

the Sunday Schools and Almshouses belonging to the late Mulberry Garden

Chapel, without any reserve, a valuable LEASEHOLD PROPERTY, comprising a

spacious and lofty brick building of two floors, with extensive vaults

under, and six tenements adjoining, situate on the West side of

Prince's Square, St George's East. Although

it was very close to the parish church, it was bought by the

London Diocesan

Church Building Society for £1,300 and initially opened as a

mission

chapel. Bryan King, the Rector, raised some concerns over creating a

new district (as well he might - the church, though active, did not

survive long), but gave his consent. Ewan Christian, architect to the

Ecclesiastical Commissioners,

surveyed the building and insisted that it must be repaired and

refurnished

before it was fit for purpose. This was done, at a cost of

£400 (provided by Mr Coope of Brentwood),

and it was consecrated on 4 November 1859, with 650 sittings, and

assigned a district by Order in Council on 7 March 1860, with the

Bishop of

London as patron (replacing the previous patrons). The

Commissioners made a grant of £100 towards the

minister’s

stipend, which the Home Mission Fund matched, but the endowment was

only £40 a year, and there was no house - the first minister lived at

17

Princes Square, near where St Matthew's National Schools were later

built. His income was made up by a chaplaincy to one of the City

warehouses and by private subscriptions.

New

Mulberry Garden Chapel was built for the Countess of Huntingdon's

Connexion in 1805 - its story is told here. The

Connexion

left the area in the 1840s, and the building stood empty for a

time. The Times of 1 March 1847 reported that Messrs Bromley and Son [of 17 Commercial Road] will sell by auction, at

Garraways, on Wednesday, March 17, at 12, by order of the Trustees for

the Sunday Schools and Almshouses belonging to the late Mulberry Garden

Chapel, without any reserve, a valuable LEASEHOLD PROPERTY, comprising a

spacious and lofty brick building of two floors, with extensive vaults

under, and six tenements adjoining, situate on the West side of

Prince's Square, St George's East. Although

it was very close to the parish church, it was bought by the

London Diocesan

Church Building Society for £1,300 and initially opened as a

mission

chapel. Bryan King, the Rector, raised some concerns over creating a

new district (as well he might - the church, though active, did not

survive long), but gave his consent. Ewan Christian, architect to the

Ecclesiastical Commissioners,

surveyed the building and insisted that it must be repaired and

refurnished

before it was fit for purpose. This was done, at a cost of

£400 (provided by Mr Coope of Brentwood),

and it was consecrated on 4 November 1859, with 650 sittings, and

assigned a district by Order in Council on 7 March 1860, with the

Bishop of

London as patron (replacing the previous patrons). The

Commissioners made a grant of £100 towards the

minister’s

stipend, which the Home Mission Fund matched, but the endowment was

only £40 a year, and there was no house - the first minister lived at

17

Princes Square, near where St Matthew's National Schools were later

built. His income was made up by a chaplaincy to one of the City

warehouses and by private subscriptions.

| An 1863 Guide to the Church Services in London and its suburbs lists Sunday services at 11am (HC on the first Sunday of the month) and 6.30pm, with a weekday service on Wednesday at 7pm. The

'Churches' section of Charles Dickens Jnr's 1879 Dictionary

of London lists the Sunday services as 11am Matins, Litany &

Ante-Communion

and 6.30pm Evensong, with Evensong on weekdays at 7pm and

Matins on

holy days at 11am. It does not say when the Holy Communion was

celebrated. They used 'Anglican music', and the hymnbook was Ancient & Modern Revised.

(This was presumably the second edition of 1875 by William Henry Monk

of the 1861 original plus the 1868 appendix.) [This pattern - 11am and 6.30pm on Sundays, and Wednesday at 7pm - continued until the church closed.] |

The organ, of 1866, was by A.W. Coleman, a local builder who was

organist at St John Wapping (where he rebuilt the instrument, and gave

the opening recital, the following year); he also built a large

instrument (3 manuals, 34 speaking stops) at St John Bethnal Green, and

began the rebuild at St Philip Stepney in 1872, but then ceased

business - and perhaps died. He was for some time in partnership with

Thomas Richard Willis, who had opened his Tower Organ Works at 29

Minories in 1827 - it burnt down in 1890. See further 'Notes and

Queries' in the British Institute of Organ Studies Reporter vol 5.1 (1981).

