Policing, Magistrates' and other courts

The Metropolitan Police

The Metropolitan Police| north

along the City of London boundary to Hackney Road, east to White

Street, south through Charles Street into New Road, Cannon Street Road,

Old Gravel Lane to the riverside at Wapping, then westwards to the Tower

of London and back along the City Boundary. |

|

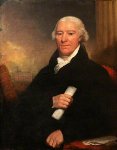

Marine Police It also took in both the policing and judicial functions of the Marine Police Office, whose origins and early history are described in detail here. All magistrates had jurisdiction over offences on or connected to the Thames, under the colloquially-known 1761 Bumboat Act, which authorised searches of all small vessels on the river, which were required to be registered with Trinity Corporation. Until the Docks were built, in the early years of the 19th century, goods were transferred to and from shore in small vessels, and all involved in this traffic - 'lumpers' (as dock labourers were known), coal-heavers, lightermen, customs officers, tidewaiters and even ratcatchers - were notoriously implicated in widespread pillage, justified as 'custom', amounting to about £½m a year on a turnover of £60m. But the magistrates were inhibited, by lack of resources or diligence, from addressing this huge challenge. In 1796 Patrick Colquhoun LLD (1745-1820), one of the first appointed stipendiary magistrates under the 1792 Act - though he never drew his stipend - proposed, in his influential Treatise on the Police of the Metropolis [several editions - the link is to that of 1806], the establishment of a system combining policing and judicial functions. In 1798, backed by West India Dock merchants and others, this came about, and was regularised in 1800 by an Act for the More Effectual Prevention of Depredations on the River Thames, with a further Act in 1821 - some details here (though little local notice was taken of this later Act, apart from its abolition of the Shadwell Police Office).  Colquhoun - left is his portrait in

the Marine Police Museum - was the 'Glasgow trader' mentioned by Sir Robert Peel (in fact he was awarded a Doctor of Laws degree by Glasgow University in 1797) was an

honourable exception to the corruption of the magistracy discussed below: he was able and public-spirited,

confining himself to police work (shunning the Brewster Sessions which, like the Fieldings, he found morally dubious). Prior to 1792 he served as a magistrate

for Middlesex, Surrey, Kent, Essex, the City and Liberty

of Westminster, and the Liberty of the Tower of London [before the

latter jurisdiction was abolished].

Post-1792, he sat at Worship Street until 1797, and later at Queen

Square, Westminster as well as at the Marine Office. He used his

influence to get the Marine Police scheme established, and

was its superintendent magistrate. Colquhoun - left is his portrait in

the Marine Police Museum - was the 'Glasgow trader' mentioned by Sir Robert Peel (in fact he was awarded a Doctor of Laws degree by Glasgow University in 1797) was an

honourable exception to the corruption of the magistracy discussed below: he was able and public-spirited,

confining himself to police work (shunning the Brewster Sessions which, like the Fieldings, he found morally dubious). Prior to 1792 he served as a magistrate

for Middlesex, Surrey, Kent, Essex, the City and Liberty

of Westminster, and the Liberty of the Tower of London [before the

latter jurisdiction was abolished].

Post-1792, he sat at Worship Street until 1797, and later at Queen

Square, Westminster as well as at the Marine Office. He used his

influence to get the Marine Police scheme established, and

was its superintendent magistrate. The resident magistrate (who had

worked unsuccessfully on a similar scheme with his relative and

fellow-magistrate John Staples, appointed to Whitechapel in 1792), and through his association with Colquhoun is now

honoured as

a co-founder of the service - he was certainly very assertive of the

role he played in it - was John Harriott (1745-1817) - right. Active until his death in 1816, when he was stricken by

cancer and died of self-inflicted stab wounds, Harriott had an eventful

life:

three times married, he served in the Royal Navy, the Merchant Navy,

and with the East India Company (where for a time he served as a kind

of chaplain, though was not ordained); he then developed farming in his

native Essex and served as a magistrate for that county; when fire

destroyed his farm, he emigrated briefly to America; on his return, he

lived in Prescot Street (later moving to Spitalfields), and took out four patents for pumping (for which he set up a small factory) and

