Ratcliff(e)

Highway (later St George's Street / now The Highway)

Ratcliff(e)

Highway (later St George's Street / now The Highway)

and streets off

see below for its ancient history

see below for its ancient history

In

the 18th century merchandise was brought to and from the City mainly on

the river - Commercial Road was still fields, and the lane that led

east from the Tower of London through Shadwell was narrow, though it

bore the name Ratcliff Highway [part of it was later renamed St

George's Street, and now it is known simply as The Highway]. Left is a trade card from the 1770's (from the British Museum collection). By the

turn of the 19th century The Highway had acquired a

mythological

status across London - almost certainly exaggerated - as a centre of

all kinds of criminal activity, drunkenness and wild behaviour.

A BBC2 programme The

Violent Highway (Blast

Films, first screened on 16 May 2009) chronicled its past and present,

with contributions filmed in and around the church by Baroness P.D.

James [see below], the Rector and others. Its thesis was that, despite

public perceptions, the local area is less violent now than in any

period in its history. The Highway itself is today principally a

traffic artery - allegedly the fourth busiest road in London. Here

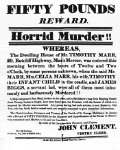

are some historic accounts, from various periods. Andy Jarosz' website has an article about the street which includes Ratcliffe Highway sung by The Dubliners. In 2013 Dr Lucy Worsley's BBC4 series 'A Very British Murder' began with an accurate account of the murders and their aftermath [right].

In

the 18th century merchandise was brought to and from the City mainly on

the river - Commercial Road was still fields, and the lane that led

east from the Tower of London through Shadwell was narrow, though it

bore the name Ratcliff Highway [part of it was later renamed St

George's Street, and now it is known simply as The Highway]. Left is a trade card from the 1770's (from the British Museum collection). By the

turn of the 19th century The Highway had acquired a

mythological

status across London - almost certainly exaggerated - as a centre of

all kinds of criminal activity, drunkenness and wild behaviour.

A BBC2 programme The

Violent Highway (Blast

Films, first screened on 16 May 2009) chronicled its past and present,

with contributions filmed in and around the church by Baroness P.D.

James [see below], the Rector and others. Its thesis was that, despite

public perceptions, the local area is less violent now than in any

period in its history. The Highway itself is today principally a

traffic artery - allegedly the fourth busiest road in London. Here

are some historic accounts, from various periods. Andy Jarosz' website has an article about the street which includes Ratcliffe Highway sung by The Dubliners. In 2013 Dr Lucy Worsley's BBC4 series 'A Very British Murder' began with an accurate account of the murders and their aftermath [right].

Jacob

Jamrach, born in Germany, had traded in animals in Antwerp, and moved

his business to London in the early 19th century. His son Johan

Christian Carl (Charles, 1815-91) took over from 1840 until his death, when he was succeeded by

his son Albert Edward [pictures right from 1896].

Seamen brought small animals, such as monkeys and parrots (on one

occasion 6,000 parakeets were kept crowded in a single room), and

larger creatures - elephants, tigers, camels, rhinos, and bears -

arrived in crates and were kept in iron cages. Jamrachs imported a

female rhinoceros for London Zoo in 1850, and another in 1872 - several

others having died in transit in the intervening years. Lord Rothschild

bought a white cougar for his museum in Tring, which was transferred to

London Zoo from 1848-52.

Jacob

Jamrach, born in Germany, had traded in animals in Antwerp, and moved

his business to London in the early 19th century. His son Johan

Christian Carl (Charles, 1815-91) took over from 1840 until his death, when he was succeeded by

his son Albert Edward [pictures right from 1896].

Seamen brought small animals, such as monkeys and parrots (on one

occasion 6,000 parakeets were kept crowded in a single room), and

larger creatures - elephants, tigers, camels, rhinos, and bears -

arrived in crates and were kept in iron cages. Jamrachs imported a

female rhinoceros for London Zoo in 1850, and another in 1872 - several

others having died in transit in the intervening years. Lord Rothschild

bought a white cougar for his museum in Tring, which was transferred to

London Zoo from 1848-52.  In 1869 the poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti bought an Australian wombat, which he called the most beautiful of God's creatures. A pair lived in his garden along with numerous other animals at Cheyne

Walk, Chelsea. When one died in 1869 he wrote I never reared

a young wombat / To glad me with his pin-hole eye, / But when he was most

sweet and fat / and tail-less he was sure to die! [his sketch left]. Jamrach offered him an elephant for £400 but he

declined. Mark Twain records they they supplied P.T. Barnum, the circus

owner, with elephants.

