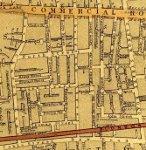

St John's parish

The

area between Backchurch Lane (Church Lane until the 1860s) towards

Cannon Street Road, between Cable Street and the Commerical Road,

became the patch of St John the

Evangelist-in-the-East Grove [Golding] Street; its small streets and courts were densely populated and deeply deprived. Maps right from 1868 and 1878 show street name changes: North Street to Fairclough Street, Sander Street to Charles Street, Elizabeth Street to Stutfield Street, Splidt's Terrace (later Street) to Forbes Street, and Thomas Street to Pinchin Street. Subsequently, Phil(l)ip Street became Philchurch Street.

The

area between Backchurch Lane (Church Lane until the 1860s) towards

Cannon Street Road, between Cable Street and the Commerical Road,

became the patch of St John the

Evangelist-in-the-East Grove [Golding] Street; its small streets and courts were densely populated and deeply deprived. Maps right from 1868 and 1878 show street name changes: North Street to Fairclough Street, Sander Street to Charles Street, Elizabeth Street to Stutfield Street, Splidt's Terrace (later Street) to Forbes Street, and Thomas Street to Pinchin Street. Subsequently, Phil(l)ip Street became Philchurch Street.

Far right is a link to Goad's

1899 insurance map for the northern part of the parish area, which

numbers every property, showing whether it was a dwelling or shop or

workplace, and provides much other information. For example, it shows

the many small and cramped courts built between the main streets and

accessed only by foot through narrow passages: these include, going

from west to east: off Batty Street, Queen Court (also accessed from Christian Street), Batty Place, Batty Court (which housed a club), Hampshire Court (also accessed from Berner Street); off Christian Street, Matilda Street and Matilda Place; Turners Buildings (also accessed from Grove Street); off Grove Street, Durer Place; between Grove and Umberston Streets, Joseph's Terrace (with a cow house and school between Umberston and Morgan Streets); Western Passage; Norman Buildings (accessed from Cannon Street Road); Bowyers Buildings and London Terrace, behind the Cannon Street Road synagogue (see more on the development of this area here); and south of James Street, West('s) Folly, Amber Court, and Langdale Place (accessed from William Street).

The

ground rents for a large number of properties in this area were owned

by one Abraham Batty. 'Abraham Batty of Church-lane, Whitechapel' was a

contributor to the new London Hospital in 1775, and a namesake (son?),

1780-1868, was a market gardener in the area and later in Batty Fields, Bermondsey. In 1879 the Ecclesiastical Review advertised

| Auction Sale. By order of the surviving Trustee of the late Abraham Batty. Esq.—Christian-street, Batty-street, Berner-street, Sander-street, and Commercial-road East.—To Trustees, Capitalists, and others.—Important and highly valuable Freehold Properties. MESSRS. RICE BROTHERS are instructed to offer for SALE, by ACTION, at the AUCTION MART, Tokenhouse-yard, City, on WEDNESDAY, October 29, 1879, at two o'clock precisely, in 17 lots, valuable FREEHOLD GROUND RENTS, amounting to £287 9s. 2d. per annum, arising from and amply secured by first-class shop property, situate and being Nos. 8l, 86, 88, 90, 92, 91, 96, 98, 100, 102, 104, 106, 108, 110, 112, and 114, Commercial-road East, with the premises in the rear thereof, comprising Coopers' Hall, the extensive and well-arranged engineering works, in the occupation of Messrs. Fraser Brothers, capital stabling, &c., together with 10 dwelling-houses, with gardens, Nos. 93 to 111 (being odd numbers), Christian-street; 19 dwelling-houses and other premises, being Nos. 1 to 19 (odd numbers) and 2 to 18 (even numbers) Batty-street; nine dwelling-houses, Nos. 1, 3, 5, 13, 15, 17, and 19, also 12 and 11, Berner-street, with the extensive stabling, yard, dwelling-house, and premises adjoining, with gateway entrance from Berner-street, and private way from Batty-street; also No. 16, Sander-street, Commercial-road East, with reversion in 22.5 years from Michaelmas, 1879, to the rack rentals, estimated at about £3,000 per annum; also three freehold houses, being No. 7, 9, and 11, Berner-street, let at weekly rentals amounting to £106. 6s. per annum.—The estate may be viewed by permission of the respective occupiers, and particulars, with plans and conditions of sale, had of Messrs. Bridger and Collins, Solicitors, 37. King William-street. E.C., at the Mart; and of the Auctioneers. 'The Factory Gazette', Offices, 2, Adelaide-place, London Bridge, City. |

By the time St John's church was built, the area had become squalid. Here is a nonconformist account from The

