§ Berner Street: 1871, disused by the 1920s; now the site of Bernhard Baron House

[street renamed Henriques Street 1961] - Harry Gosling School was built opposite in 1909 - the site of both schools is shown on Goad's 1899 insurance map, right. Here

is a paper on 'Scientific Method in Board Schools' delivered in the

school in 1895. In July 1892 Mrs Louisa Hopkins, chair of a Massachusetts commission

appointed to investigate manual training and industrial education,

visited this, among many other, schools. Note her comments on the

implications of being a Jewish-majority school: § Berner Street: 1871, disused by the 1920s; now the site of Bernhard Baron House

[street renamed Henriques Street 1961] - Harry Gosling School was built opposite in 1909 - the site of both schools is shown on Goad's 1899 insurance map, right. Here

is a paper on 'Scientific Method in Board Schools' delivered in the

school in 1895. In July 1892 Mrs Louisa Hopkins, chair of a Massachusetts commission

appointed to investigate manual training and industrial education,

visited this, among many other, schools. Note her comments on the

implications of being a Jewish-majority school:

...We first called at the St. [sic]

Berner Street Board School, on the spot where the opium joint described

in 'Edwin Drood' stood [she seems to be confusing this with the other

local school she visited, St George's Street].

We visited first the old school building, which was an old rice mill;

the tall mill still stood there; the ground floor is now used as a

storeroom. I saw a cart loading up with apparatus for drawing tables

and large T-squares. We went up stairs and visited the cookery class of

Jewish girls; the teacher was giving a demonstration lesson on a fruit

pie; only a gas stove was in use. After this part of the lesson, which

took one hour, the class was divided, one-half attending the

demonstration lesson and the other half writing it for an hour, and the

next hour vice versa ; the lesson was three hours long, — each child

has sixty lessons. The girls are eleven and twelve years old. The

laundry room we next visited was large, with closets, boiler, tubs,

ironing tables and stove with flat irons. A similar class to the

cooking class was receiving a lesson from the black-board in washing

cretonnes and colored cloths. After this I saw the girls washing at the

tubs, one tub being fltted for washing colored articles, and the other

for white silk scarfs or handkerchiefs which the girls had brought from

home. I saw some of their laundered work also, cuffs and collars, —

very good; the girls evidently enjoyed the work very much.

We then went to the new school-house near by, — Berner Street School.

It was a fine large building, with well-lighted rooms, sliding

partitions largely of glass, big halls and play-grounds for boys on the

top of the building. We visited a sloyd class [a handicaraft-based education system originating in Finland, popular in the USA at this time] taught

by the son of the head master; it showed very good work for the first

year, — in operation only since the previous October. They used knife,

plane, saw, etc....

The pupils of the school are nearly all Jews, Russian or Polish, some

German, who the master said were much the most intelligent. All have to

be taught the English language, and much the same means are used as in

the Eliot School, — in fact, when I described that way, the master said

it was exactly his way, and he thought he had invented it. However, I

saw the boys spelling small words on the black-board in an

old-fashioned way, without knowing what they meant or how to use them ;

then they learn to use a book and write words, and up in the higher

grade to read fairly well. This was not in accordance with the method

described.

All through the school were pictures, cabinets of science objects,

collected by pupils and teachers with some help from a school fund. One

teacher showed me her schedule of object lessons, — much like ours in

the lower grades. Sewing is part of the girls' work. The boys come for

extra time in sloyd. The

master complained that as soon as the boys got up a little way many

left to go to a Jewish school which gave them some advantages and was

privately endowed, or else they went to America. Some of the teachers

were Jewish; the teacher of the upper class was selected in order to

conduct their religious exercises suitably. The cookery classes also

have special provision for meeting the Jewish code with regard to food.

|

|

Blakesley

Street

[between Watney Street and Sutton Street, south of Commercial

Road]: serving the most concentrated area of poverty (apart from

St George's Street School), and

becoming predominantly Jewish: a 1910 inspection noted the difficulties attending instruction with a large foreign intake, but reported praiseworthy regularity in attendance and

full interest in work. See here for memories of a Blakesley Street resident. The site is now occupied by Fitzgerald House, a care home for the elderly; see below for the replacement school.

|

Lower Chapman Street [now Bigland Street] - [left on Goad's 1899 insurance map; right, from front and rear, and today]:one

of Robson's earliest, and one of the few of his to survive (with an

example of a double staircase separating boys from girls). Robson

added a cookery centre - a pioneering example of provision for

practical and vocational training. Its catchment area

included parts of Wapping, though two Board schools were also built

there. [After closure, it had a variety of uses, including the

University of Greenwich's School of Earth Sciences (as 'Walburgh

House') before becoming Darul Ummah

Community Centre. The London Borough of Tower Hamlets supported their

plans for its demolition and an eight-storey replacement with three

basement levels to include a mosque, funeral facilities, a gym and a

café as well as the current boys' school. But in 2010 English Heritage,

at the instigation of the Victorian Society, listed the building (Grade

II) and revised plans are being produced.] Lower Chapman Street [now Bigland Street] - [left on Goad's 1899 insurance map; right, from front and rear, and today]:one

of Robson's earliest, and one of the few of his to survive (with an

example of a double staircase separating boys from girls). Robson

added a cookery centre - a pioneering example of provision for

practical and vocational training. Its catchment area

included parts of Wapping, though two Board schools were also built

there. [After closure, it had a variety of uses, including the

University of Greenwich's School of Earth Sciences (as 'Walburgh

House') before becoming Darul Ummah

Community Centre. The London Borough of Tower Hamlets supported their

plans for its demolition and an eight-storey replacement with three

basement levels to include a mosque, funeral facilities, a gym and a

café as well as the current boys' school. But in 2010 English Heritage,

at the instigation of the Victorian Society, listed the building (Grade

II) and revised plans are being produced.]