In 1869 the poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti bought an Australian wombat, which he called the most beautiful of God's creatures. A pair lived in his garden along with numerous other animals at Cheyne

Walk, Chelsea. When one died in 1869 he wrote I never reared

a young wombat / To glad me with his pin-hole eye, / But when he was most

sweet and fat / and tail-less he was sure to die! [his sketch left]. Jamrach offered him an elephant for £400 but he

declined. Mark Twain records they they supplied P.T. Barnum, the circus

owner, with elephants. | Extraordinary Escape of A Tiger in Ratcliff Highway: Frightful Attack of the Animal on a Boy [27 October 1857] Yesterday, between twelve and one o'clock at noon, the inhabitants of St George's-in-the-East (alias Ratcliff Highway), were suddenly thrown into a state of utmost alarm in consequence of the escape of a large tiger from the warehouse of Mr Jamrach, the extensive importer of wild beasts, &c., of No. 180, Ratcliff Highway, where by a boy, named John Wade, aged five years, was very seriously injured, and other parties' lives were placed in great jeopardy. It appears that yesterday morning Mr Jamrach received several boxes, containing two tigers, a lion, and other animals, from the steam ship Germany, lying off Hambro' Wharf, near the Custom House, Lower Thames Street, City. The packages were safely placed in a van, and conveyed to the warehouse in Betts Street, St George's-in-the-East, followed by a crowd of men, women and children, where a number of labourers adopted means to unload the vehicle. They had removed several boxes into the premises in safety, and had just lowered a large ironbound cage on to the pavement in front of the gateway, when Police Constable Stewart requested the persons standing round to keep back in case of accident.The next moment the occupant (a fine full-sized tiger) became restless, and forced out one end of the cage, when the spectators rushed in every direction from the spot in a state of extreme terror. The tiger appeared to be in a state of madness, and ran along the pavement in the direction of Ratcliff Highway, when it seized the little boy, John Wade, by the upper part of the right arm. The enraged animal was followed by Mr Jamrach and his men several yards, when the former obtained possession of a crowbar and struck the tiger upon the head and nose, which caused it to relinquish its hold. On the meantime ropes were procured, and the savage beast was secured and dragged into the premises, where it was firmly fastened up by the keepers. The poor boy was raised up by Stewart, the police officer, in a state of great suffering with two severe lacerated wounds on the arm and right side of the face, and it was quite a miracle that he was not torn to pieces. The teeth of the animal passed completely through the right arm. A cab was procured, in which the wounded boy was conveyed to the London Hospital, where Mr Forbes, the house surgeon, rendered assistance. The boy was in a very low state from loss of blood from the wounds, and last evening, at seven o'clock, he was in a very precarious condition, both from the injuries and shock to the system through fright. At the time of the escape of the animal the tradespeople in the neighbourhood closed their shops, and remained in a state of fear and anxiety for nearly half and hour afterwards. It seems that Mr Jamrach is an extensive importer and exported of all kinds of wild beasts and foreign birds, which he forwards to all parts of the world for menageries and private collections. Extraordinary Fight [14 November 1857] Our readers doubtless noticed, a few days back, an account of a tiger which escaped from a cattle truck in Ratcliff Highway, London, and which, after running along the centre of the road for some distance, was caught by his keeprs in the act of tearing a lad who unfortunately crossed the animal's path. The tiger was the property of Mr Jamrach, and he sold it a day or two afterwards to Mr Edmonds [for £200], the successor of Wombell, for his well-known travelling menageries, which it joined on Monday at West Bromwich. It was placed in one of the ordinary carriages, of two compartments, the adjoining den being occupied by a very fine lion, six or seven years old, for which Mr Edmonds gave £300 three years ago. The attendants had all left the menagerie to go to breakfast, when suddenly those in the carriage which the proprietors occupy was alarmed by an unusual outcry among the beasts. They soon discovered the cause. The newly-bought tiger had burglariously broken through the 'slide' or partition dividng his den from that of the lion, and had the latter in his terrible grasp. The combat which ensured was a terrific one. The lion acted chiefly on the defensive, and having probably been considerably tamed by his three years' confinement, the tiger had the advantage. His attacks were of the most ferocious kind. The lion's mane saved his head and neck from being much injured, but the savage assailant at last successed in ripping up his belly, and then the poor animal was at the tiger's mercy. The lion was dead in a few minutes. The scene was a fearful one. The inmates of every den seemed to be excited by the conflict, an their roaring and howling might have been heard a quarter of a mile distant. Of course Mr Edmonds and his men could not interfere while the conflict lasted, but when the tiger's fury had subsided they managed to remove the carcase. He must have used his paws as a sort of batterning ram against the partitition, as it was pushed rather than torn down. He cost Mr Edmonds £400. |

The boy's parents prosecuted and Jamrach was fined

£300. Other versions put the boy's age as eight. In

Harry Jones' account (but the incident was before his time in the

parish), it was a passer-by who used the crowbar, but missed the beast

and killed the boy. And another version says that there was no crowbar,

but Charles Jamrach forced his bare hands into the tiger's throat and

managed to release the boy unscathed. See also this account from the Boy's Own Paper of 1879 [illustration 'To the Rescue' right]. A fibreglass statue of the Boy and the Tiger, and of a Bear [left], were installed in Tobacco Dock as fundraisers for the World Wildlife Fund.

