Local judges (1) - stipendiary magistrates

Here are some details of those who held office at the Lambeth Street

and Thames Police (Magistrates') Courts, and at Whitechapel County

Court. It demonstrates the shift from 'gentlemen' (those who had been

county JPs before 1792) to a professional caste of barristers. It is

also interesting to compare them with the clergy who held

office locally as incumbents: they too were 'Oxbridge men', some of

them from quite

grand families, some with homes in the country, but did not have the

generous stipends of the judges, and they lived on their patch rather

than

in the West End. Cushioned from the rigours of East End existence,

how much understanding did some of them have of the lives of those who

appeared before them?

The best of them showed a degree of realism - and the worst of them

exploited their position - but almost all were inevitably more aloof

than the

clergy.

The dates in brackets for the years they were attached to particular

courts are somewhat approximate, as lists of the time can be confusing,

and some were attached to more than one London court -

particularly the Shadwell magistrates, who tended also to sit at Queen

Square, Westminster or Hatton Garden (perhaps an indication that this

court, which closed in 1821, was less busy, since the Thames (Marine

Police) court was nearby). Some were also provincial county

magistrates. In the house of was the legal phrase at the time for a sucessor in office following a death, retirement or promotion.

Lambeth Street (1792-1844)

Lambeth Street (1792-1844)

Sir Daniel Williams (1792-1831)

was

the first presiding magistrate at the new court; his nefarious

activities in connection with the licensing laws and other

opportunities for profit are considered here. He was also a Lieutenant Colonel of the 1st Tower Hamlets

Militia and was painted [right] by John Opie (1761-1817) with the Tower in the background. He died in 1831 at his home in Stamford Hill. His namesake son Daniel served on HMS Agamemnon, and was taken prisoner: this letter of Horatio Nelson refers.

Rice Davies (1792-1818) - born 1741; granted a pension of £400 in 1818 (and wanted his arms - presumably hanging in the courtoom!), but died later that year at Neath, Glamorgan. He was replaced by one Munshell [details needed].

Henry

Reynott DD (1792-18??) - see comments here about a Doctor of Divinity's suitability for this post; a relative, Sir James Henry Reynott, was Governor of Jersey

a generation later.

[Another local clerical magistrate of a slightly later period,

appointed as a Middlesex JP in 1821, and sometimes 'assisting' at

Lambeth Street, was the Revd Daniell Mathias

MA (1769-1837), born in Warrington, and a former Fellow of Brasenose

College Oxford who appointed him Rector of St Mary Whitechapel in 1809.

He was energetic in developing schools, for which he published an Explanation of the Church Catechism. His 1837 obituary in the Gentleman's Magazine said he was eminent

for his great skill in separating truth from falsehood, and for his

tact in the examination of witnesses. Mr Mathias made his knowledge of

law subservient to the interests of the religion of which he was the

minister; and from the bench, as well as from the pulpit, he delivered

sentiments calculated to improve base humanity - hardly good

legal practice; and contrast this with a case he heard at Lambeth

Street in 1824, when a rabbi accused Joseph Jones, a donkey driver, of

attempted assault on his daughter Leah Meldola, by forcing her into a

nearby house to eat pork. Mathias summarily dismissed the case as frivolous, reprimanding them for wasting the court's time and describing Jews as a quarrelling people.]

Matthew Wyatt

(1773-1831), barrister of the Inner Temple, was also a magistrate in

Roscommon, Ireland; his sons Thomas Henry and Matthew Digby were noted architects.

William Lorance Rogers FSA (1813-??)

was

the second son of Captain John Rogers, and descendant of Captain John

Rogers who gained distinction by repelling the assault of a Biscay

privateer on a transport ship under his commend in 1704. He was called

to the Bar at the Middle Temple in 1805, but his chambers were

subsequently at 5 Old Square, Lincoln's Inn and his home in Upper

Bedford Place, Russell Square, and later in Hampstead. He was appointed

a magistrate in 1813, sitting at Hatton Garden as well as in the local

courts, and was a member of Fellow of the (Royal) Society of Arts and subscriber to the [science-based] Royal Institution and a bibliophile - bookplate right (motto nos nostraque deo = we and ours to God);

his extensive library was auctioned the year aftert his death in 1838. For a few years, from

1812-15, he was an elected member of 'Nobody's Friends', a dining club

established in 1800 by Richard Stevens (a high churchman and Treasurer

of Queen Anne's Bounty); its influential membership overlapped with the

'Hackney Phalanx' (also known as the 'Clapton sect', as distinct from

the evangelical 'Clapham sect') which had a particular interest in

education reform.

was

the second son of Captain John Rogers, and descendant of Captain John

Rogers who gained distinction by repelling the assault of a Biscay

privateer on a transport ship under his commend in 1704. He was called

to the Bar at the Middle Temple in 1805, but his chambers were

subsequently at 5 Old Square, Lincoln's Inn and his home in Upper

Bedford Place, Russell Square, and later in Hampstead. He was appointed

a magistrate in 1813, sitting at Hatton Garden as well as in the local

courts, and was a member of Fellow of the (Royal) Society of Arts and subscriber to the [science-based] Royal Institution and a bibliophile - bookplate right (motto nos nostraque deo = we and ours to God);

his extensive library was auctioned the year aftert his death in 1838. For a few years, from

1812-15, he was an elected member of 'Nobody's Friends', a dining club

established in 1800 by Richard Stevens (a high churchman and Treasurer

of Queen Anne's Bounty); its influential membership overlapped with the

'Hackney Phalanx' (also known as the 'Clapton sect', as distinct from

the evangelical 'Clapham sect') which had a particular interest in

education reform.

This was the area in which his son William (1819-96) rose to

distinction. (Another son Edward had died in 1829 aged twelve.)

Etonian, student of Balliol, barrister and Durham-trained clergyman,

William 'Hang Theology' Roberts [he was impatient with bickering over

the nature of religious instruction in schools] created a school for

children of the poor at his parish of St Thomas Charterhouse, and

schools for the middle classes when he became Rector of St

Botolph-without-Bishopsgate (and an early promoter of the Bishopsgate

Institute); he was a member of the 1858 Report on Popular Education, a

founding member of the London School Board in 1870 ( but resigned two

years later) and a proponent of free libraries - more details of his

life here,

and in this 1888 memoir by R.H. Hadden, formerly a curate at St

George-in-the-East and one of Rogers' successors at St Botolph's.

John Hardwick FRS (1821-41)

born in 1790, was the son of a well-known architect Thomas Hardwick. He was a Fellow of Balliol College Oxford (BCL and DCL), a barrister of Lincoln's Inn and a capital linguist according to the Illustrated London News of 9 October 1847 which thought this a most advantageous

quality in a 'police judge' presiding over a locality 'swarming with

foreigners' and whose applications for assistance from distressed Poles

and 'other expatriate unfortunates' were so frequent an occurrence.

He was appointed to

Lambeth Street in 1821; was elected Fellow of the Royal Society in

1838; and was a deputy lieutenant for Tower Hamlets. He transferred to

Great

Marlborough Street in 1841 and retired in 1856, living until 1875.

Charles Dickens - who with others such as Cobbett and Black had

campaigned against corruption among the London stipendiaries, causing

the removal of Alan Laing (the model for Mr Fang in Pickwick Papers)

- regarded 'Hardwick of Marlborough Street' as one of the best of the

London magistrates. They became friends, and Hardwick named candidates

for the Urania Cottage

project which Dickens and Angela Burdett-Coutts ran in Shepherd's Bush.

He was involved on various occasions with the prosecution of Ikey

Solomon, said to be Dicken's model for Fagin in Oliver Twist: see John Jacob Tobias Prince of Fences: the life and crimes of Ikey Solomons (1974).

Hardwick's work on 'police subjects' (including his appendix to editions of the late William Dickinson's Practical Exposition of the Law Relative to the Office and Duties of a Justice of the Peace, chiefly out of Session,

first published in 1813 and later running to eight volumes, price £2

14s) influenced the developing organisation of the Metropolitan Police.

Press complaints about the London magistrates continued: in 1846 the London Daily News commented on the discrepancies of punishment, observing that Any rich man may

enjoy the luxury of an assault by paying for it. The fine imposed is

the price of the article. The 'gentleman' buys his knockdown blow, or

wrenched knocker, or smashed lamp, at Bow-street; as he does his coat at Stultz's, or his boots at Host's; but did not apply this specifically to Hardwick. The 1847 article mentioned above said A rather elderly

mild-looking personage, he conducts the business in an

easy and conversational, yet by no means undignified, style and is not

above receiving a hint from any of the minor officials who surround him.

