Jewish Presence (1) -

Settlement

note:

the Whitechapel Gallery, a fine Arts & Crafts building of 1901 designed by Charles Harrison Townsend, restored and extended in 2009, became a

focal point for Jewish intellectual life in the area ('the University of the Ghetto'), and its reading

room and exhibitions reflect this, as does Bernard Kops' poem Whitechapel Library, Aldgate East. Our local First World War poet Isaac Rosenberg is commemorated here with a blue plaque.The London Metropolitan Archives has

a good display of Jewish life in the East End, based around a wall-size

version of the map shown below.

note:

the Whitechapel Gallery, a fine Arts & Crafts building of 1901 designed by Charles Harrison Townsend, restored and extended in 2009, became a

focal point for Jewish intellectual life in the area ('the University of the Ghetto'), and its reading

room and exhibitions reflect this, as does Bernard Kops' poem Whitechapel Library, Aldgate East. Our local First World War poet Isaac Rosenberg is commemorated here with a blue plaque.The London Metropolitan Archives has

a good display of Jewish life in the East End, based around a wall-size

version of the map shown below.

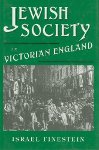

(Judge) Israel Finestein Jewish Society in Victorian England: Collected Essays (Vallentine Mitchell 1993) provides valuable background material. See also a brief article The Life and Legacy of the Jewish East End (Public Spirit 2014) by Leon Silver, President of the East London Central Synagogue and a key member of Tower Hamlets Inter Faith Forum.

See here for the 1983 Auschwitz exhibition at St George-in-the-East.

A

new immigrant community

In Russia, Tsar Nicholas I (1825-55) issued many decrees regulating

Jewish life, and after the collapse of Poland in 1835 Jews were mainly

confined to the Pale of

Settlements (present-day Lithuania,

Ukraine, Belarus and eastern Poland), where they lived in isolated and

impoverished shtetls (small market towns). The assassination of Tsar

Alexander II in 1881 led to vicious pogroms (the worst at Kishinev in

1903), and vast numbers fled. Many of them walked

to Hamburg, from where - if they could obtain a visa, which usually

involved bribery - they could sail to London in appalling

steerage

class conditions

for 16s. a head (half price for children). From 1880-1895 they landed

at Irongate Steps, Tilbury Dock, where some were sold bogus onward

tickets to the USA.

There

were 6,000 Jews in England in 1740, 20,000 in 1810, 35,000 in 1850 and

60,000 in 1880; by 1914 this had increased to 300,000 (official figures

almost certainly under-represent the

numbers, because of the immigants' fear that overcrowding would be reported). The

majority were in London. Previous Jewish settlers -

mainly Spanish and Portuguese, and Dutch Ashkenazis - were horrified at

the influx: in 1888 the former Chief Rabbi Nathan Adler wrote to the

rabbis in Eastern Europe: Every

Rabbi of a community kindly to preach

in the synagogue and house of study, to publicise the evil which is

befalling our brethren who have come here and to warn them not to come

to the land of Britain, for such ascent is descent.

Reports home from

families who had settled here were garbled and contradictory.

G. Eugene

Harfield's handsomely-printed Commercial

Directory of the Jews of the United Kingdom (Hewlett

& Pierce 5634/1894), listing established traders and professionals

(including barristers) throughout the land, is a sign of the desire to

make good by assimilation, which a flood of poor immigrants threatened

- see below. Significantly, its title page [right] combines Palestinian

aspirations and loyalty to the Crown. (See here

for the listings of shops and businesses in this parish.) By

contrast, many

eastern European immigrants espoused radical politics: see here for

a scurrilous, and racist, article from the Evening Standard of

1894 on the 'haunts of the anarchists'.

G. Eugene

Harfield's handsomely-printed Commercial

Directory of the Jews of the United Kingdom (Hewlett

& Pierce 5634/1894), listing established traders and professionals

(including barristers) throughout the land, is a sign of the desire to

make good by assimilation, which a flood of poor immigrants threatened

- see below. Significantly, its title page [right] combines Palestinian

aspirations and loyalty to the Crown. (See here

for the listings of shops and businesses in this parish.) By

contrast, many

eastern European immigrants espoused radical politics: see here for

a scurrilous, and racist, article from the Evening Standard of

1894 on the 'haunts of the anarchists'.

The British Brothers

League, formed in 1901, agitated for an end to

immigration and called for repatriation. Who is corrupting our morals?

The Jews. Who is destroying our Sundays? The Jews. Who is debasing our

national life? The Jews. Shame on them. Wipe them out.

Less extreme voices also called for restrictions, on health and housing

grounds, and these were explored by a 1903 Royal Commission on Alien

Immigration (see here for one example of evidence taken), resulting in the

1905 Aliens

Act, which had the effect of reducing

immigration by 40%. Immigration officers were given the

right to deport 'undersirable' (the term was not defined) immigrants. A

few Jewish politicians actually supported this trend, fearful for the

impact on what the community had so far achieved. It certainly

changed the scene: for instance, most Jewish schoolchildren were now

those of the second generation, who had been born here. The local Board

schools were heavily used for voluntary activities on Sundays.

Patterns of settlement

Russell & Lewis's 1900 map of Jewish East London [right] shows the density of Jewish settlement street by

street - from dark blue (over 95%) to dark pink (less than 5%). In this

parish, the dark blue areas were all north of the railway line: from

west to east, the Goodman's Fields area (then part of St Mark

Whitechapel), some streets to the east of Backchurch Lane (then part of

St John's parish), the area round Rampart Street, and the top of Watney

Street (then part of Christ Church parish). South of the railway, only

Cannon Street Road and Cable Street were predominantly Jewish, plus the

area north of the railway and west of Cannon Street Road. All other parts

of the parish are light or dark pink - including a few patches in the

Jewish 'heartlands': some of these were predominantly Irish.

Russell & Lewis's 1900 map of Jewish East London [right] shows the density of Jewish settlement street by

street - from dark blue (over 95%) to dark pink (less than 5%). In this

parish, the dark blue areas were all north of the railway line: from

west to east, the Goodman's Fields area (then part of St Mark

Whitechapel), some streets to the east of Backchurch Lane (then part of

St John's parish), the area round Rampart Street, and the top of Watney

Street (then part of Christ Church parish). South of the railway, only

Cannon Street Road and Cable Street were predominantly Jewish, plus the

area north of the railway and west of Cannon Street Road. All other parts

of the parish are light or dark pink - including a few patches in the

Jewish 'heartlands': some of these were predominantly Irish.

The details changed somewhat in the following years, but the pattern remained broadly the same.

Charles Booth's 1889/1898 poverty survey had noted The

German Jew is coming into St George's in large and increasing numbers.

They can live under conditions and so close together as to put to shame

the ordinary overcrowding of the English casual labourer ... There were

at one time only Irish colonies in St George's but these are slowly

giving way before the German Jew who ocupies their quarters and

supplants them in other ways. His secretaries saw their influence as mixed: although they contributed to appalling overcrowding, they presented a favourable contrast to the promiscuity of many of the English poor and could be seen as as cleaners or scavengers of districts of Irish poor, although this was not true in 'better' districts. See here for a sample local survey, and here for his listing of all the tailors working in the parish - predominantly Jewish, but some Irish - and here

for his more extended comments, published in 1902, combining concern

about the impact of Jewish settlement on the East End with a degree of

respect for their way of life and philanthropic arrangements.