Christian's Penny

Magazine, and Friend of the People (Congregational Union 1865,

ed J

Campbell), which singles it singles it out as a centre of vice:

| THE EAST OF LONDON No dweller at the West-end, says the Rev. G. W. M'Cree, the missionary of St. Giles's, can have any conception of its crowded apartments, narrow alleys, swarming dogs and children; slaughterhouses reeking with blood; pawnbrokers' shops filled to repletion with the pledges of the poor; factories, yards, and workshops, all noisy, ill-ventilated, and very dirty; crooked, unswept, and unsavoury lanes, where every woman seems consumptive, and every man half-starved; beershops, the haunts of thieves, and ginshops echoing with the gabble and blasphemies of heated, angry, wretched people; the famous 'Highway', with its sailors, crimps, hawkers, soldiers, pickpockets, watermen, negro melodists, butchers' men, Lascars, dock labourers, flaunting women more cruel than tigers, policemen walking in pairs, ship-captains with gay girls hanging on their arms, touts from boarding-houses, grimy stokers, Irish emigrants, beggars, and pugilists—in brief, its noise, dirt, crime, want, disease, and misery. Nor have the public generally any conception of the lamentable condition of hundreds of the children, and the boys and girls at the East-end of London. It is simply fearful. Sunday-schools, Ragged-schools, and Bands of Hope confer great benefits upon many of them, but the majority are shamefully neglected by their parents. Let any one walk through Poplar, Spitalfields, Whitechapel, Commercial-Road, Ratcliff Highway, Aldgate, and Back Church-lane, I as I have done, and he will see scores of children who are not children, but little withered imps of cruelty, falsehood, and vice. He will also see elder boys and girls who are the victims of the most precocious passions—hard, foul, repulsive, and savage, who hate the parents who forsook them, the law that punishes them, and the Christians who would fain reclaim them. He will hear them coin oaths with horrible facility, see them drink gin like water, and, should they quarrel, he will witness such a fight as will make him expect a murder. The twin monsters of this vast district of the metropolis are Dirt and Drunkenness. King Dirt is everywhere. There is a fetid smell, a sickly atmosphere, which makes you feel faint and weary. Your lips grow clammy; your linen looks yellow; your hands get defiled: your eyes grow dim; you long for green fields, fresh air, flowers, and bright skies. But, alas! they are not near you, and if, perchance, you should pass some building with 'Ragged-school' over the door, and looking in see a number of poor, white, forlorn children, who, when the teacher says "Rise", stand up and sing — There is a happy land, Far far away, you pass on with tears in your eyes, for you feel, also, that the happy land is indeed far far away. King Drunkenness, however, reigns quite as much as King Dirt. There are thousands of sober men and women in the East of London, no doubt, and the Bands of Hope there will, it is anticipated, do much to produce a sober future; but any one who explores the localities infected with cholera, and also the contiguous parishes, will be shocked at the evident supremacy of drunkenness. Many men and women seem to drink apparently nearly every penny they can spare, and many which they cannot spare. Hence rags, desolate homes, crime, pauperism, and now pestilence in its most fatal form. I do not exaggerate the state of things. An agent of the London City Mission says:—There is perhaps more wickedness in Shadwell than in any other parish in London. As you walk through the streets the scenes of wickedness that meet your eyes, and the profane language that sounds upon your ears, cannot be described. If such wickedness is met with in the public streets, what is to be met with in public houses where men and women meet to practise wickedness, and to strive to excel each other in sin, and where that man is counted a king among men who can swear the loudest, and who is most fruitful in inventing fresh deeds of darkness? The seafaring part of the population are much addicted to intemperance, and this tends to produce many sanitary and social evils. A competent witness writes:—It is really lamentable to see the number of our English seamen who live more like the beasts that perish than men possessing immortal souls; and what is a disgrace to our country may be seen in our docks at all times when a ship is leaving for some foreign port, in the fact that our seamen seem as if they could not face the winds and the waves, nor take farewell of their native shores, but in a state of intoxication. The brave and noble captain of the ill-fated ship London said to me before leaving the docks on his last voyage, 'It is a great pity we cannot get our sailors to leave our ports in a sober state.' An intelligent missionary, who labours in the east, states that Millwall, Cubitttown, Blackwall, Poplar, The Orchard, and Poplar New Town, contain 200 public-houses. What wonder is it, then, that King Drunkenness reigns? The prevalence of cholera in these parts is, doubtless, increased by the prevalence of intemperate habits. Such habits are associated with late hours, unwashed bodies, filthy homes, predisposition to infection, improper food, heats and colds, debilitated constitutions, and a morbid fear of death—all of which tend to spread the pestilence. Thus, a woman whose brother resides in Scotland, wrote to him for help in the present distress, and he sent her some clothing. She took it to the pawnshop, thence she went to the public-house and got drunk. Both she and her daughter have died of cholera. Another hideous occurrence took place on Sunday last. The driver of a hearse on a 'cholera job' fell from his seat, and lay sprawling in the street, shouting, "Cholera, cholera!" He was drunk! What can be done to check this horrid vice? One thing might be done. Every publican who supplies liquor to drunken persons should be summoned before a magistrate and fined in the most severe manner. No publican who allows men to get drunk on his premises, or serves them when intoxicated, should be permitted by the police to do so. It is a social crime for any class to profit by drunkenness at such a crisis as this. Drunkenness breeds cholera as marshes breed fever. Dr. Sewall, who visited the cholera hospitals of New York, states that of 204 cases in Park Hospital, there were only six temperate persons. |