His wife was the

daughter of a colonel in the Swedish artillery. He died in Hove in

1875; The Times obituary noted the inflexible uprightness of his judgements and his extreme urbanity and courtesy of manner.

Thomas Walker

(1829-36)

son of a Manchester cotton merchant (also Thomas) who led the Whig cause

there and founded the Manchester Constitutional Society, and was accused but

acquitted of treason. Thomas junior, born in 1784, went to Trinity College Cambridge,

was called to the bar (Inner Temple) in 1812, and took a special interest in

poor law issues and published Observations on

the Nature, Extent, and Effects of Pauperism, and on the Means of

reducing it (1826 and 1831), and Suggestions for a

Constitutional and Efficient Reform in Parochial Government (1834). Appointed to Lambeth Street in 1829, from 1835 until his death

the following year (unmarried, in Brussels - there was a memorial

plaque in St Mary Whitechapel) he published a weekly journal The Original, intended to raise the national tone in whatever concerns

us socially or individually

but mainly concerned with health and gastronomy: selections on 'The Art

of Dining, and of attaining High Health', and 'Aristology, or the

Art of Dining' were republished in the coming years, with

biographies of father and son.

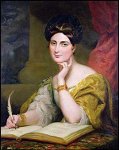

The Hon George Chapple Norton

(1831-54)

born in 1800, grandson of Baron Grantley, who was nicknamed 'Sir Bull-face

Double Fee' because of his success in geting government legal

appointments, and son of the well-paid Baron of the Exchequer in

Scotland, he attended Edinburgh University but does not appear to have

graduated. Through family connections, he became Tory MP for Guildford

1826-30, voting mainly with the party line. He was also appointed Recorder of

Guildford. His Whitechapel magistracy in 1831 (with a salary of £1,000)

debarred him from standing again for Parliament.

This post was fixed by

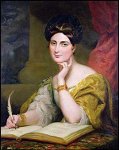

his wife Caroline [right, by George Hayer 1832], daughter of the playwright Sheridan, and herself a considerable

writer - with Lord Melbourne, the Home Secretary. Not only was

she from a family with Whig connections, but also mistress of widower

and philanderer Melbourne [right, by Landseer 1836]. Norton, although he protested undying love

for his childhood sweetheart, was in fact an appallingly violent and

abusive husband; they separated three times, but she returned for the

children's sake. Norton sued Melbourne, who had become Prime

Minister, in attempt to achieve a divorce. Melbourne was acquitted, but

many rash words were spoken by all parties and no-one emerged smelling

of roses [title page of a published version right]. Dickens drew on the case - and the farcical way the lovers'

correspondence was treated in court - for his Pickwick Papers.

Norton then exonerated his wife in an attempt to win her back, and

thereafter denied her a divorce; further washing of dirty linen

followed, and she became a campaigner for women's matrimonial rights in

marriage - leading to the Custody of Infants Act 1839 [far right, by Etty after this Act], the Matrimonial Causes Act 1857 and the Married Women's Property Act

1870. Nevertheless, he continued to hold his magistracy, transferring

to the Lambeth court in 1854, until he retired because of 'failing

health' in

1867, with pension, after 36 years on the bench; he died in 1875.

This post was fixed by

his wife Caroline [right, by George Hayer 1832], daughter of the playwright Sheridan, and herself a considerable

writer - with Lord Melbourne, the Home Secretary. Not only was

she from a family with Whig connections, but also mistress of widower

and philanderer Melbourne [right, by Landseer 1836]. Norton, although he protested undying love

for his childhood sweetheart, was in fact an appallingly violent and

abusive husband; they separated three times, but she returned for the

children's sake. Norton sued Melbourne, who had become Prime

Minister, in attempt to achieve a divorce. Melbourne was acquitted, but

many rash words were spoken by all parties and no-one emerged smelling

of roses [title page of a published version right]. Dickens drew on the case - and the farcical way the lovers'

correspondence was treated in court - for his Pickwick Papers.

Norton then exonerated his wife in an attempt to win her back, and

thereafter denied her a divorce; further washing of dirty linen

followed, and she became a campaigner for women's matrimonial rights in

marriage - leading to the Custody of Infants Act 1839 [far right, by Etty after this Act], the Matrimonial Causes Act 1857 and the Married Women's Property Act

1870. Nevertheless, he continued to hold his magistracy, transferring

to the Lambeth court in 1854, until he retired because of 'failing

health' in

1867, with pension, after 36 years on the bench; he died in 1875.

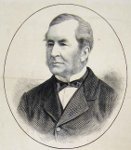

Sir Thomas

Henry (1840-46) - right:

an Irish Roman Catholic, born 1807, graduate of Trinity College Dublin, called to

the Bar at the Middle Temple in 1829, and after working on the northern

circuit was appointed to Lambeth Street in 1840, transferring in 1846

to Bow

Street, where he became chief magistrate. He was a principal architect

of the 1862 Extradition Act, and was a government adviser on licensing (theatres and pubs), betting, and Sunday trading.

Sir Thomas

Henry (1840-46) - right:

an Irish Roman Catholic, born 1807, graduate of Trinity College Dublin, called to

the Bar at the Middle Temple in 1829, and after working on the northern

circuit was appointed to Lambeth Street in 1840, transferring in 1846

to Bow

Street, where he became chief magistrate. He was a principal architect

of the 1862 Extradition Act, and was a government adviser on licensing (theatres and pubs), betting, and Sunday trading.

High Street, Shadwell (1792-1821)

Its original magistrates were George Story (below), John Staples - a relative of John Harriott (1792 until his death in 1800), and

Sir Richard Ford (1792-93)

Born 1758, he was the fourth son of Dr James Ford, physician to King George III and accoucheur

to Queen Charlotte, and joint proprietor with Richard Brindsley

Sheridan of Drury Lane Theatre. After Westminster School, he was called

to the bar at Lincoln's Inn in 1782 and practised for a time on the

Western circuit. He was briefly a Member of Parliament, for East

Grinstead in 1789-90 and (at the opposite end of the country) Appleby

in 1790-91, both arranged by the Duke of Dorset, but resigned, writing

to Pitt

Lord

Thanet, under whose influence I was returned at the general election

for Appleby, having embraced a system of politics different from that

which I have adhered to, it becomes necessary that I should vacate my

seat soon after the holidays ... Although I was awaare of the nature of

Lord Thanet's sentiments before my election, yet I should be wanting in

justice to myself, were I not to add that this resignation would not

have been required had I chosen to have voted in conformity to them. I

regeret that the period of my remaining in Parliament has been so short

as to have afforded me few opportunities of manifesting my attachment

to your service. I am therefore deprived of any claim to your

recollection of me, at time when the effect which the embarrassed

situation of my father's affairs has had on my situation would render

any employment to which I might be thought not wholly unequel a matter

of the utmost consequence to me.

|

Although there were issues on which he disagreed with the government,

he remained on good terms with his patron (who wrote to Pitt I

have been told that you approved of his parliamentary abilities (but if

he did not exert them during the short time he sat, it was owing to the

delicacy of his situation and not to want of zeal in support of your

administration) and he stands also high in the opinion of his

professional contemporaries, and also with Pitt's ally Charles

Long. The real reason, as he hints, was the collapse of his father's

theatrical interests and his need for paid employment. He had fathered

three children by a Drury Lane actress Dorothy Jordan: she left him for

the Duke of Clarence in 1790 (in 1794 he married Marianne, daughter and

heiress of Benjamin Booth of the East India Company). So in 1792 he

became a stipendiary magistrate, at Shadwell until the following year

when he moved to Bow Street on the death of Sampson Wright: because of

the conventions, he couldn't be senior magistrate over those with

longer service, but he became a key figure in using the court, and its

police team, to further the government's programme against radicalism

and seditious activity, and tracking down offenders, in the wake of

events in France.

Although the other police courts had done little to further this

'anti-democtratic' agenda (which some claim was as much a part of the

rationale of their creation as the reform of the inefficiencies of

policing), Bow Street was more actively engaged, and Ford understood

how Bow Street could meet the needs of the times, explaining to the new

Home Secretary that the Act of 1792 had enlarged that part of the police of the metropolis which is under the control of Government.