|

Betts Street: 1884, the first 3-storey

school with halls for

all three departments - places for 300 boys, 300 girls, and 386 infants. Its opening led to the closure of the railway

arches school: despite excellent reports for 1881, the boys section was

closed in 1883 and the girls and infants in 1884-85 and the premises

declared unfit (though the authorities were happy to use them for a

time until the new school was ready). H.C. Dimsdale, Rector of Christ

Church Watney Street 1892-1909, admitting that the old premises perhaps were

quaint, somewhat jealously described the new school as palatial....replete with all the

luxuries that art and faddism can supply. This school also became predominantly Jewish. See here for pictures, and more about this street.

In the run-up to the 1909 municipal elections, the Daily News

ran a mischievous campaign accusing council schools of neglecting their

duty to feed the poor, focusing on Glengall Road School on the Isle of

Dogs (which later had a pioneering music and drama teacher, Charles

Thomas Smith). Sir John McDougall, chairman of the London County

Council, visited the school and asked those who are hungry and have had no breakfast to hold up their hands. Four out of the five were deemed not necessitous; the fifth had been given money by one Mr Crooks, who stated that but for your generosity my boy would have had to live and learn on promises... In

fact take-up was low, and arrangements had been made to feed needy

children elsewhere. But children's care committees were provided with

circulars for distribution to parents; the Betts Street committee

declined to do so.

|

§ Cable Street: 1898 - smaller, for 'only' 400

children [two early class photos right]:

built on the site of a former sugar refinery, it bears a plaque 'Cable Street Schools' but has had various names and uses in its time, as maps

of the area bear witness. (Some show it as

'Nathaniel Heckford School': Nathaniel Heckford

was a paediatrician who founded the East London Hospital for Children,

near what is now Heckford Street further along The Highway). § Cable Street: 1898 - smaller, for 'only' 400

children [two early class photos right]:

built on the site of a former sugar refinery, it bears a plaque 'Cable Street Schools' but has had various names and uses in its time, as maps

of the area bear witness. (Some show it as

'Nathaniel Heckford School': Nathaniel Heckford

was a paediatrician who founded the East London Hospital for Children,

near what is now Heckford Street further along The Highway).

These 1908 photographs show: boys' drill, girls' drill, netball,

special nature study, nature study, art, mixed maths and standard VII

maths.

After the Second World War it became a

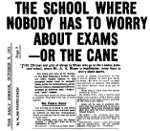

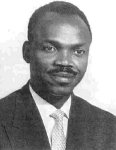

secondary modern school, St George-in-the-East Central School, with Alex Bloom as a pioneering headteacher from 1945-55 [left, with colleagues - he is second from the left at the front]. He

rejected regimentation, corporal punishment, and the use of

marks, prizes and competition, and introduced a school council [left] which

among other things voted for lunchtime ballroom dancing, and the

selling of cakes from a local bakery in the school canteen. Right is a 1951 article from the Daily Mirror about his work. On his

interesting website, Abraham Wilson, a Ghanaian pupil (who had previously attended St Paul Whitechapel and other local primaries - and is now a member of the Bahá'í faith) recalls the Bloom era: assemblies with classical music, and his stress on keeping down noise in the school (keep your foot on the soft pedal). After the Second World War it became a

secondary modern school, St George-in-the-East Central School, with Alex Bloom as a pioneering headteacher from 1945-55 [left, with colleagues - he is second from the left at the front]. He

rejected regimentation, corporal punishment, and the use of

marks, prizes and competition, and introduced a school council [left] which

among other things voted for lunchtime ballroom dancing, and the

selling of cakes from a local bakery in the school canteen. Right is a 1951 article from the Daily Mirror about his work. On his

interesting website, Abraham Wilson, a Ghanaian pupil (who had previously attended St Paul Whitechapel and other local primaries - and is now a member of the Bahá'í faith) recalls the Bloom era: assemblies with classical music, and his stress on keeping down noise in the school (keep your foot on the soft pedal).

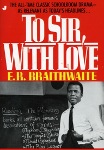

It was in Bloom's time that Edward Ricardo

Braithwaite, the Guyanan author of To

Sir with Love,

taught here. He was

an engineer who served as an RAF bomber pilot in the Second World War,

but struggled to find employment because he was black, and so trained

as a teacher. (The well-known film, starring Sidney Poitier,

was made elsewhere; Braithwaite later said of if I loathe that film from the bottom of my heart, because

it focused on the classroom rather than on the wider issues of black

recognition.) He revisted the area in 2007, for the first time in many

years, for a Radio 4 programme. He walked round St George's and read

out the sign for the crypt hall, and then tried to peep into the crypt.

