Statistical Society of London Report (from its Quarterly Journal, August 1848)

This report

was compiled using the new science of statistics, correlating a

mass of data collected in 1845 in part of the parish. The original can

be seen here. What follows is the text and most of the tables, with comments interleaved. Emboldening of text is editorial.

Report

to the Council of The Statistical Society of London from a Committee of

its Fellows appointed to make an Investigation

into the State of the

Poorer Classes in St. George's in the East, with the sum of £25 given

for this purpose by Henry Hallam, Esq., F.R.S., aided by a Donation of

£10 from R.A. Slaney, Esq., M.P., and further sums from the General

Resources of the Society.

[Read before the Statistical Society of London, 17th April and 15th May, 1848]

St George's in the East was selected for this inquiry as a district

comprising a considerable population of the labouring classes,

resembling in condition the people of many surrounding localities, and

offering, in fact, an example of the average condition of the poorer classes of the metropolis.

The general mass of the labouring population in urban localities, where

they are subject to influences over which they have but a partial

control, being now avowedly an object of public policy as well as

philanthropic solicitude, the Committee, with the advice of the

gentleman whose liberality had given it being, determined to make a

complete and detailed examination, and a careful analytical statement

of the condition of such a body of the poorer labouring classes of the

metropolis, as their means would permit them to embrace within the

limits of their inquiry, rather than devote those means to exhibiting

the condition of any one of those lowest sinks of barbarism and vice,

which sanitary and other reports have recently placed with such painful

truth before the public, Investigation must not stop until these are

removed, for they are but the local accumulation of general evils,

which can never be completely dissipated until great changes have been

accomplished in the whole frame of society. But since their population

is, to some extent, the drainage from the grades next above them, we

should rather hope to find a cure by cutting off the supply of

degradation than by attempting to reform and elevate it in the lowest

depths to which it can sink.

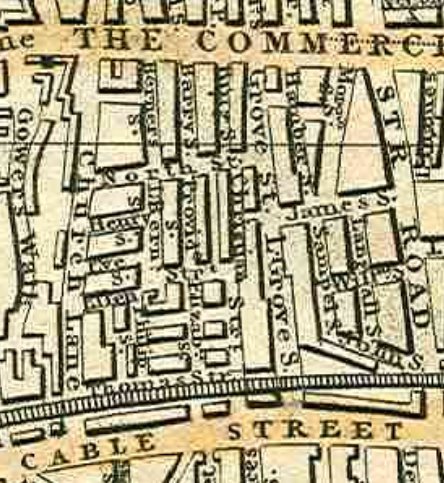

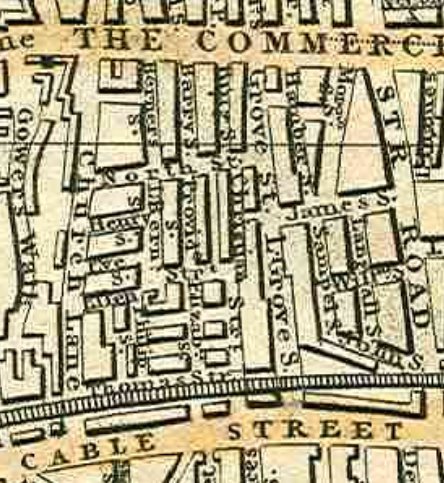

The St. Mary's district of St George's in the East was accordingly

selected for the elaborate analysis which it was determined to make;

and the portion concerning which it was ultimately found practicable to

obtain every varied item of information, was the great block of

habitations included between White Horse Lane, which is the

commencement of the Commercial Road, on the north, and Cable Street and

the New Road on the south; and between the New Road on the east and

Church Lane on the west. This is, in fact, the whole of St Mary's

district north of Cable Street; and it is one of those composed of

dingy streets, of houses of small dimensions and moderate elevation,

very closely packed in ill-ventilated streets and courts, such as are

commonly inhabited by the working classes of the east end; and indeed,

it may be said, of all parts of London beyond the limits of that

congested band round its centre, where overcrowding is carried to the

greatest excess.

The St. Mary's district of St George's in the East was accordingly

selected for the elaborate analysis which it was determined to make;

and the portion concerning which it was ultimately found practicable to

obtain every varied item of information, was the great block of

habitations included between White Horse Lane, which is the

commencement of the Commercial Road, on the north, and Cable Street and

the New Road on the south; and between the New Road on the east and

Church Lane on the west. This is, in fact, the whole of St Mary's

district north of Cable Street; and it is one of those composed of

dingy streets, of houses of small dimensions and moderate elevation,

very closely packed in ill-ventilated streets and courts, such as are

commonly inhabited by the working classes of the east end; and indeed,

it may be said, of all parts of London beyond the limits of that

congested band round its centre, where overcrowding is carried to the

greatest excess.

The civil

district of St George-in-the-East had three sub-districts, St Mary's,

St John's and St Paul's. The area surveyed was shown on

this 1844 map: before Commercial Road was developed it was known as

White Horse Lane [not to be confused with the present-day White Horse

Lane further east], Church Lane was not known as Backchurch Lane until

the 1860s, and Cable Street east of Cannon Street Road was still called

New Road.

The period occupied in the inquiry was chiefly the summer half of the

year 1845, and the abstract was made in the course of the following

year. Annexed [not included here] is the form of a table in which the particulars relating

to the several families in each house were carefully registered, after

they had been collected in note books with marginal indications

corresponding with the headings of this table. A complete

re-arrangement of the materials was then made under the head of each

occupation. From these second abstracts the following tables have been

compiled.

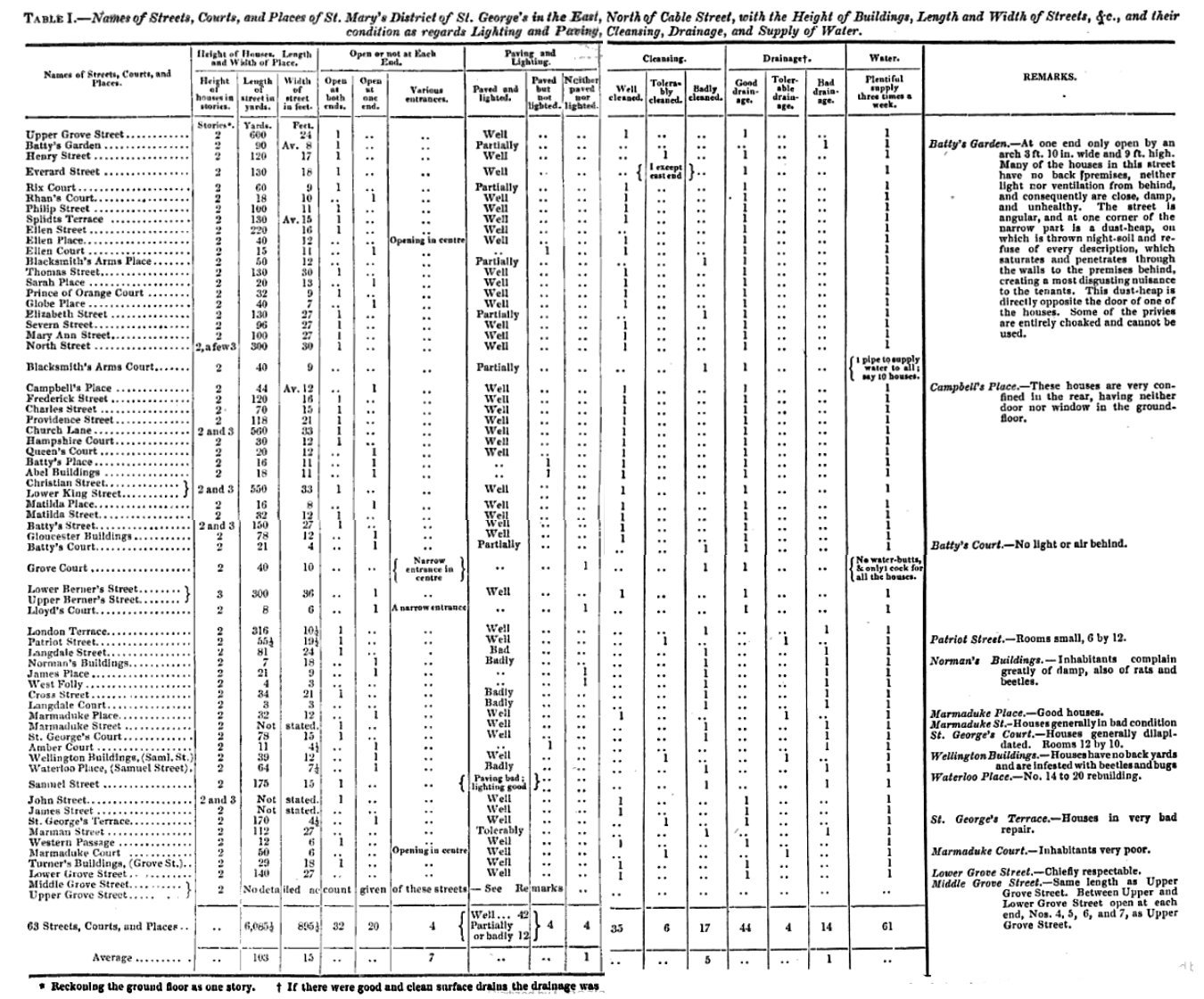

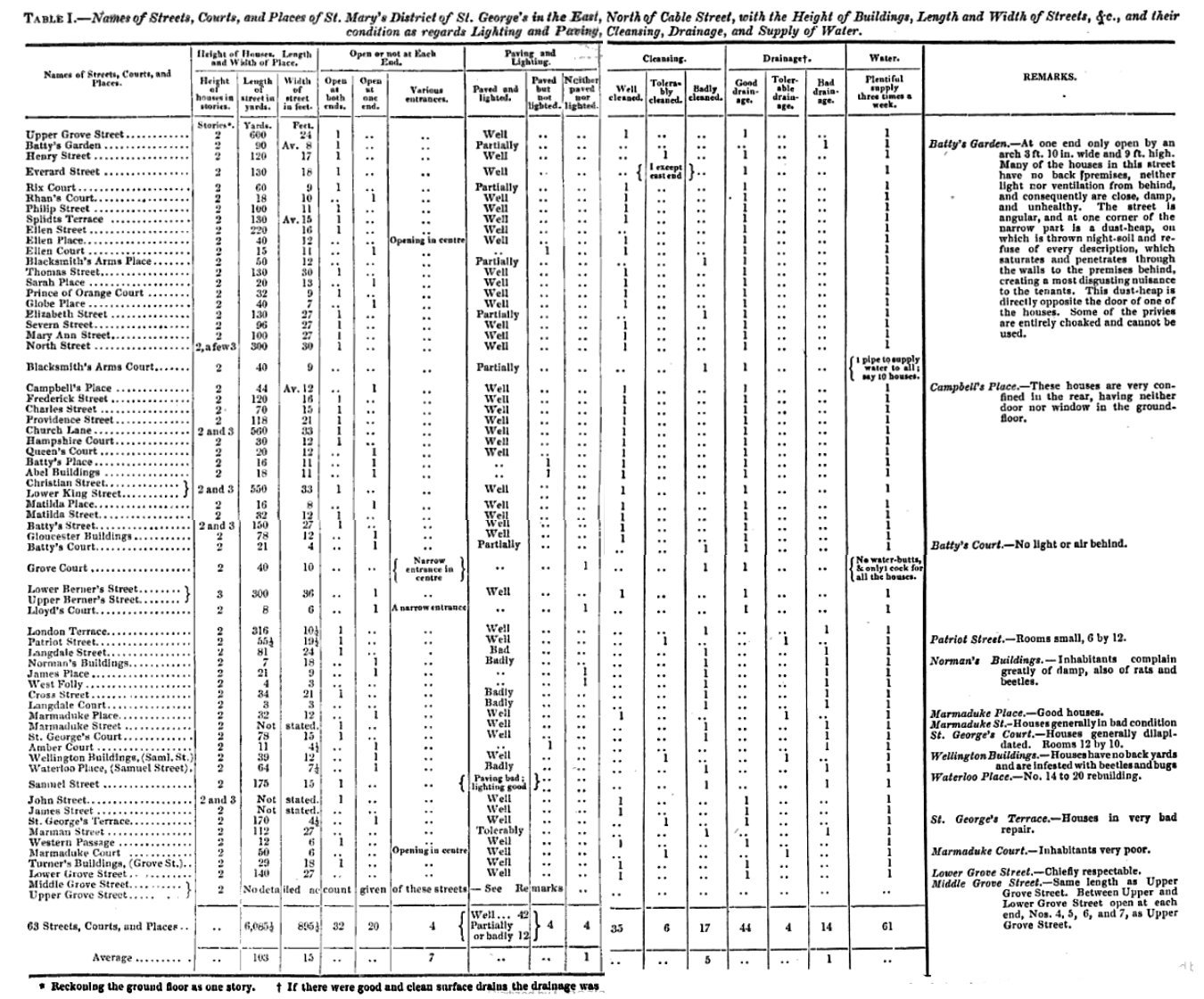

The annexed preliminary table shows the condition of all the streets in

this region, with the exception of Upper and Middle Grove Streets,

which are almost wholly occupied by persons in a condition of life

somewhat above that of the poor labourers who surround them.

See here

for Upper, Middle & Lower Grove Street, later the site of St John

the Evangelist-in-the-East Church; note the exclusion of part of it as

being 'chiefly respectable'. The extent of paving and lighting is

higher than might be expected. Many of the courts and yards were to

disappear by the turn of the century.