In 1802 he said that his daily attendance at the Home Office there was

his most important duty over last 8 years, and he played a key role in

unmasking the Despard conspiracy.

He was also virtually in charge of policing - 'the third

under-secretary in all but name', creating an Entry Book separating

routine policing from Home Office affairs, and drafting many of the

circular letters it issued. He co-ordinated work against spies, French

agents and domestic radicals, sometimes sending infiltrators to their

meetings, and from 1800 superintended the Alien Office (created under a

statute of 1793) to track refugees, and drafted the regulations to

control the entry of foreigners during the peace of Amiens

in 1802. For all of this he was paid an additional £500 a year on

top of his £400 stipend; and when the senior magistrate's post became

vacant in 1801 he was appointed (and given the customary knighthood)

even though he was not the most senior. At the time of his death he was

the acting magistrate for the Home Office.

Ann Hone, who has studied all the documentation, argues that he was not

a fanatical counter-revolutionary. In 1795 had had endorsed Jeremy

Bentham's proposals for prison reform (though came to regard

transportation as a better option). Rather, he was regarded as useful.

He was also made Chief Magistrate of Middlesex in 1800; was Captain of

the St Sepulchre's Volunteers from 1798, and Major Commandant from

1803. He died after a brief illness in 1806, at Sloane Street. See

further J.M. Beattie The First English Detectives (2012). His son Richard was a noted travel writer.

John Nares (1792-94)

The son of Sir George Nares, a judge and Member of Parliament, and

nephew of James Nares, church musician and organist to King George III,

he was a Bencher of the Inner Temple. He married Martha Brigstocke, and

they had four children. He moved on to Worship Street after two years,

and then to Bow Street. In his evidence to the Select Committee on the

Police (1816-18) he said atrocious crimes have of late years considerably diminished; he died in 1818.

Rupert

Clarke (c1801-11)

succeeded Patrick Colquhoun at Worship Street in 1797 and came to

Shadwell, based in an office at Store Street. He died in 1811 aged 76,

after fifty years as a JP, and was a deputy Lieutenant for

Middlesex - so he was a representative of the old-style

magistracy.

The

following three magistrates were in office at the time of the Ratcliff Highway murders in 1811. Lloyd Shepherd characterises

them in his novel English Monster, when challenged by Harriott about

their inactivity: Story sliding into a state of personal transcendence and invoking the bible and the End of Days as the explanation for the murders; Markland a dandified Yorkshireman bemoaning the lack of Home Office and other support, and Capper a

little Hertfordshire man, twittering in a high-pitched voice .... his

pinched, pale white face spotted by two dots of red in his cheeks protesting the unblemished reputation of the Shadwell office.

George Story (or Storie) (1792-1821)

He

was the senior magistrate who encouraged the Home Secretary to have

John Williams' body dragged through the street on a cart to his

suicide's burial at a crossroads. He was also a Commissioner of

Bankrupts, with an office at 6 Southampton Buildings. He retired on a

pension in 1821 when the Shadwell office closed, but died the following

year, aged 73.

Edward Markland (1811-21)

born 1748 into an 'old and respectable' Lancashire family, he pursued a

commercial career in Cadiz until 1775 (marrying, the year before he

left, Elizabeth Hardy, the daughter and co-heiress of the British

Counsul there - they had three sons and two daughters). He then settled

in Leeds, where he was a member of the Corporation, Mayor in 1790 and

1807, and Deputy Lieutenant of the West Riding. Coming to London in

1810, he was appointed a magistrate the following year - serving both at High Street Shadwell and Queen Square Westminster,

retiring to Bath in 1827 due to age and ill health, where he died in

1832 aged 84. He was, said an obituary, well-versed

in the criminal law, active and useful; in politics a consistent Tory;

his religious creed was that of the Established Church, to the

communion of which he steadily and piously adhered throughout his life. It adds cryptically, having described him as cheerful and vivacious, with many friends, far

higher praise is due to one who tried - how hardly tried on the school

of adversity? - to maintain an unshaken spirit of fortitude and patient

endurance... With his other commitments, he seems to have been little engaged with the work at Shadwell.

Robert Capper

Born in 1768 in Bushey, Herts, the fifth child of Richard Capper and

Mary Ord, he married Mary Ann Jenkinson in 1810. Although described

above as a Hertfordshire magistrate, he was in the process of settling

in Cheltenham, at Marle Hill House (now demolished), above Pittville

Park, where the millpond was known as 'Capper's Fish Pond'. Appointed

to both the Shadwell and Hatton Garden courts, his main interests therefore lay

elsewhere; he was appointed a Cheltenham magistrate in 1821. A wealthy man, and a Calvinist, in 1816 he built the

Portland (North Place) Chapel in Cheltenham [left] and appointed a

Baptist minister, Thomas Snow, who refused communion to Capper and anyone else

who hadn't been baptized there. In retaliation Capper refused to pay

Snow’s salary (who had to hold services at his own home instead), and

three years later gave the chapel to the Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion.

The building still stands, but has had various commercial uses and is

currently a fitness club. Capper was also involved, with fellow

Cheltenham magistrates Joseph Overbury and the Revd T.B. Newell DD, in

the Holyoake heresy trial (Judge Cluer, of Whitechapel County Court, later corresponded with Holyoake). He died in 1851 at Cheltenham, aged 83, the oldest

member of the bench there.

Born in 1768 in Bushey, Herts, the fifth child of Richard Capper and

Mary Ord, he married Mary Ann Jenkinson in 1810. Although described

above as a Hertfordshire magistrate, he was in the process of settling

in Cheltenham, at Marle Hill House (now demolished), above Pittville

Park, where the millpond was known as 'Capper's Fish Pond'. Appointed

to both the Shadwell and Hatton Garden courts, his main interests therefore lay

elsewhere; he was appointed a Cheltenham magistrate in 1821. A wealthy man, and a Calvinist, in 1816 he built the

Portland (North Place) Chapel in Cheltenham [left] and appointed a

Baptist minister, Thomas Snow, who refused communion to Capper and anyone else

who hadn't been baptized there. In retaliation Capper refused to pay

Snow’s salary (who had to hold services at his own home instead), and

three years later gave the chapel to the Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion.

The building still stands, but has had various commercial uses and is

currently a fitness club. Capper was also involved, with fellow

Cheltenham magistrates Joseph Overbury and the Revd T.B. Newell DD, in

the Holyoake heresy trial (Judge Cluer, of Whitechapel County Court, later corresponded with Holyoake). He died in 1851 at Cheltenham, aged 83, the oldest

member of the bench there.

Henry Gregg

Described as a gentleman, he

had been Under Sheriff of London and Middlesex (paid £1,090 a year,

according to the House of Commons Journal for 1777 - rather more than

others in similar offices); his family came from Ilkeston in Derbyshire.

William Archibald Armstrong White FRS FSA (1816-21)

William Archibald Armstrong White FRS FSA (1816-21)

Born

1776, son of the Revd Dr Stephen White, he was a pupil of Westminster School, and was called to the bar at Lincoln's

Inn in 1801, becoming a police magistrate in 1816, in the house of Henry Gregg at Shadwell until its closure, and also at Queen Street, Westminster until his death, giving evidence to a House of Commons enquiry on drunkenness in 1834. He was an antiquarian - co-editing Hayward Townshend's 1601 House of Commons diary,

and an elected Fellow of the Royal Society (1837) - left is his nomination paper; a Fellow of the

Society of Arts; and member of the Camden Society

(for the publication of texts - not to be confused with the Cambridge

Camden Society for ecclesiastical architecture, or the present-day

society for people with learning difficulties). A coin collector, hee

was an early member of

the Numismatic Society

(established in 1836, meeting monthly

back-to-back with the Society of Antiquaries, with modest charges: a

guinea membership, and a guinea entrance). Sothebys printed a catalogue

of his collection in 1848, and the British Museum holds some

of his collection.

He lived in College Street, Westminster (where he died in 1847) and

Castor House, Peterborough [right],

a 3-storey house rebuilt around 1700 which his father, having inherited

a fortune, bought from the church (it possibly had some episcopal

connections) in 1796. bought from the church Northants (which he

inherited in 1824,

family having bought from church). A

son, the Revd Stephen Prescott White LLD, of St Peter's College Oxford

an equity barrister, draftsman and conveyancer, did much work on the

house, and was Treasurer of the Foundling Hospital (as his

great-grandfather had been) from 1830-41. A bachelor, he adopted the

six children of his deceased brother Charles. The house subsequently

passed out of the family.