This article, 'The Haunts of the East End Anarchist', from the Evening Standard

of

2 October 1894, begins with a description of the area before turning to a lurid and

thoroughly racist account of the activities of the radical Jewish

groups that were meeting locally. See below for pictures of the streets mentioned.

|

Just beyond the Proof-house of the Gunmakers' Company near the Whitechapel end of the Commercial Road, begins a series of narrow streets running at right angles to the main thoroughfare, and cutting Fairclough Street at the further extremity, where the Tilbury and Southend Railway passes through the district [see below]. More or less alike in appearance, these byways, for they are no more, consist entirely of small two-storeyed tenements with an occasional stable or cow-shed to break the monotony, and a sprinkling of little shops devoted to coal and dried fish, stale fruit and potatoes, pickled cucumbers and salt herrings, shrivelled sausages and sour brown bread. There is Backchurch Lane, where the Irish resident still holds his own against the incoming Russo-Jewish settler, and Berner [now Henriques] Street, where the window bills, written in Hebrew characters. inform you that there are 'loshing' or a 'bek-rum' (back room) to let, and thus proclaim the nationality of its denizens. There is Batty Street wholly given over to the foreign tailors, clickers and 'machiners'; Christian Street, long since an appanage of East End Jewry, and Grove [now Golding] Street, where the low-pitched tenements are so far below the pavement level that the passer-by can comfortably shake hands with the residents off the top floor through the bedroom windows. And

intersecting all these are a number of courts, alleys, and passages, so

dark and narrow, so dirty and malodorous, that the purlieus of Seven

Dials and the backways of Clare Market may be called light and airy in

comparison with them. Some are blind, others lead through to the

adjoining thoroughfare. Some branch off to right and left, others

conduct one to open spaces forming irregular quadrangles lined with

houses below the street level, so small and snug that the occupier

standing in his front parlour can open the door, stir the fire, reach

the dustbin outside, or make the bed inside without stirring from the

spot. Courts and alleys, streets and yards, all are densely packed, in

many cases even to the cellars below lighted by small gratings in the

pavement. And the whole district, stretching from Backchurch Lane on

one side to Morgan Street on the other, is the resort and principal

abiding-place of the East End Anarchists. In the side streets and

alleys hereabouts the majority of them live and loaf; within a stone's

throw are their favourites haunts, the coffee-shops they patronise, and

the private gambling-clubs where many spend their evenings, and close

by is their printing press, their temporary club and meeting house, and

even the tavern where their Friday evening discussions take place. If

I dig in the mines of the frozen north,

I'll dig with a will: the ore I bring forth May yet make a knife - a knife for the throat of the Tsar. If I toil in the south, I'll plough and sow Good honest hemp; who knows, I may grow A rope - a rope for the neck of the Tsar. Sarah

Bernhardt might envy the fire and verve with which this recitation is

given by one of the Jewesses, and there can be no possible mistake

about the sentiments of the speaker and her auditory, whatever there

may be about the merits of the verses. And the same fiery stuff, or

fiery stuff of the same description, is being spouted about the same

time at half a dozen other branches of the Anarchist League in the

district between Backchurch Lane and the New Road, that runs up to

Whitechapel. Everything is turned to account, tool for the purposes of

its mischievous propaganda. Why, before the meeting is closed one

member produces and sings an Anarchist version of 'After the Ball',

with a finely-buttered moral drawn from the contrast between the

wealthy dancers inside and the shivering poor outside, winding up with

an Anglo-Yiddish chorus in which all join. |

On 28 June 1885 Miriam Angel was murdered at 16 Batty Street.

She was 21, from Warsaw, and lived with her husband Isaac and was six

months pregnant. When her mother called to visit and got no response,

she sent for the doctor, who found her dead with aquafortis (nitric acid) pouring

from her mouth, wounds to her head and evidence of rape. The attic lodger Israel Lipski (né Lobulsk), a Polish-Jewish 'stick-maker'

(umbrella frame maker) was found in her room, also with acid burns, but survived. He alleged that two fellow-workers, Harry Schmuss and Simon Rosenbloom, had

attacked them, demanding his gold chain, though they claimed to have a good

relationship with him. He had lived in the house for two

years, and was engaged to Kate Lyons, who protested his innocence. A

public subscription was taken up to pay for his defence, but the

barrister engaged, George Geoghegan, had a drink problem so in the

event it was a commercial lawyer who acted for Lipski. The evidence was

confused: a chemist from Bell & Co on the Commercial Road said that

a foreigner had bought acid a few days earlier and he could tell he

was a stick-maker from his clothes, yet it was also said that the

crime was not planned in advance; the rules at that time denied a

closing speech to the defence if the accused spoke for himself or

called witnesses, so Lipski kept silent; and the judge's summing up was

heavily weighted against him.