His 1965 novel Choice of Straws was

adapted for Radio 4 in 2009. He was present at the 2013 Northampton

premiere of Ayub Khan-Din's well-reviewed play based on his autobiography, with Ansu

Kabia as the Braithwaite character 'Ricky' [far right] and Matthew Kelly as the

headteacher 'Florian'. It was in Bloom's time that Edward Ricardo

Braithwaite, the Guyanan author of To

Sir with Love,

taught here. He was

an engineer who served as an RAF bomber pilot in the Second World War,

but struggled to find employment because he was black, and so trained

as a teacher. (The well-known film, starring Sidney Poitier,

was made elsewhere; Braithwaite later said of if I loathe that film from the bottom of my heart, because

it focused on the classroom rather than on the wider issues of black

recognition.) He revisted the area in 2007, for the first time in many

years, for a Radio 4 programme. He walked round St George's and read

out the sign for the crypt hall, and then tried to peep into the crypt.

His 1965 novel Choice of Straws was

adapted for Radio 4 in 2009. He was present at the 2013 Northampton

premiere of Ayub Khan-Din's well-reviewed play based on his autobiography, with Ansu

Kabia as the Braithwaite character 'Ricky' [far right] and Matthew Kelly as the

headteacher 'Florian'.

The building subsequently provided accommodation for various local schools being rebuilt, and has now been

converted into 34 luxury apartments as 'Mulberry House' [right] - though

Mulberry Girls' School was only one of various temporary occupants. In 1980 the

church

exterior and adjacent

buildings featured in the gangster film The

Long Good Friday,

starring Bob Hoskins and Helen Mirren, in which Harold Shand's Rolls

Royce is blown up while his mother attends a service. The building subsequently provided accommodation for various local schools being rebuilt, and has now been

converted into 34 luxury apartments as 'Mulberry House' [right] - though

Mulberry Girls' School was only one of various temporary occupants. In 1980 the

church

exterior and adjacent

buildings featured in the gangster film The

Long Good Friday,

starring Bob Hoskins and Helen Mirren, in which Harold Shand's Rolls

Royce is blown up while his mother attends a service.

|

Christian Street: 1901

- built on the site of Martineau's sugar refinery, which at one time had

the tallest chimney in London; it was the first

local school to have a Jewish headteacher, Isaac Goldstone in 1908.

Professor Bill Fishman (b.1921) was a pupil here - here

are his childhood memories of the area. Under postwar legislation, it

was transferred to denominational control as Bishop Challoner Girls

Secondary School, which is now part of Bishop Challoner Catholic Collegiate School and Learning Village off Commercial Road; the Christian Street site [right by night before demolition] has been redeveloped for housing by Bellway Homes as SpacE1. Christian Street: 1901

- built on the site of Martineau's sugar refinery, which at one time had

the tallest chimney in London; it was the first

local school to have a Jewish headteacher, Isaac Goldstone in 1908.

Professor Bill Fishman (b.1921) was a pupil here - here

are his childhood memories of the area. Under postwar legislation, it

was transferred to denominational control as Bishop Challoner Girls

Secondary School, which is now part of Bishop Challoner Catholic Collegiate School and Learning Village off Commercial Road; the Christian Street site [right by night before demolition] has been redeveloped for housing by Bellway Homes as SpacE1.

|

St George's Street,

The

Highway (off Dellow [formerly Victoria] Street), shown right on Goad's 1887 insurance map - with two other schools beyond: regarded as a school of 'special difficulty'. See here for a spat over evening dancing classes, and here for classes in Esperanto. Mrs Louisa Hopkins, for the report noted above, also visited this school, and commented briefly: St George's Street,

The

Highway (off Dellow [formerly Victoria] Street), shown right on Goad's 1887 insurance map - with two other schools beyond: regarded as a school of 'special difficulty'. See here for a spat over evening dancing classes, and here for classes in Esperanto. Mrs Louisa Hopkins, for the report noted above, also visited this school, and commented briefly:

We went to the Highway School for girls, close to the scene of the worst White Chapel murders [does she mean 1888 Ripper victim Elizabeth Stride, linked to the nearby Swedish church and brought to the mortunary in the churchyard but killed some distance away, or the Marr murders of 1811?]

It is a fine new building, about five years old. The care-taker lives

in a house on the premises, and opens the gate to visitors; he had a

beautiful show of potted plants in bloom, with pretty shells near the

opening of the yard. All the girls were out at play, the mistresses

with them.

|

This is the more likely location for Dicken's opium den in Edwin Drood - note the comment from 1897 that the

particular den described in the story was pulled down some years ago to

make room for a Board-school playground, while the bedstead, pipes,

etc., were purchased by Americans and others interested in curious

relics.

|

§ These

schools came to cater for those classified as 'M.D.' (mentally

defective), which together with those for the partially deaf formed the

'St George's-in-the-East Group' (and from 1908 'Stepney (No.2) Group of

Special Schools').

|

In 1811 the National Society

was

founded, with the aim of establishing a church school in every

parish, and training and paying teachers for them. One of its founders

was Joshua Watson, brother of the Rector of Hackney, who retired at the

age of 43 having made a fortune in the wine trade and devoted the rest

of his life to this cause. The original name was 'The National Society

for the Promotion of

the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established

Church': its schools taught basic skills, and provided for moral and

spiritual welfare by teaching the 'national religion', in its Anglican

form. The founders' concern for the children of the

newly-industrialised cities was both philanthropic and motivated by anxiety about

social order. Astonishingly, by 1851 (anticipating state provision by

20 years) they had established 12,000 schools in England and Wales. The

National Society continues its work - our parish's honorary assistant

priest and Rector's wife, Jan Ainsworth, is its General Secretary and

Chief Education Officer of the Church of England - and celebrated its

bicentenary in 2011: see Lois Louden Distinctive and Inclusive: The National Society and Church of England Schools 1811-2011 (National Society 2012).