Thames Police Office / Court (1796-)

The magistrates of

the Thames Police Office at 259 Wapping High Street were initially

designated 'special justices' because of their

river jurisdiction - more details here;

by 1844 this special jurisdiction was dispersed, and as a result of

mergers and boundary changes the court moved to Stepney; its

present-day successor, the Thames Magistrates Court, is in Bow Road.

Patrick Colquhoun (1792-1820)

John Harriott (1792-1816)

William Bragge whose family was from Sadborow in Dorset

William Kinnaird (-1821) - at the time of his death, aged 66, he had become the senior magistrate; obituaries described him as highly respectable, though a letter to The Times in 1828 says dismissively he kept a little chemist's shop in Holborn.

John Longley (18??-22)

A merchant's son, born at Chatham in 1749, he was called to the bar at

Lincoln's Inn in 1772. A political writer, in 1784 he was appointed

Recorder of Rochester, resigning in 1803, and was appointed to the

Thames Police Court at some point later, remaining in office until his

death in 1822. The previous year saw the closure of the Shadwell

office, consequent on the 1821 Act for the more effectual Administration of the Office of a Justice of the Peace in and near the Metropolis

which took up his suggestion that magistrates should be given authority

to suspend or dismiss incompetent or corrupt parish watchmen or

patrols. (It also set a 40-year age limit on apppointment to these

offices.)

He

lived, with his wife Elizabeth (whom he married in Battersea in 1773)

and their seventeen children, at Angley House, near Cranbrook,

Tonbridge [first left - by Thomas Downes Wilmot Dearn, 1814], and then at Satis House, Boley Hill, near Rochester Castle [second left] - which now houses the administrative offices of King's School Rochester;

its name allegedly came from the comment of Queen Elizabeth I who

stayed at a previous incarnation of the house and when asked if she had

been comfortable, replied satis - OK. (Dickens knew the house, and it gave its name to Miss Havisham's house in Great Expectations.) His sixteenth child, Charles Thomas Longley, became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1862 [right].

He

lived, with his wife Elizabeth (whom he married in Battersea in 1773)

and their seventeen children, at Angley House, near Cranbrook,

Tonbridge [first left - by Thomas Downes Wilmot Dearn, 1814], and then at Satis House, Boley Hill, near Rochester Castle [second left] - which now houses the administrative offices of King's School Rochester;

its name allegedly came from the comment of Queen Elizabeth I who

stayed at a previous incarnation of the house and when asked if she had

been comfortable, replied satis - OK. (Dickens knew the house, and it gave its name to Miss Havisham's house in Great Expectations.) His sixteenth child, Charles Thomas Longley, became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1862 [right].

Captain Thomas Richbell RN (1816/17-33)

His remarkable life naval career was described in the 1833 obituary in the Gentleman's Magazine:

Captain Richbell entered the Navy at the age of nine years under the

care of his uncle, Lieut. Edward Woodnoth, and served with his present

Majesty in the West Indies. For the gallantry and bravery he displayed

in several actions and hazardous engagements, he was successively

promoted to the rank of Midshipman, Lieutenant 1780 (before attaining

his eighteenth year), Commander 1789, and Post Captain 1802. In the

year 1792 or 1793 he was appointed regulating Captain of the Volunteer

and Impressment department, in the metropolis, and to the charge of the

Enterprise tender ship off the Tower; and until the close of the war he

performed the onerous duties of his office to the satisfaction of the

government. He continued in this situation until the beginning of the

year 1817, when he was appointed by Lord Sidmouth. then Home Secretary,

to the office of a Thames police Magistrate, with the privilege of

retaining his half-pay. He has left a widow, who has been for some time

labouring under a severe indisposition, and a son and daughter under

age, to deplore the loss of a kind husband and most affectionate

father. Captain Richbell was a gentleman of very frugal habits, and his

property, which consists of freehold and leasehold estates, and money

in the funds, is said to be very considerable. Several of the

productions of his pencil have been exhibited at the Royal Academy

[of which he was an honorary member].

Capt Richbell's remains were interred on the 2d of May, in the vault

beneath the parish church of Wapping. The hearse, drawn by four horses,

was followed by three mourning coaches, containing the deceased's son,

a youth aged 15, Mr. Drinkald, a Ruler of the Waterman's Company, and

Mr. Baxter, the executors Mr. Broderip, one of the Thames Police

Magistrates, Mr. Symons, the Chief Clerk, Captain Cooke, R.N., Dr.

Hackness and Dr. Blake. |

He

succeeded

Herriott at the Thames court, and lived at Muscovy Court, Tower

Hill (a 'good' address at the time - demolished 1913-14 for the Port of

London Authority's offices). He died at his office in Wapping High

Street, aged 70. A nephew

Francis Edward Collingwood served as a midshipman with Nelson on HMS Victory.

William Ballantine (1821-48)

Called to the bar at the Inner Temple in 1813, having the previous year completed his magnum opus A Treatise on the Statute of Limitations,

his chambers were at Serjeant's Inn, Fleet Street. He became the senior magistrate of the Thames police with control over

the river police force; he died, aged 73, at Cadogan Place, Chelsea in

1852. His son William Ballantine

(1812-87), one of the last of the Serjeants-at-Law (the title was

abolished in the reforms of 1873) perhaps received the largest barrister's fee to

date in 1875 (5,000 guineas plus the same in fees) for defending an

Indian prince, Mulhar Rao, the Gaikwur of Baroda, on charge of

poisoning Colonel Phayre, the British Resident. He also acted in the

Tichbourne claimant case. His Experiences of a Barrister's Life were published the year after his death.

William John Broderip FRS &c (1822-46)

Born in 1789, eldest

son of a Bristol surgeon, he was educated locally and graduated from

Oriel College Oxford in 1812, having attended the anatomical lectures

of Sir Christopher Pegge, and the chemical and mineralogical lectures

of Dr. John Kidd. He was called to the Bar from the Inner Temple in

1817 and served on the western circuit - also editing, with Peregrine

Bingham, Reports from the Court of Common Pleas

(3 vols, 1820-22). Appointed in 1822 by Lord Sidmouth as a police

magistrate, transferring to Westminster in 1846, he continued in office

until compelled to resign because of deafness in 1856. In 1824 he had

edited the 4th edition of Robert Callis on the Statute of Sewers

(lectures first delivered in 1622 - combining his antiquarian and legal

interests). He was elected a bencher of Gray's Inn in 1850 (and

treasurer the following year), taking charge of the library.

Born in 1789, eldest

son of a Bristol surgeon, he was educated locally and graduated from

Oriel College Oxford in 1812, having attended the anatomical lectures

of Sir Christopher Pegge, and the chemical and mineralogical lectures

of Dr. John Kidd. He was called to the Bar from the Inner Temple in

1817 and served on the western circuit - also editing, with Peregrine

Bingham, Reports from the Court of Common Pleas

(3 vols, 1820-22). Appointed in 1822 by Lord Sidmouth as a police

magistrate, transferring to Westminster in 1846, he continued in office

until compelled to resign because of deafness in 1856. In 1824 he had

edited the 4th edition of Robert Callis on the Statute of Sewers

(lectures first delivered in 1622 - combining his antiquarian and legal

interests). He was elected a bencher of Gray's Inn in 1850 (and

treasurer the following year), taking charge of the library.

His great

passion was natural history, and his collection of shells, which many

foreign professors inspected in his chambers at Gray's Inn, was later

purchased by the British Museum. He was elected a fellow of the Linnean Society in 1824, of the Geological Society in 1825 (of which for a time he was Secretary), and the Royal Society in 1828; and with Sir Stamford Raffles was one of the original fellows of the Zoological Society in 1820, contributing many papers, particularly on malacology (the study of molluscs) to its Proceedings, and co-writing a guide to its gardens in 1829. Among other writings was Hints for Collecting Animals and their Products (1832), 'Account of the Manners of a Tame Beaver' (Gardens and Menagerie of the Zoological Society); Zoological Recreations (1847) and Leaves from the Note-book of A Naturalist (1852) - both collections of items for the New Monthly Magazine and Fraser's Magazine; the zoological articles in the Penny Cyclopædia

from Ast to the end (mammals, birds, reptiles, Crustacea, mollusca,

conchifera, cirrigrada, pulmagrada, &c); his last publication was

'On the Shark' (Fraser's Magazine 1859): he died, in his chambers, of apoplexy that year. Posthumously, a historical introduction to R. Owen's Memoir of the Dodo appeared in 1861.