Before

1939 there were some 80,000 Jews in the East End

and about 70 synagogues. However, although most homes were 'observant'

- keeping Sabbath and some or all of the dietary laws - synagogue

attendance was probably not more than 25% in most areas. The

institutions that promoted assimilation, education and career

aspiration were victims of their own success, with many of the

community prospering, moving on and 'marrying out'. Today it is

estimated that there are between two and three thousand Jews in the

'traditional' East End. There is not

a single kosher butcher (though plenty of halal ones), and the three

surviving synagogues struggle to

maintain a minyan (quorum of ten men) for the Shabbat service; others

have disappeared, often without a trace. But the Stepney Jewish Day

Centre (run by Jewish Care)

hosts about 700 people a week, and provides kosher meals on wheels.

There is a Jewish Society at Queen Mary College. And there are a few

remaining food shops, including Carmel Wines on the Mile End Road

(strictly kosher), some non-Beth Din bakers selling traditional bagels,

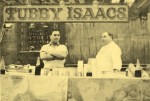

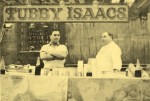

and Tubby Isaac's famous jellied eel stall remains near Aldgate East

station [right, then and now]: a commodity once common to all East Enders, which fell out of favour, but has recently become trendy.

Before

1939 there were some 80,000 Jews in the East End

and about 70 synagogues. However, although most homes were 'observant'

- keeping Sabbath and some or all of the dietary laws - synagogue

attendance was probably not more than 25% in most areas. The

institutions that promoted assimilation, education and career

aspiration were victims of their own success, with many of the

community prospering, moving on and 'marrying out'. Today it is

estimated that there are between two and three thousand Jews in the

'traditional' East End. There is not

a single kosher butcher (though plenty of halal ones), and the three

surviving synagogues struggle to

maintain a minyan (quorum of ten men) for the Shabbat service; others

have disappeared, often without a trace. But the Stepney Jewish Day

Centre (run by Jewish Care)

hosts about 700 people a week, and provides kosher meals on wheels.

There is a Jewish Society at Queen Mary College. And there are a few

remaining food shops, including Carmel Wines on the Mile End Road

(strictly kosher), some non-Beth Din bakers selling traditional bagels,

and Tubby Isaac's famous jellied eel stall remains near Aldgate East

station [right, then and now]: a commodity once common to all East Enders, which fell out of favour, but has recently become trendy.

Welfare agencies and housing initiatives

Various

welfare charities had been active in the first half of the 19th century to

cater for poor Jews in East London. Among those in this parish, see here for the Joel Emanuel Almshouse and the Hand in Hand Home which were based in Wellclose Square in the 1850s, and here

for the Jews' Orphan Asylum based in North Tenter Street from 1848-77,

and other Jewish influences in the Goodman's Field area. But with the

new influx in the latter years of the century, Baron Rothschild warned: We

have now a new Poland on our hands in East

London. Our first business is to humanise our Jewish immigrants and

then to Anglicise them.

(Basil Henriques later took the same approach.)

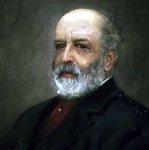

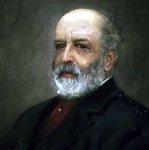

Lord Rothschild

(Nathaniel 'Natty' Mayer Rothschild) [right], head of the family bank after his

father's death in 1879, and the first (observant) Jewish peer (voting

with the Conservative and Unionists) was a key founder of the Four Per Cent Industrial Dwellings Company following the United Synagogue's 1884 enquiry into

'spiritual destitution'. Most of the patrons and tenants of their

'model artisan dwellings' were Jewish, particularly at the

Rothschild Buildings in Flower and Dean Street, which became a focal

point of Jewish life - see Jerry White Rothschild

Buildings: Life in an East End Tenement Block, 1887-1920 (Routledge

1980). (The company later built Albert Buildings

next to the Peabody Estate.) Notably, until his death in 1915, Lord Rothschild

was a trustee of the London Mosque Fund - a rôle later held by Lord Winterton.

Lord Rothschild

(Nathaniel 'Natty' Mayer Rothschild) [right], head of the family bank after his

father's death in 1879, and the first (observant) Jewish peer (voting

with the Conservative and Unionists) was a key founder of the Four Per Cent Industrial Dwellings Company following the United Synagogue's 1884 enquiry into

'spiritual destitution'. Most of the patrons and tenants of their

'model artisan dwellings' were Jewish, particularly at the

Rothschild Buildings in Flower and Dean Street, which became a focal

point of Jewish life - see Jerry White Rothschild

Buildings: Life in an East End Tenement Block, 1887-1920 (Routledge

1980). (The company later built Albert Buildings

next to the Peabody Estate.) Notably, until his death in 1915, Lord Rothschild

was a trustee of the London Mosque Fund - a rôle later held by Lord Winterton.

[Poor] Jews' Temporary Shelter

In 1885 a baker Simon Cohen, aka Becker, began to provide

temporary shelter at his premises in Church Lane, Whitechapel, but the

Board of Guardians closed it down: as the Jewish Chronicle reported, Its

abject misery is worse than any workhouse and it provides less food.

There is absolutely no sleeping accommodation except a wooden floor.

The only kind of daily food is rice and tea and bread and this is very

irregular. Let us get a ‘responsible committee’ or let a few gentlemen

see if they cannot get a few cheap mattresses for the older men to lie

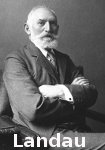

upon at night and some blankets or rugs. Hermann Landau [right, and pictured welcoming immigrants at the Shelter], a

banker who had come from Poland in 1864 and had become an influential

member of the Jewish community, rose to the challenge, with a couple of

others (and, in the early years, some Rothschild funding), and in 1886

the Jews' Temporary Shelter was established at 84 Leman Street [left] as an institution

in which newcomers, having a little money, might obtain accommodation

and the necessaries they required at cost price, and where they would

receive useful advice. (It's said that its address was traded across eastern Europe to aspiring emigrants.) Those with some resources were referred

to local lodging houses, where they were soon propositioned by

furniture contractors and landlords; those without were

referred to the Soup Kitchen for the Jewish Poor and other charitable

bodies. In 1895 it received substantial

funding from another banker-philanthropist, Samuel Montagu [right], who became a Liberal MP and later a peer.

In 1885 a baker Simon Cohen, aka Becker, began to provide

temporary shelter at his premises in Church Lane, Whitechapel, but the

Board of Guardians closed it down: as the Jewish Chronicle reported, Its

abject misery is worse than any workhouse and it provides less food.

There is absolutely no sleeping accommodation except a wooden floor.

The only kind of daily food is rice and tea and bread and this is very

irregular. Let us get a ‘responsible committee’ or let a few gentlemen

see if they cannot get a few cheap mattresses for the older men to lie

upon at night and some blankets or rugs. Hermann Landau [right, and pictured welcoming immigrants at the Shelter], a

banker who had come from Poland in 1864 and had become an influential

member of the Jewish community, rose to the challenge, with a couple of

others (and, in the early years, some Rothschild funding), and in 1886

the Jews' Temporary Shelter was established at 84 Leman Street [left] as an institution

in which newcomers, having a little money, might obtain accommodation

and the necessaries they required at cost price, and where they would

receive useful advice. (It's said that its address was traded across eastern Europe to aspiring emigrants.) Those with some resources were referred

to local lodging houses, where they were soon propositioned by

furniture contractors and landlords; those without were

referred to the Soup Kitchen for the Jewish Poor and other charitable

bodies. In 1895 it received substantial

funding from another banker-philanthropist, Samuel Montagu [right], who became a Liberal MP and later a peer.