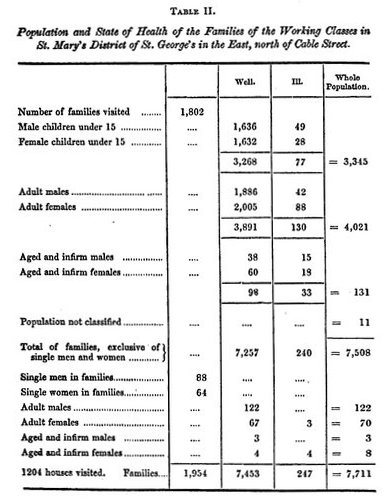

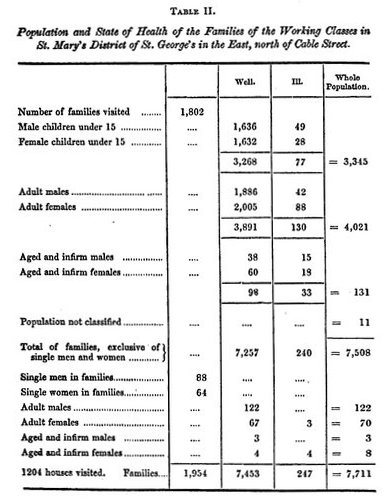

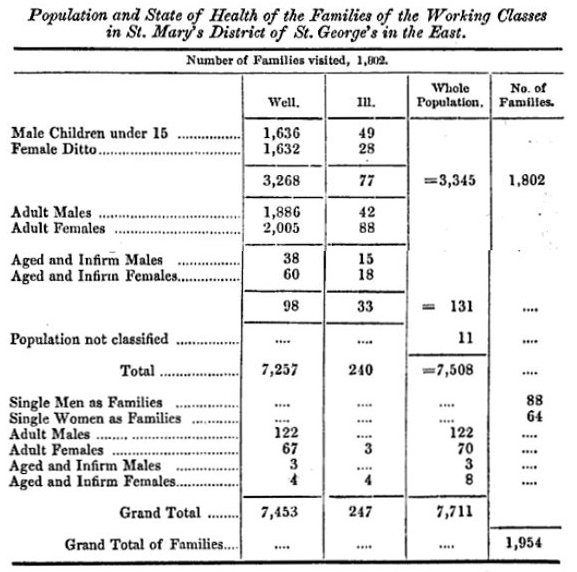

Illness, in the meaning of the following table (II), is such as produces

confinement to the house, and incapacity for labour or exertion. The

proportion of such illness is small; and the appearance of the

children, even, is very healthy, wherever there is a sufficiency of

food; for they are early sent, as much as possible, out of the confined

rooms of their parents, though sometimes into little, filthy, smoky,

dame schools, by no means preferable; except that they have to pass

through the streets to arrive at them. Others of these schools,

however, are clean and fairly ventilated, and kept by persons with

habits of order and propriety.

Illness, in the meaning of the following table (II), is such as produces

confinement to the house, and incapacity for labour or exertion. The

proportion of such illness is small; and the appearance of the

children, even, is very healthy, wherever there is a sufficiency of

food; for they are early sent, as much as possible, out of the confined

rooms of their parents, though sometimes into little, filthy, smoky,

dame schools, by no means preferable; except that they have to pass

through the streets to arrive at them. Others of these schools,

however, are clean and fairly ventilated, and kept by persons with

habits of order and propriety.

Health is further considered below.

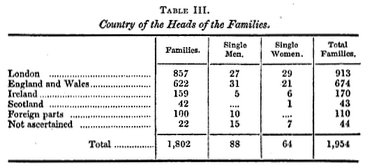

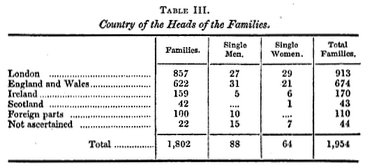

The excess of foreigners, indicated by this table (III), is partly

attributable to some foreign sailors having their homes here, but

chiefly to the sugar bakers, being nearly all Germans; and to their

credit it ought to be added, that they are a cleanly, orderly, and well

conducted body of men, chiefly worshippers at the German chapel in the

neighbourhood.

The excess of foreigners, indicated by this table (III), is partly

attributable to some foreign sailors having their homes here, but

chiefly to the sugar bakers, being nearly all Germans; and to their

credit it ought to be added, that they are a cleanly, orderly, and well

conducted body of men, chiefly worshippers at the German chapel in the

neighbourhood.

Irish immigration continued through the coming decades, concentrated in particular streets. See here for more about sugar baking, and here for

the German churches. The sugar-bakers were from Christian regions, but

other German settlers were Jewish - though the days of this as a

Jewish-majority area were several decades away.

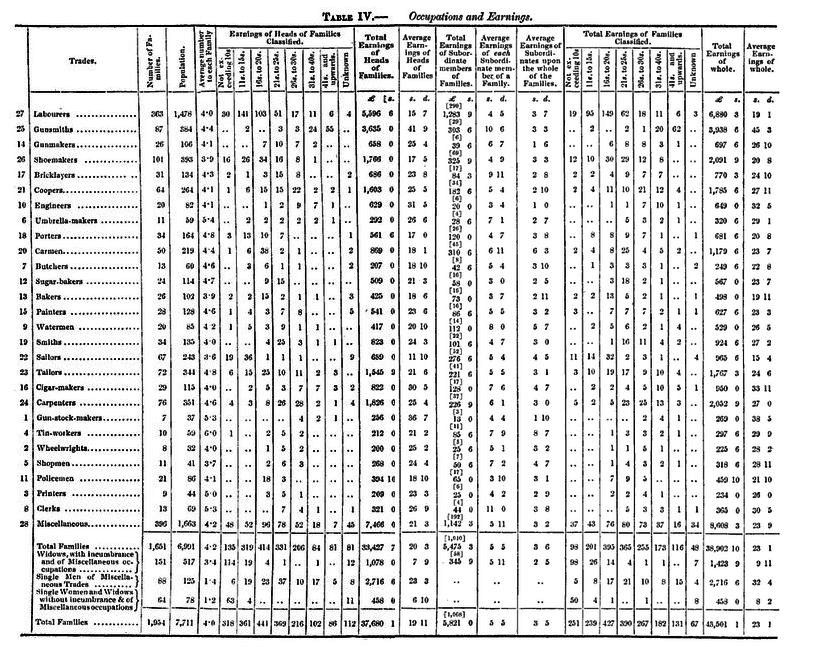

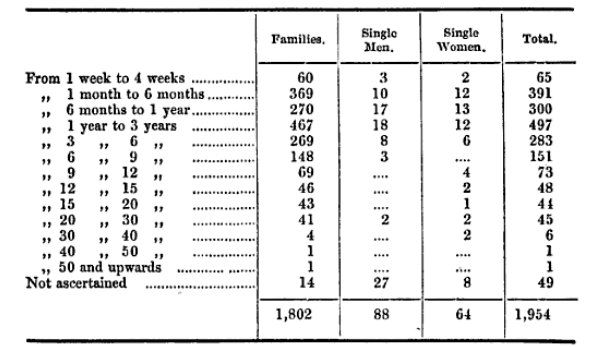

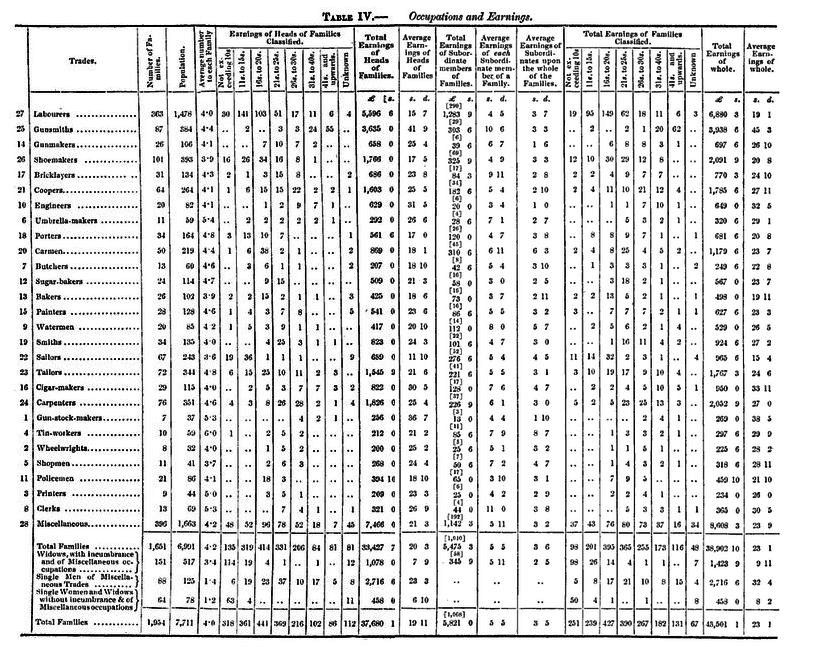

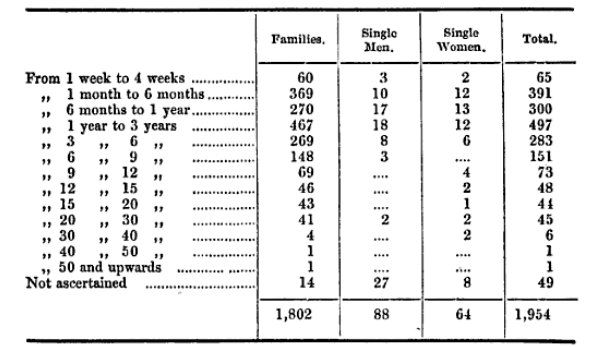

The total population–men, women, and children–included in the scope of

the present inquiry is here seen to be 7,711, comprised in 1,204

houses, and 1,954 families; reckoning as a separate family every one

whose earnings were not thrown into some common stock, for boarding and

lodging. 125 single men included in the inquiry, are thus reckoned to

form 88 families; because some of them lodge together; and 78 single

women and widows without incumbrance, make in like manner, 64 families,

an excess of gregariousness on the part of the men which is worthy of

observation.

Is it really noteworthy that single men (especially labourers) were more likely to

share accommodation than single women? See here for details about common lodging houses - mostly for men, but some for women, and a few mixed.

The economical condition of single persons of both sexes being

altogether different from that of the great mass of the population,

they are kept under separate heads in the following abstract, as also

are 151 widows, with incumbrance, the total number in whose families

amounts to 577, or nearly 3½ in each family, while the general average

of the district is 4. The remaining 1,651 families, including 6,991

individuals, or 4¼ individuals to each, are classified, as far as

possible, according to the occupation of the head of each; being that

circumstance which brings in its train the most numerous and most

potent of the influences which affect the relative condition of all.

Every occupation which had any considerable number of the heads of

families engaged in it, is, in fact, separately specified in the

following tables, and they are 27 in number; leaving a surplus of 396

families, including 1,663 individuals, still unclassed, under the head

of miscellaneous. These, however, are all brought together in a

separate sheet, similar to those in which the whole of the particulars

concerning each of the other groups is abstracted. Annexed is a list of

these groups, with the numbers in each, from which it will appear that

the number of mere "labourers" (in great part about the docks) is alone

nearly equal to all the "miscellaneous"; while of shoemakers there are

101, gunsmiths 87, carpenters 76, tailors 72, sailors 67, coopers 64,

carmen 50, &c. This list is followed by a classification of the

"miscellaneous" under the heads of their several occupations.

[Table V - Classification of the 396 "Miscellaneous" heads of families:]

Agents (3), Actor, Accountant, Artists (2), Box-makers (2), Basket &

Brush-makers (6), Boiler-makers (4), Bedstead-makers (3), Block and

Last-makers (3), Brass-workers (2), Brass polisher, Brass-founder,

Brewers (4), Bell-founder (1), Boat-builder, Bookbinders (3), Builder,

Broker, Brass-finisher, Bell-hanger, Boot-blocker, Bookseller,

Chimney-sweepers (2), Coal-whippers or porters (9), Coachmen (2),

Cabmen (2), Coppersmiths (2), Coachmakers (3), Costermongers (13),

Cabinet-makers (!0), Cellarmen (6), Corn-porters (2), Cork-cutters

(12), Custom-house-officers (7), Coach-trimmer, Confectioners (5),

Comb-makers (2), Cap-maker, Coach-plater, Carvers and gilders (7),

Case-maker, Chair-maker, Corn-dealers (3), Chemists (2),

Coffee-roasters (2), Chair-bottomer, Chandler's-shop, Colour-maker,

Cane-worker, Captains (3), Draymen (4), Dyers (3), Drover,

Dock-constable, Dealers (2), Draper, Dairyman, Engravers (2), Excisemen

(2), Excise-officer, Fishmongers (6), Foremen (4), Firemen (3),

Furriers (2), French-polishers (2), Founder, Gas-workers (2), Grocers

(6), General-dealers (5), Gas-stoker, Glass-cutters (2), Gate-keeper,

Ginger-beer-seller, Hatters (7), Hair-dressers (2), Hawkers (5), House

of ill-fame, In East India-house, In Docks (2), In Post-Office (4), In

Tower, Jewellers (4), Japanners (2), Ironmonger, Interpreter,

Lamplighter, Lucifer-maker, Milkmen (6), Mathematical-instrument-makers

(4), Masons (3), Maltster, Millwright, Millman, Messengers (4),

Marine-store, Oilman, Ostlers (5), Old-clothesman, Omnibus-driver,

Opticians (2), Potmaker, Plumbers (4), Public singer, Pencil-maker,

Plasterers (6), Pewterer, Poulterers (2), Paper-maker, Polisher,

Postman, Pensioners (3), Picture-frame-makers (2), Paper-hanger,

Paviour, Publican, Pew-opener, Packers (2), Riggers (6), Rope-maker,

Rule-maker, Satin-dresser, Ship-carpenter, Sawyers (10), Soldiers (2),

Soap-makers (2), Scale-maker, Sail-makers (4), Spiceman, Salesman,

Seller of trimming, Ship storesman, Servant, Surveyor, Turners

(4), Toy-makers (2), Travellers (2), Tanner, Trimmer, Timber-seller,

Tide-waiter, Vat-makers (2), Weavers (2), Watchmen (6), Watchmakers

(5), Warehousemen (5), Wire-workers (2), Waiter, Trades not given (26)

- total 396

These

lists make interesting reading. Some of the 'miscellaneous' occupations

might seem to belong within one of the categories of the main list, but

they are mainly distinctive trades, some of them highly-skilled, plus a

scattering of 'professions'. The gun trade was well-established in the

area, due to its proximity to the Proof House;

shoemaking and tailoring, with their related trades, were to remain

significant as Jewish immigration increased. There was a small gasworks

in the area. Notice the 'pew-opener' (which also features in the list

of 'widows with incumbrances') - paid a small wage, plus tips, for

ushering the gentry to their rented seats in church.