other equipment. In 1809 clerks in the office brought charges of

'maladversion' against him, and it was agreed that for the reputation

of the force he should face them, in a King's Bench trial. He was

acquitted of all but a minor technical charge about documentation, but

the experience hit him hard. The resident magistrate (who had

worked unsuccessfully on a similar scheme with his relative and

fellow-magistrate John Staples, appointed to Whitechapel in 1792), and through his association with Colquhoun is now

honoured as

a co-founder of the service - he was certainly very assertive of the

role he played in it - was John Harriott (1745-1817) - right. Active until his death in 1816, when he was stricken by

cancer and died of self-inflicted stab wounds, Harriott had an eventful

life:

three times married, he served in the Royal Navy, the Merchant Navy,

and with the East India Company (where for a time he served as a kind

of chaplain, though was not ordained); he then developed farming in his

native Essex and served as a magistrate for that county; when fire

destroyed his farm, he emigrated briefly to America; on his return, he

lived in Prescot Street (later moving to Spitalfields), and took out four patents for pumping (for which he set up a small factory) and

other equipment. In 1809 clerks in the office brought charges of

'maladversion' against him, and it was agreed that for the reputation

of the force he should face them, in a King's Bench trial. He was

acquitted of all but a minor technical charge about documentation, but

the experience hit him hard.See here for details of its other magistrates. |

|

|

They were not routinely armed (nor did they carry the

cutlasses with which they were issued), but firearms were available for

serious incidents. As

well as constables, there were detectives: here

is an account of H division in 'Ripper times', and right a picture of its detective

team at that time.

They were not routinely armed (nor did they carry the

cutlasses with which they were issued), but firearms were available for

serious incidents. As

well as constables, there were detectives: here

is an account of H division in 'Ripper times', and right a picture of its detective

team at that time.| Shocking Nuisance. — Yesterday no less than 25 wretched females, some of whose ages did not exceed 16, and others of whom appeared to verge upon 30, and even 60, were brought before the sitting magistrate (Mr. Davies) charged with being idle, disorderly, and profligate characters. The cases of these wretched females exhibited a melancholy picture of the increase of vice and depravity in the quarter from whence they were brought in custody, namely that of Whitechapel and its neighbourhood. That quarter, it appeared, had for a considerable time past, become a scene of continued riot, disorder, profligacy and robbery; and this had increased to so alarming a degree that the inhabitants of High-street, Whitechapel, found it necessary to form themselves into a body in order to patrole [sic] the streets, and to remove the evil in question. Some of the most respectable individuals attended to prove these facts, and stated that the system of plunder and depravity at present exercised by the increasing number of prostitutes, was such as to prevent all peace in the neighbourhood, and to subject their wives and families to every species of depravity and nuisance. The prisoners were each sentenced to imprisonment for short periods in the house of Correction. |

Jane Alsop deposed that she had answered the door of her

father's house to a man claiming to be a police officer: For God's

sake bring me a light, for we have caught Spring-heeled Jack here in

the lane. She brought him a candle, and noticed that he wore a large

cloak, which he then threw off, and presented a most hideous and

frightful appearance, vomiting blue and white flame from his mouth

while his eyes resembled red balls of fire. She said he wore a large

helmet and that his clothing, which appeared to be very tight-fitting,

resembled white oilskin. He then caught hold of her and began tearing

her gown with claws which she was certain were of some metallic

substance. She screamed for help, and managed to get away from him and

ran towards the house. He caught her on the steps and tore her neck and

arms with his claws. She was rescued by one of her sisters, after which

her assailant fled. Eight days later, Lucy Scales and her sister were

returning home after visiting their brother, a butcher who lived in a

respectable part of Limehouse. As they passed through Green Dragon

Alley, they saw someone standing in an angle of the passage; he

approached her, wearing a large cloak and spurted a quantity of blue

flame in her face, temporarily blinding her and causing violent fits

which lastested several hours. Her brother, hearing the screams, ran to

her aid. Her sister reported that the attacker was tall, thin, of

gentlemanly appearance, wore a cloak and was carrying a lantern

similiar to the bull's eye lantern carried by policemen; he did not attack her, but walked away.