In our parish, the schools of St George-in-the-East (Cannon Street Road), Christ Church Watney Street, St Mark

Whitechapel, St Mary Johnson Street and St Paul Dock Street all

benefitted from its support

and funding - all but the last now gone.

In 1811 the National Society

was

founded, with the aim of establishing a church school in every

parish, and training and paying teachers for them. One of its founders

was Joshua Watson, brother of the Rector of Hackney, who retired at the

age of 43 having made a fortune in the wine trade and devoted the rest

of his life to this cause. The original name was 'The National Society

for the Promotion of

the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established

Church': its schools taught basic skills, and provided for moral and

spiritual welfare by teaching the 'national religion', in its Anglican

form. The founders' concern for the children of the

newly-industrialised cities was both philanthropic and motivated by anxiety about

social order. Astonishingly, by 1851 (anticipating state provision by

20 years) they had established 12,000 schools in England and Wales. The

National Society continues its work - our parish's honorary assistant

priest and Rector's wife, Jan Ainsworth, is its General Secretary and

Chief Education Officer of the Church of England - and celebrated its

bicentenary in 2011: see Lois Louden Distinctive and Inclusive: The National Society and Church of England Schools 1811-2011 (National Society 2012).

In our parish, the schools of St George-in-the-East (Cannon Street Road), Christ Church Watney Street, St Mark

Whitechapel, St Mary Johnson Street and St Paul Dock Street all

benefitted from its support

and funding - all but the last now gone. A shorter list of 1838, from the Minutes of the Select Committee on Education of the Poorer Classes [right] gives numbers:

A shorter list of 1838, from the Minutes of the Select Committee on Education of the Poorer Classes [right] gives numbers:  Dissenters' Charity,

Pell-street, Ratcliff-highway - 50 boys: was this the 'Tower Hamlets School' mentioned in

1815? The list of Subscription Charities & Public Societies in London

(John Murray 1823) refers to the 'Tower Hamlets Society for Clothing

and Educating Poor Children in the Protestant Religion' for which two

sermons had been preached the previous year at the parish church of St

John Wapping, though many of its benefactors were

non-Anglicans: for example, in 1810 £50 from Andrew Knies, a sugar baker of Wellclose Square (who also left money

to the German Reformed Church in the Savoy and to Robert Stodhart's chapel in

Pell Street, as well as to the Middlesex Society); in 1828 Henry Mum,

probably a member of

Zion Chapel, Whitechapel, made various educational bequests including

£100 of 3% bank annuities to the school; and in 1829 Johann George

Wicke, a member of the German chapel in Hooper Square,

left £50 to the school 'of which he is a member'. As the 1868 map [right] shows, there was a schoolhouse, marked as 'Pell Street Charity School', next to Stodhart's chapel, though according to him it was run by G.C. Smith's organisation, for 300 seamen's children.

Dissenters' Charity,

Pell-street, Ratcliff-highway - 50 boys: was this the 'Tower Hamlets School' mentioned in

1815? The list of Subscription Charities & Public Societies in London

(John Murray 1823) refers to the 'Tower Hamlets Society for Clothing

and Educating Poor Children in the Protestant Religion' for which two

sermons had been preached the previous year at the parish church of St

John Wapping, though many of its benefactors were

non-Anglicans: for example, in 1810 £50 from Andrew Knies, a sugar baker of Wellclose Square (who also left money

to the German Reformed Church in the Savoy and to Robert Stodhart's chapel in

Pell Street, as well as to the Middlesex Society); in 1828 Henry Mum,

probably a member of

Zion Chapel, Whitechapel, made various educational bequests including

£100 of 3% bank annuities to the school; and in 1829 Johann George

Wicke, a member of the German chapel in Hooper Square,

left £50 to the school 'of which he is a member'. As the 1868 map [right] shows, there was a schoolhouse, marked as 'Pell Street Charity School', next to Stodhart's chapel, though according to him it was run by G.C. Smith's organisation, for 300 seamen's children.