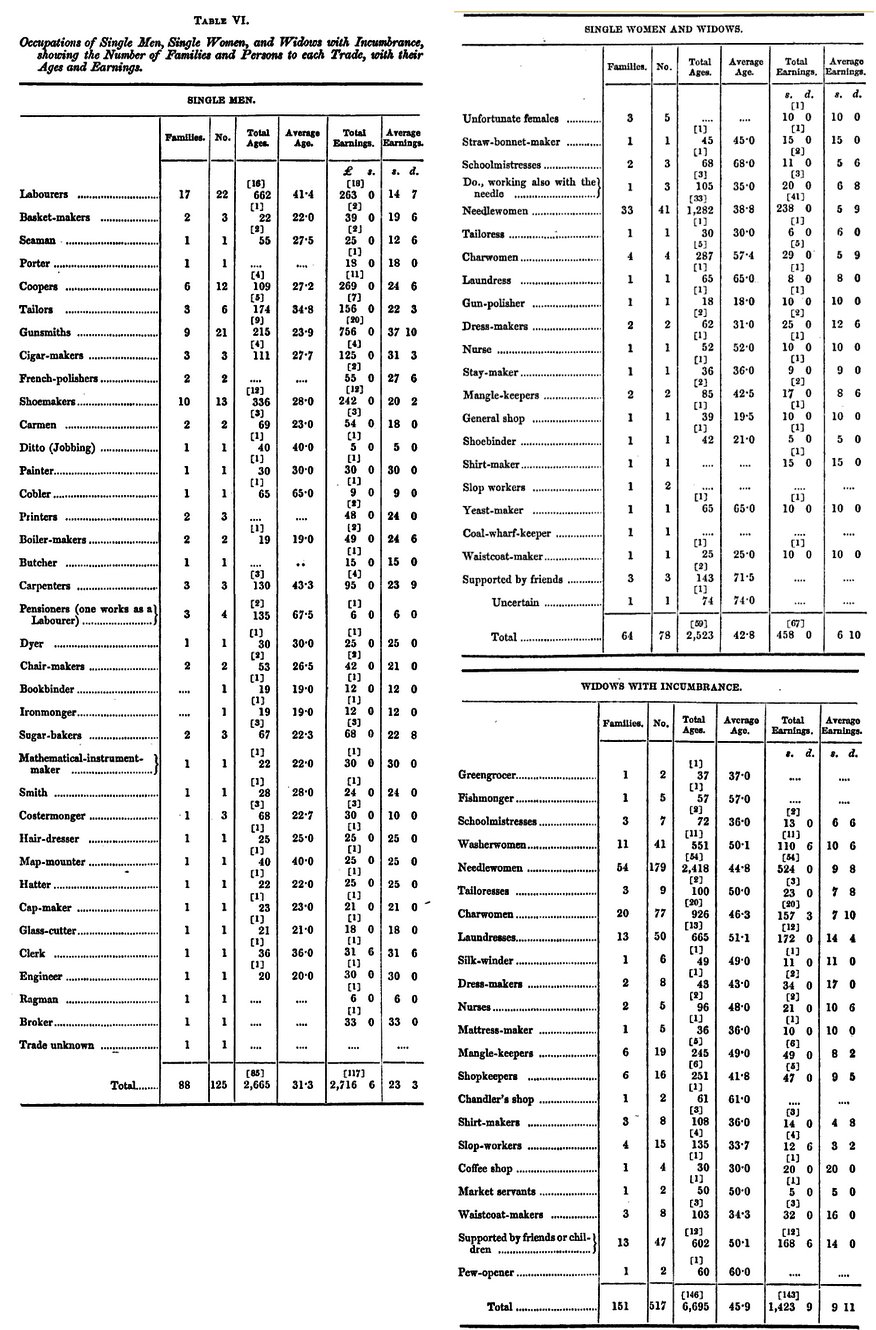

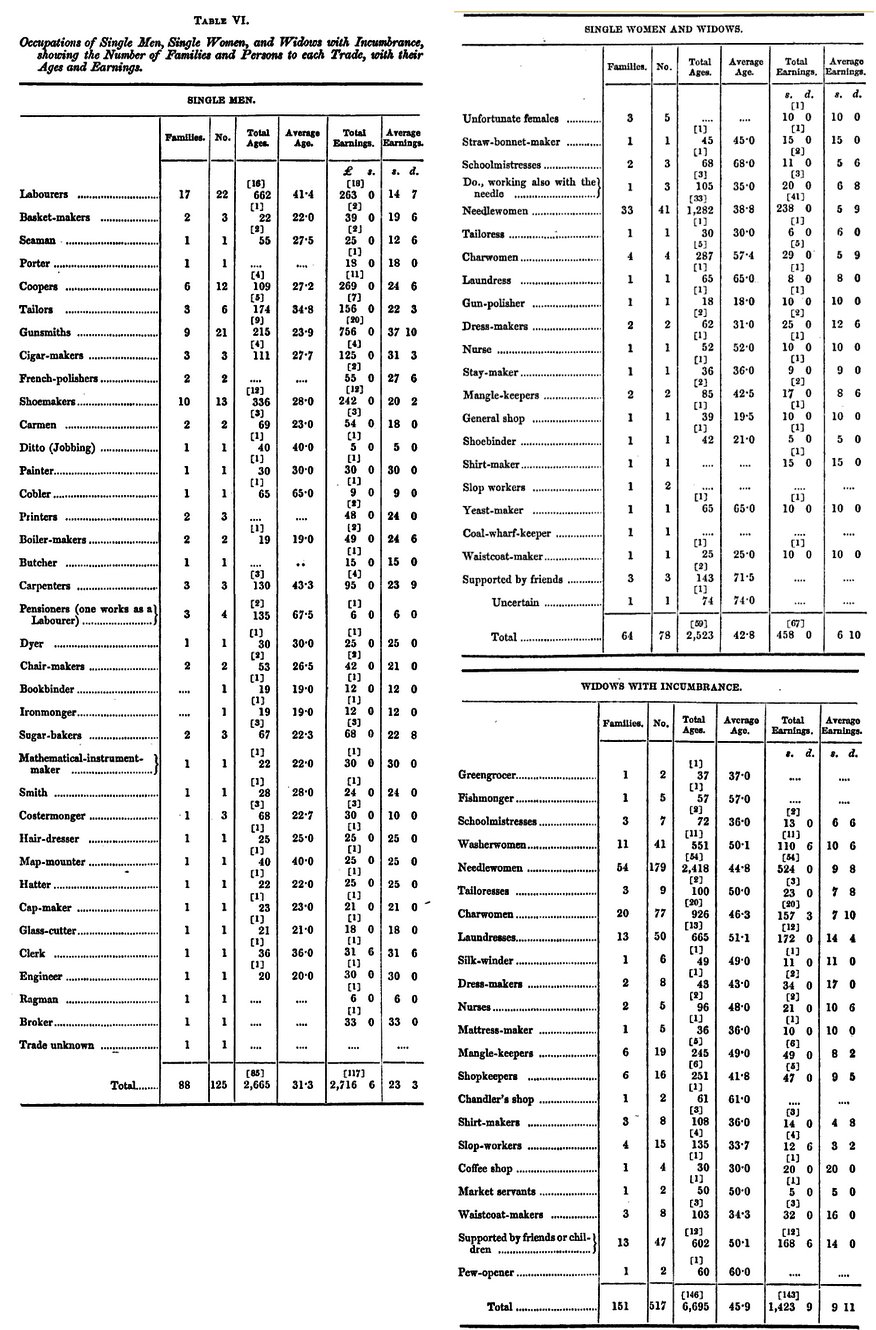

From the following (Table VI.), which shows the occupations, earnings,

and ages of the single men, widows with incumbrance, and single women,

it will be seen that the former are chiefly very young men, especially

those in the trades, earning good wages; while in the two latter

classes we find much greater diversity of age, with very limited means

derived from the narrow range of employments available for female

hands, especially if unaccompanied by a vigorous frame and habits of

bodily exertion. The extent of such employments, as compared with the

number of struggling competitors for them, being always limited, their

remuneration is always very low. The relative superiority of men's

earnings over those of the women, and even over those of the women and

children combined, in the metropolis, as compared with most of the

manufacturing districts, is thus very conspicuously shown. The

"distressed needlewomen" are undoubtedly a numerous class, in most

parts, and especially in this part of the metropolis; unprotected

women, in this district alone, being no fewer than 229, while the

number of unmarried men is only 125. A glance at the tables which

show their scanty earnings, and the numerous families which are

dependent upon two-thirds of them, will convey a sufficient idea of the

position of moral as well as pecuniary difficulty in which they are

placed. Some of the women included in this class are, indeed, widowed

only by the abandonment of their husbands. All, however, are living

unprotected, with families dependent upon them.

All those specified as unfortunate females appear, with only a few

exceptions, to be persons of respectable outward manners and conduct,

for the houses of prostitution were expressly excepted from inquiry,

beyond a rough enumeration of them and of their inmates, since they

form a distinct feature in society which it was not our present purpose

to investigate. Unhappily there are many houses of this description

within the topographical limits of the present inquiry, frequented

chiefly by sailors, low mechanics, and labourers, at least fifty coming

within the observation of your Committee's agents.

It is a pity

that these houses are 'expressly excepted' - the information would be

interesting. One head of family in Table IV is listed as 'house of ill

fame'.

Although

the numbers below are in some cases too small to be statistically

significant, the report is prescient in separating 'family' and 'single'

occupations. See here for emigration schemes for 'distressed needlewomen'.

The wages are seen to vary (Table VI.) as usual, with the degree of

skill required in the several trades; the lowest being those of the

sailors, 11s. 10d. per week besides rations, and of the mere labourers, 15s. 7d. per week, on the average; the highest, those of the gunsmiths, 41s. 9d. per week; the general average being 20s. 2d. per week. Including the earnings of all the family, the incomes of the sailors average 15s. 4d. per week, of the labourers 19s. Id., and of all the rest, various sums between 20s. and 40s., with the exception of the gunsmiths, whose total emoluments per family average 45s. 3d.

per week. Necessity, on the one hand, in the poorer trades, and

opportunity, on the other, in some of the better paid, cause the amount

of subordinate earnings to equalize each other in the families of some

of the men who earn, themselves, a very unequal amount of wages; while

those unmoved by either peculiar necessity or peculiar opportunity,

show least of pecuniary advantages derived from the labour of women and

children. In a few cases, the earnings of a grown up-son give an excess

which disturbs the average from its usual value as an index to the

earnings of women and children, and it must carefully be borne in mind

that there may be the most industry, and that of the most appropriate

kind, in those families whose subordinate members add little or nothing

to their pecuniary resources; for the labours and cares of the little

household, in homes which can afford the employment of only casual if

any domestic service, are quite sufficient to occupy all available time

and ability in their proper discharge. In the case of the tailors, the

proportion of the wife's earnings is greater than would appear from the

table, because the females assist the men in the work, for which

payment is entered under the head of the husband's wages; but, in all

other cases, the additional sums are drawn from the sources indicated

in the case of the unprotected women.