The organ, of 1866, was by A.W. Coleman, a local builder who was

organist at St John Wapping (where he rebuilt the instrument, and gave

the opening recital, the following year); he also built a large

instrument (3 manuals, 34 speaking stops) at St John Bethnal Green, and

began the rebuild at St Philip Stepney in 1872, but then ceased

business - and perhaps died. He was for some time in partnership with

Thomas Richard Willis, who had opened his Tower Organ Works at 29

Minories in 1827 - it burnt down in 1890. See further 'Notes and

Queries' in the British Institute of Organ Studies Reporter vol 5.1 (1981). CLERGY

Clergy prior to the creation of St Matthew's as a district churchJ.S.

Hanna (1840s) - though his name does not appear in any registers.

Algernon

Sydney Thelwall (1848-50

and 1852-53, alternating with two periods as full-time secretary of the

Trinitarian

Bible Society

which he had founded in 1831). Born at Cowes on the Isle of Wight in

1795, he graduated from Trinity College Cambridge in 1818 (18th Wrangler - a mathematical classification, though see here for some student translations of the Odes of Horace). He was ordained the following year, and spent seven years at the

English church in Amsterdam as a missionary to

the Jews (later, in 1847, publishing Old Testament Gospel: or Tracts for the Jews). He returned to become curate of Blackford in Somerset.

He was a prolific writer of tracts and polemical works,

defending the Church of England's position against Roman Catholics

(including opposing the Maynooth grant) and Irvingites (eg A Scriptural Refutation of Mr Irving's Heresy 1834). In 1839 he produced The

iniquities of the opium trade with China: being a development of

the main causes which exclude the merchants of Great Britain from the

advantages of an unrestricted commercial intercourse with that vast

empire; with extracts from authentic documents, drawn up at the request

of several gentlemen connected with

the East-India trade. Examples of other writing include Thoughts in Affliction (1832); Letters to a Friend whose mind had been

long harassed by many objections against the Church of England (1835); The Heidelberg Catechism (1850).

In 1843, when he

was (briefly) minister of Bedford Chapel in Bloomsbury, he arranged a

lecture series which the Protestant

Magazine advertised thus:

| Protestant Truth

As Maintained In The Church Of England.—We rejoice to find that

the

Rev. A. S. Thelwall, whose name is endeared to every lover of the

truth for which our martyrs bled, through his unwearying zeal in the

sacred cause, has arranged a series of lectures, to be delivered on

the momentous points of our common faith, now assailed by false

brethren on every side. The following is the prospectus of this

excellent plan—we trust many will avail themselves of it:— [details follow of the 14 lectures, 4 of which

Thelwall delivered himself]

While 'certain parties' do not scruple to avow their their object is 'the un-protestantizing of the National Church', does it not behove all those who really love the Church of England, to stand forward in its defence, and to maintain its Protestant principles, with a boldness and zeal proportioned to the energy and subtlety with which those principles are assailed or undermined? Under the conviction that the present circumstances of the church require peculiar and vigorous exertions on the part of all its faithful ministers, it is proposed that a series of lectures should be delivered at Bedford Chapel, Charlotte Street, Bloomsbury, on Protestant Truth As Maintained By The Church Of England, by clergymen who are zealously and affectionately attached to the principles of that church, as set forth in its articles, homilies, and liturgy. To commence, 'if the Lord will', on Wednesday Evening, April 12th; and to be continued regularly every Wednesday evening till the course is concluded. Divine service to commence at seven o'clock precisely. The countenance and encouragement of all true Protestants, and especially of all faithful clergymen, is earnestly solicited; and, above all things, their earnest prayers that this effort to uphold the truth of the gospel may be accompanied with the blessing of the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, and be made subservient to the true welfare of the church in these lands. It is proposed that the sermons should be printed in a volume, as soon as possible after the course is finished. |

From

1850 until his death in 1863 Thelwall was the Lecturer on

Public

Reading at King’s College London. His introductory lecture

was entitled The

importance of Elocution in connexion

with Ministerial Usefulness. Breathing

through the nostrils to avoid fatigue to the vocal organs was the

secret, he claimed. In this, he continued the work of his father John

Thelwall (1764-1834), poet and orator, friend of Wordsworth and Coleridge, who was a pioneer teacher of the new science

of elocution (and who cured his lisp with false teeth - see here for a 'song without sibilants' which he wrote, perhaps to help those similarly afflicted). John Thelwall's

'logopædic' technique was published as Treatment of

Cases of Defective Utterance (see Denyse Rockey 'John Thelwall and the Origins of British Speech Therapy' in Medical History 23 (1979), pages 156–175). However, John Thelwall

was more widely known known as a political

radical (naming his sons Algernon Sydney and John

Hampden after 17th century republicans); he was unsuccessfully

prosecuted in 1794 on a charge of high treason.