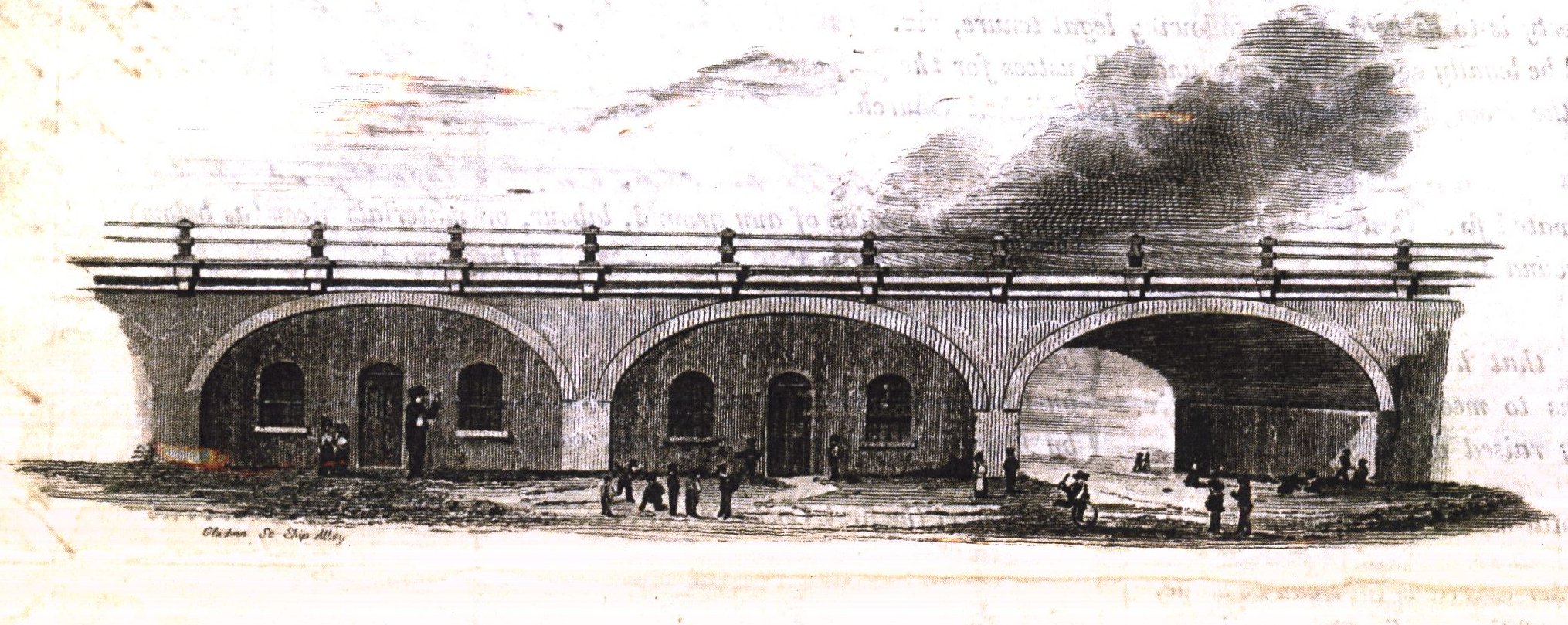

The

first major project of William Quekett, the energetic

curate of St George-in-the-East from 1830 and first incumbent of Christ

Church Watney Street, was to fit out as boys,

girls and infants schools three arches

east of Cannon Street Road, near Walburgh Street, under the

viaduct of the new London

and Blackwall Railway, which he persuaded the directors to

let on a 100-year lease for

£20

a year, reasoning that as the trains were cable-hauled from stationary

steam engines there would be no engine noise! In the event, this

system failed and conventional engines were used - see here for more details. The

drawing is from the

National

Society's archive in Bermondsey. The handwritten note says There is communication with each arch by a

door in the centre - and to warmed [sic] by an Arnotts' Stove. The 1878 Vestry map shows the location; they are shown as 'Christ Church School' on this 1868 map. [See below for the later fate of these premises.]

The

first major project of William Quekett, the energetic

curate of St George-in-the-East from 1830 and first incumbent of Christ

Church Watney Street, was to fit out as boys,

girls and infants schools three arches

east of Cannon Street Road, near Walburgh Street, under the

viaduct of the new London

and Blackwall Railway, which he persuaded the directors to

let on a 100-year lease for

£20

a year, reasoning that as the trains were cable-hauled from stationary

steam engines there would be no engine noise! In the event, this

system failed and conventional engines were used - see here for more details. The

drawing is from the

National

Society's archive in Bermondsey. The handwritten note says There is communication with each arch by a

door in the centre - and to warmed [sic] by an Arnotts' Stove. The 1878 Vestry map shows the location; they are shown as 'Christ Church School' on this 1868 map. [See below for the later fate of these premises.]  William Quekett

went on to identify a site for new schools in the eastern end of the

parish, which was to become the parish of St Mary Johnson Street. St Mary's Schools were designed by George Smith and begun in 1848, providing places for a

further 550 children. Quekett claimed he

never remembered any child from 'his' schools being in prison. When

asked Supposing a child who had

been in prison applied to one of your schools, would you admit

him? he replied Certainly

not.

William Quekett

went on to identify a site for new schools in the eastern end of the

parish, which was to become the parish of St Mary Johnson Street. St Mary's Schools were designed by George Smith and begun in 1848, providing places for a

further 550 children. Quekett claimed he

never remembered any child from 'his' schools being in prison. When

asked Supposing a child who had

been in prison applied to one of your schools, would you admit

him? he replied Certainly

not. In the newly-created parish of St Mark Whitechapel

National Schools were

established in 1841 with a schoolroom between Chamber Street and Royal

Mint Street, initially in a portion of a house and two arches under the Blackwall Railway. J. Gledhill, from Battersea Training College, was appointed the master in 1857. The boys' section was rebuilt in 1862, to

designs by John Hudson of 40 Leman Street (for which Mr John Jacobs

submitted a tender for £685 with £360 for extra classrooms, and Mr F.F.

Dudley £675 with £325 for the classrooms).

The site is shown left from

Goad's 1887 insurance maps, demonstrating how it had become hemmed in

by railway lines. From 1912 to 1921 the school was in protracted

negotiation with the

Midland Railway over windows opening onto railway property; draft

agreements were eventually produced. In the latter year a petition for

closure of the school was submitted, but this did not happen; the final

report by the LCC inspectors was in 1939, and it presumably closed

during the war. A member of our congregation remembers attending the

school. (The London Metropolitan Archives hold a series of files on

church and school matters.)