Early annual reports on the Shelter's work were defensive: most

immigrants were healthy and had good work skills, they said; the

accommodation was deliberately basic and temporary, and supported by

weekly subscriptions from other settlers; and by providing protection

against exploitation by the dockside 'crimpers' they enabled those who

wished to

move on, particularly to the USA or South Africa, to do so, with the

help of other welfare agencies which quickly developed the skills to enable this. By 1890 numbers had increased by 50%, but many

of these achieved 'transmigration' - or even a return home. Indeed, in

the coming decade the shelter negotiated agencies with shipping lines

(especially the Union Castle Line to South Africa) which provided

valuable funding.

The Shelter was effective and became trusted, and

more confident: for instance, in 1892 it ended the stealing of luggage

in Hamburg, in 1893 it co-operated with the Port of London Authority

medical officer in coping with a cholera epidemic; in 1896 it resolved

issues with exploited emigrants at the Dutch frontier, and in 1905

similar issues at German borders. At the turn of the century the

superintendent met every incoming ship carrying immigrants (receiving

notice by telegraph) to prevent abuses. Huge numbers passed

through its hands, some at short notice (253 Jews expelled by the Boers

in 1900, and a few months later 650 Romanians); between 1902-05 they

had assisted 16,000, some of whom were painstakingly processed

for onward journeys to the USA, for which a special ship was chartered.

But tension with the police remained - Landau explained that many

victims regarded the police as much the same as the dreaded objescik whom they had left behind -

and the shelter was raided because it was not registered under the

Common Lodging House Act, so had to stop its minimal charges. There

were more personal and local interventions, including payments for

proving a minyan (the quorum

of ten males to enable synagogue services), and issues about who should

receive immigrants on the Sabbath and at festivals.

Early annual reports on the Shelter's work were defensive: most

immigrants were healthy and had good work skills, they said; the

accommodation was deliberately basic and temporary, and supported by

weekly subscriptions from other settlers; and by providing protection

against exploitation by the dockside 'crimpers' they enabled those who

wished to

move on, particularly to the USA or South Africa, to do so, with the

help of other welfare agencies which quickly developed the skills to enable this. By 1890 numbers had increased by 50%, but many

of these achieved 'transmigration' - or even a return home. Indeed, in

the coming decade the shelter negotiated agencies with shipping lines

(especially the Union Castle Line to South Africa) which provided

valuable funding.

The Shelter was effective and became trusted, and

more confident: for instance, in 1892 it ended the stealing of luggage

in Hamburg, in 1893 it co-operated with the Port of London Authority

medical officer in coping with a cholera epidemic; in 1896 it resolved

issues with exploited emigrants at the Dutch frontier, and in 1905

similar issues at German borders. At the turn of the century the

superintendent met every incoming ship carrying immigrants (receiving

notice by telegraph) to prevent abuses. Huge numbers passed

through its hands, some at short notice (253 Jews expelled by the Boers

in 1900, and a few months later 650 Romanians); between 1902-05 they

had assisted 16,000, some of whom were painstakingly processed

for onward journeys to the USA, for which a special ship was chartered.

But tension with the police remained - Landau explained that many

victims regarded the police as much the same as the dreaded objescik whom they had left behind -

and the shelter was raided because it was not registered under the

Common Lodging House Act, so had to stop its minimal charges. There

were more personal and local interventions, including payments for

proving a minyan (the quorum

of ten males to enable synagogue services), and issues about who should

receive immigrants on the Sabbath and at festivals.

What radically changed the nature of the Shelter's work was the 1905

Aliens Act, mentioned above, which restricted immigration on public health and housing grounds: see Bernard Gainer The Alien Invasion: the origins of the Aliens Act of 1905 (Heinemann 1972). Herbert Asquith, the Liberal Home

Secretary, had recently visited the Shelter and spoke of the plight of

the Russian refugees he had met, but the Act was passed, and

henceforward the Shelter became involved in advocacy, translation,

appeal work and guaranteeing bonds for would-be migrants. There was

also work with non-Jewish migrants, including in 1910 an appeal from

the Thompson Line to help travellers to the USA and Australia, and

assistance given to Canada-bound emigrants whose ship had caught fire.

But up to and through the First World War the priority to help eastern

European Jews remained (during the war, some came via Belgium).

In 1906 the Shelter had moved to 63 Mansell Street [right, today - rebuilt in 1930 in neo-Georgian style by Lewis Solomon]; in 1914 the word 'poor' was removed from the title. There were various

crises in the inter-war period, such as the 1923 change in US

immigration law which stranded many; but, of course, the greater crisis

came from Europe itself. By 1937 1,183,000 people had been met at the

docks (and they were now being met at railway stations too); 126,000 had

stayed at the shelter, including a fair number of non-Jews, as noted in a 1937 appeal (endorsed

by the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig with a pamplet House of a Thousand

Destinies). During the Second World War bombed-out

locals were accommodated, until the buildng was requisitioned for

American troops in 1943, and was used after the war to receive children

from displaced persons camps and refugees from Europe and the middle

East.

In 1906 the Shelter had moved to 63 Mansell Street [right, today - rebuilt in 1930 in neo-Georgian style by Lewis Solomon]; in 1914 the word 'poor' was removed from the title. There were various

crises in the inter-war period, such as the 1923 change in US

immigration law which stranded many; but, of course, the greater crisis

came from Europe itself. By 1937 1,183,000 people had been met at the

docks (and they were now being met at railway stations too); 126,000 had

stayed at the shelter, including a fair number of non-Jews, as noted in a 1937 appeal (endorsed

by the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig with a pamplet House of a Thousand

Destinies). During the Second World War bombed-out

locals were accommodated, until the buildng was requisitioned for

American troops in 1943, and was used after the war to receive children

from displaced persons camps and refugees from Europe and the middle

East.

The work was now increasingly advisory, and in 1973 the Shelter moved

to smaller (25-bed) well-appointed premises in Mapesbury Road, Kilburn,

but because of changes in the law this was under-used; it closed in

the 1990s (it is leased for student accommodation), and a part-time

administrator now uses the funds for emergency grants. (The Mansell

Street building is now a private clinic, but retains the name-plate - right.)

Jews' Free School; self-help organisations

The school had

been founded by Joshua van Oven in 1817, in Bell Lane, Spitalfields [Great Hall left] -

through traces its origins back to a Talmud Torah set up for a couple

of dozen orphan boys in 1732 by affluent members of the Ashkenazi Great

Synagogue. By the turn of the 20th century, supported by the

Rothschilds, it laid claim to

be the

largest secondary school in the world, with over 4,000 pupils (boys and

girls) [doorway left]. [The 'JFS' is now in Kenton, and in recent years has been involved in

controversy over its admissions policy.]

The school had

been founded by Joshua van Oven in 1817, in Bell Lane, Spitalfields [Great Hall left] -

through traces its origins back to a Talmud Torah set up for a couple

of dozen orphan boys in 1732 by affluent members of the Ashkenazi Great

Synagogue. By the turn of the 20th century, supported by the

Rothschilds, it laid claim to

be the

largest secondary school in the world, with over 4,000 pupils (boys and

girls) [doorway left]. [The 'JFS' is now in Kenton, and in recent years has been involved in

controversy over its admissions policy.]

