Goodman's Fields (1)

Goodman's Fields (1) In 1515, 27 of the nuns died of infection, and shortly after the

outbreak of plague the convent buildings were destroyed by fire. Rebuilding was aided by contributions from

the mayor, aldermen, and citizens of London to the sum of 200 marks but,

at the special request of Cardinal Wolsey to the Court of Common

Council, it was decided in 1520 to give 100 marks more to complete the

building. The king donated £200. After the Dissolution, the nunnery was surrendered to Henry VIII by the

last abbess, Dame Elizabeth Salvage, in 1539, who was subsequently

granted a pension of £40, and the nunnery became the residence of John

Clark, Bishop of Bath and Wells, Henry VIII’s ambassador to the Duke of

Cleve [left is a drawing of the ruined abbey in 1797].

In 1515, 27 of the nuns died of infection, and shortly after the

outbreak of plague the convent buildings were destroyed by fire. Rebuilding was aided by contributions from

the mayor, aldermen, and citizens of London to the sum of 200 marks but,

at the special request of Cardinal Wolsey to the Court of Common

Council, it was decided in 1520 to give 100 marks more to complete the

building. The king donated £200. After the Dissolution, the nunnery was surrendered to Henry VIII by the

last abbess, Dame Elizabeth Salvage, in 1539, who was subsequently

granted a pension of £40, and the nunnery became the residence of John

Clark, Bishop of Bath and Wells, Henry VIII’s ambassador to the Duke of

Cleve [left is a drawing of the ruined abbey in 1797].

From the 16th century, the open ground was divided

into garden plots. It was bought by Sir John Leman, Lord Mayor of

London, whose great-nephew William Leman laid out four streets, named

after relatives - Mansell, Prescot, Ayliff and Leman. John Strype in 1717 described them as fair streets of good brick houses, but

by the end of the century most were replaced by Richard Leman and his

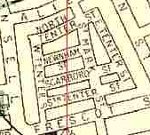

builder Edward Hawkins: the area remained fashionable, until sugar blowing, and then warehouses, encroached. Left is Roque's map of 1746, and right an

1814 map of part of the estate sold after the death of City magnate

William Strode (far right: Hogarth's 1730s picture of the family is in the Tate -

details here.)

From the 16th century, the open ground was divided

into garden plots. It was bought by Sir John Leman, Lord Mayor of

London, whose great-nephew William Leman laid out four streets, named

after relatives - Mansell, Prescot, Ayliff and Leman. John Strype in 1717 described them as fair streets of good brick houses, but

by the end of the century most were replaced by Richard Leman and his

builder Edward Hawkins: the area remained fashionable, until sugar blowing, and then warehouses, encroached. Left is Roque's map of 1746, and right an

1814 map of part of the estate sold after the death of City magnate

William Strode (far right: Hogarth's 1730s picture of the family is in the Tate -

details here.)

By

the 18th century the area had acquired a

reputation for wild behaviour. John Walsh's collection of dance tunes,

published in the 1730s, includes a 'Goodman's Fields Hornpipe' [left].

By

the 18th century the area had acquired a

reputation for wild behaviour. John Walsh's collection of dance tunes,

published in the 1730s, includes a 'Goodman's Fields Hornpipe' [left].  But

there were protests. A 'general meeting' in 1729 in the Hoop and Grapes alleged

that being

so near several publick Offices, and the Thames, where so much Business

is negotiated, and carried on for the support of Trade and Navigation,

will draw away Tradesmen's servants and others from their lawful

Calling, and corrupt their Manners, and also occasion great numbers of

loose, idle and disorderly Persons, as Street-Robbers and Common

Night-Walkers, so to infest the streets, that it will be very

dangerous for His Majesty's subjects to pass the same.

Arthur Bedford, chaplain of Hoxton Hospital and Sunday afternoon

preacher at St Botolph Aldgate, inveighed against the project from the

pulpit. He cited a line from the play Gibraltar:

'Whores are dog-cheap here in London. For a man may slip into the

play-house Passage, and pick up half-a-dozen for half-a-crown'. Odell

was forced out, and handed over management to the audacious Henry

Giffard.

But

there were protests. A 'general meeting' in 1729 in the Hoop and Grapes alleged

that being

so near several publick Offices, and the Thames, where so much Business

is negotiated, and carried on for the support of Trade and Navigation,

will draw away Tradesmen's servants and others from their lawful

Calling, and corrupt their Manners, and also occasion great numbers of

loose, idle and disorderly Persons, as Street-Robbers and Common

Night-Walkers, so to infest the streets, that it will be very

dangerous for His Majesty's subjects to pass the same.