In the newly-created parish of St Mark Whitechapel

National Schools were

established in 1841 with a schoolroom between Chamber Street and Royal

Mint Street, initially in a portion of a house and two arches under the Blackwall Railway. J. Gledhill, from Battersea Training College, was appointed the master in 1857. The boys' section was rebuilt in 1862, to

designs by John Hudson of 40 Leman Street (for which Mr John Jacobs

submitted a tender for £685 with £360 for extra classrooms, and Mr F.F.

Dudley £675 with £325 for the classrooms).

The site is shown left from

Goad's 1887 insurance maps, demonstrating how it had become hemmed in

by railway lines. From 1912 to 1921 the school was in protracted

negotiation with the

Midland Railway over windows opening onto railway property; draft

agreements were eventually produced. In the latter year a petition for

closure of the school was submitted, but this did not happen; the final

report by the LCC inspectors was in 1939, and it presumably closed

during the war. A member of our congregation remembers attending the

school. (The London Metropolitan Archives hold a series of files on

church and school matters.) Some of the clergy supported this

programme; others did not, because it reduced their influence. At Christ Church Watney Street, for instance, the loss of the

railway arches schools

was a major blow - see the Rector's comments below. Its three arches are now the site of James Garden, a small community garden [right]

created and lovingly maintained by the St George's Gardens association

and other local residents in memory of James Gair. The church also

lost the attendance of the Middlesex Society scholars when, in

consequence of the Act, this School was incorporated into Raine's

Foundation - see above for both institutions - though, as explained here, as part of the

scheme £600 was provided to build a mission room adjacent to the church.

Some of the clergy supported this

programme; others did not, because it reduced their influence. At Christ Church Watney Street, for instance, the loss of the

railway arches schools

was a major blow - see the Rector's comments below. Its three arches are now the site of James Garden, a small community garden [right]

created and lovingly maintained by the St George's Gardens association

and other local residents in memory of James Gair. The church also

lost the attendance of the Middlesex Society scholars when, in

consequence of the Act, this School was incorporated into Raine's

Foundation - see above for both institutions - though, as explained here, as part of the

scheme £600 was provided to build a mission room adjacent to the church. § Berner Street: 1871, disused by the 1920s; now the site of Bernhard Baron House

[street renamed Henriques Street 1961] - Harry Gosling School was built opposite in 1909 - the site of both schools is shown on Goad's 1899 insurance map, right. Here

is a paper on 'Scientific Method in Board Schools' delivered in the

school in 1895. In July 1892 Mrs Louisa Hopkins, chair of a Massachusetts commission

appointed to investigate manual training and industrial education,

visited this, among many other, schools. Note her comments on the

implications of being a Jewish-majority school:

§ Berner Street: 1871, disused by the 1920s; now the site of Bernhard Baron House

[street renamed Henriques Street 1961] - Harry Gosling School was built opposite in 1909 - the site of both schools is shown on Goad's 1899 insurance map, right. Here

is a paper on 'Scientific Method in Board Schools' delivered in the

school in 1895. In July 1892 Mrs Louisa Hopkins, chair of a Massachusetts commission

appointed to investigate manual training and industrial education,

visited this, among many other, schools. Note her comments on the

implications of being a Jewish-majority school:

Lower Chapman Street [now Bigland Street] - [left on Goad's 1899 insurance map; right, from front and rear, and today]:one

of Robson's earliest, and one of the few of his to survive (with an

example of a double staircase separating boys from girls). Robson

added a cookery centre - a pioneering example of provision for

practical and vocational training. Its catchment area

included parts of Wapping, though two Board schools were also built

there. [After closure, it had a variety of uses, including the

University of Greenwich's School of Earth Sciences (as 'Walburgh

House') before becoming Darul Ummah

Community Centre. The London Borough of Tower Hamlets supported their

plans for its demolition and an eight-storey replacement with three

basement levels to include a mosque, funeral facilities, a gym and a

café as well as the current boys' school. But in 2010 English Heritage,

at the instigation of the Victorian Society, listed the building (Grade

II) and revised plans are being produced.]

Lower Chapman Street [now Bigland Street] - [left on Goad's 1899 insurance map; right, from front and rear, and today]:one

of Robson's earliest, and one of the few of his to survive (with an

example of a double staircase separating boys from girls). Robson

added a cookery centre - a pioneering example of provision for

practical and vocational training. Its catchment area

included parts of Wapping, though two Board schools were also built

there. [After closure, it had a variety of uses, including the

University of Greenwich's School of Earth Sciences (as 'Walburgh

House') before becoming Darul Ummah

Community Centre. The London Borough of Tower Hamlets supported their

plans for its demolition and an eight-storey replacement with three

basement levels to include a mosque, funeral facilities, a gym and a

café as well as the current boys' school. But in 2010 English Heritage,

at the instigation of the Victorian Society, listed the building (Grade

II) and revised plans are being produced.]

§ Cable Street: 1898 - smaller, for 'only' 400

children [two early class photos right]:

built on the site of a former sugar refinery, it bears a plaque 'Cable Street Schools' but has had various names and uses in its time, as maps

of the area bear witness. (Some show it as

'Nathaniel Heckford School': Nathaniel Heckford

was a paediatrician who founded the East London Hospital for Children,

near what is now Heckford Street further along The Highway).

§ Cable Street: 1898 - smaller, for 'only' 400

children [two early class photos right]:

built on the site of a former sugar refinery, it bears a plaque 'Cable Street Schools' but has had various names and uses in its time, as maps

of the area bear witness. (Some show it as

'Nathaniel Heckford School': Nathaniel Heckford

was a paediatrician who founded the East London Hospital for Children,

near what is now Heckford Street further along The Highway).