Self-help organisations burgeoned. The ethos of the friendly society

- often coupled with ritual and regalia, and status for its officers -

had a particular appeal. The order Achei Brith, founded in 1888, had

2,800 members over thirty lodges, and a capital fund of £7,000. There

was also the Grand Order of Israel, the Hebrew Order of Druids [sic!]

and the Ancient Order of Maccabæans (an early advocate of the Zionist

cause), and smaller associations named after Russian and Polish towns,

of which the Cracow Jewish Friendly Society (established 1864, first meeting at the Angel and Crown in Whitechapel, and in due course claiming about 380 members,

with a base at the Cannon Street Road Synagogue), was the largest.

'The Hutch'

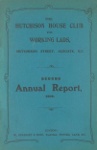

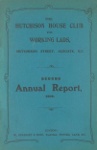

In 1872 a Jewish Working Men's Club & Lads' Institute

had been founded by the Jewish Association for the Diffusion of

Religious Knowledge, with a reading room and lecture hall at Hutchison

House, Hutchison Street, Aldgate; Samuel Montagu

was President. Becoming independent two years later, they added a

library, games, entertainments and other club features for 400 members

of both sexes. In 1883, a purpose-built club for 1,500 was built in

Great Alie Street, with a Lads' Institute for boys between 14 and 20.

Membership continued to increase; the Lads' Institute returned to

Hutchison Street, and in 1892 the Great Alie Street premises were

enlarged at a cost of £4,000. By 1905 there were 975 members, and the Hutchison House Club

was created by the Rothschild family in conjunction with Max Bonn

(1877-1938, an American-born merchant banker, later Sir Max Bonn KBE)

and Frank Goldsmith MP, based at Camperdown House, in Half Moon

Passage. (In 1915 they offered these premises to the government for war

work; in 1918 the newly-raised Jewish Battalion

of the 38th Royal Fusiliers had a kosher meal here and was inspected

in Great Alie Street by Lt. Gen. Sir Francis Lloyd, as part of its

famous march through Whitechapel; in the 1920s, social work conferences

were held here.)

In 1872 a Jewish Working Men's Club & Lads' Institute

had been founded by the Jewish Association for the Diffusion of

Religious Knowledge, with a reading room and lecture hall at Hutchison

House, Hutchison Street, Aldgate; Samuel Montagu

was President. Becoming independent two years later, they added a

library, games, entertainments and other club features for 400 members

of both sexes. In 1883, a purpose-built club for 1,500 was built in

Great Alie Street, with a Lads' Institute for boys between 14 and 20.

Membership continued to increase; the Lads' Institute returned to

Hutchison Street, and in 1892 the Great Alie Street premises were

enlarged at a cost of £4,000. By 1905 there were 975 members, and the Hutchison House Club

was created by the Rothschild family in conjunction with Max Bonn

(1877-1938, an American-born merchant banker, later Sir Max Bonn KBE)

and Frank Goldsmith MP, based at Camperdown House, in Half Moon

Passage. (In 1915 they offered these premises to the government for war

work; in 1918 the newly-raised Jewish Battalion

of the 38th Royal Fusiliers had a kosher meal here and was inspected

in Great Alie Street by Lt. Gen. Sir Francis Lloyd, as part of its

famous march through Whitechapel; in the 1920s, social work conferences

were held here.)

It

thus became one of several local agencies committed to encouraging

young people to combine loyalty to faith and citizenship - see below

for another example - particularly through sport ('the sunshine of

manly sports and pastimes'). It was also the HQ of the Jewish Lads' and

Girls' Brigade (in some rivalry with Jewish scout troops). When the

club closed, administrative activities transferred to north London; in

more recent times, it has funded a London University research

fellowship: see Sharman Kadish A Good Jew and a Good Englishman (Vallentine Mitchell 1995). Pictured is present-day Camperdown House, an office block at 6 Braham Street.

It

thus became one of several local agencies committed to encouraging

young people to combine loyalty to faith and citizenship - see below

for another example - particularly through sport ('the sunshine of

manly sports and pastimes'). It was also the HQ of the Jewish Lads' and

Girls' Brigade (in some rivalry with Jewish scout troops). When the

club closed, administrative activities transferred to north London; in

more recent times, it has funded a London University research

fellowship: see Sharman Kadish A Good Jew and a Good Englishman (Vallentine Mitchell 1995). Pictured is present-day Camperdown House, an office block at 6 Braham Street.

(See here for the Jewish Working Girls' Club, established in Leman Street in 1886.)

Political and Friendly Societies: Workers' Circle (Arbeiter Ring), Workers' Friend (Arbeiter Fraint)

The

centre of working-class left wing activism was the Workers'

Circle,

which functioned as a friendly society and a cultural, social and

political club, established by cabinet-makers in an upstairs room in

Brick Lane in 1909. Its membership was

broad, including trade unionists, Marxists and Communists, Labour Party

members, anarchists and Zionists. Between the wars 20 branches were

established, in London and elsewhere, with total membership rising to

about 3,000 by 1939, after which it declined (it disbanded in 1985).

It owned a rest home in Littlehampton. Symons House at 22 Alie

Street [right today] became its

headquarters in 1924, providing lectures,

concerts, dances, debates and classes. Workers gathered in its canteen

to read newspapers, drink tea and argue, finding, as one writer put it, consolation, a spiritual refuge from their

struggle with the day-to-day world, a place to recharge their dreams. [The only Jewish Friendly Society now remaining is The Grand Order of David and Shield of Israel Friendly Society, which now functions solely as a social club.]

The

centre of working-class left wing activism was the Workers'

Circle,

which functioned as a friendly society and a cultural, social and

political club, established by cabinet-makers in an upstairs room in

Brick Lane in 1909. Its membership was

broad, including trade unionists, Marxists and Communists, Labour Party

members, anarchists and Zionists. Between the wars 20 branches were

established, in London and elsewhere, with total membership rising to

about 3,000 by 1939, after which it declined (it disbanded in 1985).

It owned a rest home in Littlehampton. Symons House at 22 Alie

Street [right today] became its

headquarters in 1924, providing lectures,

concerts, dances, debates and classes. Workers gathered in its canteen

to read newspapers, drink tea and argue, finding, as one writer put it, consolation, a spiritual refuge from their

struggle with the day-to-day world, a place to recharge their dreams. [The only Jewish Friendly Society now remaining is The Grand Order of David and Shield of Israel Friendly Society, which now functions solely as a social club.]

40 Berner [Henriques] Street housed the International Working Men's Club, and was also for a time the print works of the anarchist Yiddish newspaper Arbeiter Fraint (Workers’ Friend), which was edited for a time by Rudolf Rocker [left, a

painting by his son Fermin] who came to London from Germany in the

1890s. But in 1900 one of many financial crises forced a move to a smelly shed

in Stepney Green. See further Bill Fishman East End Jewish Radicals 1875 -1914. Jewish anarchists and socialists have been active in the area ever since.

40 Berner [Henriques] Street housed the International Working Men's Club, and was also for a time the print works of the anarchist Yiddish newspaper Arbeiter Fraint (Workers’ Friend), which was edited for a time by Rudolf Rocker [left, a

painting by his son Fermin] who came to London from Germany in the

1890s. But in 1900 one of many financial crises forced a move to a smelly shed

in Stepney Green. See further Bill Fishman East End Jewish Radicals 1875 -1914. Jewish anarchists and socialists have been active in the area ever since.