No-one was ever found. Jane Alsop deposed that she had answered the door of her

father's house to a man claiming to be a police officer: For God's

sake bring me a light, for we have caught Spring-heeled Jack here in

the lane. She brought him a candle, and noticed that he wore a large

cloak, which he then threw off, and presented a most hideous and

frightful appearance, vomiting blue and white flame from his mouth

while his eyes resembled red balls of fire. She said he wore a large

helmet and that his clothing, which appeared to be very tight-fitting,

resembled white oilskin. He then caught hold of her and began tearing

her gown with claws which she was certain were of some metallic

substance. She screamed for help, and managed to get away from him and

ran towards the house. He caught her on the steps and tore her neck and

arms with his claws. She was rescued by one of her sisters, after which

her assailant fled. Eight days later, Lucy Scales and her sister were

returning home after visiting their brother, a butcher who lived in a

respectable part of Limehouse. As they passed through Green Dragon

Alley, they saw someone standing in an angle of the passage; he

approached her, wearing a large cloak and spurted a quantity of blue

flame in her face, temporarily blinding her and causing violent fits

which lastested several hours. Her brother, hearing the screams, ran to

her aid. Her sister reported that the attacker was tall, thin, of

gentlemanly appearance, wore a cloak and was carrying a lantern

similiar to the bull's eye lantern carried by policemen; he did not attack her, but walked away.

No-one was ever found. |

| In 1836, Thomas Murray, a dealer in metal, appeared at the

Thames Police Office.

He and a companion Edward Bloxham had been arrested with

400 pounds of lead in their possession. It was said to have been doubled up and beaten

together in such size and shape as to be carried ... under the clothes

of the person conveying them, suspended on a belt fastened

round the body or ... from the braces or neck. The magistrate required him to not only that he had

purchased the lead found in his possession, but also that it [had]

been bought under such circumstances as would remove the suspicion

attached to it. Murray responded that he did a deal of business in

the lead trade and that he could not speak to every piece of it.

He was convicted and fined £5, the magistrates (William Ballantine & Thomas Clarkson) later writing to the Home Office that Murray had passed

very lightly over the strong points of the case against him. |

| Lambeth Street

Police Court: from the Tower Stairs, on the River, in a line

running northward along the boundary of the city of London, to the

corner of Wentworth Street; thence eastward along the centre thereof,

and of Old Montague Street, Prince's Street, and Northampton Street, to

Cambridge Road; thence northward along the centre thereof to Old Ford

Bridge; thence to and along Old Ford Road to and including Bow; and

thence to the River Lea; thence southward along the River Lea to the

north corner of the East lndia Dock; thence westward along the centre

of East India Dock Road, and of the Commercial Road, to the corner of

Street Road; thence southward along the centre thereof, and of Cannon

Street, to Ratcliff Highway; thence westward along the centre of the

same, and of Parson's Street, to East Smithfield; thence southward to

and along the centre of Nightingale Lane to Hermitage Dock; thence

westward the boundary of the River Thames to Tower Stairs, including

the Tower of London and the liberty thereof ... |

| Thames Police Court: from the River Thames, Old Gravel Lane Stairs, in a line running northward along the centre of Old Gravel Lane, and extending to and along the centre of Cannon Street, and Cannon Street Road, to the Commercial Road; thence eastward along the centre thereof, and of the East India Dock Road, to the north of and including the East lndia Docks, to the River Thames; thence westward along the boundary of the said River to Hermitage Dock; thence northward to and along the centre of Nightingale Lane to East Smithfield; thence eastward to and along the centre of Parson's Street and of Pennington Street, to Old Gravel Lane; thence southward to and along the centre thereof to the River Thames, at Old Gravel Lane Stairs ... |