In 1828 A.S. Thelwall married Georgiana Tahourdin,

from a Huguenot family, one of whom had been a curate at St

George-in-the-East 60 years earlier; one of their sons, Sydney, was

also a clergyman and scholar - a translator of Tertullian; incumbent of Radford Semele, he died in 1922.

David

Brown Moore was

curate at St George's from 1851, Lecturer from

1854-59 (and perpetual curate of St Matthew's), and continued as

chaplain of the workhouse into the next decade. Born in Rotherhithe in 1799, he was ordained in 1836 and had

been a workhouse chaplain in Birmingham, and from 1846 the first

incumbent of

the new parish of St Andrew, Watery Street (or Garrison

Lane), Bordesley, carved out of Aston parish in 1846 with a

sandstone church in pointed Gothic style (costing £3,500) - a

'Commissioners'' or 'Million Act' church erected under Sir Robert

Peel's 1818 Church Building Act,

and the fifth church of the Birmingham Church Building Society, prior

to the creation of Birmingham diocese in the diocese of Worcester. His

stipend there was £150 plus pew rents. A school was

established for 120 boys, 120 girls and infants, with an evening

school on four evenings for those who worked during the day. He married

Birmingham-born Hannah Cox, 28 years his junior, at St Dunstan in the

West in 1849.

In London, he took on the remainder of a seven-year lease

of 18 St Ann's Terrace, Hackney from the Revd Josiah Viney, a

Congregational minister (and author of The Prison Opened & The Captive Loosed: Or, The Life of a Thief as seen in the Death of a Penitent (1854)) before the bishop moved him to 15 St George's Place. At the Old Bailey in December 1851 (scroll to case

123)

five men and a woman were convicted - and four of them imprisoned - of

cheating and defrauding him, as leaseholder of the house in Hackney,

and

several others, and also of acquiring a phaeton, harnesses and other

items, by providing false references and then bolting, though by then

the house was in the hands of an agent and Moore did not give evidence.

He later lived at 78 Virginia Terrace [now

Street], just off The Highway. He served as chaplain to

the Essex and Colchester Hospital from 1859, and in the 1861 census

(when he was 62) is shown as curate of Holy Trinity Hoxton, living at

76 Herbert Street, Shoreditch with his wife, 2-year old daughter

Beatrice Mary and a servant. He died in London in 1882, and Hannah in

1898: she was buried at Grangetown Cemetery, Sunderland.

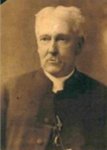

The

first Vicar (and also Lecturer at the parish church, officiating

at a few baptisms and weddings in Bryan King's absence), from

1859-70, was Thomas Richardson.

He was born in Lancaster, and as a young clerk in the City became

involved with Christ Church Chelsea, whose vicar was an early total

abstainer and keen distributor of tracts. Richardson trained at St Bees in Cumbria, since

his uncle, the Mayor of Leeds, who financed him, disapproved of the

'Puseyite' universities. He served three curacies, in south London and

the City, and preached regularly at the Royal Exchange. He was among

the clergy mentioned

by Lord Shaftesbury in his speech in a House of Lords debate of 1860, opposing the motion of Lord Dungannon

to call attention to the performance of Divine Service at Sadler's

Wells and other Theatres by Clergymen of the Church of England on

Sunday Evenings; and to move a Resolution, that such Services, being

highly irregular and inconsistent with Order, are calculated to injure

rather than advance the Progress of sound religious Principles in the

Metropolis and throughout the Country.

The

first Vicar (and also Lecturer at the parish church, officiating

at a few baptisms and weddings in Bryan King's absence), from

1859-70, was Thomas Richardson.

He was born in Lancaster, and as a young clerk in the City became

involved with Christ Church Chelsea, whose vicar was an early total

abstainer and keen distributor of tracts. Richardson trained at St Bees in Cumbria, since

his uncle, the Mayor of Leeds, who financed him, disapproved of the

'Puseyite' universities. He served three curacies, in south London and

the City, and preached regularly at the Royal Exchange. He was among

the clergy mentioned

by Lord Shaftesbury in his speech in a House of Lords debate of 1860, opposing the motion of Lord Dungannon

to call attention to the performance of Divine Service at Sadler's

Wells and other Theatres by Clergymen of the Church of England on

Sunday Evenings; and to move a Resolution, that such Services, being

highly irregular and inconsistent with Order, are calculated to injure

rather than advance the Progress of sound religious Principles in the

Metropolis and throughout the Country.

|

The incumbent of St Matthew’s, St

George’s-in-the-East, a

young minister, who has been very zealous in going about the poorer

classes, and has acquired much experience of their character, states: I have preached at the Obelisk in Southwark, in Ratcliff

Highway; I have preached for two seasons on the steps of the Royal

Exchange; and last Sunday I preached at the Garrick Theatre. The place

was densely crowded by persons of a class I never before got

at.