The boy's parents prosecuted and Jamrach was fined

£300. Other versions put the boy's age as eight. In

Harry Jones' account (but the incident was before his time in the

parish), it was a passer-by who used the crowbar, but missed the beast

and killed the boy. And another version says that there was no crowbar,

but Charles Jamrach forced his bare hands into the tiger's throat and

managed to release the boy unscathed. See also this account from the Boy's Own Paper of 1879 [illustration 'To the Rescue' right]. A fibreglass statue of the Boy and the Tiger, and of a Bear [left], were installed in Tobacco Dock as fundraisers for the World Wildlife Fund. The story is one of the real-life triggers for Carol Birch's novel Jamrach's Menagerie (Canongate / HarperCollins 2011), the other being the sinking of the whaling ship Essex in 1820 - see here

for a review. (The mix of fact and fiction is currently a popular genre

for books about East London - see above on the Marr murders, and also the series Call the Midwife.)

The story is one of the real-life triggers for Carol Birch's novel Jamrach's Menagerie (Canongate / HarperCollins 2011), the other being the sinking of the whaling ship Essex in 1820 - see here

for a review. (The mix of fact and fiction is currently a popular genre

for books about East London - see above on the Marr murders, and also the series Call the Midwife.)

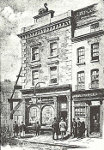

To the left of Jamrach's, at 182/3, was The Jolly Sailor [right, with the sign 'H. Harris'] - a dockworkers' pub, mentioned in The Metropolitan

magazine of 14 September 1872, and also by ex-Detective Sergeant

Benjamin Leeson in Lost London (Stanley Paul 1934). (He was involved in 'Ripper' enquiries, suffering an

attack by Ellen ('Dolly') Marks, and also in the investigation of the 1911 Sidney Street

siege.)

To the left of Jamrach's, at 182/3, was The Jolly Sailor [right, with the sign 'H. Harris'] - a dockworkers' pub, mentioned in The Metropolitan

magazine of 14 September 1872, and also by ex-Detective Sergeant

Benjamin Leeson in Lost London (Stanley Paul 1934). (He was involved in 'Ripper' enquiries, suffering an

attack by Ellen ('Dolly') Marks, and also in the investigation of the 1911 Sidney Street

siege.)| This,

which until within the last few years was

one of

the sights of the metropolis, and almost unique in Europe as a scene

of coarse riot and debauchery, is now chiefly noteworthy as an

example of what may be done by effective police supervision

thoroughly carried out. The dancing-rooms arid foreign cafés

of the

Highway — now rechristened St.

George’s-street — are still

well worthy a visit from the student of human nature, and are each,

for the most part, devoted almost exclusively to the

accommodation

of a single nationality. Thus at the Rose and Crown, near the western end of the Highway, the company will be principally Spanish and Maltese. At the Preussische Adler, just by the entrance into Wellclose-square, you will meet, as might be anticipated, German sailors; whilst Lawson’s, a little farther east, though kept by a German, finds its clientele among the Norwegian and Swedish sailors, who form no inconsiderable or despicable portion of the motley crews of our modem mercantile fleet. Over the way, a little farther down, is the Italian house, a quaint and quiet place, full of models and 'curios' of every conceivable and inconceivable description, and nearly opposite the large and strikingly clean caravanserai, where a pretty, but anxious-looking Maid of Athens receives daily, with a hospitality whose cordiality hardly seems to smack of fear, any number of gift-bearing Greeks. These two latter, by-the-way, are not dancing-rooms, but boarding-houses pure and simple; whilst farther still to the eastward is yet another variety in the shape of a music hall, where Dolly Dripping, the cook, in a draggled old print gown and a huge (natural) moustache; and Corporal Coldmutton, of the Guards, in a cast militia tunic, and a tattered pair of mufti inexpressibles; and Pleeseman X 999, in the general get up of a Guy Fawkes in a bankrupt pantomime, make simple fun for the edification of Quashie and Sambo, whose shining ebony faces stand jovially out even against the grimy blackness of the wails.  Perfectly