| Tower

Stairs to High Street Whitechapel, Gobe Lane, Mile-End Road, Eastern

Counties Railway, Hackney Cut, Bow Bridge, along the River Lea to the

Thames, Tower Stairs. |

| THE TIME OF DAY

AT THE THAMES POLICE COURT The advantages of early rising for the administration of justice are signally instanced and explained in the subjoined extracts from a relative to the Thames Police Court:— AS IT SHOULD BE. The Magistrates of this court have commenced business fifteen or thirty minutes past ten o'clock since the 6th instant, to the great convenience of the public. The change has effected immense good. The Magistrates have been enabled to leave the court every afternoon at five o'clock, and good and quiet order has prevailed.The people attending upon the night charges and remands are away before the persons attending on summonses arrive. There has been no quarrelling or disorder in the avenues leading to the court, and there is no prospect while the present system continues of people being detained until seven and eight o'clock in the evening, or of leaving the court wearied, exhausted, and disappointed. It may with truth and justice be averred that Early to bench and early to rise Marks a Beak popular, pleasant, and wise. The parties, however, who are interested in the dispatch of business at the Thames Police Court find that 10.15 or 10.30, though vastly preferable to 11, is not quite sufficiently early to completely suit their convenience; and they say that If the Magistrates will follow up their good intentions and commence at ten o'clock precisely every morning (the hour at which the judges commence business in Westminster Hall), they will confer another boon on the inhabitants of the district. Two additional clerks are much required. Two clerks were to tbe Thames Police Court when it was first established 60 years ago. The has since increased tenfold, and no additional clerks have been appointed. Two clerks are not sufficient for the business of tbe Court, and were it not for the assistance of the ushers and summoning officers, matters would be brought to standstill. It does not seem unreasonable to ask his Worship, the Magistrate, to turn out at the same hour in the morning with my Lord Judge. The rogues are all up and doing betimes, and justice ought to be even with them. The moralist in tbe Grammar declares that the way good manners is never too late; but it appears that a Magistrate be a little too late and nevertheless on his way to amendment. For we are further apprised that on Tuesday last week Mr. Woolrych arrived at tbe Court this morning at a few minutes after ten, heard the applications immediately and commenced the hearing of the charges at half past ten. A few minutes past ten is only a few minutes too late. It is an approximation to ten sharp; which is the desiderated hour. The Thames Police Court reporter seems happy to report that the Magistrates in their attendance there, are tending to that hour, which, when they have adopted it precisely to a minute, will be just the time of day. |

| A national, independent, gratuitous magistracy, giving their time, their learning, and their efforts to the preservation of the peace and good order of society, and the due administration of the laws throughout the country, reconciles all even to their severest exercise, inasmuch as it proves that general good, and no sinister motive or interest, can actuate those who so engage in the public service ... Can such a feeling prevail with respect to a stipendiary body? ... Will not the feeling be ... that the members of such a body are the servants of the Government, instead of the independent guardians of the public interest? [And be begged of the King] ... the gracious boon of an independent magistracy for the Metropolis. |

There were about sixty such courts around the country, five of them in London. The Westminster, Southwark and Tower Hamlets courts were set up around the same time, in the early 18th century. They dealt originally with claims under £2, but in the 1830s this was increased to £5. The Tower Hamlets court, in Whitechapel, met every Thursday, and its proceeedings were described as short and easy to the Suitors - actions taken here could not be transferred to the higher courts. Its steward from the 1770s until his death in 1822 - combined with various other legal roles - was Sir John Silvester, who had been a barrister (featuring in semi-fictional roles in the 2009-11 BBC series Garrow's Law - played by Aidan McArdle), a 'Common Pleader', a Serjeant and then Recorder (senior judge) of the City of London. The 'Prothonotary' (principal clerk) was R.W.L. Farmer, and counsel Philip Keys - both of whom also held office elsewhere. Because of the poverty and population density of the East End, this was by far the busiest of these courts, conducting up to half of all the business across London. James Grant, in Sketches in London (1838), comments The Tower Hamlets’ Court of Requests affords an apt illustration of the well-known adage: 'Most work, least pay'. The principal clerks, though they are much harder worked than the clerks of any of the other Courts of Requests in London, have the smallest pay of any. They have only £300 each, without one sixpence in the shape of fees. (Clerks in some other similar courts did receive fees - regimes varied widely.)