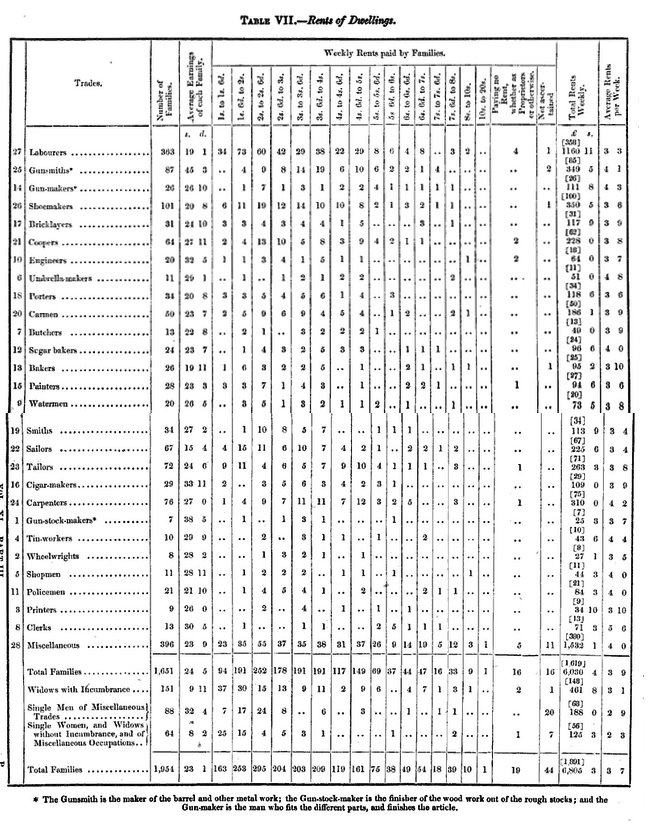

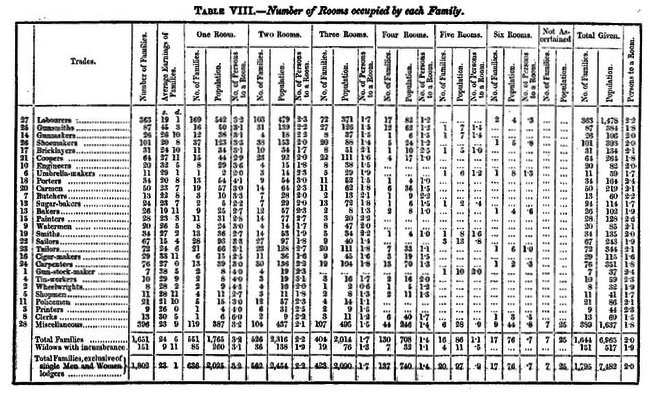

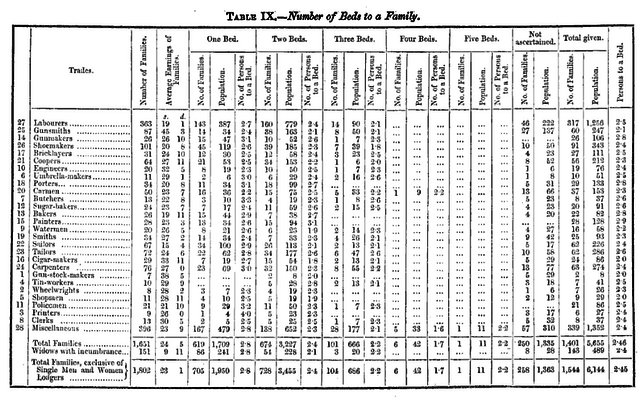

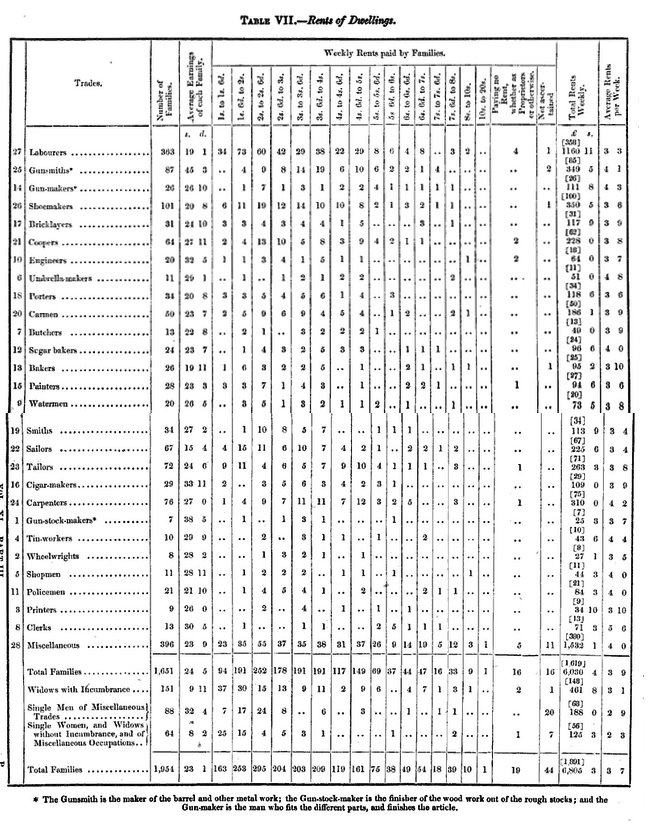

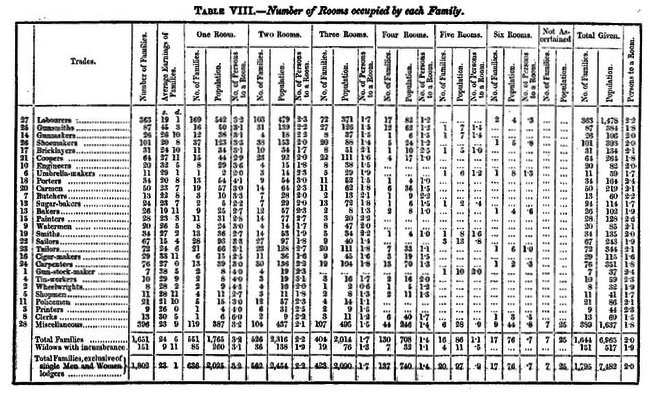

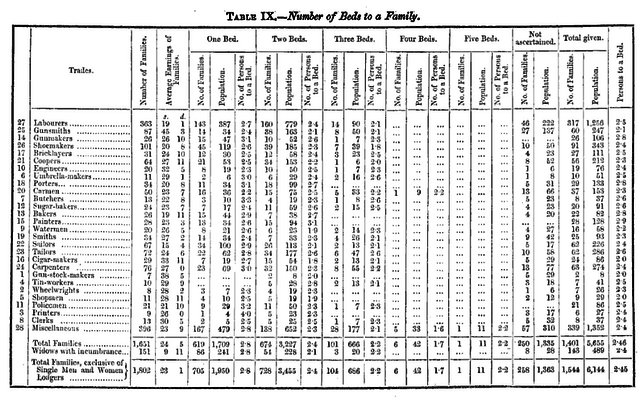

The preceding table (VII.) shows, in comparison with the average

earnings of the families in each trade, their weekly payments for rent,

carefully classified; the next following (VIII.) shows the number of rooms

occupied by the families, and the number of persons to a room; while a

third (IX.) states the number of beds possessed by each, and the number of

cases where there are one, two, three, or any greater number of persons

to a bed. The only remarkable result is the moderate degree of crowding

which prevails throughout the population. It is greatest, of course, in

the families having only one room, with several little children, but it

steadily decreases as each class increases in the number of its rooms

and its beds, showing that this is a population entirely above the

wretched system of sub-letting corners of the same room, which

occasions such an accumulation of wretchedness, barbarism, and disease,

in the few localities to which the rudest and most unsettled of the

population resort. Want of space and ventilation in the rooms is,

however, observed generally, and everyone can conceive how unfavourable

it is to domestic quiet to have only one room for every purpose of

repose and the ménage.

Indeed, the possession of only one room, indicates a depression of

habits and of health, which, if every grosser feature of misery were

removed, would well deserve the solicitude of the philanthropist; the

provision of a second room in town-life being as marked a step as the

advancement from a hovel to a proper cottage in the country.

The preceding table (VII.) shows, in comparison with the average

earnings of the families in each trade, their weekly payments for rent,

carefully classified; the next following (VIII.) shows the number of rooms

occupied by the families, and the number of persons to a room; while a

third (IX.) states the number of beds possessed by each, and the number of

cases where there are one, two, three, or any greater number of persons

to a bed. The only remarkable result is the moderate degree of crowding

which prevails throughout the population. It is greatest, of course, in

the families having only one room, with several little children, but it

steadily decreases as each class increases in the number of its rooms

and its beds, showing that this is a population entirely above the

wretched system of sub-letting corners of the same room, which

occasions such an accumulation of wretchedness, barbarism, and disease,

in the few localities to which the rudest and most unsettled of the

population resort. Want of space and ventilation in the rooms is,

however, observed generally, and everyone can conceive how unfavourable

it is to domestic quiet to have only one room for every purpose of

repose and the ménage.

Indeed, the possession of only one room, indicates a depression of

habits and of health, which, if every grosser feature of misery were

removed, would well deserve the solicitude of the philanthropist; the

provision of a second room in town-life being as marked a step as the

advancement from a hovel to a proper cottage in the country.

The average rent is seen to be no less than 3s. 7d. per week, or 9l.

6s.4d. per year, which, on the total number of families (1,954),

gives the enormous sum of 18,204l. 16s. 8d. The present Committee, in

relation to this subject, would earnestly recal [sic]

the attention of the Members of the Society to the practical suggestion

contained in the Report of their Committee on the state of the working

classes in the parishes of St. Margaret and St. John, Westminster, read

at the Ordinary Meeting of the Society on the 16th of March, 1840, and

which has already been the source of much good in the origination of

societies for the improvement of the dwellings and the lodging-houses

of the labouring classes, and offers a test from which yet more

enlarged practical deductions might be drawn, at a time when express

provisions for the physical and moral health of our vast urban

populations are at length recognised as a part of the public policy of

the empire:

High rents are an evil of a practical

nature from which the labouring classes are severely suffering; and a

sufficient proof of this circumstance is afforded in the fact that

large numbers of the families of the working population continue to

reside, for months and years together, crowded within miserable

dwellings, consisting of a single room, of very moderate size, for each

family. As a remedy for such

an obvious grievance, the Committee are desirous to show the advantage

which may be derived from the outlay of a moderate amount of capital,

in the erection of buildings containing sets of rooms suited to the

accommodation of labouring families in properly selected situations.

For these dwellings, weekly rents should be required from the tenants,

and a profit may, in this manner, be reasonably expected from capital

judiciously invested, while advantages of still greater importance,

both physical and moral, would be gained to society from the removal of

a serious cause of discontent among the working classes, and from the

provision of a more correct and convenient arrangement of their

household comforts, which may materially assist in the foundation of a

superior moral character for the working population.

See here for a brief history of 'model dwellings', and here for later developments in this parish.

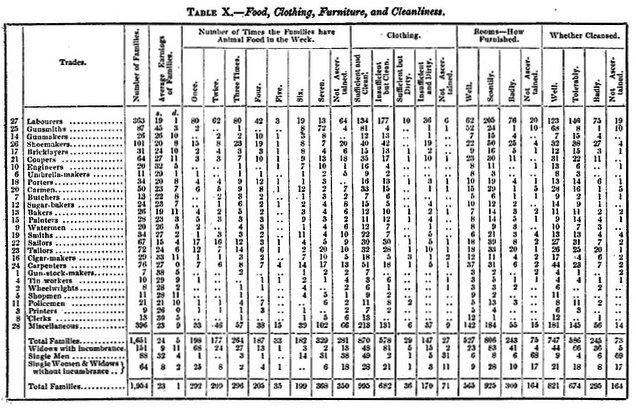

The state of these poor families, with regard to food, clothing,

furniture, and cleanliness, is described in Table X. There seems

to be indicated by the column showing the consumption of animal food, a

classification into poor and sufficient feeding; the former being very

clearly indicated by the two columns which represent those who very

clearly by represent obtain animal food only once or twice a week;

being about one fourth of the whole. None appeared to be over-fed. The

state of the clothing is, in one sense, more satisfactory; for while it

is described as sufficient in 1,031 cases, and insufficient in 852, it is described as dirty

in only 36 of the former cases, and 170 of the latter. The distribution

of these latter numbers chiefly among the poorer occupations will be

seen at a glance. Only 300 are returned as having rooms ill furnished, while 565 have rooms well furnished, but a number greater than both of these combined (925) are described as having only scanty

furniture; terms which are tolerably expressive to those accustomed to

visit the habitations of the poor. Ill furnished dwellings are those in

which there are only a wretched bedstead, or a bed on the floor, a few

broken chairs, and a table worth only a shilling or two, besides,

perhaps, a box or chest with a few paper pictures about the walls.

Scantily furnished dwellings are those which contain a few chairs, a

deal table, a flock bed, and a few cooking utensils, altogether

indicating a struggle towards neatness, though scarcely towards

comfort. While the dwellings described as well furnished had, perhaps,

a chest of drawers, a clock, really good tables, a carpet, mahogany

chairs, and every article essential to comfort, and some even of

luxury, such as a piano, violins, and other musical instruments, with

foreign productions of curiosity, &c.

The state of these poor families, with regard to food, clothing,

furniture, and cleanliness, is described in Table X. There seems

to be indicated by the column showing the consumption of animal food, a

classification into poor and sufficient feeding; the former being very

clearly indicated by the two columns which represent those who very

clearly by represent obtain animal food only once or twice a week;

being about one fourth of the whole. None appeared to be over-fed. The

state of the clothing is, in one sense, more satisfactory; for while it

is described as sufficient in 1,031 cases, and insufficient in 852, it is described as dirty

in only 36 of the former cases, and 170 of the latter. The distribution

of these latter numbers chiefly among the poorer occupations will be

seen at a glance. Only 300 are returned as having rooms ill furnished, while 565 have rooms well furnished, but a number greater than both of these combined (925) are described as having only scanty

furniture; terms which are tolerably expressive to those accustomed to

visit the habitations of the poor. Ill furnished dwellings are those in

which there are only a wretched bedstead, or a bed on the floor, a few

broken chairs, and a table worth only a shilling or two, besides,

perhaps, a box or chest with a few paper pictures about the walls.