Arthur Bedford, chaplain of Hoxton Hospital and Sunday afternoon

preacher at St Botolph Aldgate, inveighed against the project from the

pulpit. He cited a line from the play Gibraltar:

'Whores are dog-cheap here in London. For a man may slip into the

play-house Passage, and pick up half-a-dozen for half-a-crown'. Odell

was forced out, and handed over management to the audacious Henry

Giffard.

The same year

the actor-manager David

Garrick made his successful début as Richard

III [playbill left, plus William Hogarth's 1745 picture of him in this rôle]. As Benjamin Victor wrote, Coaches

and chariots with coronets soon surrounded that remote playhouse

(History of the Theatres

of London and Dublin 1761). The

final production,The Beggar's Opera [right],

was in 1742. Four years later it

was pulled down; a further building on the site briefly showed other

forms of entertainment, but was converted into a warehouse and burned

down in 1809.

The same year

the actor-manager David

Garrick made his successful début as Richard

III [playbill left, plus William Hogarth's 1745 picture of him in this rôle]. As Benjamin Victor wrote, Coaches

and chariots with coronets soon surrounded that remote playhouse

(History of the Theatres

of London and Dublin 1761). The

final production,The Beggar's Opera [right],

was in 1742. Four years later it

was pulled down; a further building on the site briefly showed other

forms of entertainment, but was converted into a warehouse and burned

down in 1809.  A local businessman/playwright who crossed swords with Garrick - though

to his credit later secretly championed him in a conflict with Kenrick

- was Joseph Reed (1723-87).

Born in Stockton-on-Tees, where his father was a rope-maker, he

continued this trade when he settled in Sun Tavern Fields in 1757. It

funded his literary activities, which began with a 'mock tragedy' of

1758, Madrigal and Trulletta [right], performed at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden 'under the direction of Mr Cibber', which occasioned a riposte to the criticism of Tobias Smollett, A Sop in the Pan for a physical critick, in a letter to Dr. Sm*ll*t, by a Halter-maker. This was followed by The Register Office in 1761. His 1767 version of Dido

was the cause of his clash with Garrick: it played for three nights

only, and was only later published. More successful was his comic opera

version of Tom Jones two years later, also performed at the Theatre Royal. He also published The Tradesman's Companion, or Tables of Avordupois Weight, a treatise on the monopoly of hemp, and a humorous account of his own life. He was buried at Bunhill Fields cemetery.

A local businessman/playwright who crossed swords with Garrick - though

to his credit later secretly championed him in a conflict with Kenrick

- was Joseph Reed (1723-87).

Born in Stockton-on-Tees, where his father was a rope-maker, he

continued this trade when he settled in Sun Tavern Fields in 1757. It

funded his literary activities, which began with a 'mock tragedy' of

1758, Madrigal and Trulletta [right], performed at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden 'under the direction of Mr Cibber', which occasioned a riposte to the criticism of Tobias Smollett, A Sop in the Pan for a physical critick, in a letter to Dr. Sm*ll*t, by a Halter-maker. This was followed by The Register Office in 1761. His 1767 version of Dido

was the cause of his clash with Garrick: it played for three nights

only, and was only later published. More successful was his comic opera

version of Tom Jones two years later, also performed at the Theatre Royal. He also published The Tradesman's Companion, or Tables of Avordupois Weight, a treatise on the monopoly of hemp, and a humorous account of his own life. He was buried at Bunhill Fields cemetery. | At the New Wells, the bottom of Lemon-street [sic], Goodman's fields, this evening will be perform'd several new exercises of rope-dancing, tumbling, vaulting, and equilibres [= balancing acts]. Rope-dancing by Mons. Magito, Mons. Janno; and Madem. de Lisle will perform several equilibres on the slack rope. And variety of tumbling by the celebrated Mr. Towers, the English tumbler, Mons. Guitat, Mons. Janno, and Mr. Hough. Singing my Miss Karver, and dancing (both serious and comic) by Mr. Carney, Mr. Shawford, Madem. Renos, Madem. Duval, and Mrs. Hough. With several new equilibres by the famous Little Russia Boy, who performs several balances upon the top of a ladder eight foot high; and then comes down, head foremost, through the rounds of the ladder; he also performs all the balances on the chairs, and several others never yet perform'd, which no one can do in England but himself. To which will be added, a great scene after the manner of the Ridotto al' Fresco. The whole to conclude wih a grand represenation of Water Works, as in the Doge's Gardens at Venice. The scenes, cloaths, and musick, all new. The scenes painted by Mons. Deroto. To begin every evening exactly at half an hour after five. |

John

Strype, whose 1720 Survey

of London updated Stow, describes the

area as chiefly inhabited by thriving Jews. From 1748 there was

a Portuguese Jews hospital in Leman Street - it moved to Mile End

Old Town in 1792.