Theatres

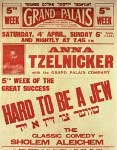

A regular topic of conversation in the street was the productions at

the two Yiddish theatres in the area, the Pavilion Theatre in

Whitechapel Road (closed in 1936) and the Grand Palais at 131-139 Commercial Road (opposite Umberston Street). The Grand

Palais [doorway left] opened in 1926 in a former cinema, and survived in regular use

until 1961 [left are Leo Fuchs and the company rehearsing in 1956, and Max Bacon, a regular

performer - on the right of the photo], with occasional performances

until 1970 when it became a bingo hall.

A regular topic of conversation in the street was the productions at

the two Yiddish theatres in the area, the Pavilion Theatre in

Whitechapel Road (closed in 1936) and the Grand Palais at 131-139 Commercial Road (opposite Umberston Street). The Grand

Palais [doorway left] opened in 1926 in a former cinema, and survived in regular use

until 1961 [left are Leo Fuchs and the company rehearsing in 1956, and Max Bacon, a regular

performer - on the right of the photo], with occasional performances

until 1970 when it became a bingo hall.

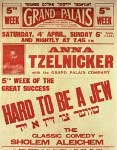

Its most

famous production was the 1943 wartime hit musical Der Kenig fun Lampeduza (The

King of Lampedusa), starring Romanian-born Meier Tzelniker (1898-1980)

and his daughter Anna,

b.1922 [left, plus a poster for another production]. (See here for the 2013 Lampedusa boat tragedy.) They also acted together in Yiddish productions of

Shakespeare (e.g. Meier as Shylock and Anna as Portia in The Merchant of Venice, in 1946 - a thrilling experience, said the Jewish Chronicle),

put on by the Jewish National Theatre which Meier formed in 1936 with

Fanny Waxman (Anna's husband Phil Bernstein became its musical

director). Anna also featured in Lionel Bart's Blitz!, singing 'Petticoat Lane (on a Saturday ain't so nice)', and in more recent years regularly

recited her father's Yiddish poem about Hessel Street Market. The Grand Palais site now houses Flick Fashions [right],

whose main offices are round the corner in Cavell Street: part of the

doorway remains. Footage of the theatre can be seen in the 1967 James

Mason film The London Nobody Knows.

Its most

famous production was the 1943 wartime hit musical Der Kenig fun Lampeduza (The

King of Lampedusa), starring Romanian-born Meier Tzelniker (1898-1980)

and his daughter Anna,

b.1922 [left, plus a poster for another production]. (See here for the 2013 Lampedusa boat tragedy.) They also acted together in Yiddish productions of

Shakespeare (e.g. Meier as Shylock and Anna as Portia in The Merchant of Venice, in 1946 - a thrilling experience, said the Jewish Chronicle),

put on by the Jewish National Theatre which Meier formed in 1936 with

Fanny Waxman (Anna's husband Phil Bernstein became its musical

director). Anna also featured in Lionel Bart's Blitz!, singing 'Petticoat Lane (on a Saturday ain't so nice)', and in more recent years regularly

recited her father's Yiddish poem about Hessel Street Market. The Grand Palais site now houses Flick Fashions [right],

whose main offices are round the corner in Cavell Street: part of the

doorway remains. Footage of the theatre can be seen in the 1967 James

Mason film The London Nobody Knows.

Thus

over time what has been described as a 'miniature welfare state' for

the Jewish East End, with various political complexions, emerged. See this (racist) article of 1894 about anarchist groups. This 1896 article comments on the

range of Jewish activities in Whitechapel, and this 1911 article

favourably but somewhat sentimentally contrasts the 'Jewish' end of Cable Street,

around the Shelter, with its 'Irish' end.

Vibrant

patterns of Jewish life had emerged, with Yiddish newspapers, theatres, the Hessel Street market

and many social, philanthropic and political

organisations. The First World War brought sharp tensions, as many

German and Austrian-born Jews were interned under the Aliens

Restriction Act of 1914. Samuel Montagu, Lord Rothschild and other members of the Board of Deputies of British Jews were the signatories of this letter appealing for help on behalf of the Russo-Jewish Committee in London to assist the

victims of the pogroms in Russia.

See further pages on local Jewish life:

Jewish Presence (2) - Synagogues in the parish

Jewish Presence (3) - St George's Settlement Synagogue

Jewish Presence (4) - Hessel Street

Jewish Presence (5) - convert clergy

Back to History page

note:

the Whitechapel Gallery, a fine Arts & Crafts building of 1901 designed by Charles Harrison Townsend, restored and extended in 2009, became a

focal point for Jewish intellectual life in the area ('the University of the Ghetto'), and its reading

room and exhibitions reflect this, as does Bernard Kops' poem Whitechapel Library, Aldgate East. Our local First World War poet Isaac Rosenberg is commemorated here with a blue plaque.The London Metropolitan Archives has

a good display of Jewish life in the East End, based around a wall-size

version of the map shown below.

note:

the Whitechapel Gallery, a fine Arts & Crafts building of 1901 designed by Charles Harrison Townsend, restored and extended in 2009, became a

focal point for Jewish intellectual life in the area ('the University of the Ghetto'), and its reading

room and exhibitions reflect this, as does Bernard Kops' poem Whitechapel Library, Aldgate East. Our local First World War poet Isaac Rosenberg is commemorated here with a blue plaque.The London Metropolitan Archives has

a good display of Jewish life in the East End, based around a wall-size

version of the map shown below.

G. Eugene

Harfield's handsomely-printed Commercial

Directory of the Jews of the United Kingdom (Hewlett

& Pierce 5634/1894), listing established traders and professionals

(including barristers) throughout the land, is a sign of the desire to

make good by assimilation, which a flood of poor immigrants threatened

- see below. Significantly, its title page [right] combines Palestinian

aspirations and loyalty to the Crown. (See here

for the listings of shops and businesses in this parish.) By

contrast, many

eastern European immigrants espoused radical politics: see here for

a scurrilous, and racist, article from the Evening Standard of

1894 on the 'haunts of the anarchists'.

G. Eugene

Harfield's handsomely-printed Commercial

Directory of the Jews of the United Kingdom (Hewlett

& Pierce 5634/1894), listing established traders and professionals

(including barristers) throughout the land, is a sign of the desire to

make good by assimilation, which a flood of poor immigrants threatened

- see below. Significantly, its title page [right] combines Palestinian

aspirations and loyalty to the Crown. (See here

for the listings of shops and businesses in this parish.) By

contrast, many

eastern European immigrants espoused radical politics: see here for

a scurrilous, and racist, article from the Evening Standard of

1894 on the 'haunts of the anarchists'. Russell & Lewis's 1900 map of Jewish East London [right] shows the density of Jewish settlement street by

street - from dark blue (over 95%) to dark pink (less than 5%). In this

parish, the dark blue areas were all north of the railway line: from

west to east, the Goodman's Fields area (then part of St Mark

Whitechapel), some streets to the east of Backchurch Lane (then part of

St John's parish), the area round Rampart Street, and the top of Watney

Street (then part of Christ Church parish). South of the railway, only

Cannon Street Road and Cable Street were predominantly Jewish, plus the

area north of the railway and west of Cannon Street Road. All other parts

of the parish are light or dark pink - including a few patches in the

Jewish 'heartlands': some of these were predominantly Irish.

Russell & Lewis's 1900 map of Jewish East London [right] shows the density of Jewish settlement street by

street - from dark blue (over 95%) to dark pink (less than 5%). In this

parish, the dark blue areas were all north of the railway line: from

west to east, the Goodman's Fields area (then part of St Mark

Whitechapel), some streets to the east of Backchurch Lane (then part of

St John's parish), the area round Rampart Street, and the top of Watney

Street (then part of Christ Church parish). South of the railway, only

Cannon Street Road and Cable Street were predominantly Jewish, plus the

area north of the railway and west of Cannon Street Road. All other parts

of the parish are light or dark pink - including a few patches in the

Jewish 'heartlands': some of these were predominantly Irish.