On 28 June 1885 Miriam Angel was murdered at 16 Batty Street.

She was 21, from Warsaw, and lived with her husband Isaac and was six

months pregnant. When her mother called to visit and got no response,

she sent for the doctor, who found her dead with aquafortis (nitric acid) pouring

from her mouth, wounds to her head and evidence of rape. The attic lodger Israel Lipski (né Lobulsk), a Polish-Jewish 'stick-maker'

(umbrella frame maker) was found in her room, also with acid burns, but survived. He alleged that two fellow-workers, Harry Schmuss and Simon Rosenbloom, had

attacked them, demanding his gold chain, though they claimed to have a good

relationship with him. He had lived in the house for two

years, and was engaged to Kate Lyons, who protested his innocence. A

public subscription was taken up to pay for his defence, but the

barrister engaged, George Geoghegan, had a drink problem so in the

event it was a commercial lawyer who acted for Lipski. The evidence was

confused: a chemist from Bell & Co on the Commercial Road said that

a foreigner had bought acid a few days earlier and he could tell he

was a stick-maker from his clothes, yet it was also said that the

crime was not planned in advance; the rules at that time denied a

closing speech to the defence if the accused spoke for himself or

called witnesses, so Lipski kept silent; and the judge's summing up was

heavily weighted against him.

He was convicted and sentenced to hang;

the night before his execution at Newgate he made a full 'confession'

to the Rev Simeon Singer (a rabbi who at the time of Queen Victoria's

jubilee asserted, of the Jewish population of London, we are Englishmen and and the thoughts and feelings of Englishmen are our thoughts and feelings); but the details of this confession didn't add up. A wave of antisemitism followed - 'Lipski' became a term of abuse. No.16 and the adjoining houses on Batty Street were demolished and rebuilt - right is the doorway to no.14, and views of Batty Street in 2000, and two today, looking south towards St George's Estate. See further Martin L. Friendland The Trails of Israel Lipski (Beaufort 1985).

He was convicted and sentenced to hang;

the night before his execution at Newgate he made a full 'confession'

to the Rev Simeon Singer (a rabbi who at the time of Queen Victoria's

jubilee asserted, of the Jewish population of London, we are Englishmen and and the thoughts and feelings of Englishmen are our thoughts and feelings); but the details of this confession didn't add up. A wave of antisemitism followed - 'Lipski' became a term of abuse. No.16 and the adjoining houses on Batty Street were demolished and rebuilt - right is the doorway to no.14, and views of Batty Street in 2000, and two today, looking south towards St George's Estate. See further Martin L. Friendland The Trails of Israel Lipski (Beaufort 1985).

Right are some 1909 images of the area: (1) Berner [now Henriques] Street - with Nelson

Beer House on the corner (no.46); by the cartwheel is the entrance to

Dutfield's Yard where the body of Elizabeth Stride was found in 1888; (2) no.31; (3) Fairclough Street

[named for the Fairclough family in 1869 - previously North Street] from the corner of Berner Street; (4) 1-15 Fairclough Street.

Right are some 1909 images of the area: (1) Berner [now Henriques] Street - with Nelson

Beer House on the corner (no.46); by the cartwheel is the entrance to

Dutfield's Yard where the body of Elizabeth Stride was found in 1888; (2) no.31; (3) Fairclough Street

[named for the Fairclough family in 1869 - previously North Street] from the corner of Berner Street; (4) 1-15 Fairclough Street.

Left are three street corners in 1938: (1) Fairclough and Brunswick Streets (2) Christian and Ellen Streets; (3) Fairclough & Christian Streets, the Beehive public house where in 1888 Diemschütz and

Kozebrodski went for help on finding Elizabeth Stride's body - now the site of Harkness House.

Left are three street corners in 1938: (1) Fairclough and Brunswick Streets (2) Christian and Ellen Streets; (3) Fairclough & Christian Streets, the Beehive public house where in 1888 Diemschütz and

Kozebrodski went for help on finding Elizabeth Stride's body - now the site of Harkness House.

POTTER AND CLARKE, FAIRCLOUGH STREET

POTTER AND CLARKE, FAIRCLOUGH STREET

In 1925 they built a new drug grinding plant on Fairclough Street (on

the site of Oates Drug Mills) on Berner

[Henriques] Street, designed in 1923 by Wheat and Luker, and now

apartments [right, together with Fairclough Street today]. The Industrial Chemist of 1932 (vol 8, page 9) reported this factory is an entirely self-contained

one and has its own water supply from two artesian wells, one of

which is at present in operation and giving 4,500 gallons per hour,

which is automatically pumped to tanks on the roof. Left is a new gate to Victoria Yard, and the factory, now apartments, adjacent to two remaining 19th century buildings (nos. 8 & 10).