Mark these words, my Lords, never before got at,

from a

person so conversant with these classes. I have carefully

inquired' he adds, from the city missionaries,

and I find

that their meetings are better attended, a deeper religious feeling

pervades them, and their access to the homes of the people is much more

easy. |

Later in his speech Lord Shaftesbury quotes Richardson as saying My congregations have increased ever since I preached at the Garrick, and the increase has been from the lowest orders. Similar comments are quoted from R.H. Baynes of St Paul's - These

services have in no way affected my evening congregation, though my

church is nor more than three or four hundred yards from the theatre; from Charles Stovel - If anything, the evening attendance has improved; and from Hugh Allen, by then Rector of St George Southwark - None

of my church services have been at all diminished, either in number or

interest; and I have no hesitation in saying that these special

services at the theatres, so far as they have come under my notice,

were attended principally by the class of persons for whom they were

instituted, and the attention given to my preaching there was as solemn

and as marked as ever I witnessed in any church.

The

Church Pastoral Aid Society

provided curates, financed to the tune of £100 annually by

William Wainwright, owner of a local sugar refinery.

Many German sugar workers came to St Matthew's for weddings, because

the fees at the German

Church

were

high, and Richardson learnt German in order to conduct the

services. This pattern continued in his successor's time - see here for more details. He

established a branch of the

Band of Hope (a temperance

organisation for working class children, founded in 1847 and continuing

as Hope

UK helping children to make drug-free choices). He continued to

preach around the country for the Home

Mission Union, and throughout his life remained a keen distributor of

tracts, both through

organised congregational visiting and in the streets. (On one occasion

he walked from Bournemouth to London distributing them.) From

1870 to his death in 1901 he was the first vicar of St Benet Stepney;

there he wrote a series

of tracts under the title Faithful

Boughs,

and

in 1876 founded a

Bible and Prayer Union which claimed 30,000 members worldwide by the

end of the century. I was awakened, he

said, but did not find Christ

till I read my Bible personally. Richardson’s

wife Anna (whom he married during his time at St

Matthew's) wrote a memoir of her husband under

the title Forty

Years' Ministry in East London (Hodder

& Stoughton 1903). Here

are some extracts from his notebooks from his time at St Matthew's,

plus a paper read at a meeting of the Rural Deanery of Limehouse in

1864, advocating parochial temperance societies (he was secretary of

the Church of England and Ireland Temperance Reformation Society, and

listed among the 500 Anglican clergy who were 'total abstainers'), and

his address to the 1870 Church Congress - note his comments on poverty relief and emigration.

The

Church Pastoral Aid Society

provided curates, financed to the tune of £100 annually by

William Wainwright, owner of a local sugar refinery.

Many German sugar workers came to St Matthew's for weddings, because

the fees at the German

Church

were

high, and Richardson learnt German in order to conduct the

services. This pattern continued in his successor's time - see here for more details. He

established a branch of the

Band of Hope (a temperance

organisation for working class children, founded in 1847 and continuing

as Hope

UK helping children to make drug-free choices). He continued to

preach around the country for the Home

Mission Union, and throughout his life remained a keen distributor of

tracts, both through

organised congregational visiting and in the streets. (On one occasion

he walked from Bournemouth to London distributing them.) From

1870 to his death in 1901 he was the first vicar of St Benet Stepney;

there he wrote a series

of tracts under the title Faithful

Boughs,

and

in 1876 founded a

Bible and Prayer Union which claimed 30,000 members worldwide by the

end of the century. I was awakened, he

said, but did not find Christ

till I read my Bible personally. Richardson’s

wife Anna (whom he married during his time at St

Matthew's) wrote a memoir of her husband under

the title Forty

Years' Ministry in East London (Hodder

& Stoughton 1903). Here

are some extracts from his notebooks from his time at St Matthew's,

plus a paper read at a meeting of the Rural Deanery of Limehouse in

1864, advocating parochial temperance societies (he was secretary of

the Church of England and Ireland Temperance Reformation Society, and

listed among the 500 Anglican clergy who were 'total abstainers'), and

his address to the 1870 Church Congress - note his comments on poverty relief and emigration.