John

Strype, whose 1720 Survey

of London updated Stow, describes the

area as chiefly inhabited by thriving Jews. From 1748 there was

a Portuguese Jews hospital in Leman Street - it moved to Mile End

Old Town in 1792. | .....We make a small excursion into Mansell Street, which is quiet. All about here, and in Great Ailie [sic] Street, Tenter Street, and their vicinities, the houses are old, large, of the very shabbiest-genteel aspect, and with a great appearance of being snobbishly ashamed of the odd trades to which many of their rooms are devoted. Shirt-making in buried basements, packing-case, or, perhaps, cardboard box-making, on the ground-floor; and glimpses of very dirty bald heads, bending over cobbling, or the sorting of "old clo'," through the cracked and rag-stuffed upper windows. Jewish names - Isaacs, Levy, Israel, Jacobs, Rubinsky, Moses, Aaron - wherever names appear, and frequent inscriptions in the homologous letters of Hebrew. Many of these inscriptions are on the windows of eating-houses, whose interior mysteries are hidden by muslin curtains; and we occasionally find a shop full of Hebrew books, and showing in its window remarkable little nick-nacks appertaining to synagogue worship, amid plaited tapers of various colours. |

The artist David Garshen Bomberg

(1890-1957), a member of the group of local Jewish artists and writers

which later came to be known as the 'Whitechapel Boys' (Isaac Rosenberg

and Mark Gertler were two other members), made this drawing [left] in chalk on

paper of his sister Raie (1897- c1921), according to their younger

sister in about 1910 when he was still living at the family home at 20 Tenter Buildings, St

Mark's Street.

The artist David Garshen Bomberg

(1890-1957), a member of the group of local Jewish artists and writers

which later came to be known as the 'Whitechapel Boys' (Isaac Rosenberg

and Mark Gertler were two other members), made this drawing [left] in chalk on

paper of his sister Raie (1897- c1921), according to their younger

sister in about 1910 when he was still living at the family home at 20 Tenter Buildings, St

Mark's Street.

Bomberg was was born in Birmingham, the son of Abraham, a Polish

leather-worker; they moved to the East End in 1885 (where he attended

Castle Street School, unlike his siblings who went to the Jewish Free

School), which opened for him the world of Jewish theatre and culture

which inspired much of his early art. His mother Rebecca died in 1912

at the age of 48, when he was studying at the Slade; she had supported

his career, including helping him set up a studio next door, and the

loss hit him hard. It inspired two drawings of 1913 entitled 'Family

Bereavement' [right] - and he moved away from home. (The first and third of these pictures are in the Tate Gallery.)

Bomberg was was born in Birmingham, the son of Abraham, a Polish

leather-worker; they moved to the East End in 1885 (where he attended

Castle Street School, unlike his siblings who went to the Jewish Free

School), which opened for him the world of Jewish theatre and culture

which inspired much of his early art. His mother Rebecca died in 1912

at the age of 48, when he was studying at the Slade; she had supported

his career, including helping him set up a studio next door, and the

loss hit him hard. It inspired two drawings of 1913 entitled 'Family

Bereavement' [right] - and he moved away from home. (The first and third of these pictures are in the Tate Gallery.) From the 17th century, boggy

land had been drained for tenter grounds, with frames (tenters) for drying

washed woven cloth: hence Tenter Street, and the expression 'to be on

tenterhooks'. There were other Tenter Streets and Grounds - including

the one in Spitalfields which in time became the centre of the Dutch Jewish

community (the Sasieni family website gives an excellent account). In past times there was a meat market between Red Lion Street and

Minories, and a thrice-weekly hay and straw market until 1928. But by 1678, the land was

beginning to to be sold off for the construction of housing, and this process continued apace. As explained here,

by 1829 there was a roadway around the site which became North, South, East and West Tenter Streets, and it became criss-crossed

with small streets and houses, including St Mark's Street [originally Mark Street], Newnham Street and Scarborough

Street.