The Tower Hamlets Court of Requests had no less than 240 Commissioners,

chosen annually from ratepayers by the parishes of its area; typically, twenty or so would sit at

each session. They originally had the power to imprison for up to 40

days, under the 1749 Tower Hamlets Court of Requests Act (23 Geo 2 c20) but this was removed by the general 1823 Gaols &c (England) Act (4 Geo 4 c64), and was not restored by the next local act, the 1832 Tower Hamlets Court of Requests Act (2 Will 4 c65): this was confirmed by a King's Bench case of 1833, R v. the Governor of the Middlesex

House of Correction (1833) 3 Law J (NS) MC 124 / 2 Neville & Manning 138, which can also be read here (p170). The City of London and County of Middlesex magistrates

accordingly denied access to the debtors' prisons under their control.

This is probably the reason why (despite upping the limit for claims) in the

1830s the court's business roughly halved: traders became more cautious

in giving credit, and less inclined to prosecute for debts, knowing that their

chances of successful recovery were reduced. Vol.1 of the Statistical Society of London (1839) gave these figures:

| debts not exceeding £2 |

debts not exceeding £5 |

|

| 1829 |

29,961 |

|

| 1830 |

28,375 |

|

| 1831 |

27,388 |

|

| 1833 |

15,744 |

2,816 |

| 1834 |

13,688 |

2,533 |

| 1835 |

11,744 |

2,097 |

The Court was in Osborn(e) Street, behind what is now the Whitechapel Art Gallery [junction with Whitechapel Road above right around 1890 - long after the court had gone]. Reforms for these small courts were proposed throughout the period. In the event, they were all abolished by the 1846 Small Debts Recovery Act, later known as the County Courts Act, which established a system of national courts to deal with civil matters (amended 1888 and 1934 and subsequently); its premises remained in Osborn Street for the following decade. They dealt with debts up to £50, and tenements worth up to £50 a year.

| Edmonds & others v. Challis & others (Court of Common Pleas 1848 & 1849) Prior to the Act, and the new courts it established, Sheriffs distraining debtor's goods took out a bond for replevin, with a charge for the 'obligor' to appear at the local Sheriff's court or office (in this case, at Red Lion Square) to 'prosecute his Suit with Effect'; but in a case where the Sheriff was sued for proceeding in this way, after lengthy technical argument Coltman J. held that this was no longer insufficient: it must go through the county court. |

| Pollett v Chesterton - custody of a prisoner committed by a County Court Judge (Queen's Bench 1849) In 1848 Pollett, a 'respectable' clerk on the South Western Railway, was sued by Ridlington at Whitechapel County Court for £1 19s, on a purely civil matter, with no question of fraud, the point at issue being whether Pollett was entitled to deduct a attorney's fee from money he had collected for Ridlington. In less than three minutes the court found for Ridlington, with an order that the debt should be paid by instalments. Three weeks later Pollett was carried off to Coldbath Fields Prison, where the Governor, George Lavall Chesterton (a zealous proponent of reform who claimed in his autobiography to have transformed Coldbath Fields from one of the worst speciemens of corruption and misrule into an establishment distinguished for industry, order and impressive discipline) allegedly greeted him with the words You are sent here for correction, and correction you shall have. He was subjected to the full prison regime: uniform, diet, hair and whiskers shaved off, marked with a number and set to picking oakum. There were many letters and protests at the time against the application of the new punitive regime to the middle classes, as the Home Office sought unwisely to lump together small claims defendants with fraudulent bankrupts and insolvents as 'penal debtors'. Baillie Cochane raised the case in the House of Commons, describing it as a case of great oppression involving unjustified stigma of his character. Pollett sued (in forma pauperis - without liability for fees) the governor for trespass and illegal imprisonment, saying he had been degraded, and was a most injured man... He was most reuptably connected and ... had lost his character, and should have some difficulty to obtain another situation. The basis of his action was that no judgement summons had been issued for his imprisonment, as required by s98 of the County Court Act; that the Governor refused to provide a copy of the warrant; and likewise the Home Secretary, who claimed he had no control over the matter. It therefore became a consitutional question. Wightman J instructed the jury to find for Pollett, since all that had been done must be taken as illegal, and there was no issue of justification. All the governor could ask was that under the circumstances the damages should be mitigated, on the ground that he had acted as a public officer in the discharge of his duty. The County Court had power to commit to the House of Correction under the statute, but nothing was said about how the prisoners were to be treated. The judge later instructed the jury to assess the various damages separately, which after long deliberation they did: £5 for imprisonment; £10 for searching and shaving; £10 for improperly treating Pollett as a misdemeanant. |