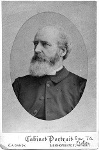

John

Mortier Fidler

[left] was the next Vicar

(1870-89). He was born in Grenada in 1831, where for 32 years his father William

(1796-1866) was a

Methodist missionary, described by a contemporary as a faithful minister of the gospel, a strict disciplinarian, and a diligent pastor. His diary for 1825-27 records his first journey to St Vincent. Four of his seven children became or married Methodist ministers, and according to his great-great-great-grandson Kevin Laurence

(born in Trinidad to a West Indian father and English mother) the

Methodist ethos remained strong through four generations: cousins

intermarried rather than marrying 'out'; they were teetotal; committed

to education (two grand-daughters founded a school in Sydney,

Austrialia, and a grandson was headmaster of a boys' school in

Grahamstown, South Africa); and not without eccentricity - for

instance, when William's grand-daughter Jessie went to the cinema she

bought two entire rows of tickets to ensure that no-one blocked her

view). John, however, became an Anglican! He worked as a chemist in the Midlands from 1846

to 1863 before training at King’s College London, serving curacies at

St John Battersea - then in Winchester diocese - and came to St Matthew's after a spell

with the London Diocesan Home Mission, Spitalfields. His wife

Mary Ann (née Garton) - they married in Bridlington in 1855 -

died

in 1865, aged 39; they had no children. At first he lodged with the

Roberts family

at 62 Philpot Street (near the London Hospital),

and later moved to Prince's Square. He died of nephritis, aged

58, and was buried by his curate Charles Brooke.

John

Mortier Fidler

[left] was the next Vicar

(1870-89). He was born in Grenada in 1831, where for 32 years his father William

(1796-1866) was a

Methodist missionary, described by a contemporary as a faithful minister of the gospel, a strict disciplinarian, and a diligent pastor. His diary for 1825-27 records his first journey to St Vincent. Four of his seven children became or married Methodist ministers, and according to his great-great-great-grandson Kevin Laurence

(born in Trinidad to a West Indian father and English mother) the

Methodist ethos remained strong through four generations: cousins

intermarried rather than marrying 'out'; they were teetotal; committed

to education (two grand-daughters founded a school in Sydney,

Austrialia, and a grandson was headmaster of a boys' school in

Grahamstown, South Africa); and not without eccentricity - for

instance, when William's grand-daughter Jessie went to the cinema she

bought two entire rows of tickets to ensure that no-one blocked her

view). John, however, became an Anglican! He worked as a chemist in the Midlands from 1846

to 1863 before training at King’s College London, serving curacies at

St John Battersea - then in Winchester diocese - and came to St Matthew's after a spell

with the London Diocesan Home Mission, Spitalfields. His wife

Mary Ann (née Garton) - they married in Bridlington in 1855 -

died

in 1865, aged 39; they had no children. At first he lodged with the

Roberts family

at 62 Philpot Street (near the London Hospital),

and later moved to Prince's Square. He died of nephritis, aged

58, and was buried by his curate Charles Brooke.

| At St Matthew's Princes-square, East, on Tuesday evening last the first

meeting of the winter session was held in the Girls' School. The room was

crowded, notwithstanding the admission was by payment. An entertainment

was provided by Mr. W. Rains, assisted by the Misses Rawlings and Thompson,

Masters Oliver and Jennings, Messrs. Gaved, T. Coates, Mason, and Woonton. Mr.

E.A. Price presided at the pianoforte. Recitations were given by Messrs.

Piper and Rains, and the latter gave a short address. Several pledges

were taken at the close. |

Charles

Davies - who may have served for a time in this parish, and whose story

is told here

- included this description, in his 1873 book Orthodox

London, of the Midnight Meeting

for street workers held at St Matthew's Schoolroom, one of the various

local

attempts to address these issues. His journalistic style is the clue to

the popularity of his works.

Curates

Charles

Lacy Kingsmill (1864-67)

was an Irishman, born in Kilkenny in 1830 (later drawing some income

from a family estate there), and a graduate of King's College

Cambridge. Ordained to serve at St Matthew's, after three further

London curacies he went, with a wife

and five young

children, to be chaplain of the British Church at Batavia in the Dutch

East

Indies [left], also teaching

at the gymnasium in Salemba; but he did not feel

sufficiently stretched there - complaining of compulsory idleness - so moved to New South Wales in 1879 where he was

rector of a succession of five parishes and became a Canon of St

Saviour’s Cathedral, Golbourn. He was a popular preacher on a range of public issues, with a keen interest in European

military history: the

history of European warfare he knew as his alphabet, and while he was

essentially a man of peace his voice and pen often warned Australia

against the perils of the future. In a sermon in 1899 at the start of the Boer

War he said war often saves more war,

and

there are worse things than war, and he challenged the Boers' biblical claim of racial supremacy: if you choose to piece together bits of the Bible ... you can prove anything you like. He died in 1910 at Manly,

having

broken

his leg trying to stop a bolting horse. See Peter Edwards Arthur Tange: Last of the

Mandarins (Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2006, pages 7-8).