After the Second World War it became a

secondary modern school, St George-in-the-East Central School, with Alex Bloom as a pioneering headteacher from 1945-55 [left, with colleagues - he is second from the left at the front]. He

rejected regimentation, corporal punishment, and the use of

marks, prizes and competition, and introduced a school council [left] which

among other things voted for lunchtime ballroom dancing, and the

selling of cakes from a local bakery in the school canteen. Right is a 1951 article from the Daily Mirror about his work. On his

interesting website, Abraham Wilson, a Ghanaian pupil (who had previously attended St Paul Whitechapel and other local primaries - and is now a member of the Bahá'í faith) recalls the Bloom era: assemblies with classical music, and his stress on keeping down noise in the school (keep your foot on the soft pedal).

After the Second World War it became a

secondary modern school, St George-in-the-East Central School, with Alex Bloom as a pioneering headteacher from 1945-55 [left, with colleagues - he is second from the left at the front]. He

rejected regimentation, corporal punishment, and the use of

marks, prizes and competition, and introduced a school council [left] which

among other things voted for lunchtime ballroom dancing, and the

selling of cakes from a local bakery in the school canteen. Right is a 1951 article from the Daily Mirror about his work. On his

interesting website, Abraham Wilson, a Ghanaian pupil (who had previously attended St Paul Whitechapel and other local primaries - and is now a member of the Bahá'í faith) recalls the Bloom era: assemblies with classical music, and his stress on keeping down noise in the school (keep your foot on the soft pedal).

It was in Bloom's time that Edward Ricardo

Braithwaite, the Guyanan author of To

Sir with Love,

taught here. He was

an engineer who served as an RAF bomber pilot in the Second World War,

but struggled to find employment because he was black, and so trained

as a teacher. (The well-known film, starring Sidney Poitier,

was made elsewhere; Braithwaite later said of if I loathe that film from the bottom of my heart, because

it focused on the classroom rather than on the wider issues of black

recognition.) He revisted the area in 2007, for the first time in many

years, for a Radio 4 programme. He walked round St George's and read

out the sign for the crypt hall, and then tried to peep into the crypt.

His 1965 novel Choice of Straws was

adapted for Radio 4 in 2009. He was present at the 2013 Northampton

premiere of Ayub Khan-Din's well-reviewed play based on his autobiography, with Ansu

Kabia as the Braithwaite character 'Ricky' [far right] and Matthew Kelly as the

headteacher 'Florian'.

It was in Bloom's time that Edward Ricardo

Braithwaite, the Guyanan author of To

Sir with Love,

taught here. He was

an engineer who served as an RAF bomber pilot in the Second World War,

but struggled to find employment because he was black, and so trained

as a teacher. (The well-known film, starring Sidney Poitier,

was made elsewhere; Braithwaite later said of if I loathe that film from the bottom of my heart, because

it focused on the classroom rather than on the wider issues of black

recognition.) He revisted the area in 2007, for the first time in many

years, for a Radio 4 programme. He walked round St George's and read

out the sign for the crypt hall, and then tried to peep into the crypt.

His 1965 novel Choice of Straws was

adapted for Radio 4 in 2009. He was present at the 2013 Northampton

premiere of Ayub Khan-Din's well-reviewed play based on his autobiography, with Ansu

Kabia as the Braithwaite character 'Ricky' [far right] and Matthew Kelly as the

headteacher 'Florian'.

The building subsequently provided accommodation for various local schools being rebuilt, and has now been

converted into 34 luxury apartments as 'Mulberry House' [right] - though

Mulberry Girls' School was only one of various temporary occupants. In 1980 the

church

exterior and adjacent

buildings featured in the gangster film The

Long Good Friday,

starring Bob Hoskins and Helen Mirren, in which Harold Shand's Rolls

Royce is blown up while his mother attends a service.

The building subsequently provided accommodation for various local schools being rebuilt, and has now been

converted into 34 luxury apartments as 'Mulberry House' [right] - though

Mulberry Girls' School was only one of various temporary occupants. In 1980 the

church

exterior and adjacent

buildings featured in the gangster film The

Long Good Friday,

starring Bob Hoskins and Helen Mirren, in which Harold Shand's Rolls

Royce is blown up while his mother attends a service.  Christian Street: 1901

- built on the site of Martineau's sugar refinery, which at one time had

the tallest chimney in London; it was the first

local school to have a Jewish headteacher, Isaac Goldstone in 1908.

Professor Bill Fishman (b.1921) was a pupil here - here

are his childhood memories of the area. Under postwar legislation, it

was transferred to denominational control as Bishop Challoner Girls

Secondary School, which is now part of Bishop Challoner Catholic Collegiate School and Learning Village off Commercial Road; the Christian Street site [right by night before demolition] has been redeveloped for housing by Bellway Homes as SpacE1.

Christian Street: 1901

- built on the site of Martineau's sugar refinery, which at one time had

the tallest chimney in London; it was the first

local school to have a Jewish headteacher, Isaac Goldstone in 1908.