well conducted is the performance at the Bell,

without the smallest need to shrink from comparison in that

respect with the first of our West-end music halls. The performance

is not of a refined description, nor is the audience; but it is just

possible that, from an exclusively moral point of view, the advantage

may even be proved to be not altogether on the side of the higher

refinement. Hard by Quashie’s

music-hall is a narrow passage, dull

and empty, even at the lively hour of 11 pm., through which, by

devious ways, we penetrate at length to a squalid cul-de-sac,

which seems indeed the very end of all things. Chaos and

space

are here at present almost at odds which is which, for improvement

has at the present moment only reached the point of partial

destruction, and some of the dismal dog-holes still swarm with

squalid life, while others gape tenantless and ghastly with sightless

windows and darksome doorways, waiting their turn to be swept away

into the blank open space that yawns by their side. Perfectly

well conducted is the performance at the Bell,

without the smallest need to shrink from comparison in that

respect with the first of our West-end music halls. The performance

is not of a refined description, nor is the audience; but it is just

possible that, from an exclusively moral point of view, the advantage

may even be proved to be not altogether on the side of the higher

refinement. Hard by Quashie’s

music-hall is a narrow passage, dull

and empty, even at the lively hour of 11 pm., through which, by

devious ways, we penetrate at length to a squalid cul-de-sac,

which seems indeed the very end of all things. Chaos and

space

are here at present almost at odds which is which, for improvement

has at the present moment only reached the point of partial

destruction, and some of the dismal dog-holes still swarm with

squalid life, while others gape tenantless and ghastly with sightless

windows and darksome doorways, waiting their turn to be swept away

into the blank open space that yawns by their side. At the bottom of this slough of grimy Despond is the little breathless garret where Johnny the Chinaman swelters night and day curled up on his gruesome couch, carefully toasting in the dim flame of a smoky lamp the tiny lumps of delight which shall transport the opium-smoker for awhile into his paradise. If you are only a casual visitor you will not care for much of Johnny’s company, and will speedily find your way down the filthy creaking stairs into the reeking outer air, which appears almost fresh by contrast. Then Johnny, whose head and stomach are seasoned by the unceasing opium pipes of forty years, shuts the grimy window down with a shudder as unaffected as that with which you just now opened it, and toasts another little dab of the thick brown drug in readiness for the next comer. But if you visit Johnny as a customer, you pay your shilling, and curl yourself up on another grisly couch, which almost fills the remainder of the apartment. Johnny hands you an instrument like a broken-down flageolet, and the long supple brown fingers cram into its microscopic bowl the little modicum of magic, and you suck hard through it at the smoky little flame, and—if your stomach be educated and strong — pass duly off into elysium.   Then,

when your

blissful dream is over, you go your way, a wiser if not a sadder man.

Perhaps the most appropriate visit you can next pay is to the casual

ward of St. George’s Workhouse, hard by, at the bottom of Old

Gravel-lane, and thence, if it be not too late in the evening, to the

mission church of St. Peter’s, Dock-street, hard by, where

you will

find in full work an agency which, if the people of the neighbourhood

are to be believed, has had in the marvellous transformation

which has taken place a more potent influence oven than police and

parliament combined. Returning

thence to Shadwell High-street, you

may visit the White

Swan,

popularly known as 'Paddy’s

Goose', once the uproarious rendezvous of half the tramps and

thieves of London, now quiet, sedate, and, to confess the

truth,

dull—very dull [it housed a Wesleyan mission - see here for details: sketch left shows 'evangelical mission' next door; photo from 1926]. Down to the right here, again, is the little

waterside police-station, where the grim harvest of the

'drag',

the weird flotsam and jetsam of the cruel river, lies awaiting the

verdict that will— let us hope— 'find it

Christian burial'.

And so back into the highway again, and up Cannon-street road, where

stands St. George’s Church, the scene of the famous riots of

1858-59, which gave the first popular impulse to the

'ritualistic'

movement, and out into the wide Commercial-road, the boundary of

'Jack’s' dominion, beyond which again lie

the bustling

‘Yiddisher' quarter of Whitechapel and the swarming

squalor of

Spitalfields. Then,

when your

blissful dream is over, you go your way, a wiser if not a sadder man.

Perhaps the most appropriate visit you can next pay is to the casual

ward of St. George’s Workhouse, hard by, at the bottom of Old

Gravel-lane, and thence, if it be not too late in the evening, to the

mission church of St. Peter’s, Dock-street, hard by, where

you will

find in full work an agency which, if the people of the neighbourhood

are to be believed, has had in the marvellous transformation

which has taken place a more potent influence oven than police and

parliament combined. Returning

thence to Shadwell High-street, you

may visit the White

Swan,

popularly known as 'Paddy’s

Goose', once the uproarious rendezvous of half the tramps and

thieves of London, now quiet, sedate, and, to confess the

truth,

dull—very dull [it housed a Wesleyan mission - see here for details: sketch left shows 'evangelical mission' next door; photo from 1926]. Down to the right here, again, is the little

waterside police-station, where the grim harvest of the

'drag',

the weird flotsam and jetsam of the cruel river, lies awaiting the

verdict that will— let us hope— 'find it

Christian burial'.