Before

1939 there were some 80,000 Jews in the East End

and about 70 synagogues. However, although most homes were 'observant'

- keeping Sabbath and some or all of the dietary laws - synagogue

attendance was probably not more than 25% in most areas. The

institutions that promoted assimilation, education and career

aspiration were victims of their own success, with many of the

community prospering, moving on and 'marrying out'. Today it is

estimated that there are between two and three thousand Jews in the

'traditional' East End. There is not

a single kosher butcher (though plenty of halal ones), and the three

surviving synagogues struggle to

maintain a minyan (quorum of ten men) for the Shabbat service; others

have disappeared, often without a trace. But the Stepney Jewish Day

Centre (run by Jewish Care)

hosts about 700 people a week, and provides kosher meals on wheels.

There is a Jewish Society at Queen Mary College. And there are a few

remaining food shops, including Carmel Wines on the Mile End Road

(strictly kosher), some non-Beth Din bakers selling traditional bagels,

and Tubby Isaac's famous jellied eel stall remains near Aldgate East

station [right, then and now]: a commodity once common to all East Enders, which fell out of favour, but has recently become trendy.

Before

1939 there were some 80,000 Jews in the East End

and about 70 synagogues. However, although most homes were 'observant'

- keeping Sabbath and some or all of the dietary laws - synagogue

attendance was probably not more than 25% in most areas. The

institutions that promoted assimilation, education and career

aspiration were victims of their own success, with many of the

community prospering, moving on and 'marrying out'. Today it is

estimated that there are between two and three thousand Jews in the

'traditional' East End. There is not

a single kosher butcher (though plenty of halal ones), and the three

surviving synagogues struggle to

maintain a minyan (quorum of ten men) for the Shabbat service; others

have disappeared, often without a trace. But the Stepney Jewish Day

Centre (run by Jewish Care)

hosts about 700 people a week, and provides kosher meals on wheels.

There is a Jewish Society at Queen Mary College. And there are a few

remaining food shops, including Carmel Wines on the Mile End Road

(strictly kosher), some non-Beth Din bakers selling traditional bagels,

and Tubby Isaac's famous jellied eel stall remains near Aldgate East

station [right, then and now]: a commodity once common to all East Enders, which fell out of favour, but has recently become trendy. Lord Rothschild

(Nathaniel 'Natty' Mayer Rothschild) [right], head of the family bank after his

father's death in 1879, and the first (observant) Jewish peer (voting

with the Conservative and Unionists) was a key founder of the Four Per Cent Industrial Dwellings Company following the United Synagogue's 1884 enquiry into

'spiritual destitution'. Most of the patrons and tenants of their

'model artisan dwellings' were Jewish, particularly at the

Rothschild Buildings in Flower and Dean Street, which became a focal

point of Jewish life - see Jerry White Rothschild

Buildings: Life in an East End Tenement Block, 1887-1920 (Routledge

1980). (The company later built Albert Buildings

next to the Peabody Estate.) Notably, until his death in 1915, Lord Rothschild

was a trustee of the London Mosque Fund - a rôle later held by Lord Winterton.

Lord Rothschild

(Nathaniel 'Natty' Mayer Rothschild) [right], head of the family bank after his

father's death in 1879, and the first (observant) Jewish peer (voting

with the Conservative and Unionists) was a key founder of the Four Per Cent Industrial Dwellings Company following the United Synagogue's 1884 enquiry into

'spiritual destitution'. Most of the patrons and tenants of their

'model artisan dwellings' were Jewish, particularly at the

Rothschild Buildings in Flower and Dean Street, which became a focal

point of Jewish life - see Jerry White Rothschild

Buildings: Life in an East End Tenement Block, 1887-1920 (Routledge

1980). (The company later built Albert Buildings

next to the Peabody Estate.) Notably, until his death in 1915, Lord Rothschild

was a trustee of the London Mosque Fund - a rôle later held by Lord Winterton.

In 1885 a baker Simon Cohen, aka Becker, began to provide

temporary shelter at his premises in Church Lane, Whitechapel, but the

Board of Guardians closed it down: as the Jewish Chronicle reported, Its

abject misery is worse than any workhouse and it provides less food.

There is absolutely no sleeping accommodation except a wooden floor.

The only kind of daily food is rice and tea and bread and this is very

irregular. Let us get a ‘responsible committee’ or let a few gentlemen

see if they cannot get a few cheap mattresses for the older men to lie

upon at night and some blankets or rugs. Hermann Landau [right, and pictured welcoming immigrants at the Shelter], a

banker who had come from Poland in 1864 and had become an influential

member of the Jewish community, rose to the challenge, with a couple of

others (and, in the early years, some Rothschild funding), and in 1886

the Jews' Temporary Shelter was established at 84 Leman Street [left] as an institution

in which newcomers, having a little money, might obtain accommodation

and the necessaries they required at cost price, and where they would

receive useful advice. (It's said that its address was traded across eastern Europe to aspiring emigrants.) Those with some resources were referred

to local lodging houses, where they were soon propositioned by

furniture contractors and landlords; those without were

referred to the Soup Kitchen for the Jewish Poor and other charitable

bodies. In 1895 it received substantial

funding from another banker-philanthropist, Samuel Montagu [right], who became a Liberal MP and later a peer.

In 1885 a baker Simon Cohen, aka Becker, began to provide

temporary shelter at his premises in Church Lane, Whitechapel, but the

Board of Guardians closed it down: as the Jewish Chronicle reported, Its

abject misery is worse than any workhouse and it provides less food.

There is absolutely no sleeping accommodation except a wooden floor.

The only kind of daily food is rice and tea and bread and this is very

irregular. Let us get a ‘responsible committee’ or let a few gentlemen

see if they cannot get a few cheap mattresses for the older men to lie

upon at night and some blankets or rugs. Hermann Landau [right, and pictured welcoming immigrants at the Shelter], a

banker who had come from Poland in 1864 and had become an influential

member of the Jewish community, rose to the challenge, with a couple of

others (and, in the early years, some Rothschild funding), and in 1886

the Jews' Temporary Shelter was established at 84 Leman Street [left] as an institution

in which newcomers, having a little money, might obtain accommodation

and the necessaries they required at cost price, and where they would

receive useful advice. (It's said that its address was traded across eastern Europe to aspiring emigrants.) Those with some resources were referred

to local lodging houses, where they were soon propositioned by

furniture contractors and landlords; those without were

referred to the Soup Kitchen for the Jewish Poor and other charitable

bodies. In 1895 it received substantial

funding from another banker-philanthropist, Samuel Montagu [right], who became a Liberal MP and later a peer.

Early annual reports on the Shelter's work were defensive: most

immigrants were healthy and had good work skills, they said; the

accommodation was deliberately basic and temporary, and supported by

weekly subscriptions from other settlers; and by providing protection

against exploitation by the dockside 'crimpers' they enabled those who

wished to

move on, particularly to the USA or South Africa, to do so, with the

help of other welfare agencies which quickly developed the skills to enable this. By 1890 numbers had increased by 50%, but many

of these achieved 'transmigration' - or even a return home. Indeed, in

the coming decade the shelter negotiated agencies with shipping lines

(especially the Union Castle Line to South Africa) which provided

valuable funding.