From the 17th century, boggy

land had been drained for tenter grounds, with frames (tenters) for drying

washed woven cloth: hence Tenter Street, and the expression 'to be on

tenterhooks'. There were other Tenter Streets and Grounds - including

the one in Spitalfields which in time became the centre of the Dutch Jewish

community (the Sasieni family website gives an excellent account). In past times there was a meat market between Red Lion Street and

Minories, and a thrice-weekly hay and straw market until 1928. But by 1678, the land was

beginning to to be sold off for the construction of housing, and this process continued apace. As explained here,

by 1829 there was a roadway around the site which became North, South, East and West Tenter Streets, and it became criss-crossed

with small streets and houses, including St Mark's Street [originally Mark Street], Newnham Street and Scarborough

Street.  Left is the 1894 Ordnance Survey map of the area. As

explained above, and on the St Mark Whitechapel page, it became an impoverished - but vibrant - Jewish quarter, as the following 1921

street directory of shopkeepers and other premises in St Mark's Street

shows. (The synagogue in Scarborough Street had moved to Mansell Street in the 1870s.) According to an article in the Jewish Chronicle in 1920, around the feast of Purim

(based on the story of Esther, when various kinds of mischief-making by

children was part of the ritual, including stamping and booing at the

mention of the villain Haman) children in these streets were hawking

'Haman toffee' at inflated prices - impressing the reporter with their

enterprise!

Left is the 1894 Ordnance Survey map of the area. As

explained above, and on the St Mark Whitechapel page, it became an impoverished - but vibrant - Jewish quarter, as the following 1921

street directory of shopkeepers and other premises in St Mark's Street

shows. (The synagogue in Scarborough Street had moved to Mansell Street in the 1870s.) According to an article in the Jewish Chronicle in 1920, around the feast of Purim

(based on the story of Esther, when various kinds of mischief-making by

children was part of the ritual, including stamping and booing at the

mention of the villain Haman) children in these streets were hawking

'Haman toffee' at inflated prices - impressing the reporter with their

enterprise! |

St Mark's Street - South Side

7 Morris Borenheim, hairdresser 9 Mrs Hetty Goldstone, coffee rooms 11 Joseph Assenheim, ice cream maker 15 Miss Annie Jones, dairy 21 Joseph Jackson, french polisher 25 Jacob Davis, greengrocer St Marks Church 29 Rev Lionel Smithett Lewis MA (Vicarage) 31 Joseph Levy, chandlers shop 33 Mrs Ada Cohen, baker 35 Scarborough Arms, Mrs Mary Weinberg [pictured above] ... here is Scarborough Street ... 45 Federation of Synagogues Burial Society 47 Alec Golding, tailor ... here is Tenter Street South ... |

North Side

4 Nathan Renkachinsky, boot repairer 6 Mrs Minnie Ginzburg, greengrocer  8 Lazarus Cooper, chandlers shop [premises right in 1977] 8 Lazarus Cooper, chandlers shop [premises right in 1977]... here is Tenter Street north ... 10 Hyman Indick, tobacconist [1] 26 George Rosenfeld, furrier 34 Mrs Betsy Carter, chandlers shop ... here is Scarborough Street ... ... here is Tenter Street South ... [1] born Russia c1879; his wife Fanny died 1922, he died 1955 |

The Blitz took its toll [left is South Tenter Street, looking west, after 1940 bomb damage], and in St Mark's Street only the Scarborough Arms (closed 2010) of 1855 [right, with a bollard in Scarborough Street] and two houses at 31-33 remain: the other housing is of the 1970s and 1980s, now with English Martyrs primary school (1969) on the right, where the bomb fell. As the 1967 picture of Scarborough Street [far right] shows, there were prefabs on this site for some years after the war. Geoffrey Fletcher's London (Hutchinson 1968) comments condescendingly Stand

at the door of the Scarborough Arms, and survey the typical

mid-nineteenth-century artisans' dwellings in Scarborough Street — two

storey in red and yellow brick, with round headed windows and doors —

and take in the prefabs on the spare ground opposite, which impart a

pleasingly mournful 1947 quality to the composition. In fact despite their temporary nature prefabs were generally popular homes, and proved more durable than expected.