Charles

Lacy Kingsmill (1864-67)

was an Irishman, born in Kilkenny in 1830 (later drawing some income

from a family estate there), and a graduate of King's College

Cambridge. Ordained to serve at St Matthew's, after three further

London curacies he went, with a wife

and five young

children, to be chaplain of the British Church at Batavia in the Dutch

East

Indies [left], also teaching

at the gymnasium in Salemba; but he did not feel

sufficiently stretched there - complaining of compulsory idleness - so moved to New South Wales in 1879 where he was

rector of a succession of five parishes and became a Canon of St

Saviour’s Cathedral, Golbourn. He was a popular preacher on a range of public issues, with a keen interest in European

military history: the

history of European warfare he knew as his alphabet, and while he was

essentially a man of peace his voice and pen often warned Australia

against the perils of the future. In a sermon in 1899 at the start of the Boer

War he said war often saves more war,

and

there are worse things than war, and he challenged the Boers' biblical claim of racial supremacy: if you choose to piece together bits of the Bible ... you can prove anything you like. He died in 1910 at Manly,

having

broken

his leg trying to stop a bolting horse. See Peter Edwards Arthur Tange: Last of the

Mandarins (Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2006, pages 7-8).

Richard Hitchman (1869),

like the vicar Thomas Richardson, was listed by the Church of England

and Ireland Temperance Reformation Society as a 'total abstainer'. His time here was brief. He had trained at St Aidan's College

Birkenhead, served curacies at St Peter's Derby (where he lectured on The History of the United Church of England and Ireland), Willington in Staffordshire (publishing a well-reviewed lecture on The Bible and Teetotalism), and Kent, before coming to

London. He joined the Victoria Institute,

or Philosophical Society of Great Britain (founded in 1865 as a

response to Darwinism: it was not formally opposed to evolutionary

theory, but shared the views of the 'broad church' Essays and Reviews, published to defend the great truths revealed in Holy Scripture ... against the opposition of Science falsely so called). Hitchman produced several other books and pamphlets, including Miracles (pamphlet of 1866), The Protestantism of the Church of England, Essays on the Christian Church and The Christian Priesthood (1867), and Rise & Progress of the Papal Power (1869, condensed from the Ecclesiastical History of Johann Mosheim (1694-1755)). In his next post, as curate of the new district church of St Paul Clerkenwell, he became committed to the

cause of Canadian emigration, through the East End

Emigration and

Relief Society: see here

for details of the proposed 'New Clerkenwell' settlement there.

Although aspects of the scheme were altered, it was broadly successful,

and the Clerkenwell Emigration Society was renamed the 'Royal Canadian

Emigration Club', with the motto 'piety, sobriety, industry'.

Frederick Haslock (or Hasluck) (1872-75) was born in Arnee, Madras in the East Indies; he married Hannah Ladbury in Stourbridge in 1863 (they had four children) and was ordained in 1872 to serve at St Matthew's. The following year he proposed the creation of a Total Abstinence Society at his masonic lodge, St John's (of which he was chaplain). After a stint at St Luke, Millwall he became curate-in-charge of the new Grove mission district at All Saints, Grays Thurrock - with an iron church, a mission hall and an institute - until his death in 1906 in Southend, survived by his second wife Louisa. (A permanent church, designed by Sir Charles Nicholson, was consecrated in 1927.) He appealed regularly for funds; in 1892, in the London Standard

| HOLIDAY for the POOR—Who will send a DONATION towards giving one hundred women belonging to Mothers' Meeting, and Two Hundred and Fifty Sunday School Children, all of the poorest class, a Day at the Seaside, to the Rev. F. Haslock, Grays, Essex (London over the Border) |

and in 1895 he endorsed To-Day - It

is one of the best, healthiest and outspoken of our weeklies. In my

work as a clergyman among 7,000 of the poorest of dock labourers and

others, I have been much helped by its various articles, and many of

the ideas which it so ably suggests for the improvement of our people,

I try to put into practice - and he advertised regularly in it [right].

and in 1895 he endorsed To-Day - It

is one of the best, healthiest and outspoken of our weeklies. In my

work as a clergyman among 7,000 of the poorest of dock labourers and

others, I have been much helped by its various articles, and many of

the ideas which it so ably suggests for the improvement of our people,

I try to put into practice - and he advertised regularly in it [right].