John Beswicke Greenwood (1833-??)

Born in Dewsbury

in 1797, he was a magistrate (later chairman of the West Riding

Sessions) there as well as in London. The family home was at Moor

Bottom in that town, and they inherited the Purlwell estate. In 1842 he

arranged for William Hall, parish constable and overseer at Batley -

later

Superintendent of the West Riding Constabulary - to receive a £50

government reward for apprehending the

local leaders of the Chartist-inspired general strike, known at the Plug Riots. Isaac Binns,

a writer on dialect and borough treasurer of Batley, regarded 'old

Beswick' as responsible for the unpaved, rutted and muddy roads of

'mucky Batley'. In 1859 Greenwood published The Early Ecclesiastical History of Dewsbury.

In London, he sat at the Thames court, with Combe; at Clerkenwell from 1837 in the house of Clarkson;

and at Bow Street and Hatton Garden from 1839. His London home (with

his married sister Grace) was at 18 Woburn Square. In his 1843 evidence to the House of Lords Select Committee on Defamation and Libel he observed I

think a great deal of matter in the shape of police reports gets into

the newspapers, which must be shocking to ladies, who occasionally must

fall into it without being aware of it. He died in 1879, leaving most of his wealth to William Carr, surgeon, magistrate and antiquary.

Boyce Combe (1833-36 and Lambeth Street 1836-39)

Boyce Combe (1833-36 and Lambeth Street 1836-39)

1789-1864, one of the ten children of Harvey Christian Combe

of Cobham Park Surrey, Whig politician and MP for the City of London

and Lord Mayor 1799. Educated at Harrow, he became a bencher of Gray's

Inn, and was appointed to the Thames Police Court in 1833, in the house of the late Capt. Richbell, and then to Lambeth Street in 1836, in the house of the late Thomas Walker, and then to Hatton Garden in 1839. In 1815 he married a cousin Caroline,

sole heiress of the Revd Evan Jones of Trewythen, Montgomery, an old

Welsh family (she died in 1881). Their family lived at Hill House,

Speltham Hill, Hambledon, Hampshire (listed Grade II in 1987); he was a

member of the Athenæum and Reform Clubs, with a London address at 43

Upper Seymour Street. See here for a case of 1838 involving speed limits on the Thames. In R. v. Boyce Combe and the Churchwardens of St Andrew Holbon ex parte Loader (1849) QB 11 (NS) 179

the Queen's Bench considered a case where churchwardens had refused to

make a payment of 20s. to Loader, keeper of the 'second engine', for

attending a fire, under sections 76 and 77 of the Fires Prevention (Metropolis) Act 1774.

They argued that they had discretion to make a payment for this amount

or to set another figure, and had declined to do either because there

were at that time a number of wasteful rewards being paid; and Combe

argued that he had no jurisdiction to order payment unless it was

originated by the wardens. The law was unclear, but the three judges

held that the magistrate did have discretion to set and sanction a

payment.

His son, Major Boyce Harvey Combe of Oaklands, Battle, Sussex, a cavalry

officer in the Honourable East India Company cavalry and Major Commanding 1st Battalion Cinque Ports

Rifle Volunteers, became a JP for Sussex.

Thomas Clarkson (1836-37)

The only son of the famous Thomas Clarkson,

nonconformist anti-slavery campaigner (1760-1846), he was born in

Whitby, and educated at Bury St Edmunds and Trinity College Cambridge,

and called to the bar at the Middle Temple. He became a pleader on the

northern circuit, and - like a number of others of the period - a

'revising barrister', reviewing and adjudicating on electoral registers

in the wake of extensions of the franchise in 1832. He was kept busy in

Leeds, with over 4,000 objections, and determined that the non-payment

of the one shilling registration fee was not a disqualifying factor.

(Around this time, fellow-revisers determined, among other things, that

the franchise extended to dissenting ministers if they held lifelong

appointments; to dissenting trustees who received pew rents; and to

those who held a freehold right to pews in parish churches under an Act

of Parliament, but not others.) When the great theologian Frederick Denison Maurice

resolved to deal with his doubts about ordination (rejecting the narrow

Unitarianism of his father but troubled by the requirements of Anglican

subscription) by training as a barrister, at Trinity Hall Cambridge and

in London, Thomas Clarkson offered him a free pupillage. He was a

friend of Charles Lamb and his sister Mary Lamb (literary associates of Coleridge and

Wordsworth) and features in their letters. Appointed to succeed Combe

in 1836, he was killed in carriage accident the following year, aged 40.

Five of the following justices were appointed from the Oxford circuit.

Edward Yardley (1846-60)

The eldest son

Edward Yardley of Shrewsbury, he was born in Paley, Shropshire in 1804.

After Shrewsbury School, he went to Magdalen College Cambridge, where

he was the 40th and last wrangler

and a Fellow from 1830-2; in that year he married Elizabeth Taylor of

Everley, near Scarborough. Admitted to the Bar at Lincoln's Inn in

1834, he was appointed a stipendiary magistrate in 1846, moving four

years later to Marylebone to fill the vacancy caused by the death of

Isaac O. Seeker. (There he was a member of the parish vestry, and

became embroiled in a long-standing antipathy with the assistant

overseer of poor relief.) It is said that his decisions on river law

were scarcely ever challenged: one example of this jurisdiction is his

involvement in 1856 over the collision of the Josephine Willis and the Mangerton steamer. He gave evidence to the Select Committee on Poor Law Relief in 1861.

He was the elder

brother of Sir William Yardley (1810-78), of the Middle Temple, who was

made a puisne judge of the Bombay supreme court in 1847, was knighted,

and became chief justice 1852-58; on his return to England he was an

unsuccessful parliamentary candidate, and died in 1878. And he was the

father of Edward, also of the Middle Temple, who practised for a time

in Bombay alongside his uncle (and was clerk of the insolvent debtors'

court). It was to the son, rather than the father (contrary to the

claims of one source) that Charles Dickens wrote in 1868, acknowledging

the receipt of a package of books, since Edward died at his home at 8

Blandford Square in 1866 after a long illness.

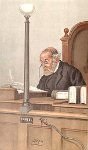

Sir James Taylor Ingham (1850s)

Sir James Taylor Ingham (1850s)

Born in Mirfield, West Yorkshire in 1805, younger son of

Joshua Inham of Blake Hall, he attended school in Richmond, Yorkshire,

and Trinity College Cambridge. After his time at the Thames Court in

the 1850s, he became chief magistrate of Bow Street. Right is Sir Leslie Ward's Vanity Fair

cartoon of 1886, and an illustration for The Graphic in 1890 - the year of his death.

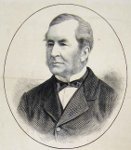

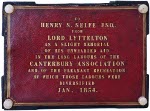

Henry Selfe Selfe [sic] 1856-63

Born at Rose Hill, near Worcester, in 1810, he changed his surname from

Page to inherit his maternal grandmother's property at Trowbridge,

Wiltshire. He studied at Glasgow University and was called to the Bar

in 1834, practising on the Oxford circuit and the Parliamentary Bar

until his appointment to the Thames Court in 1856. Here he was

associated with Colonel ffrench and Aspinall Turner on the Weedon Commision

inquiring into the state of the Army Clothing Department and

defalcations in war stores sent to the Crimea. He transferred to the

Westminster Court in 1863 until his death in 1870, from chronic gout.

He was said to be astute and fair-minded, leavening his judgements with

common sense and wit. He was a governor of Rugby School.