The Blitz took its toll [left is South Tenter Street, looking west, after 1940 bomb damage], and in St Mark's Street only the Scarborough Arms (closed 2010) of 1855 [right, with a bollard in Scarborough Street] and two houses at 31-33 remain: the other housing is of the 1970s and 1980s, now with English Martyrs primary school (1969) on the right, where the bomb fell. As the 1967 picture of Scarborough Street [far right] shows, there were prefabs on this site for some years after the war. Geoffrey Fletcher's London (Hutchinson 1968) comments condescendingly Stand

at the door of the Scarborough Arms, and survey the typical

mid-nineteenth-century artisans' dwellings in Scarborough Street — two

storey in red and yellow brick, with round headed windows and doors —

and take in the prefabs on the spare ground opposite, which impart a

pleasingly mournful 1947 quality to the composition. In fact despite their temporary nature prefabs were generally popular homes, and proved more durable than expected.

Newnham Street

figures as a 'Ripper site' - Albert Bachert lived at Gordon House, and

there are many web references. It also provides the setting of a

semi-autobiographical novel by Yoel Sheridan [right], who grew up in the street and now lives in Israel, and whom we thank for his contact: From Here to Obscurity (Tenterbooks

2001) gives a vivid account of the life of the Yiddish-speaking

community in and around this street in the Hitler years 1933-45, and

includes material about the evacuation of pupils from the Jews' Free

School

(JFS) to communities in the Fens (the Junior and Senior departments to

the city of Ely and the Central School to the villages of Soham,

Isleham and Fordham), on which the Ely Standard [right] commented when the book was published.

Newnham Street

figures as a 'Ripper site' - Albert Bachert lived at Gordon House, and

there are many web references. It also provides the setting of a

semi-autobiographical novel by Yoel Sheridan [right], who grew up in the street and now lives in Israel, and whom we thank for his contact: From Here to Obscurity (Tenterbooks

2001) gives a vivid account of the life of the Yiddish-speaking

community in and around this street in the Hitler years 1933-45, and

includes material about the evacuation of pupils from the Jews' Free

School

(JFS) to communities in the Fens (the Junior and Senior departments to

the city of Ely and the Central School to the villages of Soham,

Isleham and Fordham), on which the Ely Standard [right] commented when the book was published.

Left is Moses Brothers' Warehouse (c1888 by Dunk & Geden) at 18 North

Tenter Street in 1977 and after conversion to flats in 1995; and two 18th century houses

opposite. Right is

4-6a (1977) and 13-29 North Tenter Street (looking west) in 1967, and 5

St Mark's Street at the corner of North Tenter Street in 1975, all now

demolished.

Left is Moses Brothers' Warehouse (c1888 by Dunk & Geden) at 18 North

Tenter Street in 1977 and after conversion to flats in 1995; and two 18th century houses

opposite. Right is

4-6a (1977) and 13-29 North Tenter Street (looking west) in 1967, and 5

St Mark's Street at the corner of North Tenter Street in 1975, all now

demolished.

Moses Brothers also built 29-31 West Tenter

Street, a clothing warehouse by Tenter Passage, designed in 1899 by Dunk and Bousfield - left 1977, and after conversion to offices in 1988 (linked to 58 Mansell Street behind); 25-27 (also 1977) were demolished. Rght are houses in this street, and the last building to be demolished in the 1990 excavation.

Moses Brothers also built 29-31 West Tenter

Street, a clothing warehouse by Tenter Passage, designed in 1899 by Dunk and Bousfield - left 1977, and after conversion to offices in 1988 (linked to 58 Mansell Street behind); 25-27 (also 1977) were demolished. Rght are houses in this street, and the last building to be demolished in the 1990 excavation.

Right are two views of tenements in East Tenter Street, back to back with those on Leman street, speculatively built c1900 by N & R Davis, with

attic workrooms - perhaps with Jewish tenants in view? - and the exterior and interior of the adjacent warehouse, now offices.

Right are two views of tenements in East Tenter Street, back to back with those on Leman street, speculatively built c1900 by N & R Davis, with

attic workrooms - perhaps with Jewish tenants in view? - and the exterior and interior of the adjacent warehouse, now offices.

Variously

shown on old maps as Ayliffe, Aylie and Alie Streets, often divided

between 'Great' / 'Little' (west / east of Leman Street), little

remains of its history, for instance as the location of several

dissenting chapels (see here), though on the eastern side the German Lutheran Church

and school remain. On the western side, at nos. 30-44, is a terrace of houses of c1720 (much altered), some with ground-floor shop

extensions out to the street [left], mostly modern but the one at 32 is Victorian. 34 has a carved doorcase (noted by Summerson in Georgian London).