| Dews v Riley, Court of Common Pleas (1851) 11 C.B. 434 Dews was sued at Whitechapel County Court by one Davis in July 1850 for £3 17s and 14s 4d costs, an an order was made that he should pay by monthly instalments of 5s. He failed to do so, and a judgement summons for 10 October was issued under s98 of the Act. He failed to appear and an order, duly recorded in the court book, was made On the 17th October instant, or thirty days' imprisonment for not attending. By 17th he had failed to pay, and a further order was made for payment of £5 2s 8d (adding in the additional costs of this summons) or committal for 30 days to Whitecross Street; he was arrested on a warrant bearing the seal of the county court, signed by Riley, the clerk, and detained. He sued for trespass and false imprisonment. The issue here was that, although the judge in his evidence and a private memorandum stated that his intention was to make a postponed order (issued on 10 October for commitment forthwith on the understanding that it would not be enforced until the following week), he had no power to do so, but only to make a peremptory order for immediate committal. The court was bound by the evidence of the recorded entry, albeit incorrectly made. Riley pleased not guilty, by statute: in issuing the warrant he was simply acting as required by s102 of the Act, even though the order turned out to be bad. The court (whose judgement was delivered by Sir John Jervis CJ) agreed: he was a mere ministerial officer, and could not be expected to review the decision of his superior, the judge. At the suggestion of the court, Dews 'nonsuited' (terminated the action without prejudice or costs). |

| Lavey v The Queen ( 20 July 1851) Ann Lavey, widow & executrix of Hyman Lavey, was charged with perjury, having stated on oath that she has not been tried at Central Criminal Court for any offence (which in fact she had in 1843, for feloniously uttering a forged endorsement to a bill of exchange, defrauding Adolphus Brand and another) nor had ever been held in custody at the Thames Police Court (which again she had in the same year, having obtained £1 5s by means of a forged note, defrauding Thomas Yates). She claimed (clutching at straws) defects in the indictment: that the county court was not properly specified; that it had no jurisdiction and that the judge had no authority to hear the case, or to administer the oath to her as a witness in her own behalf (rather than as plaintiff on behalf of her deceased husband); and that it did not state that the oath was taken on the Holy Gospel of God or in any other manner. Parke B (Baron of the Exchequer Court) rejected these claims: he held after verdict upon writ of error, first, that the court was sufficiently designated as a court held under stat. 9 10 Vict c 95; and, secondly, that although there was no express averment that the oath was administered in a judicial proceeding over which the court had jurisdiction, that averment was, by necessary intendment, involved in the allegation that the judge had sufficient authority to administer the said oath. In other words, the court, the judge, and the oath were all in order. |

| Kidnapping a Tailor (1851) — Jamieson v. Ramsay

was an action of tort. Jamieson was a retired tailor owned 'Labour's

Retreat', a villa on the banks of the Thames. Ramsay, an old

'man-of-war's man' owned various properties in Whitechapel but preferred to live afloat, and equipped a yacht of six guns, the Tom Bowling,

in which he lived. On Easter Mondays Jamieson held a festive

anniversary, letting off cannon to mark the day of his wife's death. On

the last anniversary Tom Bowling

was cruising off 'Labour's Retreat', and when her crew smelt the

powder, all hands were piped for action, and they returned fire. Firing on both sides continued until the landsmen put stones