Scantily furnished dwellings are those which contain a few chairs, a

deal table, a flock bed, and a few cooking utensils, altogether

indicating a struggle towards neatness, though scarcely towards

comfort. While the dwellings described as well furnished had, perhaps,

a chest of drawers, a clock, really good tables, a carpet, mahogany

chairs, and every article essential to comfort, and some even of

luxury, such as a piano, violins, and other musical instruments, with

foreign productions of curiosity, &c.

The rooms are badly cleaned in a greater number of cases than the

clothing, viz., in 295, and in 674 they are but tolerably clean. Still,

in one half of the cases ascertained (821), they are described as well

cleaned. The excess of inferior habits in the lower occupations will be

traced generally. The casual dock labourers appear to be in the lowest

condition, in proportion even to their poor means; while those whose

homes are most comfortable, in proportion to their earnings, are

undoubtedly the German sugar-bakers, and the mates of vessels, with

only a part of the gunsmiths; others throwing away all the advantages

of their superior earnings by thriftless habits.

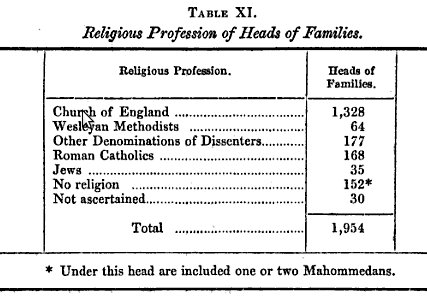

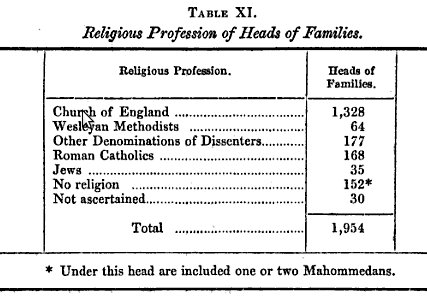

Some evidence as to the religious and moral character of the people

will be conveyed by the table which describes their profession of

religion, the newspapers and periodical publications which they read,

and the character of the books and pictures found in their apartments.

This extensive profession of attachment to the Gospel is a hopeful

sign, though the limited extent to which the Wesleyans and other

denominations of Dissenters, appear to have penetrated into this mass

of population, is rather remarkable, and will justify a feeling of

doubt with regard to the profession made by some of belonging to the

Established Church.

This extensive profession of attachment to the Gospel is a hopeful

sign, though the limited extent to which the Wesleyans and other

denominations of Dissenters, appear to have penetrated into this mass

of population, is rather remarkable, and will justify a feeling of

doubt with regard to the profession made by some of belonging to the

Established Church.

There is reason to believe, however, that the above statement gives a

very fair representation of the results which would be arrived at

amidst large bodies of the working classes, whether in town or country;

though a different result would probably be shown in the manufacturing

districts.

Given the

large number and variety of dissenting and nonconformist chapels in the

area (which makes singling out Wesleyan Methodism misleading), many of

which were more congenial to the poor than the 'mighty' Church of

England, adherence at roughly 10% of that of the established church is

perhaps surprising. But these were churches requiring definite

membership, unlike the 'hatching, matching and dispatching' of nominal

Anglicans, so the 'feeling of doubt' is justified. See here

for rather different figures from the 1851 religious census across the

whole parish, and here for the first of four pages on dissenters in the parish. The presence of Roman Catholics was already significant,

but of Jews still modest; and Muslims are included under 'no religion'

as an oddity, despite (or perhaps because of?) a number of lascar seamen in the surrounding area.

The following are the periodical publications in use among population:—

The following are the periodical publications in use among population:—

This is not a cheering picture; the great use made of the capacity to

read being, so far as this statement indicates, in ministering to mere

excitement. Out of 1,260 cases in which the circumstances with regard

to reading were ascertained, it was wholly in "Lloyd's Gazette", the

"Weekly Dispatch", and the "Advertiser", in every case, except 22 in

which the "Times" is read, 34 in which other miscellaneous prints are

taken in, and only 29 in which no newspaper whatever is read.

'Mere

excitement' seems a harsh judgement: it is surely remarkable that over

half the households took newspapers of some kind, and hardly surprising

that only a few read the market leader, the heavyweight Times (first appearing under this title in 1788). There were seven morning dailies at this time: Times, Morning Advertiser, Morning Herald, Morning Chronicle, Morning Journal, Morning Post, and Public Ledger. Of these, the Times' daily circulation in 1846 was 28,594, against 38,969 for all the others; but by 1854 The Times was selling 51,648, against 26,000 for the rest, of which only the Morning Advertiser's circulation had risen. The local popularity of Lloyd's Gazette (first published as Lloyd's News in 1696, becoming Lloyd's List & Shipping Gazette

in 1734) was that it combined general and shipping news - it would not

have predominated elsewhere. Next most popular here was the Weekly Dispatch,

published in Fleet Street from 1801 with 4 pages at 6d., and perhaps

the first 'modern' newspaper, since it aimed to be 'at once instructive

and entertaining', with 'sporting intelligence' - including boxing -

and lighter news ('occurrences of a subordinate kind') as well as

parliamentary reports from its own reporter. It promised to 'convey the

most authentic, interesting and useful information up to the very

moment of being put to press; every great event occurring on the

Continent of Europe and in all places where our Naval and Miltary

Operations are carried on; every question of War or Peace and

everything connected with the interests of the British Empire', and to

be politically independent, unconnected with factions or parties. The Morning Advertiser was

the 'pub paper', first published in 1794 by the Society of Licensed

Victuallers and available in every bar. It majored on trade interests

rather than party politics, and was heavily promoted by the Society, so

although it was not read in places of influence its circulation rose

during this period. Charles Dickens was a contributor. The title

remains, as a weekly magazine for the pub trade.

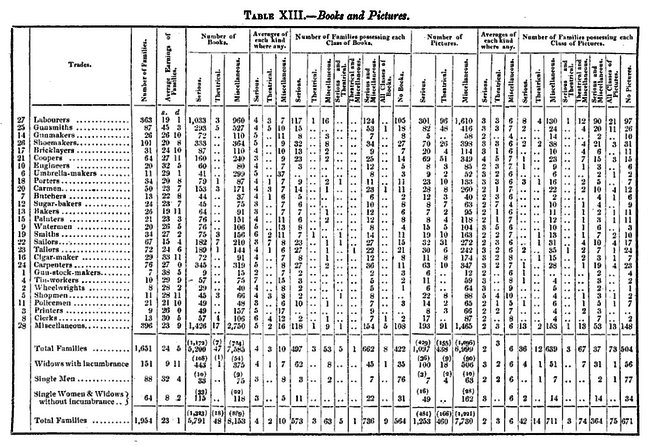

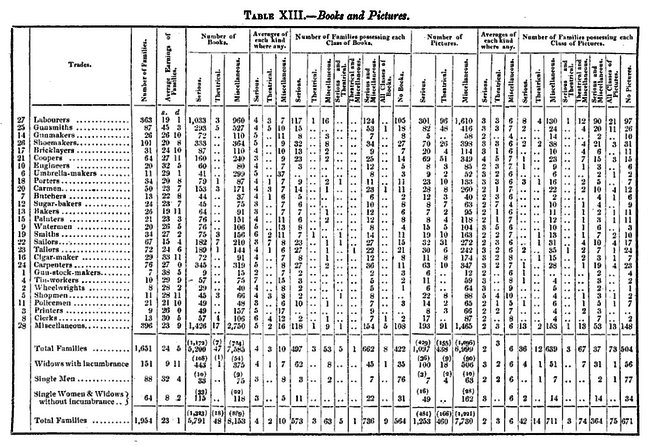

The classification of the books and pictures found in the houses, which

has been adopted in the accompanying table, has been made in deference

to a former classification in like inquiries. The head "Miscellaneous"

is designed to include the miscellaneous books, chiefly of narrative,

and seldom of "useful knowledge", which are found in the houses of the

poorer classes, distinct from the books of religion and morality

comprised under the name of "serious", and the melodramatic works

which, chiefly, are designated by the term "theatrical". The total

number of books found in the district was no less than 13,992, giving

an average of upwards of 11 for each of the families in which they were

found; 564 appearing to be without books of any kind; a proportion

upwards of one fourth of the total number. Only 58 books were found to

be theatrical, while 5,791 are classed as serious, and 8,153 as

miscellaneous. The former were found in only 18 families of the whole

number visited, while all three classes were found in 9 of these;

serious as well as theatrical in 5 more of them; and miscellaneous as

well as theatrical in another; leaving but 3 in which theatrical books

only were found. Both serious and miscellaneous books were found in 736

families; serious books only in 573; and miscellaneous books only in

63. The possession of books is, in fact, almost universal; and in the

families in which each kind of books was found at all, therefore, there

were on an average, 4 serious, 10 miscellaneous, and 3 theatrical. The

extent to which the habit of reading prevails, challenges, therefore,

still more minute investigation into the direction given to it, an

investigation which should extend to some simple observation upon the

apparent use, as well as the actual possession, of the books, and a

yet further classification of them. It is more than one-fourth of the

houses which are without "serious" books, under which name are

generally included the Holy Scriptures and books of prayer; and to what

extent these are really used it must be impossible to ascertain

statistically, but it would be very important to determine whether or

not they appeared to be most used in the houses where they were

accompanied by an equal or perhaps greater proportion of miscellaneous

books. The impression of the agents is, that, in far the greater number

of families which they visited, of all the books which they found in

them, the "Bible" and "Testament" were those least read.

The decoration of the walls with pictures prevails to nearly the same

degree as the possession of books of some kind. The total number of

pictures observed was no fewer than 9,443, of which 7,730 had

miscellaneous, 1,253 serious, and 460 theatrical subjects; the

proportions of the miscellaneous and theatrical being greater in the

pictures than in the books; the numbers of each kind in the families

where they were found at all, averaging, of the serious 2, of the

theatrical 3, and of the miscellaneous 6. These numbers give upwards of

8 to a family, in the case of all the families indulging in this sort

of decoration. In the abodes of 75 families were found pictures of all

these denominations; in 364, serious and miscellaneous pictures; in

711, miscellaneous pictures only; in 74, miscellaneous and theatrical;

in 42, pictures on religious subjects only; in 14, on theatrical

subjects only; in 3, on both serious and theatrical subjects. In 671,

or one-third of the abodes, there was no decoration whatever by

pictures. Those usually found were little paper prints, tricked out in

glaring colours, and enclosed in little black frames of wood; while a

few, especially the marine prints, were really good.

Such detailed

gathering and classifying of information would hardly be possible today

- though the comment about the unread Bible still rings true!

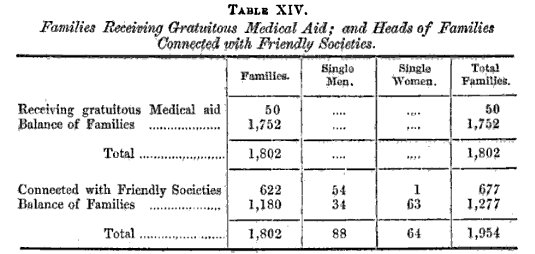

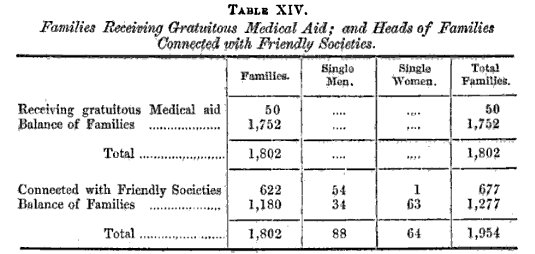

One very gratifying fact is that 622, or upwards of one-third of the

heads of families are connected with Benefit Societies. On the other

hand, however, 50 families were in the actual receipt of gratuitous

medical relief.

One very gratifying fact is that 622, or upwards of one-third of the

heads of families are connected with Benefit Societies. On the other

hand, however, 50 families were in the actual receipt of gratuitous

medical relief.

See here for more on friendly societies, and here for an example of a local medical charity. A generation later dispensaries for the 'deserving poor' were being promoted by those who opposed universal relief.

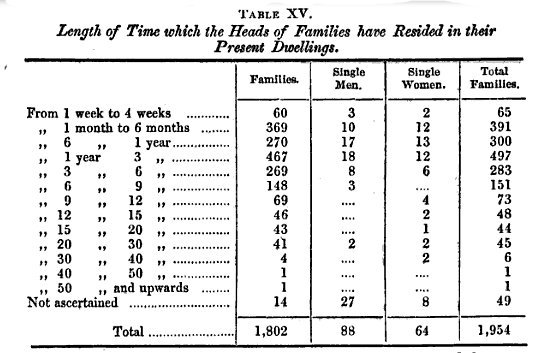

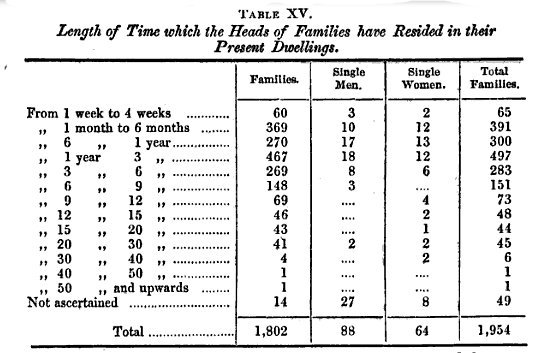

Again, the great length of time which a large proportion of them have

occupied their present habitations, indicates, in the main, a

steadiness of character which is worthy of observation, if we take into

account the large proportion of forced migration which attaches to a

number of the trades; if only from one part of the town to another.