And so back into the highway again, and up Cannon-street road, where

stands St. George’s Church, the scene of the famous riots of

1858-59, which gave the first popular impulse to the

'ritualistic'

movement, and out into the wide Commercial-road, the boundary of

'Jack’s' dominion, beyond which again lie

the bustling

‘Yiddisher' quarter of Whitechapel and the swarming

squalor of

Spitalfields.

|

See here

for some further Victorian descriptions of the area. Left are typical magazine illustrations of a soup kitchen and a 'singing saloon' on the Highway. In the early part

of the 20th century there was still a pub on nearly every corner, as

the map right, produced by the London United Temperance Council (founded

1895) shows. They opposed a number of licenses in the area, arguing

that in the 850 yards of St George's Street there were 26 licensed

premises (18 pubs and 8 beer houses), with between 56 and 68 other

premises with a quarter-mile radius of each. See here for a list of all the licensed premises in the St George-in-the-East district, and here for pictures of some of the former premises along the Commercial Road. (Now there are no pubs at all on The Highway - see below for the closure of The Old Rose and The Caxton.) See here for the listing from the

1921 London Street Directory for the north side of St George's Street,

which shows shows how most of the traders, and some of the publicans, were Jewish.

(The 'chandlers shops' referred to were not specifically nautical

suppliers by this date, but general 'corner shops'.)

See here

for some further Victorian descriptions of the area. Left are typical magazine illustrations of a soup kitchen and a 'singing saloon' on the Highway. In the early part

of the 20th century there was still a pub on nearly every corner, as

the map right, produced by the London United Temperance Council (founded

1895) shows. They opposed a number of licenses in the area, arguing

that in the 850 yards of St George's Street there were 26 licensed

premises (18 pubs and 8 beer houses), with between 56 and 68 other

premises with a quarter-mile radius of each. See here for a list of all the licensed premises in the St George-in-the-East district, and here for pictures of some of the former premises along the Commercial Road. (Now there are no pubs at all on The Highway - see below for the closure of The Old Rose and The Caxton.) See here for the listing from the

1921 London Street Directory for the north side of St George's Street,

which shows shows how most of the traders, and some of the publicans, were Jewish.

(The 'chandlers shops' referred to were not specifically nautical

suppliers by this date, but general 'corner shops'.)

In 1978, marking a hundred years of Salvation Army bands, Ray Steadman-Allen - [left - a much-loved figure, still active in his 90s], composed Victorian Snapshots: On Ratcliff Highway, named from a War Cry sketch 'Our Whitechapel Soldiers marching the Ratcliff Highway, London in 1886' [modern version right]. It is a series of shuffled snatches of popular songs of the day, combined with hymns such as Hold the fort! and the sounds of Big Ben - here is an 1981 audio recording by Kettering Citadel Band, and here a full description and American video of the work.

In 1978, marking a hundred years of Salvation Army bands, Ray Steadman-Allen - [left - a much-loved figure, still active in his 90s], composed Victorian Snapshots: On Ratcliff Highway, named from a War Cry sketch 'Our Whitechapel Soldiers marching the Ratcliff Highway, London in 1886' [modern version right]. It is a series of shuffled snatches of popular songs of the day, combined with hymns such as Hold the fort! and the sounds of Big Ben - here is an 1981 audio recording by Kettering Citadel Band, and here a full description and American video of the work.  Two Denmark Street factories

Two Denmark Street factories

This phrase, though used from the 17th century, is sometimes linked with the

firm founded by Thomas Keen

in 1742 at Garlick Hill. English mustard

was originally called 'Durham mustard' as it was made by Mrs Clements

of Durham. It was popularised as an accompaniment to roast beef by

King George I, and in succeeding years Keen's were granted royal warrants by King William IV, Queen Victoria and

Napoleon III. They manufactured other spices (including curry powder,

exported to Australia from the 1840s), and oatmeal and ground

rice, and made their own tins, filled in the 'penny packing room'.

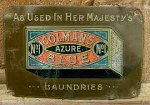

Another

product was Oxford blue for laundry, which stained everything,

including the workers, so was done in a sealed area of the

factory. [Left are later images, of ginger grinding, Keen's laundry blue packing room and a rival product].

This phrase, though used from the 17th century, is sometimes linked with the

firm founded by Thomas Keen

in 1742 at Garlick Hill. English mustard

was originally called 'Durham mustard' as it was made by Mrs Clements

of Durham. It was popularised as an accompaniment to roast beef by

King George I, and in succeeding years Keen's were granted royal warrants by King William IV, Queen Victoria and

Napoleon III. They manufactured other spices (including curry powder,

exported to Australia from the 1840s), and oatmeal and ground

rice, and made their own tins, filled in the 'penny packing room'.