The Shelter was effective and became trusted, and

more confident: for instance, in 1892 it ended the stealing of luggage

in Hamburg, in 1893 it co-operated with the Port of London Authority

medical officer in coping with a cholera epidemic; in 1896 it resolved

issues with exploited emigrants at the Dutch frontier, and in 1905

similar issues at German borders. At the turn of the century the

superintendent met every incoming ship carrying immigrants (receiving

notice by telegraph) to prevent abuses. Huge numbers passed

through its hands, some at short notice (253 Jews expelled by the Boers

in 1900, and a few months later 650 Romanians); between 1902-05 they

had assisted 16,000, some of whom were painstakingly processed

for onward journeys to the USA, for which a special ship was chartered.

But tension with the police remained - Landau explained that many

victims regarded the police as much the same as the dreaded objescik whom they had left behind -

and the shelter was raided because it was not registered under the

Common Lodging House Act, so had to stop its minimal charges. There

were more personal and local interventions, including payments for

proving a minyan (the quorum

of ten males to enable synagogue services), and issues about who should

receive immigrants on the Sabbath and at festivals.

Early annual reports on the Shelter's work were defensive: most

immigrants were healthy and had good work skills, they said; the

accommodation was deliberately basic and temporary, and supported by

weekly subscriptions from other settlers; and by providing protection

against exploitation by the dockside 'crimpers' they enabled those who

wished to

move on, particularly to the USA or South Africa, to do so, with the

help of other welfare agencies which quickly developed the skills to enable this. By 1890 numbers had increased by 50%, but many

of these achieved 'transmigration' - or even a return home. Indeed, in

the coming decade the shelter negotiated agencies with shipping lines

(especially the Union Castle Line to South Africa) which provided

valuable funding.

The Shelter was effective and became trusted, and

more confident: for instance, in 1892 it ended the stealing of luggage

in Hamburg, in 1893 it co-operated with the Port of London Authority

medical officer in coping with a cholera epidemic; in 1896 it resolved

issues with exploited emigrants at the Dutch frontier, and in 1905

similar issues at German borders. At the turn of the century the

superintendent met every incoming ship carrying immigrants (receiving

notice by telegraph) to prevent abuses. Huge numbers passed

through its hands, some at short notice (253 Jews expelled by the Boers

in 1900, and a few months later 650 Romanians); between 1902-05 they

had assisted 16,000, some of whom were painstakingly processed

for onward journeys to the USA, for which a special ship was chartered.

But tension with the police remained - Landau explained that many

victims regarded the police as much the same as the dreaded objescik whom they had left behind -

and the shelter was raided because it was not registered under the

Common Lodging House Act, so had to stop its minimal charges. There

were more personal and local interventions, including payments for

proving a minyan (the quorum

of ten males to enable synagogue services), and issues about who should

receive immigrants on the Sabbath and at festivals.

In 1906 the Shelter had moved to 63 Mansell Street [right, today - rebuilt in 1930 in neo-Georgian style by Lewis Solomon]; in 1914 the word 'poor' was removed from the title. There were various

crises in the inter-war period, such as the 1923 change in US

immigration law which stranded many; but, of course, the greater crisis

came from Europe itself. By 1937 1,183,000 people had been met at the

docks (and they were now being met at railway stations too); 126,000 had

stayed at the shelter, including a fair number of non-Jews, as noted in a 1937 appeal (endorsed

by the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig with a pamplet House of a Thousand

Destinies). During the Second World War bombed-out

locals were accommodated, until the buildng was requisitioned for

American troops in 1943, and was used after the war to receive children

from displaced persons camps and refugees from Europe and the middle

East.

In 1906 the Shelter had moved to 63 Mansell Street [right, today - rebuilt in 1930 in neo-Georgian style by Lewis Solomon]; in 1914 the word 'poor' was removed from the title. There were various

crises in the inter-war period, such as the 1923 change in US

immigration law which stranded many; but, of course, the greater crisis

came from Europe itself. By 1937 1,183,000 people had been met at the

docks (and they were now being met at railway stations too); 126,000 had

stayed at the shelter, including a fair number of non-Jews, as noted in a 1937 appeal (endorsed

by the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig with a pamplet House of a Thousand

Destinies). During the Second World War bombed-out

locals were accommodated, until the buildng was requisitioned for

American troops in 1943, and was used after the war to receive children

from displaced persons camps and refugees from Europe and the middle

East.

The school had

been founded by Joshua van Oven in 1817, in Bell Lane, Spitalfields [Great Hall left] -

through traces its origins back to a Talmud Torah set up for a couple

of dozen orphan boys in 1732 by affluent members of the Ashkenazi Great

Synagogue. By the turn of the 20th century, supported by the

Rothschilds, it laid claim to

be the

largest secondary school in the world, with over 4,000 pupils (boys and

girls) [doorway left]. [The 'JFS' is now in Kenton, and in recent years has been involved in

controversy over its admissions policy.]

The school had

been founded by Joshua van Oven in 1817, in Bell Lane, Spitalfields [Great Hall left] -

through traces its origins back to a Talmud Torah set up for a couple

of dozen orphan boys in 1732 by affluent members of the Ashkenazi Great

Synagogue. By the turn of the 20th century, supported by the

Rothschilds, it laid claim to

be the

largest secondary school in the world, with over 4,000 pupils (boys and

girls) [doorway left]. [The 'JFS' is now in Kenton, and in recent years has been involved in

controversy over its admissions policy.]  In 1872 a Jewish Working Men's Club & Lads' Institute

had been founded by the Jewish Association for the Diffusion of

Religious Knowledge, with a reading room and lecture hall at Hutchison

House, Hutchison Street, Aldgate; Samuel Montagu

was President. Becoming independent two years later, they added a

library, games, entertainments and other club features for 400 members

of both sexes. In 1883, a purpose-built club for 1,500 was built in

Great Alie Street, with a Lads' Institute for boys between 14 and 20.

Membership continued to increase; the Lads' Institute returned to

Hutchison Street, and in 1892 the Great Alie Street premises were

enlarged at a cost of £4,000. By 1905 there were 975 members, and the Hutchison House Club

was created by the Rothschild family in conjunction with Max Bonn

(1877-1938, an American-born merchant banker, later Sir Max Bonn KBE)

and Frank Goldsmith MP, based at Camperdown House, in Half Moon

Passage. (In 1915 they offered these premises to the government for war

work; in 1918 the newly-raised Jewish Battalion

of the 38th Royal Fusiliers had a kosher meal here and was inspected

in Great Alie Street by Lt. Gen. Sir Francis Lloyd, as part of its

famous march through Whitechapel; in the 1920s, social work conferences

were held here.)

In 1872 a Jewish Working Men's Club & Lads' Institute

had been founded by the Jewish Association for the Diffusion of

Religious Knowledge, with a reading room and lecture hall at Hutchison

House, Hutchison Street, Aldgate; Samuel Montagu

was President. Becoming independent two years later, they added a

library, games, entertainments and other club features for 400 members

of both sexes. In 1883, a purpose-built club for 1,500 was built in

Great Alie Street, with a Lads' Institute for boys between 14 and 20.