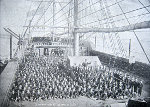

He

was

involved with poor law schools, and was chaplain of the ship Exmouth,

built in 1840 and taken over by the Metropolitan Asylums Board

in 1876, moored off Grays and providing training for poor boys for the

regular and merchant navies [right in 1893]. In 1881

fourteen of the boys (aged 12-15) were from St George-in-the-East

district. It was replaced by a newer vessel in 1905 [far right in 1917] which served until 1939.

He

was

involved with poor law schools, and was chaplain of the ship Exmouth,

built in 1840 and taken over by the Metropolitan Asylums Board

in 1876, moored off Grays and providing training for poor boys for the

regular and merchant navies [right in 1893]. In 1881

fourteen of the boys (aged 12-15) were from St George-in-the-East

district. It was replaced by a newer vessel in 1905 [far right in 1917] which served until 1939.

He also gave weekly religious instruction on the training ship Shaftesbury, established in 1878 by the London School Board

for 350 boys of whom 70 might be Roman Catholics (increased to 500 /

100 in 1881), occasioning this letter to Henry Gover of the LSB and

printed in the church weekly Guardian in 1893:

| It is with considerable reluctance that I am induced to write to you in reference to the various newspaper reports of what you said at the meeting of the London School Board of May 4 on the subject of 'Rules and Regulations for the Shaftesbury'. In the Guardian, of May 10, and several other papers, you are reported as having said: The Church clergyman would not seem to care so much for the welfare of the people as did the Roman Catholic priest, for the Catholic priest was ready to give religious instruction freely, while the Church clergyman treated the matter in a mercenary spirit. Mr. Sinclair, who preceded you, is reported to have said he thought it contemptibly mean that any clergyman should want remuneration for giving religious instruction to children. Now I feel quite sure neither of you gentlemen would have made a statement in such strong terms had you been acquainted with the following facts:—For more thani two years last past I have personally and regularly visited the training-ship Shaftesbury once a week (Wednesday mornings) to give religious instruction to the Protestant boys, and this instruction is purely religious, not dogmatic nor doctrinal. Once in each year, so soon as I receive notice from the Bishop of the diocese that he purposes a confirmation either in my own or a near church, with the sanction of the captain and head schoolmaster, I mention the subject to the boys on board, explain carefully the nature and object of confirmation, then I tell the boys if any of them wish to he conflrmed, they may give in their names to the head master; no pressure whatever is put upon them. When I receive the list I arrange to meet these boys alone, weekly, for about six weeks, in order to give them the special instructions required. On a convenient day after they are confirmed they all attend All Saints' Church to make their first Communion; and if you will kindly give me the pleasure of meeting you at your City office, I will show to you the books, memorial cards, &c., which I give to each boy at my own cost. In two years not less than 106 boys have been thus prepared by me and presented to the Bishop, and have won from him the highest commendation for their reverence and good behaviour. I have done this without any hope or thought of payment, only from pure love of the boys, and I have certainly never asked to be paid for it. But, curiously enough, the first and only intimation I had of the question of payment being raised was from the Roman priest whom I meet weekly. My only reply then was, If the Board offer it I shall accept it, but will never ask for it, and to this I still adhere and am still doing the work. I have not written this with any desire or wish for publicity, but solely that you should know that there is a clergyman not quite so mercenary as some would imagine |

Gover withdrew his charge against Haslock, but maintained that his criticism of the Church of England, in view of the facts then before the Board, had been just.

Alfred

Enoch Wicks (1876-77),

born 1846 in Cumbria and trained at St Bees; St Matthew's

was the

fourth of seven curacies, after St Denis York, Hertfordshire and St Thomas

Bethnal Green, going on to Colwich (Staffordshire), Homerton and

Cheswardine (Shropshire), before be became in 1881 vicar of

St Bartholomew Tosside (also known as Tossett, or Haughton), a small

community in

the Forest of Bowland, in the diocese of Ripon. He retired in 1912

(with a £50 pension granted by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners) to

Kneeton Vale, Sherwood, in Nottinghamshire, and died there in 1934 aged 88.

His son Alfred Ernest, who unlike his father studied at Cambridge (St

Catharine's College) and trained for ministry at St Aidan's College

Birkenhead, was Rector of Hollesley in Suffolk from 1929-49.