In 1925 they built a new drug grinding plant on Fairclough Street (on

the site of Oates Drug Mills) on Berner

[Henriques] Street, designed in 1923 by Wheat and Luker, and now

apartments [right, together with Fairclough Street today]. The Industrial Chemist of 1932 (vol 8, page 9) reported this factory is an entirely self-contained

one and has its own water supply from two artesian wells, one of

which is at present in operation and giving 4,500 gallons per hour,

which is automatically pumped to tanks on the roof. Left is a new gate to Victoria Yard, and the factory, now apartments, adjacent to two remaining 19th century buildings (nos. 8 & 10).  had occupied the adjacent premises at Victoria Steam Mills [left on Goad's 1899 insurance map]. Herbert Henry

Gates was in partnership with George Hewett until 1892, and then until

1895 with Charles Murray Hornibrook as Drug, Grist and Spice

Grinders and also Mica, Coal Dust, Charcoal, Plumbago, and Fuller's Earth

Merchants and Grinders at Victoria Steam Mills, Fairclough St, when

Hornibrook continued the business (living at 105a Haverstock Hill in Hampstead.

had occupied the adjacent premises at Victoria Steam Mills [left on Goad's 1899 insurance map]. Herbert Henry

Gates was in partnership with George Hewett until 1892, and then until

1895 with Charles Murray Hornibrook as Drug, Grist and Spice

Grinders and also Mica, Coal Dust, Charcoal, Plumbago, and Fuller's Earth

Merchants and Grinders at Victoria Steam Mills, Fairclough St, when

Hornibrook continued the business (living at 105a Haverstock Hill in Hampstead. He was an amateur poet, perhaps involved in amateur dramatics, publishing

between 1908-11 various Lyrics, including some 'for private circulation to composers and editors' and others 'for musical comedy,

pantomime, or variety numbers', Redruth, a collection of verses entitled simply High, and The Telegraphic Kiss - a notion which appears to date from an 1887 poem by Mary Ella Tilltson which ends with the words Full oft I think of thee, at morn and dewy even; / When mind is soaring

free, and when to task 'tis given. / As science news transmits by air's

electric fires, / Souls telegraphic kiss on viewless spirit wires. Right is a contemporary postcard illustrating this curious concept.

He was an amateur poet, perhaps involved in amateur dramatics, publishing

between 1908-11 various Lyrics, including some 'for private circulation to composers and editors' and others 'for musical comedy,

pantomime, or variety numbers', Redruth, a collection of verses entitled simply High, and The Telegraphic Kiss - a notion which appears to date from an 1887 poem by Mary Ella Tilltson which ends with the words Full oft I think of thee, at morn and dewy even; / When mind is soaring

free, and when to task 'tis given. / As science news transmits by air's

electric fires, / Souls telegraphic kiss on viewless spirit wires. Right is a contemporary postcard illustrating this curious concept. | Fleecy white clouds across a sky of

blue, Bright golden sunshine piercing white clouds through. The fragrant mem'ry lingers with me yet, When our lips shared that Salvo cigarette. |

Fancy white paper, curling smokes of

blue, Bright cold toboacco, piercing paper through, Aroma fragrant lingers with me yet, When our lips shared that Salvo cigarette. |

How does the fragrance of the Salvo

cigarette compare with the American dollar?

Because therein a hundred scents lie hid. (Told to the Marine): |

William

Meredith founded a bakery in 1830, with William Drew as his principal

assistant. After a quarrel Drew set up a rival firm in High Street

Shadwell: both prospered. In 1871 Henry Anthony Meredith left the

partnership with William Frederick and George, then established at 58

Christian Street as steam biscuit makers. By 1890 these premises were inadequate, and the Shadwell firm too much

for one man; so the founders' sons Frederick Meredith and Lear J. Drew

put their quarrel aside and merged as Meredith & Drew

(the agreement was endorsed in 1891, the order of their names decided by

the toss of a coin). In 1892 they had an office at 181 Queen Victoria

Street, and in 1896 they took on the business and premises of Francis

Lemann at Field Place, St John's Street Clerkenwell and 28-29 St

Swithuns Lane in the City, for £2500. They made crisps and biscuits,

including one 'for cyclists' [right].

Goad's map of 1899 showed the Christian Street premises as stables,

but with a series of bakers' ovens, across the road, between Christian

and Brunswick Streets, in basements and under the street.

William

Meredith founded a bakery in 1830, with William Drew as his principal

assistant. After a quarrel Drew set up a rival firm in High Street

Shadwell: both prospered. In 1871 Henry Anthony Meredith left the

partnership with William Frederick and George, then established at 58

Christian Street as steam biscuit makers. By 1890 these premises were inadequate, and the Shadwell firm too much

for one man; so the founders' sons Frederick Meredith and Lear J. Drew

put their quarrel aside and merged as Meredith & Drew

(the agreement was endorsed in 1891, the order of their names decided by

the toss of a coin). In 1892 they had an office at 181 Queen Victoria

Street, and in 1896 they took on the business and premises of Francis

Lemann at Field Place, St John's Street Clerkenwell and 28-29 St

Swithuns Lane in the City, for £2500. They made crisps and biscuits,

including one 'for cyclists' [right].