Another

product was Oxford blue for laundry, which stained everything,

including the workers, so was done in a sealed area of the

factory. [Left are later images, of ginger grinding, Keen's laundry blue packing room and a rival product].|

Specification of the Patent granted to MATTHIAS ARCHIBALD ROBINSON for improvements in the mode of preparing the vegetable matter commonly called pearl barley, and grits, or groats, made from the corn of barley, and oats, by which material, when so prepared, a superior mucilaginous beverage, may be produced in a few minutes. To

all to whom these presents shall come &c. Now know ye,

that in compliance with the said proviso, I, the said Matthias

Archibald Robinson, do hereby declare, that the nature of my said

invention, and the manner in which the same is to be performed, are

particularly described and ascertained in the following description

thereof: (that is to say) My invention of certain improvements in the

modes of preparing the vegetable matters, commonly called pearl

barley, and grits or groats, consists of a peculiar mode of drying,

and otherwise treating the grain, by which process its vegetative

properties are destroyed, and a meal is produced, divested of rawness

and free from the impurities of husk or fibre, which meal, when so

prepared, is soluble in water and will make a fine mucilage, in a few

minutes. Any quantity of pearl barley, or groats, intended to be

operated upon, is taken in the state it is usually sold, and the

first process in preparing is to cleanse it, by winnowing from seeds,

husks, dirt, dust, and other impurities. After this the grain is

carefully looked over, and any extraneous matters, which have not

been separated by the winnowing separated by winnowing, are then

picked out. In this cleansed state, the grain is put into sieves, and

spread over their bottoms in level layers, about three quarters of an

inch thick. The sieves are then deposited on ledges, in closets

heated by steam boxes, or steam passages, the temperature of which

should be gradually increased to 160° or 170° of Fahrenheit's

thermometer. Under this temperature the grain must be suffered to

remain, drying gradually, for about four hours, the aqueous parts

evaporated, being drawn off by suitable pipes, leading from the hot

closets. By these means, the vegetative properties of the grain will

be destroyed, and the raw taste removed, without parching or roasting

it. When the grain has been thus sufficiently dried, it is spread out

in hoppers, or troughs, to cool, and when that is effected, it is to

be passed through funnels, to the hoppers, down to steel mills, (if

ground by stone, they are liable to gritty substances;) where it is

ground by steam, or any other efficient power; sliders must be

introduced into the funnels, for the purpose of regulating the

supply. The meal, falling from the steel mills, is received into

boxes or receivers, and is thence removed, for dressing, into bolting

machinery of the ordinary construction. The cylinders of the bolting

machines should be made of fine wire gauze, from twenty-four, to

forty-eight, in the inch, and when the meal has passed through the

finest of these, it may be considered to be completely fit for use. A

table-spoonful of the prepared barley meal, may be mixed up in two

spoonsful of cold water, and when perfectly smooth, one quart of

boiling water is to be poured upon it. This being suffered to boil

for ten minutes, will produce the mucilage called barley water, which

should be then strained through muslin, if required, flavoured with

lemon peel or juice, and sweetened with honey, refined sugar, or

sugar candy An excellent food for infants may be made, by mixing the

above proportion with milk and water, instead of water alone. It will

also be found to be a very desirable material for thickening broths;

it may be mixed and introduced into the broth half an hour before it

is taken off the fire. Puddings, of an excellent quality, may also be

made from the prepared barley meal; the powder of the prepared groats

is to be mixed in the same way, and a gruel may be produced in ten

minutes, of a quality very much superior to any other gruel, made

from any preparation of grits or oatmeal, heretofore introduced to

the public. I am aware, that several variations may be made in the

process above described; but I wish it to be understood that I rest

my claim of patent right, in a method or methods of drying the grain

under a regular temperature, without roasting or parching, it so as

to destroy its vegetative properties, and at the same time retain its

nutritive qualities unimpaired, and of clearing it from its fibrous

and husky parts, after grinding, leaving only the pure and fine meal;

by which preparation, the meal is brought into a condition, that will

enable it to keep perfectly good, in any climate. |

Every product

bore his signature [advertisement left from 1828]. By 1839 they were Robinson & Belville [advertisement left from 1839]. They

too had the patronage of William IV and Queen Victoria. In the 1850s

they sent their products to

help to sustain our gallant army in the Crimea. Their groats and barley were patented in 1862.

Every product

bore his signature [advertisement left from 1828]. By 1839 they were Robinson & Belville [advertisement left from 1839]. They

too had the patronage of William IV and Queen Victoria. In the 1850s

they sent their products to

help to sustain our gallant army in the Crimea. Their groats and barley were patented in 1862.

The

firm was now known as Keen, Robinson & Co, a limited liability company, blue starch and mustard manufacturers, though there was a

spat with the Post Office over using the full name 'Keen, Robinson,

Belleville & Company' on their letter dies: they were

unsuccessfully reported to Mr Boucher, Controller of the Circulation

Department for infringing the regulations.

The

merger required a larger factory, which was built in the 1880s in Denmark [now

Crowder] Street, with offices at St George's Street [now The Highway]. It was known as 'New Central'. Left is the exterior, and right the

barley mills (powered by a beam engine) and the mustard packing room,

together with an 1864 mustard advertisement. From that year they also advertised as agents for 'Oswego prepared corn starch', a

popular export to Australia at the time, where many settlers' cooking facilities

were limited. In 1866 they were also advertising split peas and pearl barley, and in 1872 finest Spanish semolina, of which one commentator said it was particularly white, and seemed well-prepared; it was sold in 1lb tin canisters.They won a prize medal in Dublin in 1862 [left] - where they also displayed 'Bruges chicory', as a coffee additive or substitute; were award winners in the British section at the 1876 Philadelphia International Exhibtion; exhibited genuine mustard and process of manufacture at the 1866/7 Paris exhibition; they also won medals in London, Moscow and Australia.