Professor Bill Fishman (b.1921) was a pupil here - here

are his childhood memories of the area. Under postwar legislation, it

was transferred to denominational control as Bishop Challoner Girls

Secondary School, which is now part of Bishop Challoner Catholic Collegiate School and Learning Village off Commercial Road; the Christian Street site [right by night before demolition] has been redeveloped for housing by Bellway Homes as SpacE1. St George's Street,

The

Highway (off Dellow [formerly Victoria] Street), shown right on Goad's 1887 insurance map - with two other schools beyond: regarded as a school of 'special difficulty'. See here for a spat over evening dancing classes, and here for classes in Esperanto. Mrs Louisa Hopkins, for the report noted above, also visited this school, and commented briefly:

St George's Street,

The

Highway (off Dellow [formerly Victoria] Street), shown right on Goad's 1887 insurance map - with two other schools beyond: regarded as a school of 'special difficulty'. See here for a spat over evening dancing classes, and here for classes in Esperanto. Mrs Louisa Hopkins, for the report noted above, also visited this school, and commented briefly: This map (from W.E. Marsden Unequal Educational Provision in East and West: The 19th Century Roots

(Psychology Press 1987) p165ff) shows how thick on the ground were the

Board Schools of the area, and how small their catchment areas, mapping

those for the first three to be built: Berner Street, Blakesley Street

and Lower Chapman Street. (It mis-locates Blakesley Street to the site

of its 1960s replacement school on Commercial Road.) The other Board

Schools above are also shown, including

Brewhouse Lane and Globe Street in Wapping. He comments The

relatively homogenous social nature of the area does not appear to have

generated a clear-cut hierarchy of elementary schools based on

differentiated fees. In 1877, for example, the two board schools then

in existence in St George's, Berner Street and Lower Chapman Street,

had fees of 1d. and 1d. or 2d. respectively. Of all the board schools

of St George's only Cable Street, small for a board school with

accommodation for 400 only, attained higher grade status. They were

conspicuous in their absence in the lists of successful London

scholarship schools.

This map (from W.E. Marsden Unequal Educational Provision in East and West: The 19th Century Roots

(Psychology Press 1987) p165ff) shows how thick on the ground were the

Board Schools of the area, and how small their catchment areas, mapping

those for the first three to be built: Berner Street, Blakesley Street

and Lower Chapman Street. (It mis-locates Blakesley Street to the site

of its 1960s replacement school on Commercial Road.) The other Board

Schools above are also shown, including

Brewhouse Lane and Globe Street in Wapping. He comments The

relatively homogenous social nature of the area does not appear to have

generated a clear-cut hierarchy of elementary schools based on

differentiated fees. In 1877, for example, the two board schools then

in existence in St George's, Berner Street and Lower Chapman Street,

had fees of 1d. and 1d. or 2d. respectively. Of all the board schools

of St George's only Cable Street, small for a board school with

accommodation for 400 only, attained higher grade status. They were

conspicuous in their absence in the lists of successful London

scholarship schools.

Harry Gosling School

was built in 1909/10. The main block was plain, but the cookery and

laundry block, designed by T.J. Bailey, is described in the current

Pevsner as charmingly detailed. Pictured left is

the school shortly after its opening, and a plaque giving the date;

Bailey's block; the boy's entrance; and the cookery and laundry doorway.

Harry Gosling School

was built in 1909/10. The main block was plain, but the cookery and

laundry block, designed by T.J. Bailey, is described in the current

Pevsner as charmingly detailed. Pictured left is

the school shortly after its opening, and a plaque giving the date;

Bailey's block; the boy's entrance; and the cookery and laundry doorway.

Right are two views from Fairclough Street today, and two views of the recent redevelopment and extension. To mark the school's centenary, in 2011 pupils produced an animation about its past and present. See here for more about the life of Harry Gosling. Edith Wyeth,

our long-serving warden who died in 2011, was school secretary,

occasional teacher and governor at the school for many years. The school

playground was the site of the discovery in 1888 of the body of

Elizabeth Stride, one of Jack the Ripper's victims - see here for more about her, and her Swedish connections.

Right are two views from Fairclough Street today, and two views of the recent redevelopment and extension. To mark the school's centenary, in 2011 pupils produced an animation about its past and present. See here for more about the life of Harry Gosling. Edith Wyeth,

our long-serving warden who died in 2011, was school secretary,

occasional teacher and governor at the school for many years. The school

playground was the site of the discovery in 1888 of the body of

Elizabeth Stride, one of Jack the Ripper's victims - see here for more about her, and her Swedish connections.

After Blakesley Street School was demolished, a new secondary school, with an entrance on Richard Street [site left - the former 196-200 Commercial Road] was built, initially known as Tower Hamlets Secondary School [images from the 1960s right, including a lesson on binary maths, the library and staffroom], then as Tower Hamlets Secondary School for Girls (with 980 pupils, aged 11-18), and now Mulberry School for Girls, with the buildings extended and upgraded. Daphne

Gould OBE was the headteacher for seventeen years (following six as deputy)

and a member of the National Curriculum Council; she gave evidence to

the 1985 Swann Report Education for All (particularly on provision of multicultural education for girls).

After Blakesley Street School was demolished, a new secondary school, with an entrance on Richard Street [site left - the former 196-200 Commercial Road] was built, initially known as Tower Hamlets Secondary School [images from the 1960s right, including a lesson on binary maths, the library and staffroom], then as Tower Hamlets Secondary School for Girls (with 980 pupils, aged 11-18), and now Mulberry School for Girls, with the buildings extended and upgraded. Daphne

Gould OBE was the headteacher for seventeen years (following six as deputy)

and a member of the National Curriculum Council; she gave evidence to

the 1985 Swann Report Education for All (particularly on provision of multicultural education for girls).