In 1840 he married Anna Maria, eldest daughter of William Spooner,

Archdeacon of Coventry and Rector of Elmdon, near Rugby; her sister

married Archibald Tait, who was Bishop of London at the time of the

Ritualism Riots

at St George-in-the-East and later became became

Archbishop of Canterbury. (In 1860 he tried at least two of the cases for disturbance that came before his court - nowadays he would probably be expected to declare an interest and recuse himself.nowadays he would have been expected to recuse

himself because of a personal connection - compare Dame Elizabeth Butler-Sloss

standing down from the 'historic' child abuse enquiry in 2014 because

her late brother, Lord Havers, had been Attorney-General at the time

when key decisions were made. But such scruples did not apply then.) They lived at 15 St George's Square [West,

rather than East, End!] and had three daughters and four sons

(one of whom, Sir William Lucius Selfe (1845-1924) became a county

court judge and was for a time the principal Secretary to Lord Cairns,

the Lord Chancellor).

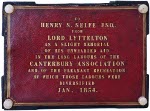

Selfe was active in the Canterbury Association, promoting settlement to New Zealand (where another son, James, went to live; another relative, Charles Henry Selfe Matthews (1873-1961), was a priest serving with the Bush Brotherhood in Australia in the early years of the next century). Right is a presentation casket from Lord Lyttleton of 1854. He

used his contacts and knowledge of the principal settlers to help the

colony get established. He became honorary London agent for the

Provincial Government, but resigned in 1866 because he felt compromised

by misinformation about a railway loan, whereupon he was given an

honorarium of £500 by the government, with which he bought a plot of

100 acres at Heathcote, travelling out to Canterbury with Lord

Lyttleton in 1866-67. He was a director of the London Board of the New

Zealand Trust and Loan Company. He had hoped to be appointed to a

judgeship there, and there is much correspondence on the matter, but Henry Barnes Gresson was appointed instead.

Selfe was active in the Canterbury Association, promoting settlement to New Zealand (where another son, James, went to live; another relative, Charles Henry Selfe Matthews (1873-1961), was a priest serving with the Bush Brotherhood in Australia in the early years of the next century). Right is a presentation casket from Lord Lyttleton of 1854. He

used his contacts and knowledge of the principal settlers to help the

colony get established. He became honorary London agent for the

Provincial Government, but resigned in 1866 because he felt compromised

by misinformation about a railway loan, whereupon he was given an

honorarium of £500 by the government, with which he bought a plot of

100 acres at Heathcote, travelling out to Canterbury with Lord

Lyttleton in 1866-67. He was a director of the London Board of the New

Zealand Trust and Loan Company. He had hoped to be appointed to a

judgeship there, and there is much correspondence on the matter, but Henry Barnes Gresson was appointed instead.

Like

Lord Lyttleton (who was president of the British Chess Association), he

was a chess player, and involved in the establishment and running of

the Westminster Chess Club, formed in the 1860s when the Cigar Divan

was converted into a dining room. A correspondent of 1873 to the Westminster Papers comments

... The Divan was thirty years old. It was known to and visited by all the

Chess world. It was one of the sights of London, and the admission was

but sixpence. The establishment was well conducted, and the members

behaved as gentlemen. The Divan being converted into a Dining room, and

the Chess room provided in its place not giving the accommodation that

the Chess players expected, they resolved to start a Club. The starting

a Club necessitated Whist, and Whist, containing the element gambling,

smothered Chess; so much so that, unless an effort of some sort be made

to revive Chess, the Club as a Chess Club will cease to exist. I am not

at all sure that it is advisable to attempt this revival, because, with

all deference to such as you who support Chess with your purse and

brains, the professional Chess players have been much too pampered ever

to have a healthy existence. I think it would be much better to let

Chess alone until the Chess players find their own level. The Club

still has amongst its members some of our most brilliant players; but

as my letter is for the Whist department, I daresay you will think I

have said more than enough on this subject ... [Left is an 1855 illustration of Lyttleton and other chess players.] ... The Divan was thirty years old. It was known to and visited by all the

Chess world. It was one of the sights of London, and the admission was

but sixpence. The establishment was well conducted, and the members

behaved as gentlemen. The Divan being converted into a Dining room, and

the Chess room provided in its place not giving the accommodation that

the Chess players expected, they resolved to start a Club. The starting

a Club necessitated Whist, and Whist, containing the element gambling,

smothered Chess; so much so that, unless an effort of some sort be made

to revive Chess, the Club as a Chess Club will cease to exist. I am not

at all sure that it is advisable to attempt this revival, because, with

all deference to such as you who support Chess with your purse and

brains, the professional Chess players have been much too pampered ever

to have a healthy existence. I think it would be much better to let

Chess alone until the Chess players find their own level. The Club

still has amongst its members some of our most brilliant players; but

as my letter is for the Whist department, I daresay you will think I

have said more than enough on this subject ... [Left is an 1855 illustration of Lyttleton and other chess players.]

|

See here

for a chess champion who was curate at St George-in-the-East in 1866.

Lord Lyttleton committed suicide in 1876 following bouts of insanity.

Edmund Humphr(e)y Woolrych (1862-64)

The

eldest son of Josiah Woolrych and an Italian mother, of

Monastier, in Lombardy, and from a family which produced several

lawyers (a relative Humphry William Woolrych

was a Serjeant-at-Law and a prolific writer of legal textbooks), he was

called to the Bar at the Middle Temple in 1839. Prior to his

appointment as a magistrate, he played a key role in the early years of

the Metropolitan Board of Works, created by Sir Benjamin Hall's Metropolis Local Management Act

of 1855 (later revised). It started with a staff of about 50 and an

annual wage bill of £25,000, but this increased markedly. The Board

itself had 45 members, elected from the various vestries (unpaid), and

was efficiently chaired for fifteen years by Sir John Thwaites, a Strict and Particular Baptist

from Westmorland but who had adapted to 'London ways' (and was paid,

something between £1000 and £2000 a year), and had an outstanding

engineer in the famous Joseph Bazalgette.

But - partly because (although its offices were at the former

Commissioners of Sewers premises in Greek Street) its meetings were

held in the Guildhall, with many members of the public in the gallery -

the workings of what was variously dubbed the 'Senate of Sewers',

'Parliament of Parishes' or 'Metropolitan Board of Words' tended to be

long-winded; and it later became open to charges of corruption.

Woolrych was one of 22 candidates for the post of clerk - he had been

secretary to the extinct Metropolitan Commissioners of Sewers; regarded

as a 'City man', but was, in the view of one commentator, a clerk of signal ability, who read his minutes with dispatch and paid close attention to debates.

Within four years he proposed that he should be appointed Legal Adviser

and Standing Counsel, and despite protests, this was done, at a salary

of £800. He had a point: drainage and street improvement schemes were

mounting in number and complexity, and when he moved on in 1861 the

Metropolitan Board of Works created a separate legal department, headed

by a solicitor. See further David Edward Owen The

Government of Victorian London, 1855-1889: The Metropolitan Board of

Works, the Vestries, and the City Corporation (Harvard 1982), and

Woolrych's own work The Metropolis Local Management Acts,

with introduction, notes and an appendix, containing statues

incorporated with the Metropolis Local Management Act 1855 or relating

to the functions fo the boards and vestries thereby constituted (Shaw & Sons 1863).

He

moved on to the Southwark court (and was replaced here by John Paget)

- giving evidence on the Sale of Liquors on Sunday Bill 1868 -

and then to Westminster; on leaving that post in 1880 he was made a JP

for Middlesex.

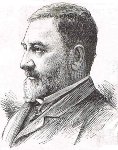

William Partridge (1863-69)

Born in 1818, the eldest son of John Partridge of Bishop's Wood,

Ross-on-Wye, Hereford, he attended Winchester College and was called to the Bar at

the Middle Temple in 1843 (though previously studied at Lincoln's Inn).

Two years earlier he

married Elizabeth Emily Webb, daughter of a Herefordshire magistrate.

He worked on the Oxford circuit before appointment as a stipendiary

magistrate in Wolverhampton in 1860, and tranferred to the Thames Court

in 1863. He moved on to Southwark, and then Marylebone; the

illustration right

is from the year of his death, 1891. Their London home was at 49

Gloucester Place, Hyde Park (his club was the Oxford & Cambridge),

and in Hereford at Wyelands (a large house built in the 1820s), near

Ross on Wye. Far right is a (much later) sign from their local station, Walford on the Ross and Monmouth Railway,

opened in 1873, of which he was a director. His eldest son Richard William was a barrister of the

Middle Temple, and a grandson R. Cecil Partridge became manager of the Central London Railway, aka the 'twopenny tube', which soon after became part of the Central Line.