Goad's map of 1899 showed the Christian Street premises as stables,

but with a series of bakers' ovens, across the road, between Christian

and Brunswick Streets, in basements and under the street.

In 1905 Meredith & Drew merged with the small firm of Wright & Son

which had established itself selling tins of biscuits, and

also a cheddar sandwich biscuit - 'a meal for a penny'. The 'son' of

the title was T.R. Wright, who had a sharp marketing mind. In the

Jewish East End, shops sold out before Passover. One Passover, as soon

as the sun had set marking its conclusion, Wright sent his vans around

the

area; one traveller alone sold £300 of goods, and next day their

competitors found all the shops fully stocked. After the merger Wright & Son remained

as a

subsidiary to preserve goodwill, and Wright became a dynamic managing

director.

In 1905 Meredith & Drew merged with the small firm of Wright & Son

which had established itself selling tins of biscuits, and

also a cheddar sandwich biscuit - 'a meal for a penny'. The 'son' of

the title was T.R. Wright, who had a sharp marketing mind. In the

Jewish East End, shops sold out before Passover. One Passover, as soon

as the sun had set marking its conclusion, Wright sent his vans around

the

area; one traveller alone sold £300 of goods, and next day their

competitors found all the shops fully stocked. After the merger Wright & Son remained

as a

subsidiary to preserve goodwill, and Wright became a dynamic managing

director.

As

it continued to grow, the firm continued to produce a single product in

each plant, and this was to prove a strength. Left is a wartime distribution of biscuits in the East End. Their head office moved to

Ashby-de-la-Zouch in Leicestershire. Right are some advertisements from the 1950s. In 1967 it became part of United

Biscuits and part of the UB KP division, together with Kenyon Sons

& Craven Ltd, nut processors since 1891.

As

it continued to grow, the firm continued to produce a single product in

each plant, and this was to prove a strength. Left is a wartime distribution of biscuits in the East End. Their head office moved to

Ashby-de-la-Zouch in Leicestershire. Right are some advertisements from the 1950s. In 1967 it became part of United

Biscuits and part of the UB KP division, together with Kenyon Sons

& Craven Ltd, nut processors since 1891.

had an engineering works at 44 Christian Street (Goad's 1899 insurance map, left, shows their premises, between Christian and Grove Street, noting two areas where patterns were stored), and also traded from

67 Lord Street in Liverpool. His son Frank Walter Scott, who

had been articled to a German firm and then ran his father's drawing

office, designed and constructed a gas-compressing plant plant at the

Royal Institution and developed various items of hydraulic machinery

[example right]; he was an

Associate Member of the Institution of Civil Engineers. His brother

Frederick, of 94 Cannon Street Road, was a 'county engineer'. In 1896 Frank Walter Scott the younger withdrew from the partnership with Frank Walter the elder and Ernest

George. The Chemical Trade Journal & Chemical Engineer of 1920 reported that In the recovery of volatile solvents,

H. J. Pooley and G. Scott and Son have patented apparatus

whereby the whole of the air or gas in a heated drying chamber is

circulated rapidly by a large fan and a small proportion is continuously

removed by a small fan,

passed through a recovery plant, reheated, and returned to the

chamber. Heat is conveniently applied to the air or gas at a point in

the suction pipe of the large fan. In 1923 a patent was granted to G. Scott & Son (London) Ltd

and H.J. Pooley for apparatus for drying and impregnating insulated

electrical cables, and in 1933 (with G.W. Riley) for vacuum distillation of high-boiling products.

had an engineering works at 44 Christian Street (Goad's 1899 insurance map, left, shows their premises, between Christian and Grove Street, noting two areas where patterns were stored), and also traded from

67 Lord Street in Liverpool. His son Frank Walter Scott, who

had been articled to a German firm and then ran his father's drawing

office, designed and constructed a gas-compressing plant plant at the

Royal Institution and developed various items of hydraulic machinery

[example right]; he was an

Associate Member of the Institution of Civil Engineers. His brother

Frederick, of 94 Cannon Street Road, was a 'county engineer'. In 1896 Frank Walter Scott the younger withdrew from the partnership with Frank Walter the elder and Ernest

George. The Chemical Trade Journal & Chemical Engineer of 1920 reported that In the recovery of volatile solvents,

H. J. Pooley and G. Scott and Son have patented apparatus

whereby the whole of the air or gas in a heated drying chamber is

circulated rapidly by a large fan and a small proportion is continuously

removed by a small fan,

passed through a recovery plant, reheated, and returned to the

chamber. Heat is conveniently applied to the air or gas at a point in

the suction pipe of the large fan. In 1923 a patent was granted to G. Scott & Son (London) Ltd

and H.J. Pooley for apparatus for drying and impregnating insulated

electrical cables, and in 1933 (with G.W. Riley) for vacuum distillation of high-boiling products.