George Rogers (1881-82)

trained at St Bees and was ordained in Edinburgh in 1878, as a

missionary priest of High School Yard (where John Wesley had preached

over a century before, in 1763, recording in his diary I preached at seven in the High School yard, Edinburgh. It being the

time of the General Assembly, which drew together not the ministers

only, but abundance of the nobility and gentry, many of both sorts were

present; but abundantly more at five in the afternoon. I spake as

plainly as ever I did in my life. But I never knew any in Scotland

offended at plain dealing. In this respect the North Britons are a

pattern to all mankind.) Rogers came here

three years later, and then to St Paul Shadwell from 1882-84. Seven

further, and equally brief,

curacies and other posts followed: Pokesdown in Hampshire; St Thomas

Stamford Hill; St Matthew Bethnal Green; Braxted, in Essex; an

assistant

chaplaincy at St Katharine's,

then based in Regent's Park; St Augustine Kilburn; and St Paul

Knightsbridge - most of these being in the catholic tradition - with no

further recorded posts after 1900.

John Jones (1883-85), formerly a Baptist minister, was ordained

by the Bishop Robertson of

Missouri in 1872 at the behest of the Ecclesiastical Authority of

Illinois; he officiated at many baptisms during his time here.

THE END OF THE LINE

Charles

Stanton Gray was

the final curate (1895-97) and left, explained Turner, because of the reduction of

clerical staff to normal limits. Ironically

in view of the

first vicar's ardent teetotalism, Gray's family were major brewers,

maltsters and corn merchants in Essex. In 1828 his grandfather had

founded a brewery

in Springfield Road, Chelmsford [left] - eventually

sold in 1974 to

cover death duties, and the site redeveloped. His father had acquired

another family brewery in Halstead, where the family lived at The Red

House, but sold it in 1876 to Thomas Francis Adams and retired, with

his wife and five children, to Hastings at the age of 40. There, in

1886, aged 22, Charles Stanton Gray junior set up business briefly as a

photographer, at St Andrew's Studio, 104 Queen's Road and then at 25

White Rock (on the seafront) - carte de visite right.

He then studied at Emmanuel College Cambridge and was ordained in 1888,

serving curacies at Kingston-on-Thames, Acton and St Barnabas

Kensington before coming to St Matthew's; a variety of further curacies

followed at Esher, Gedling, St John's Drury Lane and back in Kingston

before he became incumbent of Hasleton (with Long Melton and

Yanworth) in rural

Gloucestershire - a Lord Chancellor parish with a population of 190. He

retired to Bournemouth and died in 1938, aged 73, leaving a

benefaction

to his college, Emmanuel Cambridge, for those intending to seek

ordination (now used to help fund research students).

Charles

Stanton Gray was

the final curate (1895-97) and left, explained Turner, because of the reduction of

clerical staff to normal limits. Ironically

in view of the

first vicar's ardent teetotalism, Gray's family were major brewers,

maltsters and corn merchants in Essex. In 1828 his grandfather had

founded a brewery

in Springfield Road, Chelmsford [left] - eventually

sold in 1974 to

cover death duties, and the site redeveloped. His father had acquired

another family brewery in Halstead, where the family lived at The Red

House, but sold it in 1876 to Thomas Francis Adams and retired, with

his wife and five children, to Hastings at the age of 40. There, in

1886, aged 22, Charles Stanton Gray junior set up business briefly as a

photographer, at St Andrew's Studio, 104 Queen's Road and then at 25

White Rock (on the seafront) - carte de visite right.

He then studied at Emmanuel College Cambridge and was ordained in 1888,

serving curacies at Kingston-on-Thames, Acton and St Barnabas

Kensington before coming to St Matthew's; a variety of further curacies

followed at Esher, Gedling, St John's Drury Lane and back in Kingston

before he became incumbent of Hasleton (with Long Melton and

Yanworth) in rural

Gloucestershire - a Lord Chancellor parish with a population of 190. He

retired to Bournemouth and died in 1938, aged 73, leaving a

benefaction

to his college, Emmanuel Cambridge, for those intending to seek

ordination (now used to help fund research students).

In 1937 the officials of the boys' club asked the

Ecclesiastical Commissioners if they might buy the building. The

Commissioners were surprised to hear that it was still standing as the

Order for closure specified that it should have been demolished. The

club was ejected, and the building duly pulled down! The site was sold

for £400 which was given, after the War, to the building fund

of

St Mark’s South Ruislip.

Homepage | About Us | Services & Events

| Church &

Churchyard |

History

Newsletters & Sermons | Contacts,

Links & Registers | Giving | Picture

Gallery |

Site Map