Born in 1818, the eldest son of John Partridge of Bishop's Wood,

Ross-on-Wye, Hereford, he attended Winchester College and was called to the Bar at

the Middle Temple in 1843 (though previously studied at Lincoln's Inn).

Two years earlier he

married Elizabeth Emily Webb, daughter of a Herefordshire magistrate.

He worked on the Oxford circuit before appointment as a stipendiary

magistrate in Wolverhampton in 1860, and tranferred to the Thames Court

in 1863. He moved on to Southwark, and then Marylebone; the

illustration right

is from the year of his death, 1891. Their London home was at 49

Gloucester Place, Hyde Park (his club was the Oxford & Cambridge),

and in Hereford at Wyelands (a large house built in the 1820s), near

Ross on Wye. Far right is a (much later) sign from their local station, Walford on the Ross and Monmouth Railway,

opened in 1873, of which he was a director. His eldest son Richard William was a barrister of the

Middle Temple, and a grandson R. Cecil Partridge became manager of the Central London Railway, aka the 'twopenny tube', which soon after became part of the Central Line.

John Paget (1864-??)

Born in 1811 in Humberstone, Leicestershire, he was the son of banker

(Pares, Paget & Co in Leicester) and Whig (Liberal) politician Thomas Paget,

who was the first Mayor of the reformed Coropration of Leicester and

briefly MP for the county before the constituency was divided in 1832. Another son Thomas Tertius - with whom he had a bitter feud over their father's substantial estate - and John's own son Thomas Guy (heir of his childless uncle Thomas Tertius)

also served as Leicestershire MPs. John wrote some election material in support of his father's activities.The family were of Huguenot origin, descended from Valerian Paget who fled to England after the St Bartholomew's Day Massacre in France in 1572.

In 1834 John

married Elizabeth Rathbone, from a Liverpool Unitarian family active in

social reform - her brother and his daughter were both MPs. He joined the Reform Club when it was founded in 1836, and was a member of its library committee for 24 years and chairman from 1861-65. He was

called to the Bar in 1838 and served as secretary to Lord

Chancellors Truro and Cranworth from 1850-55, becoming a stipendiary

magistrate in 1864, succeeding John Paget when he transferred to Southwark.

Living at some points in and around Euston Square, but mainly at

23 The Boltons in West Brompton, John and Elizabeth had a son and two daughters, one of

whom was Dame Mary Rosalind Paget

(1855-1948), a nursing sister and campaigner for midwifery registration

and reform [which began with the 1902 Midwives Act], who was the first Superintendent, later Inspector General,

of the Queen's Jubilee Institute for District Nursing at the London

Hospital. He died in 1898. There

is more about the family's political involvement in the second half of this paper by R.H. Evans, including discussion of a letter from John to Guy.

From 1860-88 he wrote regularly for Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine.

His articles criticizing Macaulay's views of Marlborough, the massacre

of Glencoe, the highlands of Scotland, Claverhouse, and William Penn,

were reprinted as The New Examen (1861). Other articles on a wide range

of topics, including Nelson, Byron, well-known legal cases, and art,

appeared as Paradoxes and Puzzles: Historical, Judicial,

and Literary (1874). He was also a skilful draughtsman, and his illustrations to Edward Fordham Flower's Bits and

Bearing-Reins (1875) helped to show the cruelty to horses caused by this method of harnessing [example right].

The Pagets moved in artistic circles, and Elizabeth's collection of

family papers (now in the National Archive) includes letters to and

from well-known artists of the day.

From 1860-88 he wrote regularly for Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine.

His articles criticizing Macaulay's views of Marlborough, the massacre

of Glencoe, the highlands of Scotland, Claverhouse, and William Penn,

were reprinted as The New Examen (1861). Other articles on a wide range

of topics, including Nelson, Byron, well-known legal cases, and art,

appeared as Paradoxes and Puzzles: Historical, Judicial,

and Literary (1874). He was also a skilful draughtsman, and his illustrations to Edward Fordham Flower's Bits and

Bearing-Reins (1875) helped to show the cruelty to horses caused by this method of harnessing [example right].

The Pagets moved in artistic circles, and Elizabeth's collection of

family papers (now in the National Archive) includes letters to and

from well-known artists of the day.

Following the publication of James Greenwood A Night in the Workhouse in the Pall Mall Gazette

(1866) and associated dramas, there was a spate of prurient middle

class fascination with workhouse life and its 'hideous enjoyments', and

two cases of people who had presented themselves at workhouses but had

money in their pockets (in breach of the rules) came to court. In the

first, which he claimed was a drunken spree, David Greenall was

released from Marlborough Street Police Court with a severe caution;

but in the second, heard by Paget at the Thames Police Court, a woman

ostentatiously arrived by cab at the Mile End Workhouse demanded

lodging in the casual ward, claiming that the Poor Law Board

regulations required them to take in all who claimed admission. She was

found to have 17s 7½d on her; and Paget sentenced her to a month's

hard labour in prison, exciting much press comment. (She

does not appear to have been a serious investigator of conditions,

unlike the 'destitute but once respectable' widow hired by medical

reformer Dr J.H. Stallard that same year to report on her findings at

four casual wards, including St George-in-the-East and Whitechapel,

which she did without titillation, but with terror of the ubiquitous

vermin, and convinced that cholera was generated every night - text here.)

But the previous year, according to Punch, he had been very kind as usual, and only bade her move on, when a well dressed young woman was charged with being tipsy and incapable of taking care of herself:

The

prisoner, who was attired in hat and feathers, a lace veil of fine

texture, a Paisley shawl worth at least four guineas, and a superb

flounced black silk dress said the unfortunate condition she was in was

all owing to the Underground Railway.

Mr Paget: What do you mean?

The Prisoner said she paid a visit to her brother and his wife

yesterday at Paddington and proceeded there and back by the Underground

Railway, which had such an effect upon her that sho became insensible.

Mr Paget: You were intoxicated.

Prisoner: Yes, I had one glass of gin, no more, after leaving the Underground Railway. I will never take any more.

Mr Paget: What are you?

Prisoner: A policeman's wife. He has been twenty years in the force. Oh,

Sir, it is all owing to the Underground Railway [Laughter].

|

A case where he sought to be helpful was reported in the Shipping Gazette, July 29, 1864:

George La Pierre, a seaman, came before Mr. Paget, at the Thames Police

Court, on Thursday, for redress under very singular circumstances. He

went out in the English ship Universe

to New York. One day he went on shore in New York with the third mate,

who got tipsy and made a noise. He was leading the third mate along

with the intention of returning to their ship when the Police

interfered, and took the third mate into custody and locked him up for

making a noise. At the same time several runners and crimps attacked

him and beat him, and having overpowered him took him to a house where

they kept him a close prisoner all night, and in the morning forced him

on board the American ship Caroline Nasmyth.

He was compelled to remain on board by the Captain and chief mate, to

whom he represented that he was the boatswain of the Universe, was

afflicted with a bad leg, and unable to do any hard work. The Captain

said he did not care about his leg, and that all he wanted was his

body; that he had paid men to bring him on board, and that he must work

on the voyage to England. He arrived in the Victoria Dock on Wednesday,

and asked for wages for his services. The Captain refused to pay him

anything, and he had now come on shore to seek redress and compensation

for a gross act of injustice and oppression.

Mr. Paget asked the applicant if he had signed any articles of agreement on board the Caroline Nasmyth,

to which he answered in the negative, and said he had no other clothes

but what he stood upright in. He came across the Atlantic Ocean without

a change of clothes and linen. In answer to further questions by the

magistrate, the applicant said all his clothes were on board the Universe, which had arrived at Liverpool. His wife had applied for his chest, hammock, and clothing on board the Universe,

at Liverpool, and the reply of the Captain was that he knew nothing

about them. Mr. Paget could not help thinking it was a very hard case

on the man. He was afraid he could not interfere in the matter. If the Caroline Nasmyth

was an English ship he would grant a summons for wages. He had no

jurisdiction over American ships. With regard to the clothes on board

the Universe he would

recommend La Pierre to write to his wife at Liverpool and direct her to

apply to Mr. Raffles, the stipendiary magistrate there, who would

render every possible assistance. The Applicant: What am I to do here?