Again, the great length of time which a large proportion of them have

occupied their present habitations, indicates, in the main, a

steadiness of character which is worthy of observation, if we take into

account the large proportion of forced migration which attaches to a

number of the trades; if only from one part of the town to another.

The pattern of

'forced migration' in search of work was certainly prevalent; equally,

many families moved from house to house within just a few streets, as

family and other circumstances changed.

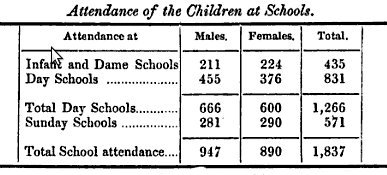

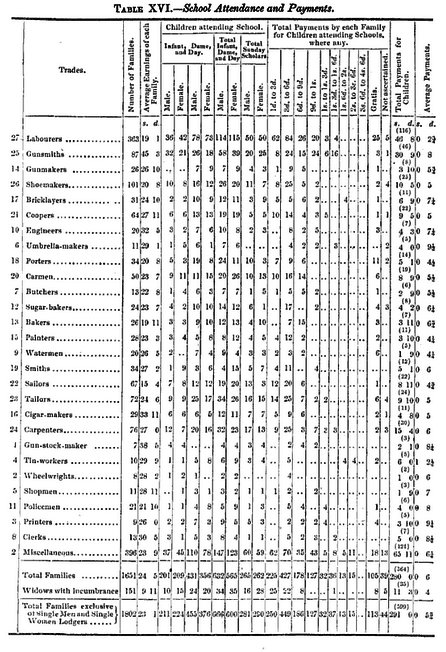

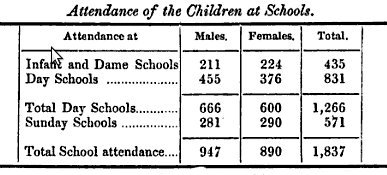

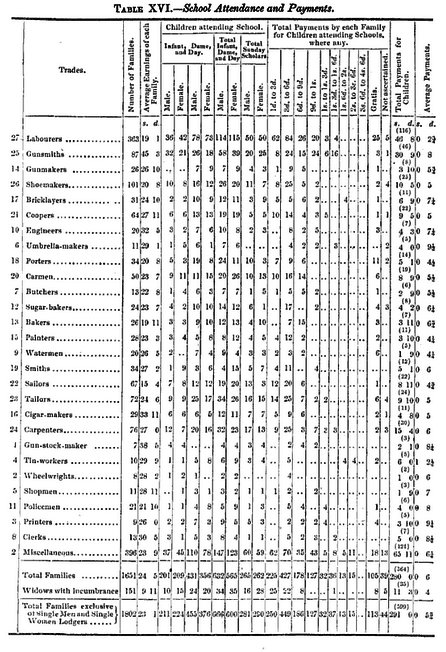

The tables of the attendance of the children in schools, and the payment made by their parents for that attendance, are very

interesting; indicating, as they do, an universal use of schools for

some period of life, and obviously also for successive years. Of the

quality of the schooling we have other and less flattering means of

judging, by analogy.

The tables of the attendance of the children in schools, and the payment made by their parents for that attendance, are very

interesting; indicating, as they do, an universal use of schools for

some period of life, and obviously also for successive years. Of the

quality of the schooling we have other and less flattering means of

judging, by analogy.

Thus, upon the total population of 7,711, the attendance in day-schools

is nearly 1 in 9; in infant and dame schools about 1 in 18; and in

both combined 1 in 6, or approaching one-half of the number not

exceeding 16 years of age. The number of young persons attending Sunday

Schools is seen to be 571, or 1 in 13½ of the whole population, and 1

in 6 of the population not exceeding 16 years of age. Thus, the school

attendance is respectable, even as shown by that in day-schools only,

and when the "out-of-the-way schools" for the "little ones" are

included, it is seen to wear an aspect which is unrivalled even by the

most glowing statistics of voluntary education, in which they

universally form so great a portion; probably, as here, about one

third. The Sunday School attendance is, without doubt, proportionably

less here than in the manufacturing districts, because the absence of

an extensive demand for juvenile labour relieves the pressure for

secular instruction on the Sunday, which causes no small part of the

excess in those districts.

This is a reminder of the origin of Sunday Schools, to offer basic education as well as religious instruction. See here for more detail about the schools in the parish at this period.

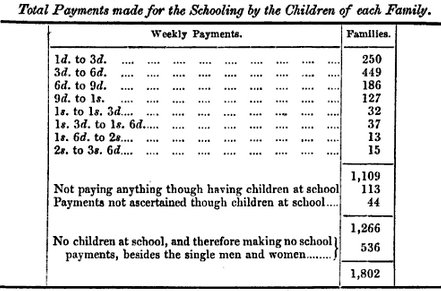

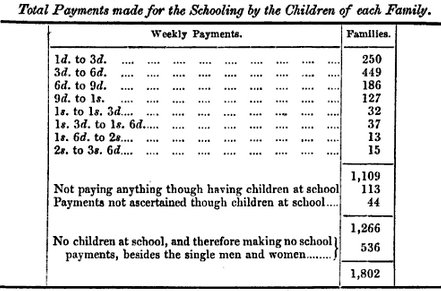

The table of school payments affords a very interesting view of the

payments which the several classes of families are willing to make for

the schooling of their children, while of all the families returned the

children of only 13 were receiving absolutely gratuitous education.

The table of school payments affords a very interesting view of the

payments which the several classes of families are willing to make for

the schooling of their children, while of all the families returned the

children of only 13 were receiving absolutely gratuitous education.

The total sum spent upon day schooling is thus 291s. = 14l. 11s. per week, or 1,056l. 12s. per annum, at a general average of 5¾d.

per week, contributed by each family which pays for schooling at all,

an amount which if distributed over all the families, would be under 2d. per week each.

The rest of

the report is a detailed statistical analysis linking parental age (and

occupation) with family size, to demonstrate a fairly obvious point

(which is why these complex tables are not included here): namely, that

the earlier a family is started, the larger it is likely to be. It then

considers the impact of this on infant and adult mortality, and on

health generally. It reaches the surprising conclusion that infant

mortality rates in the area surveyed are lower than in some more

affluent areas, and that children appear to be healthier than might be

expected given their environment; less surprisingly, adult mortality was high.

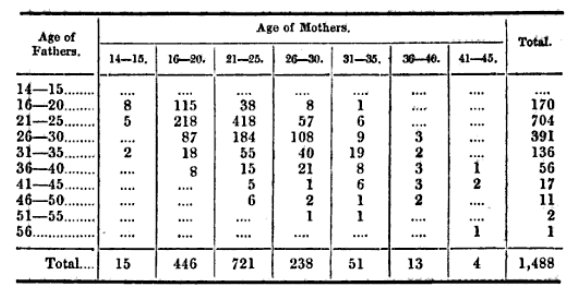

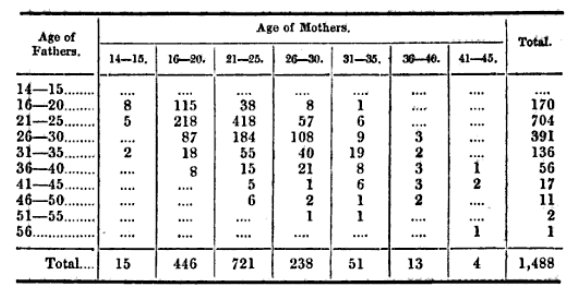

The following table will show the ages

of the parents at the birth of their first child; and if it be

assumed, that the birth of the first child, on the average, happened

about one year after marriage, it will be seen that in both sexes the

greatest number of marriages took place, between the ages of 21 and

25. However, it will be found that the marriages in the male sex have

taken place generally at a much later period in life than among the

female sex, for while out of 1,488 marriages 170 only of the males

were under 20 years of age, as many as 461 females were under the

same age. On the other hand, while 236 only of the females were

between the ages of 26-30, there were as many as 391 males at those

ages. Again, while there were only 68 females married above the ages

of 30, it will be found that as many as 223 males were married above

that age.

The following table will show the ages

of the parents at the birth of their first child; and if it be

assumed, that the birth of the first child, on the average, happened

about one year after marriage, it will be seen that in both sexes the

greatest number of marriages took place, between the ages of 21 and

25. However, it will be found that the marriages in the male sex have

taken place generally at a much later period in life than among the

female sex, for while out of 1,488 marriages 170 only of the males

were under 20 years of age, as many as 461 females were under the

same age. On the other hand, while 236 only of the females were

between the ages of 26-30, there were as many as 391 males at those

ages. Again, while there were only 68 females married above the ages

of 30, it will be found that as many as 223 males were married above

that age.

Tables A, B,

C, D, and E [not included here] exhibit facts of considerable interest and importance,

They are arranged to show the influence of the age at marriage on the

number of children born, and the mortality of those children. Table A

represents the results of those marriages, in which the birth of the

first child took place when the mother was between the ages 16-20.

The first column represents the number of years which have elapsed

since the birth of the first child. The Second—The

number of families over which the observations extend; the Third

—The number of

children born; the Fourth—The

number of children then alive; the Fifth—The

number dead; the Sixth—The

rate of mortality per cent., and the Seventh—The

average number of children born to each family within the given

periods of years set forth in the first column, as having elapsed

since the birth of the first child. Tables B, C, and D represent the

same class of facts for families in which the birth of the first

child took place between the quinquennial ages 21-25, 26-30, and

31-35; and Table E includes the results for all the marriages formed

at whatever period of life they may have taken place.

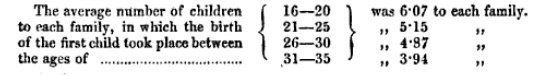

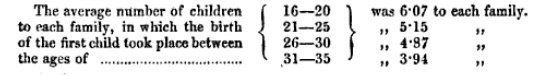

Tables a, b, c, d, and e [not included here] are

abridgments of the preceding tables. The first point deserving of

attention in those figures is the circumstance that those marriages

formed at an earlier period of life are more prolific than those

formed at a later period. The gross results for each group of facts

is as follows: —

Tables a, b, c, d, and e [not included here] are

abridgments of the preceding tables. The first point deserving of

attention in those figures is the circumstance that those marriages

formed at an earlier period of life are more prolific than those

formed at a later period. The gross results for each group of facts

is as follows: —

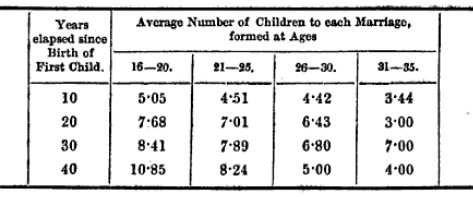

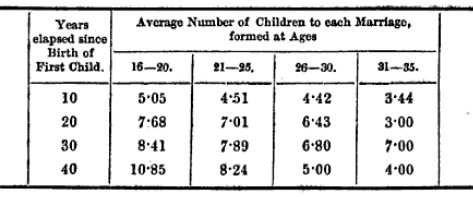

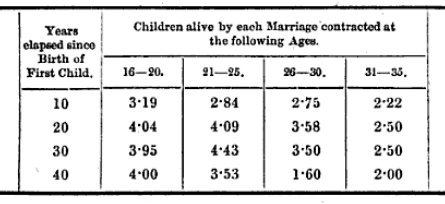

To the results presented in this form,

however, it may be objected, that the number of years elapsed between

the birth of the first child over the time to which the facts are

collected, is, on the average, greater in the case of the earlier

marriages than in the later, and hence the greater number of

children. This objection, true in principle, will be found, under a

closer analysis of the figures, to materially alter the relative

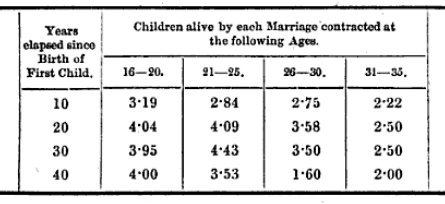

bearing of the results. The following abstract will show the average

number of children to each marriage, at the respective periods of 10,

20, 30, and 40 years after the birth of the first child, for each

class of marriages formed at the four different quinquennial periods

of life.

It is thus

obvious, that marriages formed under the age of 25, are more prolific

than those formed after that age, and that those formed between 16

and 20 years of age are still more so than those at any of the

superior ages.

It is thus

obvious, that marriages formed under the age of 25, are more prolific

than those formed after that age, and that those formed between 16

and 20 years of age are still more so than those at any of the

superior ages.

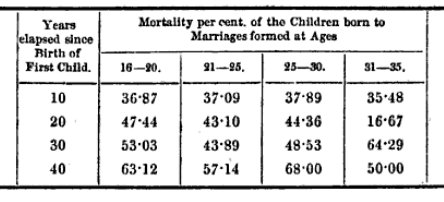

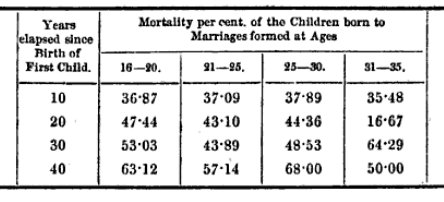

In connexion with these results, it is

important to view the rate of mortality of the children born in

marriages contracted at the same period of life.