Across the road, opposite the north end of St Mark's Street (originally

Alie Place, with houses of c1820 on the corner), is Half Moon Passage [right in 1981 and today], an alley between a symmetrical pair of 18th century houses [now offices] at nos.17-19 leading to Braham Street. The Half Moon

Theatre Company

began life in a former synagogue at no.27, before moving in 1979 to a

former Methodist chapel on the Mile End Road (now closed, though their

work with young people continues). See here for 'The Hutch' - the Jewish Working Men's Club and Lads' Institute, and headquarters of the Jewish Lads' and Girls' Brigades.

Variously

shown on old maps as Ayliffe, Aylie and Alie Streets, often divided

between 'Great' / 'Little' (west / east of Leman Street), little

remains of its history, for instance as the location of several

dissenting chapels (see here), though on the eastern side the German Lutheran Church

and school remain. On the western side, at nos. 30-44, is a terrace of houses of c1720 (much altered), some with ground-floor shop

extensions out to the street [left], mostly modern but the one at 32 is Victorian. 34 has a carved doorcase (noted by Summerson in Georgian London).

Across the road, opposite the north end of St Mark's Street (originally

Alie Place, with houses of c1820 on the corner), is Half Moon Passage [right in 1981 and today], an alley between a symmetrical pair of 18th century houses [now offices] at nos.17-19 leading to Braham Street. The Half Moon

Theatre Company

began life in a former synagogue at no.27, before moving in 1979 to a

former Methodist chapel on the Mile End Road (now closed, though their

work with young people continues). See here for 'The Hutch' - the Jewish Working Men's Club and Lads' Institute, and headquarters of the Jewish Lads' and Girls' Brigades.

The group of buildings from nos. 21-29 [left in 1973] show

how the street has changed. The early 19th century White Swan public

house, at no.21, with its curved window and fancy lamp bracket, is

still here -

now with an extension into no.23. The small building at

no.25 had been Miss Lily Gray's wholesale grocer's shop (also at 19 Prescot

Street) until she went bankrupt in 1938. Later it became Mrs Millie

Ginsberg's Dining Rooms - 'Tea Always Ready', read the sign. By 1981 it

was occupied by Khan and Sons [right]. Nos. 23-25 were demolished and replaced by a 4-storey office building, with 5-storey flats (nos.29-47) to their right.

The group of buildings from nos. 21-29 [left in 1973] show

how the street has changed. The early 19th century White Swan public

house, at no.21, with its curved window and fancy lamp bracket, is

still here -

now with an extension into no.23. The small building at

no.25 had been Miss Lily Gray's wholesale grocer's shop (also at 19 Prescot

Street) until she went bankrupt in 1938. Later it became Mrs Millie

Ginsberg's Dining Rooms - 'Tea Always Ready', read the sign. By 1981 it

was occupied by Khan and Sons [right]. Nos. 23-25 were demolished and replaced by a 4-storey office building, with 5-storey flats (nos.29-47) to their right.

Left is 28 Alie Street, at the northern end of St Mark's Street, in 1975. Right

are the impressive premises of Hammer, Theelen & Co on the corner

of Alie and Mansell Streets, in 1977. 'Ellenberg, Hammer & Co', the

partnership of Francis Siegfried Ellenberg, Sevrin Theelen and Carl

Erich Hammer, general merchants

of Great Winchester Street in London and Broadway in New York, was

dissolved in 1909, continuing as separate companies on both sides of

the Atlantic. Hammer, Theelen & Co were trading from Lawrence Lane

in Cheapside in 1913 as Japanese silk merchants, but

also involved with other products, including the 'Landophone', a device

to enable chauffeurs to communicate with their passengers in traffic. The Auto for 1913, commented that speaking tubes were potentially hazardous and none too cleanly, and that electric telephones were not much louder:

Left is 28 Alie Street, at the northern end of St Mark's Street, in 1975. Right

are the impressive premises of Hammer, Theelen & Co on the corner

of Alie and Mansell Streets, in 1977. 'Ellenberg, Hammer & Co', the

partnership of Francis Siegfried Ellenberg, Sevrin Theelen and Carl

Erich Hammer, general merchants

of Great Winchester Street in London and Broadway in New York, was

dissolved in 1909, continuing as separate companies on both sides of

the Atlantic. Hammer, Theelen & Co were trading from Lawrence Lane

in Cheapside in 1913 as Japanese silk merchants, but

also involved with other products, including the 'Landophone', a device

to enable chauffeurs to communicate with their passengers in traffic. The Auto for 1913, commented that speaking tubes were potentially hazardous and none too cleanly, and that electric telephones were not much louder:  If, therefore,

the sound at the receiver could be intensified, the electric telephone

would be much the best way of speaking to the driver ... All that [the Landophone]

really is, is an extra powerful telephone, consisting of an ordinary

transmitter, an intensifying induction coil, a megaphone-like receiver

and a battery of accumulators. The receiver hangs on a hook mounted

inside the car and is held by a spring clip; the receiver is fixed near

the driver to some convenient part of the car, such as the steering

column, or even on the dash. The intensifying coil with the necessary

terminals, is contained in a neat, polished wood box so that should it

to be exposed to view it does not spoil the appearance of the car. To

obtain the best results a battery of eight volts should be employed. A

complete 'Landophone' set, without the accumulators, is sold at the

price of £4 15s. and the finish and appearance are good in every way. If, therefore,

the sound at the receiver could be intensified, the electric telephone

would be much the best way of speaking to the driver ... All that [the Landophone]

really is, is an extra powerful telephone, consisting of an ordinary

transmitter, an intensifying induction coil, a megaphone-like receiver

and a battery of accumulators. The receiver hangs on a hook mounted

inside the car and is held by a spring clip; the receiver is fixed near

the driver to some convenient part of the car, such as the steering

column, or even on the dash. The intensifying coil with the necessary

terminals, is contained in a neat, polished wood box so that should it

to be exposed to view it does not spoil the appearance of the car. To

obtain the best results a battery of eight volts should be employed. A

complete 'Landophone' set, without the accumulators, is sold at the

price of £4 15s. and the finish and appearance are good in every way. |

Here

are some further contrasts. Left are

pictures from 1930-49....

Here

are some further contrasts. Left are

pictures from 1930-49....

... and here are scenes of

dereliction in the 1980s (including Shaffer Ltd. at no.33 and 'British

Smoked Salmon'); right today are flats at 14-20, and at the end of the road the office

blocks on the opposite corners - no.1, and 55 Mansell Street (including

RBS).

... and here are scenes of

dereliction in the 1980s (including Shaffer Ltd. at no.33 and 'British

Smoked Salmon'); right today are flats at 14-20, and at the end of the road the office

blocks on the opposite corners - no.1, and 55 Mansell Street (including

RBS).

On

the east side of the street, beyond the German chapel, planning

permission was given to Barratt's in 2007 for a 27-storey tower block

(235 flats plus retail units) - their tallest East London project

to

date - and an adjacent 7-storey commercial block on the site of former

factory at nos.61-75, with completion originally envisaged by 2012. Left is the derelict site, and visualisations of the future.

On

the east side of the street, beyond the German chapel, planning

permission was given to Barratt's in 2007 for a 27-storey tower block

(235 flats plus retail units) - their tallest East London project

to

date - and an adjacent 7-storey commercial block on the site of former

factory at nos.61-75, with completion originally envisaged by 2012. Left is the derelict site, and visualisations of the future.

...in the north-west corner of the parish is the Hoop and Grapes at 47 Aldgate High Street (nearly opposite Aldgate tube

station). Allegedly the oldest licensed house in the City, parts of it

were built in 1593, over much older cellars. Originally called The

Castle, then the Angel & Crown, then Christopher Hills, it took its

present name (referring to the sale of both beer and wine) in the

1920s. It is one of three timber-framed

buildings (the one on the right was refaced in the 18th century) to

survive the Fire of London, which stopped 50 yards away. It has been

much-restored since this 1950s picture. More details and images here

...in the north-west corner of the parish is the Hoop and Grapes at 47 Aldgate High Street (nearly opposite Aldgate tube

station). Allegedly the oldest licensed house in the City, parts of it

were built in 1593, over much older cellars. Originally called The

Castle, then the Angel & Crown, then Christopher Hills, it took its

present name (referring to the sale of both beer and wine) in the

1920s. It is one of three timber-framed

buildings (the one on the right was refaced in the 18th century) to

survive the Fire of London, which stopped 50 yards away. It has been

much-restored since this 1950s picture. More details and images here