I have no means of living, and no money. Mr. Paget advised the seaman

to wait on the American Consul and represent his grievances to him. The

seaman then left, and at 5 o'clock returned and said the American

Consul refused to give him any redress, and only laughed at him. The

consul threatened to have him arrested and sent back to the Caroline Nasmyth

again. Mr. Paget said that could not be done, and he would take care

the sailor was not arrested or kidnapped in his own country. He

directed Howland, a police constable, No. 89 H, who is attached to the

court, to take charge of the seaman, to provide him with food and a

lodging, and to make very particular inquiries into all the

circumstances of the case, and report to him the result. The applicant

then left with the officer. |

Ralph

Augustus Benson (?1867-69)

Born

in Hanley in 1828, son of Moses George Benson of Lutwyche Hall, near

Wenlock (the family home from the start of the 19th century - left), whose

grandfather Moses was a Liverpool merchant, probably involved in the

slave trade, and whose father Ralph was MP for Stafford. His

mother Charlotte Riou Browne was a

descendant,

several generations

back, of Mathieu Riou, member of the protestant congregation of

Vernoux in eastern France.

Ralph studied

at Christ Church, Oxford,

and was admitted to the Bar, practising in the Oxford circuit. He

stood unsuccessfully as a

Tory

candidate for the Wrekin Division of Shropshire,

and also for Reading..

Born

in Hanley in 1828, son of Moses George Benson of Lutwyche Hall, near

Wenlock (the family home from the start of the 19th century - left), whose

grandfather Moses was a Liverpool merchant, probably involved in the

slave trade, and whose father Ralph was MP for Stafford. His

mother Charlotte Riou Browne was a

descendant,

several generations

back, of Mathieu Riou, member of the protestant congregation of

Vernoux in eastern France.

Ralph studied

at Christ Church, Oxford,

and was admitted to the Bar, practising in the Oxford circuit. He

stood unsuccessfully as a

Tory

candidate for the Wrekin Division of Shropshire,

and also for Reading..

In

1867 he refused to make a conviction based on the evidence of a

ten-year old girl, although it was given in a

very clear and straightforward manner, and with an appearance of

great truth, since it was uncorroborated, and

a second girl who was present had not come forward, despite the case

being twice adjourned; furthermore, he had before him the character

witness of the incumbent of a large parish,

who had known the prisoner five years, and spoke of him as a well

conducted, respectable, and moral man.

Recognising that his action might be regarded as controversial

(because the evidence of a single witness was normally sufficient),

he said he hoped he was not doing wrong in the step he was about to

adopt. Punch

commented favourably on this remark: The really worthy

Magistrate may make up his mind on that point. He was not doing wrong

in refusing to convict on evidence which, whether true or false, was

insufficient. He was doing right. In so doing he certainly did what

was, as aforesaid, a very extraordinary thing, but will be, let us

hope, in good time an ordinary thing, as it will whenever Magistrates

in general get accustomed invariably to weigh evidence by the

standard of reason and justice. Mr Benson has shown them how to use

the scales.

In

1869, according to the Daily News and The Times, Constable William

Smith was dismissed from the force and sentenced by Benson to a

month's hard labour for using excessive force in protecting a woman

abused by her husband - John Stuart Mill noted this case in

correspondence.Benson

was transferred to Southwark (working alongside William Partridge) on

the appointment of Sir Franklin Lushington.

In

1869, according to the Daily News and The Times, Constable William

Smith was dismissed from the force and sentenced by Benson to a

month's hard labour for using excessive force in protecting a woman

abused by her husband - John Stuart Mill noted this case in

correspondence.Benson

was transferred to Southwark (working alongside William Partridge) on

the appointment of Sir Franklin Lushington.

He

married Henrietta Cockerell in 1860 and they had three sons and two

daughters,

to one of whom, at St Peter Easthope in Shropshire (the local church of

Lutwyche Hall, rebuilt in Arts and Crafts style after a fire in 1928)),

there is a window in the chancel of 1933 [right] by the famous firm of Kempe (which closed the following year): In honour of Our Lord Jesus Christ, the King

of Martyrs, and of His Apostle St. Philip who suffered martyrdom on

the Cross, this window is dedicated as a memorial to Philippa Jessie,

daughter of Ralph Augustus Benson of Lutwyche, by George Reginald

Benson. A.D. mcmxxxiii.

He

was a member of Marylebone Cricket Club: his 'career' details are

here. He

contracted smallpox in 1871 but recovered, living until 1886 when he died in Marylebone.

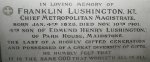

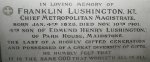

Sir Franklin Lushington (1869-90)

Franklin (1822-1901) was the fourth

son of the 13 children of the Hon Edmund Henry Lushington, who among

other judicial posts was puisne judge of the Court of Ceylon (and whose

father was a well-known barrister). There were other lawyers in the

family, but ironically his older brother Edmund (1811-93), who was given the

middle name 'Law', was not one of them - he became a Professor of Greek

and Rector of Glasgow University. Franklin was named for a

distinguished naval captain ancestor of the previous century. He was a

pupil of Thomas Arnold at Rugby - one of the last, along with the Dean

of Westminster, to survive into the 20th century. After Trinity College

Cambridge, where he held scholarships and was a medal-winner,

graduating in 1846. he was called to the Bar at the Inner Temple in

1853. A spell in the diplomatic service brought him an

appointment from 1855-58 to the Supreme Council of Justice of the Ionian Islands

which were under British rule from 1815-62 - Bulmer Lytton, Secretary

of State for the Colonies, appointed him; Sir George Bowen was the

Governor; and Gladstone was for a time the High Commissioner, who

recommended that rule of the islands should be returned to Greece. Like

other lawyers, he did not feel specifically called to 'serve' abroad,

and not keen to leave home, but

it is necessary to have some definite work to do in place of the

prospect of spending the best years of one's life at home doing little

or nothing - a prospect common to most pursuers of the English bar at

the present (1855, to Whiiliam Whewell).

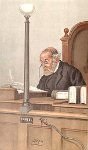

In 1869 he became a metropolitan magistrate, with the Thames Police

Court as his first appointment, where he sat until 1890 (on a stipend

of £1500 a year), when he was transferred to Bow Street (the Central

Criminal Court), becoming chief magistrate - and knighted - in 1899

until his sudden death two years later. He was described as quiet and severe, and as fair and impartial; The Sketch said he would be remembered for his

capacity for giving the closest attention to every case, trivial as

some might be, and for a uniform kindliness towards all. [Right is

his memorial at St Mary Boxley, near Maidstone, and nearby Park House,

the family home: Tennyson had lived here for a time in 1841 when his

sister married into the family.]

In 1869 he became a metropolitan magistrate, with the Thames Police

Court as his first appointment, where he sat until 1890 (on a stipend

of £1500 a year), when he was transferred to Bow Street (the Central

Criminal Court), becoming chief magistrate - and knighted - in 1899

until his sudden death two years later. He was described as quiet and severe, and as fair and impartial; The Sketch said he would be remembered for his

capacity for giving the closest attention to every case, trivial as

some might be, and for a uniform kindliness towards all. [Right is

his memorial at St Mary Boxley, near Maidstone, and nearby Park House,

the family home: Tennyson had lived here for a time in 1841 when his

sister married into the family.]

An example of a 'trivial' case was a dispute in 1877 between members of a group known as the 'Social Trumps' - settle it among yourselves,

he told them. But he was involved in many high-profile criminal trials

- including, at the time of his death, the prosecution of Dr Frederick Edward Trangott Krause on charges of high treason and incitement to murder, in relation to the Boer War.

He was jealous of the reputation of the police: Sir Leslie 'Spy' Ward (the caricaturist of Vanity Fair - image left, 1899)

provided the strapline 'He Believes in the Police'. When evidence

conflicted, he almost invariably accepted the police version, once

remarking I have had occasion for

many years to listen closely to evidence given by ihe police concerning

the persons they are brought into contact with. As compared with, other

witnesses they are, in nine cases out of ten, least likely to have made

a mistake, for it is part of their duty to cultivate a habit of

observation. But there were occasions when he dealt harshly with police defaulters.

He was jealous of the reputation of the police: Sir Leslie 'Spy' Ward (the caricaturist of Vanity Fair - image left, 1899)

provided the strapline 'He Believes in the Police'. When evidence

conflicted, he almost invariably accepted the police version, once

remarking I have had occasion for

many years to listen closely to evidence given by ihe police concerning

the persons they are brought into contact with. As compared with, other