These figures are of course subject to

the objection just alluded to, but the following abstract will show

the results in a corrected form.

From this

abstract it is obvious, that of the three first periods, the children

born of marriages formed in the quinquennial term of life, 21-25, are

subject to a less rate of mortality than those of the period

immediately preceding or immediately followingm the rate of mortality

in the most advanced period 31-35, is very irregular, and no doubt

arises from the small number of families included in that group. The

two preceding series of facts furnish materials for the solution of a

very interesting and highly important question, namely, what is the

effect of the marriages formed at those different terms of life on

the ultimate increase of population? By the first of the two

preceding abstracts it was found, that the earlier the period of life

at which marriage was contracted, the greater the number of children

born; but by the second abstract a difference is observable in the

rate of mortality of the various periods, and this must disturb the

results in the first class of facts.

From this

abstract it is obvious, that of the three first periods, the children

born of marriages formed in the quinquennial term of life, 21-25, are

subject to a less rate of mortality than those of the period

immediately preceding or immediately followingm the rate of mortality

in the most advanced period 31-35, is very irregular, and no doubt

arises from the small number of families included in that group. The

two preceding series of facts furnish materials for the solution of a

very interesting and highly important question, namely, what is the

effect of the marriages formed at those different terms of life on

the ultimate increase of population? By the first of the two

preceding abstracts it was found, that the earlier the period of life

at which marriage was contracted, the greater the number of children

born; but by the second abstract a difference is observable in the

rate of mortality of the various periods, and this must disturb the

results in the first class of facts.

Let a represent the results given in

the first abstract; b represent those given in the second; then a - [a × b over 100] = the actual increase resulting from each

marriage to the population. The following is an abstract of the

results thus arrived at:

It hence

follows, that marriages formed under 25 years of age increase the

population more than those formed above that age; and on a close

examination it will be found, that there is very little difference in

this respect between marriages contracted at ages 16-20 and 21-25,

the rate of increase, however, being somewhat higher in the former

period. With regard to the last two quinquennial terms at which

marriage is formed, it will be seen that the rate of increase is not

so great for ages 26-30 as in that immediately preceding, and in the

period 31-35 the rate of increase is still less; in fact, the earlier

the period of marriage the greater the increase resulting to the

population, the difference between the first and second periods being

very little, between the second and third very considerable, about 23

per cent., and between the third and fourth about 20 per cent.

It hence

follows, that marriages formed under 25 years of age increase the

population more than those formed above that age; and on a close

examination it will be found, that there is very little difference in

this respect between marriages contracted at ages 16-20 and 21-25,

the rate of increase, however, being somewhat higher in the former

period. With regard to the last two quinquennial terms at which

marriage is formed, it will be seen that the rate of increase is not

so great for ages 26-30 as in that immediately preceding, and in the

period 31-35 the rate of increase is still less; in fact, the earlier

the period of marriage the greater the increase resulting to the

population, the difference between the first and second periods being

very little, between the second and third very considerable, about 23

per cent., and between the third and fourth about 20 per cent.

In the

consideration of these facts and observations, although they relate

to 1,506 families, from which have resulted 8,034 births, and of

which 4,616 children, or 57∙46

per cent., are still alive, it must be borne in mind that they

include only one class of the community, and may be subject to

disturbing influences, such as to destroy their character as a type

of the general population; however, there is reason to suppose that

these results may be a more faithful representative of the condition

of the whole population, than if they were derived from a like number

of facts from either the middling or higher classes of Society. On

reflection it will also be found, that the unfruitful marriages are

not included in any of those 1,506 families, all included being more

or less productive. Likewise, the marriages are all those in which

one or both the parents are still alive, and consequently the results

of fruitful marriages, in which the parents have died before the

lapse of the given period of years brought under review, are

excluded. An influence, independent of the relative number of

marriages at each age, will further affect the results arising from

the varying rates of mortality at the different terms of life, even

when equal numbers only at those periods are considered; and it will

follow, that fewer marriages of limited fruitfulness will be excluded

from the groups at the younger ages, the effect of which must be to

show in the preceding figures a reduced ratio of children at each

marriage formed at those periods of life, compared with that which

would appear were all cases included. The relative bearing of all the

results are therefore so far modified. Also, the children still

alive, composing 57∙46

per cent. of all born, may, subsequent to the period now under

observation, and when classified according to the ages at marriage of

their parents, show a very

different rate of mortality from that indicated in the respective

classes by those who have hitherto died, and still more extended

observations would be required to show, whether any and what

difference exist, in the fruitfulness of the marriages in the

succeeding generation. Lastly, all these remarks have had reference

to the age of the mother only at birth of her first child.

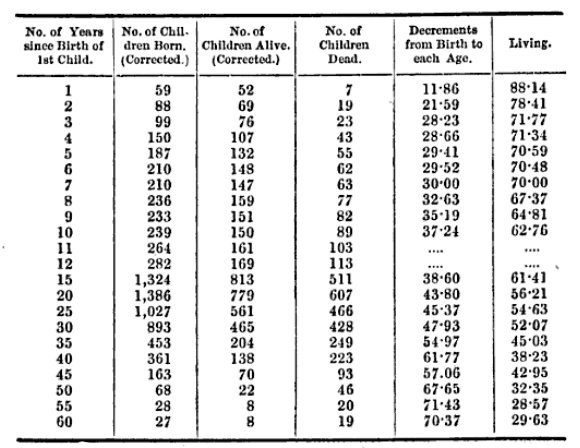

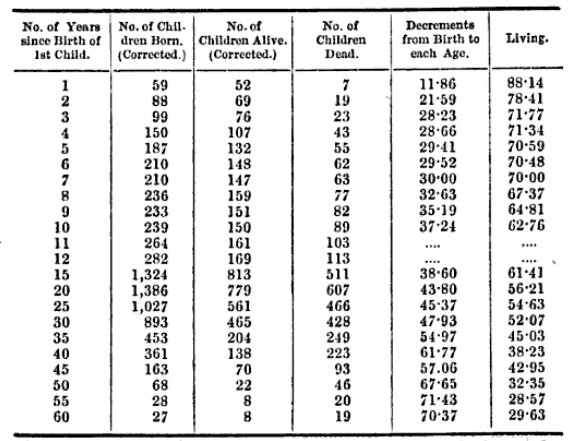

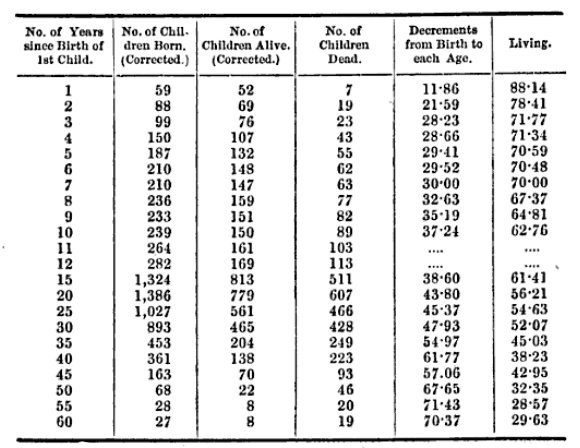

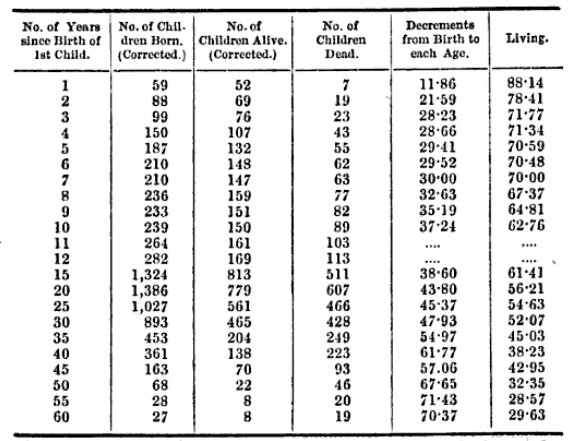

The next point to which attention is

directed, is the rate of mortality experienced by the children of

those families. This will be seen by an inspection of Tables A, B, C,

D, and E, as well as the abridgments of those tables, but as these,

from their peculiar construction, as well as from the small number of

families in some of the years, cause various irregularities in the

results, the following graduated abstract will exhibit the rate of

mortality for all the groups included in the preceding tables. The

mortality in the first year of life appears to be remarkably low,

being only 11∙86 per

cent., while, according to the Fourth Report of the

Registrar-General, the mortality during the first year of life was

for—

England and Wales

17∙355 %

For the County of Surrey 13∙278

%

For the Metropolis 20∙124

%

For Liverpool 28∙157

%

It will further be seen from the

following abstract, column 6, that of 100 children born, 62∙76

live to complete their tenth year:

but according to the same report of the

Registrar-General, the number out of 100 born who live to complete

their tenth year is,—

For England and Wales

70∙61 %

For the County of Surrey 75∙42

%

For the Metropolis 64∙92

%

For Liverpool 48∙21

%

while according to the following

well-known life-tables, the number out of 100 born who live to

complete their tenth year is by the—

Carlisle Table (Milne)

64∙60 %

Sweden (Nicander) 63∙03

%

Select Lives in France (Deparcleux)

60∙04 %

Towns in France (Duvillard) 55∙11 %

Northampton (Price) 48∙71 %

Montpellier (Monyue) 43∙58

%

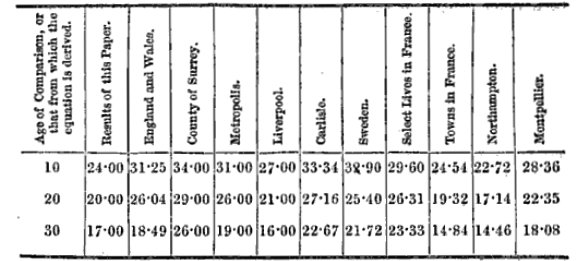

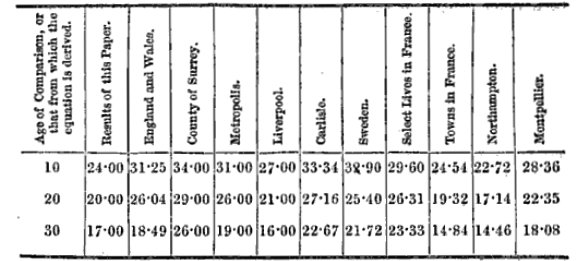

Again, the numbers living to complete

their 20th and their 30th years, according to each of the above

authorities, is as follows:—

Beyond the

age of 30, the facts in this paper are not sufficiently numerous to

warrant a comparison being instituted between them and other life

tables, but from the illustrations already brought forward, it will

be seen that the rate of mortality in the first year of life, is less

than in any other of those cases. Again, with respect to the

decrement of life between birth and the tenth year, it is greater

than that for England and Wales, the county of Surrey, the

Metropolis, the Carlisle Table, and that for the kingdom of Swedenm

but less than the decrement for the select lives in Francem the towns

in France, Northamptonm Liverpool and Montpellier.

Beyond the

age of 30, the facts in this paper are not sufficiently numerous to

warrant a comparison being instituted between them and other life

tables, but from the illustrations already brought forward, it will

be seen that the rate of mortality in the first year of life, is less

than in any other of those cases. Again, with respect to the

decrement of life between birth and the tenth year, it is greater

than that for England and Wales, the county of Surrey, the

Metropolis, the Carlisle Table, and that for the kingdom of Swedenm

but less than the decrement for the select lives in Francem the towns

in France, Northamptonm Liverpool and Montpellier.

With respect to the decrements of life

up to the ages of 20 and 30, they will be found to hold the same

relative situation as that for age 10, being intermediate between

Sweden and the select lives of France.

Those remarks being applicable to all

the changes and fluctuations, taking place from birth up to the

various ages at which the comparisons are instituted, any

irregularity in the mortality of one period, the first year of life

for example, will disturb the results for all the subsequent ages. In

order, therefore, to avoid the effects of the force of this element,

it may be important to test the relative value of the different

classes of facts, by a comparison of the equation of life for the

different mortality tables. The following gives the result thus

arrived at, for one-fourth of the integral or original number.

In viewing

the decrements of life from birth only, it was found that the results

of this paper were intermediate in the scale between the table for

Sweden and that for the select lives in France, that comparison was

of course affected by the rate of mortality in infant life; but in

the above tables, where the results of advanced life only enter into

the figures, it is seen that the mortality is higher than that of all

the tables, except those for the towns of France and for Northampton.

In viewing

the decrements of life from birth only, it was found that the results

of this paper were intermediate in the scale between the table for

Sweden and that for the select lives in France, that comparison was

of course affected by the rate of mortality in infant life; but in

the above tables, where the results of advanced life only enter into

the figures, it is seen that the mortality is higher than that of all

the tables, except those for the towns of France and for Northampton.

It is hence obvious, that so far as the

facts here brought forward can be relied on, the mortality of infant

life is very low, and that of advanced life high.