South of Boyd and Ellen

Streets (which remain) up to the railway viaduct were narrow back streets: Mary Ann, Servern(e), Splidts [formerly Terrace], Elizabeth [now Stutfield] and Phil(l)ip [renamed Philchurch Street, of which Philchurch Place is a reminder], and courts such as Prince of Orange Court. Henry and Everard

Street were to the north. Along Mary Ann and Philchurch Street were the

small late Victorian blocks Ruth Mansions, Beatrice House, Elsie House,

Doris House and Lilian House [left before

demolition in 1975]. They housed various waves of immigrants, some

of whom became naturalised (eg Wladyslaw Zuarawski, a marine engineer

from Poland in 1955, and Mohamed Jamah Dualeh and Mahamoud Mohamed Ali,

from 'Somaliland' in 1972) or changed their names (eg Issy Hescovitch

to Sidney Hurst, Joseph Rabinovitch to Richard Joseph Rayner,

and (British-born) Jenny Waitkakis to Jean Kearney all in 1941, and

Abraham Schlazer to Alfred Slater in 1943). Bloomah Eva (Evelyn)

Eisenberg, born in Ellen House, Splidts Street, married Benjamin

Blacker, a tailor in 1937 at Jubilee Street Great Syngagogue; they

lived in Lilian House until they emigrated to California. There was a synagogue on Philip Street. Beatrice Ali, in The Good Deeds of a Good Woman (Dobson 1976) describes her mixed-race marriage to a sailor, and life in Elsie House, where the rent was 10s. 8d. a week. Right - 25 Philchurch Street before demolition.

South of Boyd and Ellen

Streets (which remain) up to the railway viaduct were narrow back streets: Mary Ann, Servern(e), Splidts [formerly Terrace], Elizabeth [now Stutfield] and Phil(l)ip [renamed Philchurch Street, of which Philchurch Place is a reminder], and courts such as Prince of Orange Court. Henry and Everard

Street were to the north. Along Mary Ann and Philchurch Street were the

small late Victorian blocks Ruth Mansions, Beatrice House, Elsie House,

Doris House and Lilian House [left before

demolition in 1975]. They housed various waves of immigrants, some

of whom became naturalised (eg Wladyslaw Zuarawski, a marine engineer

from Poland in 1955, and Mohamed Jamah Dualeh and Mahamoud Mohamed Ali,

from 'Somaliland' in 1972) or changed their names (eg Issy Hescovitch

to Sidney Hurst, Joseph Rabinovitch to Richard Joseph Rayner,

and (British-born) Jenny Waitkakis to Jean Kearney all in 1941, and

Abraham Schlazer to Alfred Slater in 1943). Bloomah Eva (Evelyn)

Eisenberg, born in Ellen House, Splidts Street, married Benjamin

Blacker, a tailor in 1937 at Jubilee Street Great Syngagogue; they

lived in Lilian House until they emigrated to California. There was a synagogue on Philip Street. Beatrice Ali, in The Good Deeds of a Good Woman (Dobson 1976) describes her mixed-race marriage to a sailor, and life in Elsie House, where the rent was 10s. 8d. a week. Right - 25 Philchurch Street before demolition.

The area was redeveloped by the London County Council before and after

World War II as the

Berner Estate. Everard House, 1934-36, between Boyd and Ellen Streets

is a long five-storey range, with access balconies and 'streamlined'

corners; the top floor laundry rooms became additional flats in the

1950s [left - rear in 1938, and front and rear today].

The area was redeveloped by the London County Council before and after

World War II as the

Berner Estate. Everard House, 1934-36, between Boyd and Ellen Streets

is a long five-storey range, with access balconies and 'streamlined'

corners; the top floor laundry rooms became additional flats in the

1950s [left - rear in 1938, and front and rear today].

Batson House [right] is similar, as is the post-war Hanson House on Pinchin

Street. Hadfield, Kindersley and

Langmore Houses form a U-shaped composition, begun in 1949 and

refurbished in the 1990s. East of Stutfield Street is Halliday House,

of 1961-62, an 8-storey block with corner balconies.Also right are the later Bicknell House (Ellen Street) and Harkness House.

Batson House [right] is similar, as is the post-war Hanson House on Pinchin

Street. Hadfield, Kindersley and

Langmore Houses form a U-shaped composition, begun in 1949 and

refurbished in the 1990s. East of Stutfield Street is Halliday House,

of 1961-62, an 8-storey block with corner balconies.Also right are the later Bicknell House (Ellen Street) and Harkness House.

Philchurch

Place now houses Wapping Women's Centre, established in 1981 to empower

women of the Bangladeshi community. It runs a childcare centre

(Playzone), breakfast and luncheon clubs, and arts projects; but most

significantly, under the leadership of Sufia Alam,

a community garden established in 1999 in a derelict and verminous

space between three of the housing blocks, where women (with discreet

support from their men!) now grow vegetables, herbs and flowers; the 26

plots are carefully managed and allocated to residents, who swap seeds,

are 'eco-champions', and hold an annual competition with prizes for the

largest vegetables, on the lines of a traditional village fete, and

participate in the Healthy Chula programme.