The

firm was now known as Keen, Robinson & Co, a limited liability company, blue starch and mustard manufacturers, though there was a

spat with the Post Office over using the full name 'Keen, Robinson,

Belleville & Company' on their letter dies: they were

unsuccessfully reported to Mr Boucher, Controller of the Circulation

Department for infringing the regulations.

The

merger required a larger factory, which was built in the 1880s in Denmark [now

Crowder] Street, with offices at St George's Street [now The Highway]. It was known as 'New Central'. Left is the exterior, and right the

barley mills (powered by a beam engine) and the mustard packing room,

together with an 1864 mustard advertisement. From that year they also advertised as agents for 'Oswego prepared corn starch', a

popular export to Australia at the time, where many settlers' cooking facilities

were limited. In 1866 they were also advertising split peas and pearl barley, and in 1872 finest Spanish semolina, of which one commentator said it was particularly white, and seemed well-prepared; it was sold in 1lb tin canisters.They won a prize medal in Dublin in 1862 [left] - where they also displayed 'Bruges chicory', as a coffee additive or substitute; were award winners in the British section at the 1876 Philadelphia International Exhibtion; exhibited genuine mustard and process of manufacture at the 1866/7 Paris exhibition; they also won medals in London, Moscow and Australia.

| Adulterated Arrowroot At Shepton Mallet Petty Sessions, Mrs. Caroline Everett, grocer, of Shepton Mallet, was charged by Mr. Bisgood, deputy chief constable of Somerset, with selling adulterated arrowroot. Police- constable Hoddinott stated that he went to the defendant's shop and asked for an ounce of arrowroot, in order that he might have it analysed. Mr. Bowden, the assistant, brought into the shop a tin box of arrowroot that had not previously been opened, and opened it in the presence of witness, and supplied him with arrowroot therefrom. The box was labelled 'warranted genuine', and Mr. Bowden wrote similar words on the packet he produced. Mr. Bisgood proved taking the samples to Mr. W. W. Stoddort, Park Street, the county analyst. He had since received a certificate from Mr Stoddart, which he handed in. It stated that the srrowroot in question contained 50 per cent. of cassava starch. Mr. Wontner, of London, who appeared for the wholesale house that supplied the the arrowroot, said he represented the firm of Keen, Robinson, Bellville, and Company, of London, who had sold the arrowroot to Mrs. Everett, and were also themselves summoned. On the part of Mrs. Everett, he submitted that she has sold the arrowroot in the same condition that she bought it, and had given notivce to that effect when she sold it to the constable. She was therefore protected by the 25th section of the Act. The bench agreed with this opinion, and dismissed the case. Mr. William John Bellville, trading as Keen, Robinson, Bellville, and Company, spice merchants, of no.6, Garlick-hill, Cannon-street, London, was next charged with selling fourteen pounds of adulterate arrowroot to Mrs. Everett. Mr. Wontner said the facts were admitted by the firm, who claimed the same protection under the Act as Mrs. Everett, and would prove that they had sold the arrowroot in precisely the same condition as they had bought it, and as it was imported. It was the custom of the firm he represented to submit samples of all goods purchased by them to Mr. Piesse, the public analyst of the Strand, for analysis, before warranting them to their customers, but during last summer Mr. Bellville was out of town, for the benefit of his health, and Mr. Swinbourne their spice buyer and salesman, was laid up for six weeks by an accident, and when he returned to business he found a great demand for Natal arrowroot, and he went into the market and bought six cases under warranty from sworn brokers, and being anxious to supply the customers of the firm he did not wait to have it analysed. Since these proceedings had been taken they sent a sample to Mr. Piesse,who found the arrowroot wa not genuine, and they had accordingly withdrawn all they had sold from that lot. It contained a mixture of starch of cassava, which was a wild arrowroot. He also thought that as this description of goods was imported and passed through the Custom-house its purity should be guaranteed, as in the case of tea. Mr. Swinbourne the spice buyer and salesman of the defendant, was then called, and he proved purchasing the arrowroot of Messrs Bryant and Wheeler as it was imported, and selling the same to Mrs. Everett. The Chairman of the Bench (Capt Ernst) said the only difference they could see in the two cases was that Mrs. Everett had given notice that she sold the arrowroot in the same condition that she bought it, and the defendants had not; they would therefore have to pay the costs, and the case would be dismissed. |

One

person who had a lifelong career with the company was William

Mansfield, who in 1891 was living in Whitfield Street, near Tottenham

Court Road with his wife Elizabeth and to young sons; in 1901 at 5

Bewley Street (see here for the Dellow and Bewley Buildings). Ten years later (having retired?) he was back west, off Regent Street.