Membership continued to increase; the Lads' Institute returned to

Hutchison Street, and in 1892 the Great Alie Street premises were

enlarged at a cost of £4,000. By 1905 there were 975 members, and the Hutchison House Club

was created by the Rothschild family in conjunction with Max Bonn

(1877-1938, an American-born merchant banker, later Sir Max Bonn KBE)

and Frank Goldsmith MP, based at Camperdown House, in Half Moon

Passage. (In 1915 they offered these premises to the government for war

work; in 1918 the newly-raised Jewish Battalion

of the 38th Royal Fusiliers had a kosher meal here and was inspected

in Great Alie Street by Lt. Gen. Sir Francis Lloyd, as part of its

famous march through Whitechapel; in the 1920s, social work conferences

were held here.)  It

thus became one of several local agencies committed to encouraging

young people to combine loyalty to faith and citizenship - see below

for another example - particularly through sport ('the sunshine of

manly sports and pastimes'). It was also the HQ of the Jewish Lads' and

Girls' Brigade (in some rivalry with Jewish scout troops). When the

club closed, administrative activities transferred to north London; in

more recent times, it has funded a London University research

fellowship: see Sharman Kadish A Good Jew and a Good Englishman (Vallentine Mitchell 1995). Pictured is present-day Camperdown House, an office block at 6 Braham Street.

It

thus became one of several local agencies committed to encouraging

young people to combine loyalty to faith and citizenship - see below

for another example - particularly through sport ('the sunshine of

manly sports and pastimes'). It was also the HQ of the Jewish Lads' and

Girls' Brigade (in some rivalry with Jewish scout troops). When the

club closed, administrative activities transferred to north London; in

more recent times, it has funded a London University research

fellowship: see Sharman Kadish A Good Jew and a Good Englishman (Vallentine Mitchell 1995). Pictured is present-day Camperdown House, an office block at 6 Braham Street. The

centre of working-class left wing activism was the Workers'

Circle,

which functioned as a friendly society and a cultural, social and

political club, established by cabinet-makers in an upstairs room in

Brick Lane in 1909. Its membership was

broad, including trade unionists, Marxists and Communists, Labour Party

members, anarchists and Zionists. Between the wars 20 branches were

established, in London and elsewhere, with total membership rising to

about 3,000 by 1939, after which it declined (it disbanded in 1985).

It owned a rest home in Littlehampton. Symons House at 22 Alie

Street [right today] became its

headquarters in 1924, providing lectures,

concerts, dances, debates and classes. Workers gathered in its canteen

to read newspapers, drink tea and argue, finding, as one writer put it, consolation, a spiritual refuge from their

struggle with the day-to-day world, a place to recharge their dreams. [The only Jewish Friendly Society now remaining is The Grand Order of David and Shield of Israel Friendly Society, which now functions solely as a social club.]

The

centre of working-class left wing activism was the Workers'

Circle,

which functioned as a friendly society and a cultural, social and

political club, established by cabinet-makers in an upstairs room in

Brick Lane in 1909. Its membership was

broad, including trade unionists, Marxists and Communists, Labour Party

members, anarchists and Zionists. Between the wars 20 branches were

established, in London and elsewhere, with total membership rising to

about 3,000 by 1939, after which it declined (it disbanded in 1985).

It owned a rest home in Littlehampton. Symons House at 22 Alie

Street [right today] became its

headquarters in 1924, providing lectures,

concerts, dances, debates and classes. Workers gathered in its canteen

to read newspapers, drink tea and argue, finding, as one writer put it, consolation, a spiritual refuge from their

struggle with the day-to-day world, a place to recharge their dreams. [The only Jewish Friendly Society now remaining is The Grand Order of David and Shield of Israel Friendly Society, which now functions solely as a social club.] 40 Berner [Henriques] Street housed the International Working Men's Club, and was also for a time the print works of the anarchist Yiddish newspaper Arbeiter Fraint (Workers’ Friend), which was edited for a time by Rudolf Rocker [left, a

painting by his son Fermin] who came to London from Germany in the

1890s. But in 1900 one of many financial crises forced a move to a smelly shed

in Stepney Green. See further Bill Fishman East End Jewish Radicals 1875 -1914. Jewish anarchists and socialists have been active in the area ever since.

40 Berner [Henriques] Street housed the International Working Men's Club, and was also for a time the print works of the anarchist Yiddish newspaper Arbeiter Fraint (Workers’ Friend), which was edited for a time by Rudolf Rocker [left, a

painting by his son Fermin] who came to London from Germany in the

1890s. But in 1900 one of many financial crises forced a move to a smelly shed

in Stepney Green. See further Bill Fishman East End Jewish Radicals 1875 -1914. Jewish anarchists and socialists have been active in the area ever since.

A regular topic of conversation in the street was the productions at

the two Yiddish theatres in the area, the Pavilion Theatre in

Whitechapel Road (closed in 1936) and the Grand Palais at 131-139 Commercial Road (opposite Umberston Street). The Grand

Palais [doorway left] opened in 1926 in a former cinema, and survived in regular use

until 1961 [left are Leo Fuchs and the company rehearsing in 1956, and Max Bacon, a regular

performer - on the right of the photo], with occasional performances

until 1970 when it became a bingo hall.

A regular topic of conversation in the street was the productions at

the two Yiddish theatres in the area, the Pavilion Theatre in

Whitechapel Road (closed in 1936) and the Grand Palais at 131-139 Commercial Road (opposite Umberston Street). The Grand

Palais [doorway left] opened in 1926 in a former cinema, and survived in regular use

until 1961 [left are Leo Fuchs and the company rehearsing in 1956, and Max Bacon, a regular

performer - on the right of the photo], with occasional performances

until 1970 when it became a bingo hall.

Its most

famous production was the 1943 wartime hit musical Der Kenig fun Lampeduza (The

King of Lampedusa), starring Romanian-born Meier Tzelniker (1898-1980)

and his daughter Anna,

b.1922 [left, plus a poster for another production]. (See here for the 2013 Lampedusa boat tragedy.) They also acted together in Yiddish productions of

Shakespeare (e.g. Meier as Shylock and Anna as Portia in The Merchant of Venice, in 1946 - a thrilling experience, said the Jewish Chronicle),

put on by the Jewish National Theatre which Meier formed in 1936 with

Fanny Waxman (Anna's husband Phil Bernstein became its musical

director). Anna also featured in Lionel Bart's Blitz!, singing 'Petticoat Lane (on a Saturday ain't so nice)', and in more recent years regularly

recited her father's Yiddish poem about Hessel Street Market. The Grand Palais site now houses Flick Fashions [right],

whose main offices are round the corner in Cavell Street: part of the

doorway remains. Footage of the theatre can be seen in the 1967 James

Mason film The London Nobody Knows.

Its most

famous production was the 1943 wartime hit musical Der Kenig fun Lampeduza (The

King of Lampedusa), starring Romanian-born Meier Tzelniker (1898-1980)

and his daughter Anna,

b.1922 [left, plus a poster for another production]. (See here for the 2013 Lampedusa boat tragedy.) They also acted together in Yiddish productions of

Shakespeare (e.g. Meier as Shylock and Anna as Portia in The Merchant of Venice, in 1946 - a thrilling experience, said the Jewish Chronicle),

put on by the Jewish National Theatre which Meier formed in 1936 with

Fanny Waxman (Anna's husband Phil Bernstein became its musical

director). Anna also featured in Lionel Bart's Blitz!, singing 'Petticoat Lane (on a Saturday ain't so nice)', and in more recent years regularly

recited her father's Yiddish poem about Hessel Street Market. The Grand Palais site now houses Flick Fashions [right],

whose main offices are round the corner in Cavell Street: part of the

doorway remains. Footage of the theatre can be seen in the 1967 James

Mason film The London Nobody Knows.