Philchurch

Place now houses Wapping Women's Centre, established in 1981 to empower

women of the Bangladeshi community. It runs a childcare centre

(Playzone), breakfast and luncheon clubs, and arts projects; but most

significantly, under the leadership of Sufia Alam,

a community garden established in 1999 in a derelict and verminous

space between three of the housing blocks, where women (with discreet

support from their men!) now grow vegetables, herbs and flowers; the 26

plots are carefully managed and allocated to residents, who swap seeds,

are 'eco-champions', and hold an annual competition with prizes for the

largest vegetables, on the lines of a traditional village fete, and

participate in the Healthy Chula programme.

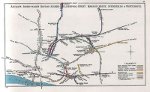

Pinchin

Street (formerly Thomas Street, presumably renamed named for Pinchin & Johnson, below) runs alongside the railway viadact which led north from the main

line to the London, Tilbury & Southend Railway's goods depot on

Commercial Road, opened in 1886, one of several short spurs to goods

stations and depots in the area [map right]. At

the same time, a hydraulic pumping station to power the equipment

shifting wagons to and from street level was built in nearby Hooper Street -

see here for details.

The street's main claim to fame is as a 'Ripper site'. On 10 September

1889 a headless female torso, possibly that of Linda Hart, a local

prostitute, was found under one of the railway arches - many sites

refer!

Pinchin

Street (formerly Thomas Street, presumably renamed named for Pinchin & Johnson, below) runs alongside the railway viadact which led north from the main

line to the London, Tilbury & Southend Railway's goods depot on

Commercial Road, opened in 1886, one of several short spurs to goods

stations and depots in the area [map right]. At

the same time, a hydraulic pumping station to power the equipment

shifting wagons to and from street level was built in nearby Hooper Street -

see here for details.

The street's main claim to fame is as a 'Ripper site'. On 10 September

1889 a headless female torso, possibly that of Linda Hart, a local

prostitute, was found under one of the railway arches - many sites

refer!

Hard up against the viaduct was Frederick Street, long gone. The goods depot closed in 1967 and most of the viaduct was demolished, leaving a short spur which campaigners have fought to save as a nature space [left],

a space housing local businesses in the arches, and to prevent further

local overcrowding. Here are various views of the street, including

arch no.15 some years ago where a 'traditional' craft was practised. Among current businesses 'under the arches' is the Hand & Eye Press, started in 1985 at no.6 and using traditional letterpress technology; far right shows the space typically in one of the units.

Hard up against the viaduct was Frederick Street, long gone. The goods depot closed in 1967 and most of the viaduct was demolished, leaving a short spur which campaigners have fought to save as a nature space [left],

a space housing local businesses in the arches, and to prevent further

local overcrowding. Here are various views of the street, including

arch no.15 some years ago where a 'traditional' craft was practised. Among current businesses 'under the arches' is the Hand & Eye Press, started in 1985 at no.6 and using traditional letterpress technology; far right shows the space typically in one of the units.

At the eastern end of Pinchin Street, beyond the arches, are two interesting buildings - one old, one new. At no.2 [left, 3 views] on the corner with Christian Street - formerly the site of a pub, the Blacksmith Arms - is the Pinchin Street Studios and Group Practice, constructed in 2007 by Urban Space Management Ltd

from 35 shipping containers to provide ten units: a doctors' surgery

on the first two floors, office space on the next three, and with a

roof garden and plant nursery with spectacular views. Sadly, it is currently vacant. (See here for another similar building.) Next door [right, two views], at no.4

is the former warehouse (now flats) of Pinchin and Johnson,

a paint company selling oils and turpentines started in 1834 in

Silvertown. They opened branches around the world, and were listed on

the original FT 30 index. In 1960 it was bought by Courtaulds who

merged it with International Paints in 1968. ('L' prefix codes for

nitro-cellulose car paints refer to their products.) Opposite is a mosque, the East London Markazi Masjid.

At the eastern end of Pinchin Street, beyond the arches, are two interesting buildings - one old, one new. At no.2 [left, 3 views] on the corner with Christian Street - formerly the site of a pub, the Blacksmith Arms - is the Pinchin Street Studios and Group Practice, constructed in 2007 by Urban Space Management Ltd

from 35 shipping containers to provide ten units: a doctors' surgery

on the first two floors, office space on the next three, and with a

roof garden and plant nursery with spectacular views. Sadly, it is currently vacant. (See here for another similar building.) Next door [right, two views], at no.4

is the former warehouse (now flats) of Pinchin and Johnson,

a paint company selling oils and turpentines started in 1834 in

Silvertown. They opened branches around the world, and were listed on

the original FT 30 index. In 1960 it was bought by Courtaulds who

merged it with International Paints in 1968. ('L' prefix codes for

nitro-cellulose car paints refer to their products.) Opposite is a mosque, the East London Markazi Masjid.