in their guns and riddled Tom Bowling's

duck and streaming bunting. Her boatswain then seriously

damaged the tailor's chimney-stack. Captain Ramsay landed his

crew, to demand satisfaction for the insult offered to his flag, and

having thrashed the tailor's friends, challenged Jamieson, politely

offering him swords or pistols. Thinking it safer to faint than to

fight, Jamieson swooned away, upon which Ramsay ordered him to be taken

prisoner; when he recovered his senses Jamieson found himself under

hatches of the yacht, where he was kept the whole night, bewailing the

misfortune of being kidnapped by pirates, as he termed his captors. In

the morning he was brought before Ramsey and subjected to a

court-martial, for insulting the British flag, and being found guilty

was sentenced to the yard-arm. He begged for mercy, however, and, as a

last resource, offered up prayers. The sentence was then commuted to

the infliction of an operation performed on sailors when first crossing

the line. In that state he was transported to Herne Bay, forty miles

from home, without a farthing in his pocket. The judge awarded Jamieson

£5 damages, without costs. |

| Breach of Promise (1856) — An

action of trover: The plaintiff, Mr

McGregor, was a schoolmaster, and Mrs Page, the defendant, a widow

carrying on a small grocery business. McGregor said: —Ye dinna remember whan I first got acquainted wi' Mistress Page, but, waes me, I do. Weel, your Honour, last Christmas I left Perth for this modern Babylon, and have endeavoured to establish a school, wi' sma' success, being a stranger. I was never a disciple of Thales, the Milesian, upon the subject of matreemony. When the mither of that learned philosopher asked if he wad na marry, adding that a gude wife was the greatest blessing a man could enjoy, he shook his head, and did not make her any answer; but upon pressin' the feelosopher, he replied, he was too young, and when he got old he was very deeficult on the article of marriage. I really thocht that I had never seen a better-faured, or a more gallant-looking lass, and it was'na very lang until I drew up — and tho' she didna gie me any great encouragement at first, yet in a week or twa after the ice was fairly broken, she became remarkably ceevil, and gied me her oxter sae often, that the shoemaker was no loser by it. I represent to her how useful I could be in her storehouse after school hours, by keepin her buiks, for puir ignorant cratur, to see them one wad think she dipped blue bottle flies in the ink, and let them loose on her accounts. When I put the important question, she was see mim, and left it like to myself. 'O, Mistress Page', says I, 'I am owre happy now — oh, hand my head.' This gift, 'O Joy is like to be my dead'. 'I hope not, mate', says she, 'I wad rather hae ye to live than dee for me.' That same nicht I tak her to the goldsmiths in Cornhill, and clap on her finger the golden hoop, and here I wad observe that the laws of matreemony in Great Britain are determined by longitude and latitude — for had the leddy done one half the other side of the border, in our courtship, she wad hae been married to me for a dead certainty; and I wad further observe, that at the Act of Union, it was by grievous error the Lords Commissioners did not asseemilate the English to the Scotch marriage laws.— fter she had got the ring she grew cold towards me, complained of my snuff-taking, and of the tint o' my hair. She now laughs at me, and refuses to gie me back the ring. I now beseech the court to order its return. Mrs. Page said she had offered to pay for the ring, and the reason she could not return it was that the plaintiff had placed it on the fourth finger of the right hand so tight that she could not get it off. It was also a gift. The Judge said, it being a gift, he could make no order. — Verdict for the defendant. |

A new court was built in 1857 in [Great] Prescot

Street - left in 1938, and further described here.

A new court was built in 1857 in [Great] Prescot

Street - left in 1938, and further described here.  Jack Hicks [right], landlord of the King's Arms Tavern in

Whitechapel Road, and a noted puglilst [boxer] brought two actions in

this court. The first, in 1862 (reported in the stage magazine The Era as The Fancy in the Dark), was against Lawrence Levy, proprietor of the Garrick Theatre,

Goodman's Fields, who was apparently more interested in the sale of

alcohol than in organising performances. In the following year, In Hicks v. Windham, he

sought to

recover £29 8s. from his former patron the Hon. Mr. Windham, of

Felbrigg Hall, Norfolk, for various colours or silk handkerchiefs

supplied after his victory in a match near Gravesend (a venue that had

become less popular as the railways enabled tourists to go further

afield). Hick's solicitor

was B.J. Abbott of Mark Street [later St Mark's Street], but Windham did not appear, and was

said to be on a yachting excursion at Weymouth. The judge said there

was no proof that he had received the summons, although it had been

served on his solicitors, so the case was adjourned.