Lest the results of this inquiry,

however, should be deemed by some to fairly indicate the influence of

locality on the duration of life, of the inhabitants of this district

of Whitechapel, with equal truth for the early and advanced terms of

life, it may be well to draw attention to the following abstract,

showing the length of time which the principal members of families

have resided in their dwellings. [Table XV above has already presented these figures in slightly different form]

It will thus

be seen, that nearly two thirds of the families have been less than

three years in their present residence, and more than one-fourth

between one and three years only. The term "in their present

residence" will admit of the explanation that they may have been

much longer in the same neighbourhood. Still many amongst those who

have changed their dwellings must also have been recent inhabitants

of the locality, and it must therefore follow that the younger lives

indicate more strictly the sanatory [sic] condition of the place than

those of more advanced age. The high rate of mortality of the older

lives now under review can, consequently, not be attributable to

residence in Whitechapel, as the majority of the deaths in advanced

life may have taken place elsewhere—one-thirteenth

only of the families having occupied their present residences upwards

of twelve years; but with respect to the deaths at the younger ages,

the greater number of those must have happened in the locality, and

hence the comparative healthiness of the district.

It will thus

be seen, that nearly two thirds of the families have been less than

three years in their present residence, and more than one-fourth

between one and three years only. The term "in their present

residence" will admit of the explanation that they may have been

much longer in the same neighbourhood. Still many amongst those who

have changed their dwellings must also have been recent inhabitants

of the locality, and it must therefore follow that the younger lives

indicate more strictly the sanatory [sic] condition of the place than

those of more advanced age. The high rate of mortality of the older

lives now under review can, consequently, not be attributable to

residence in Whitechapel, as the majority of the deaths in advanced

life may have taken place elsewhere—one-thirteenth

only of the families having occupied their present residences upwards

of twelve years; but with respect to the deaths at the younger ages,

the greater number of those must have happened in the locality, and

hence the comparative healthiness of the district.

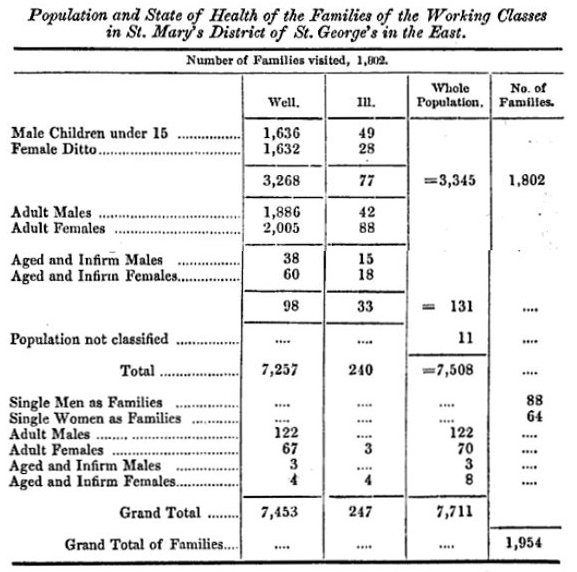

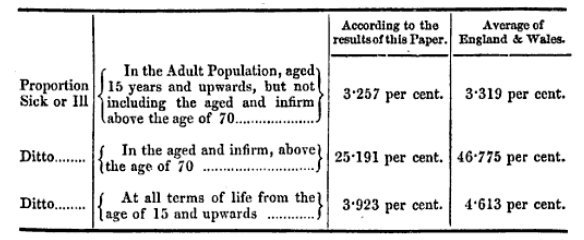

In regard to the state of health of the

families surveyed in the district now under consideration, it may be

interesting to subjoin the following abstract returned "well"

and "ill".

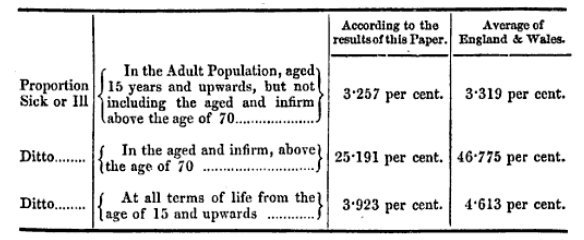

It is thus

seen that of the 7,711 persons here enumerated, 247, or 3∙923

per cent., are returned as being "ill". These numbers

include the children and those under 15 years of age. There is no

authentic record of the proportion constantly sick in this country at

all ages, including the young, but the records of Friendly Societies

will admit of a comparison for every term of life from the age of 10

upwards; and this comparison will, to some extent, be strictly

applicable, from the fact that of the 1,954 families now referred, to

677, or 34∙135, were

connected with Friendly Societies. The following will show the

proportion recorded ill in those families at various terms of life,

as well as the ratio constantly sick for the average of England and

Wales, among the members of Friendly Societies.

So far as

the preceding facts are available as a test of health, it is obvious

that the district now under consideration, must be regarded in a very

favourable light.

So far as

the preceding facts are available as a test of health, it is obvious

that the district now under consideration, must be regarded in a very

favourable light.

Further Tables, not reproduced here:

XVII - Ages of each Parent when first

Child born, Present Age of Parents, Number of Children they have had,

&c. [by occupation]

XVIII - Total of Present Age of Married

Women having no Children, classified according to Trades

XIX - Number of Children Born and

Living in Families, classified by the Mother's Age at the Birth of

the First Child - A 16-20, B 21-25, C 26-30, D 31-35, E Total Ages

14-43

XX - Average Average of Present Age of

Mothers, of Respective Trades Classified, with Averages of Children

Born, now Living, and Dead, to each; also Average Age of Mother when

First Child Bom, with difference between that and Present Age

XXI & XXII - [the same continued]

XXIII - Totals of Present Age of Mothers, of Respective Trades

Classified, with Children Bom, now Living, and Dead; and Total Ages

of Married Women having no Children inserted under Respective

Classified Ages and Trades

XXIV & XXV - [the same continued]

XXVI - Table of present Age of Mothers

of respective Trades, classified with Children Born, now Living and

Dead

XXVII - [the same continued]

Back

to History

The St. Mary's district of St George's in the East was accordingly

selected for the elaborate analysis which it was determined to make;

and the portion concerning which it was ultimately found practicable to

obtain every varied item of information, was the great block of

habitations included between White Horse Lane, which is the

commencement of the Commercial Road, on the north, and Cable Street and

the New Road on the south; and between the New Road on the east and

Church Lane on the west. This is, in fact, the whole of St Mary's

district north of Cable Street; and it is one of those composed of

dingy streets, of houses of small dimensions and moderate elevation,

very closely packed in ill-ventilated streets and courts, such as are

commonly inhabited by the working classes of the east end; and indeed,

it may be said, of all parts of London beyond the limits of that

congested band round its centre, where overcrowding is carried to the

greatest excess.

The St. Mary's district of St George's in the East was accordingly

selected for the elaborate analysis which it was determined to make;

and the portion concerning which it was ultimately found practicable to

obtain every varied item of information, was the great block of

habitations included between White Horse Lane, which is the

commencement of the Commercial Road, on the north, and Cable Street and

the New Road on the south; and between the New Road on the east and

Church Lane on the west. This is, in fact, the whole of St Mary's

district north of Cable Street; and it is one of those composed of

dingy streets, of houses of small dimensions and moderate elevation,

very closely packed in ill-ventilated streets and courts, such as are

commonly inhabited by the working classes of the east end; and indeed,

it may be said, of all parts of London beyond the limits of that

congested band round its centre, where overcrowding is carried to the

greatest excess.

Illness, in the meaning of the following table (II), is such as produces

confinement to the house, and incapacity for labour or exertion. The

proportion of such illness is small; and the appearance of the

children, even, is very healthy, wherever there is a sufficiency of

food; for they are early sent, as much as possible, out of the confined

rooms of their parents, though sometimes into little, filthy, smoky,

dame schools, by no means preferable; except that they have to pass

through the streets to arrive at them. Others of these schools,

however, are clean and fairly ventilated, and kept by persons with

habits of order and propriety.

Illness, in the meaning of the following table (II), is such as produces

confinement to the house, and incapacity for labour or exertion. The

proportion of such illness is small; and the appearance of the

children, even, is very healthy, wherever there is a sufficiency of

food; for they are early sent, as much as possible, out of the confined

rooms of their parents, though sometimes into little, filthy, smoky,

dame schools, by no means preferable; except that they have to pass

through the streets to arrive at them. Others of these schools,

however, are clean and fairly ventilated, and kept by persons with

habits of order and propriety.  The excess of foreigners, indicated by this table (III), is partly

attributable to some foreign sailors having their homes here, but

chiefly to the sugar bakers, being nearly all Germans; and to their

credit it ought to be added, that they are a cleanly, orderly, and well

conducted body of men, chiefly worshippers at the German chapel in the

neighbourhood.

The excess of foreigners, indicated by this table (III), is partly

attributable to some foreign sailors having their homes here, but

chiefly to the sugar bakers, being nearly all Germans; and to their

credit it ought to be added, that they are a cleanly, orderly, and well

conducted body of men, chiefly worshippers at the German chapel in the

neighbourhood.

The preceding table (VII.) shows, in comparison with the average

earnings of the families in each trade, their weekly payments for rent,

carefully classified; the next following (VIII.) shows the number of rooms

occupied by the families, and the number of persons to a room; while a

third (IX.) states the number of beds possessed by each, and the number of

cases where there are one, two, three, or any greater number of persons

to a bed. The only remarkable result is the moderate degree of crowding

which prevails throughout the population. It is greatest, of course, in

the families having only one room, with several little children, but it

steadily decreases as each class increases in the number of its rooms

and its beds, showing that this is a population entirely above the

wretched system of sub-letting corners of the same room, which

occasions such an accumulation of wretchedness, barbarism, and disease,

in the few localities to which the rudest and most unsettled of the

population resort. Want of space and ventilation in the rooms is,

however, observed generally, and everyone can conceive how unfavourable

it is to domestic quiet to have only one room for every purpose of

repose and the ménage.

Indeed, the possession of only one room, indicates a depression of

habits and of health, which, if every grosser feature of misery were

removed, would well deserve the solicitude of the philanthropist; the

provision of a second room in town-life being as marked a step as the

advancement from a hovel to a proper cottage in the country.

The preceding table (VII.) shows, in comparison with the average

earnings of the families in each trade, their weekly payments for rent,

carefully classified; the next following (VIII.) shows the number of rooms

occupied by the families, and the number of persons to a room; while a

third (IX.) states the number of beds possessed by each, and the number of

cases where there are one, two, three, or any greater number of persons

to a bed. The only remarkable result is the moderate degree of crowding

which prevails throughout the population. It is greatest, of course, in

the families having only one room, with several little children, but it

steadily decreases as each class increases in the number of its rooms

and its beds, showing that this is a population entirely above the

wretched system of sub-letting corners of the same room, which

occasions such an accumulation of wretchedness, barbarism, and disease,

in the few localities to which the rudest and most unsettled of the

population resort. Want of space and ventilation in the rooms is,

however, observed generally, and everyone can conceive how unfavourable

it is to domestic quiet to have only one room for every purpose of

repose and the ménage.

Indeed, the possession of only one room, indicates a depression of

habits and of health, which, if every grosser feature of misery were

removed, would well deserve the solicitude of the philanthropist; the

provision of a second room in town-life being as marked a step as the

advancement from a hovel to a proper cottage in the country.

The state of these poor families, with regard to food, clothing,

furniture, and cleanliness, is described in Table X. There seems

to be indicated by the column showing the consumption of animal food, a

classification into poor and sufficient feeding; the former being very

clearly indicated by the two columns which represent those who very

clearly by represent obtain animal food only once or twice a week;

being about one fourth of the whole. None appeared to be over-fed. The

state of the clothing is, in one sense, more satisfactory; for while it

is described as sufficient in 1,031 cases, and insufficient in 852, it is described as dirty

in only 36 of the former cases, and 170 of the latter. The distribution

of these latter numbers chiefly among the poorer occupations will be

seen at a glance. Only 300 are returned as having rooms ill furnished, while 565 have rooms well furnished, but a number greater than both of these combined (925) are described as having only scanty

furniture; terms which are tolerably expressive to those accustomed to

visit the habitations of the poor. Ill furnished dwellings are those in

which there are only a wretched bedstead, or a bed on the floor, a few

broken chairs, and a table worth only a shilling or two, besides,

perhaps, a box or chest with a few paper pictures about the walls.

Scantily furnished dwellings are those which contain a few chairs, a

deal table, a flock bed, and a few cooking utensils, altogether

indicating a struggle towards neatness, though scarcely towards

comfort. While the dwellings described as well furnished had, perhaps,

a chest of drawers, a clock, really good tables, a carpet, mahogany

chairs, and every article essential to comfort, and some even of

luxury, such as a piano, violins, and other musical instruments, with

foreign productions of curiosity, &c.

The state of these poor families, with regard to food, clothing,

furniture, and cleanliness, is described in Table X. There seems

to be indicated by the column showing the consumption of animal food, a

classification into poor and sufficient feeding; the former being very

clearly indicated by the two columns which represent those who very

clearly by represent obtain animal food only once or twice a week;

being about one fourth of the whole. None appeared to be over-fed. The

state of the clothing is, in one sense, more satisfactory; for while it

is described as sufficient in 1,031 cases, and insufficient in 852, it is described as dirty

in only 36 of the former cases, and 170 of the latter. The distribution

of these latter numbers chiefly among the poorer occupations will be

seen at a glance. Only 300 are returned as having rooms ill furnished, while 565 have rooms well furnished, but a number greater than both of these combined (925) are described as having only scanty

furniture; terms which are tolerably expressive to those accustomed to

visit the habitations of the poor. Ill furnished dwellings are those in

which there are only a wretched bedstead, or a bed on the floor, a few

broken chairs, and a table worth only a shilling or two, besides,

perhaps, a box or chest with a few paper pictures about the walls.