Jack Hicks [right], landlord of the King's Arms Tavern in

Whitechapel Road, and a noted puglilst [boxer] brought two actions in

this court. The first, in 1862 (reported in the stage magazine The Era as The Fancy in the Dark), was against Lawrence Levy, proprietor of the Garrick Theatre,

Goodman's Fields, who was apparently more interested in the sale of

alcohol than in organising performances. In the following year, In Hicks v. Windham, he

sought to

recover £29 8s. from his former patron the Hon. Mr. Windham, of

Felbrigg Hall, Norfolk, for various colours or silk handkerchiefs

supplied after his victory in a match near Gravesend (a venue that had

become less popular as the railways enabled tourists to go further

afield). Hick's solicitor

was B.J. Abbott of Mark Street [later St Mark's Street], but Windham did not appear, and was

said to be on a yachting excursion at Weymouth. The judge said there

was no proof that he had received the summons, although it had been

served on his solicitors, so the case was adjourned.  In 1871, under the County Courts Admiralty Jurisdiction Act 1868,

Whitchapel County Court took over maritime cases from various other districts, including

Rochford, Brentwood, Romford, Dartford, Gravesend, Greenwich, Woolwich

and the City of London, presumably because it had acquired expertise in

this area because of its location. An 1899 Order in Council continued this jurisdiction, but by the County Courts (Mayor's and City of London Court) Admiralty and Jurisdiction Order of 1932 it was transferred to the Mayor's and City of London Court [right].

In 1871, under the County Courts Admiralty Jurisdiction Act 1868,

Whitchapel County Court took over maritime cases from various other districts, including

Rochford, Brentwood, Romford, Dartford, Gravesend, Greenwich, Woolwich

and the City of London, presumably because it had acquired expertise in

this area because of its location. An 1899 Order in Council continued this jurisdiction, but by the County Courts (Mayor's and City of London Court) Admiralty and Jurisdiction Order of 1932 it was transferred to the Mayor's and City of London Court [right].  His successor, at Whitechapel but now also at Shoreditch (Leonard Street EC2 - left in 1919) rather than Bloomsbury, from 1911-34 was Albert Rowland Cluer,

who was of a similar ilk - both as a controversialist and a 'judicial

wit': some of his many reported sayings and cases are noted here.

The area served by both these courts had become overwhelmingly Jewish - one jury was said to have been compsed entirely of Cohens - and (as a classicist who published translations of Livy and Xenophon)

he studied Hebrew in order to understand some of his clients.

Its bailiff at this time rejoiced in the name of Ebenezer Crottick.

His successor, at Whitechapel but now also at Shoreditch (Leonard Street EC2 - left in 1919) rather than Bloomsbury, from 1911-34 was Albert Rowland Cluer,

who was of a similar ilk - both as a controversialist and a 'judicial

wit': some of his many reported sayings and cases are noted here.

The area served by both these courts had become overwhelmingly Jewish - one jury was said to have been compsed entirely of Cohens - and (as a classicist who published translations of Livy and Xenophon)

he studied Hebrew in order to understand some of his clients.

Its bailiff at this time rejoiced in the name of Ebenezer Crottick.

The Whitechapel Court closed in 1944 and was 'consolidated' with

Shoreditch, and was known as 'Shoreditch County Court'.

This in turn was joined to the Clerkenwell Court in 2006, as

'Clerkenwell and Shoreditch County Court', with a new court in Gee

Street [first right].

Other business had been transferred to Bow County Court [not to be

confused with Thames Magistrates' Court in Bow Road], now housed in Romford Road [second right - what

a contrast with the handsome Prescott Street building!] - and

dealing with adoption, children, divorce, domestic violence, money

claims and repossession cases.

The Whitechapel Court closed in 1944 and was 'consolidated' with

Shoreditch, and was known as 'Shoreditch County Court'.

This in turn was joined to the Clerkenwell Court in 2006, as

'Clerkenwell and Shoreditch County Court', with a new court in Gee

Street [first right].

Other business had been transferred to Bow County Court [not to be

confused with Thames Magistrates' Court in Bow Road], now housed in Romford Road [second right - what

a contrast with the handsome Prescott Street building!] - and

dealing with adoption, children, divorce, domestic violence, money

claims and repossession cases.«« History | «« Goodman's Fields 2 | »» Stipendiary Magistrates | »» County Court judges | »» F.O. Langley | »» Judge Bacon | »» Judge Cluer