So he appears to have straddled the amalgamated firm's two bases. (We're grateful to his great-granddaughter Gill Harden for this and other family information.)

On 19 June 1897 the Brisbane Queenslander reported:

| Among the leading firms in the mustard and kindred trades none is better known than Messrs. Keen, Robinson, and Co., Limited, with head offices at Garlick Hill, Cannon-street, E.C., and such a firm, though well known and old established, is not likely to be behindhand when an exhibition Is to be held at a leading centre of British colonial trade. They have therefore prepared a very striking show of their goods. On the several levels the firm's specialities, for which they have been so long celebrated, are ranged, and In well got up cases are shown stereos [sic] of the various medals acquired. The upper part of the stand is taken up with four splendid shields bearing the name of the firm, and the date established—1742. The eye being thus attracted, we turn to the exhibits themselves, and find specimens of Keen's mustard and Oxford blues for laundry purposes, while the second name in the firm is associated with Robinson's patent groats, first introduced in 1823, a speciality which has obtained a world-wide reputation for making gruel, so necessary to nursing mothers and invalids. Another article bearing Robinson's name is the firm's patent barley, brought out at the same time as the groats, and which is a preparation for making barley water in ten minutes, as against the old fashioned way, which we all know takes hours. The medical profession have discovered that this is one if not the best of foods for Infants, while barley water, mixed with milk, separates the caseine, and thus enables the weakest child to digest cow's milk, when it is deprived of its natural food from the breast. A more modern article on this stand is the Waverley oats. This has become also very popular, and takes! the place of oatmeal as a porridge for breakfast. It Is partly cooked, and therefore requires only ten minutes to prepare for the table. Another article shown, and which is fully appreciated in the colony, is Keen's Oxford blue. It is packed in loz. and ½oz. squares, also In circular blocks wrapped in calico ready for use. The manufacturers claim superiority on the ground of cleanliness, solubility, and economy, and, with their long reputation to preserve, it may be fairly certain their claims are good ones. Adjoining their stand is the office, and no effort has been spared even here to make a show. Every particle of space has been utilised to exhibit specimens of the firm's well-known cards and frames, each of which is a work of art in itself. Messrs. D. L. Brown and Co. are the Brisbane agents for the products of Messrs. Keen, Robinson, and Co., Limited. |

The British Journal of Nursing Supplement of 1914 added: The value of barley water as a dilutent of milk is well known, and that made from Robinson's Patent Barley is found most successful in use, both in the case of infants, when breast feeding is impossible, and also as a summer drink for invalids. It is supplied by Keen, Robinson & Co, Ltd Denmark Street, London E.

Under

the Trade Boards Act of 1909 - an innovative if somewhat bureaucratic

piece of legislation - a Board was set up (in 1914, for three

years and thereafter until dissolved) for those involved in making tinplate

boxes and canisters (excluding the sealing of filled boxes and

canisters with solder, and excluding the following branches of work,

namely, the lining of packing-cases with tinplate, the making of

trunks, uniform cases, suit and dress cases, bonnet and helmet boxed,

cash and deed-boxes, despatch boxes, letter-boxes, kegs and drums,

and any other branch of work which does not form part of the tin box

and canister trade), with 29 nominees each from employers and

employees. Among the former was Mr T. Balls of Keen Robinson &

Co., Ltd.

Keen's

Mustard Club was created in the 1930s, with badges and 'inner secrets',

and prepared mustard baths were sold in this period. In

1935 Robinson's

'ready to use' Barley Water - a prepared drink of barley, lemon juice, sugar and

water - was created for the Wimbledon tennis championships and

became a popular summer drink, not just for invalids! [Advertisements right from 1939 - along with continued advertising of barley and groats for nursing mothers - and 1953.] In 1956 Colmans became part of Reckitt and Colman (the name Colman Keen continued in New Zealand and elsewhere), and in 1995 was

sold to Unilever (Britvic taking over the Robinson's brand). McCormick took over the Keen's brand in Canada and

Australia, where Norwich-made products are still available (including genuine double superfine dry mustard, by appointment to Queen

Elizabeth II, as well as prepared mustard).'Keen's Curry' T-shirts were also produced.

Yeatman & Co

was

established

in 1857 by Israel Edward Woolf, at 119 New Bond Street (where another

family venture, the Atmospheric Churn Company, selling refrigeration

and butter churning equipment, with agencies in Brussels and Berlin,

was dissolved in 1889 and finally wound up in 1906). Their success in

selling yeast powder to the troops

abroad enabled the setting up of the factory in Denmark Street. They diversified: at

their 1884 stand at the Health Exhibition (still using the New Bond Street address), they advertised Yeast Powder, Baking

Powders, Flour, Self-raising Flour,

Corn Flour, Callsayme Bitters* , Lime-juice

Cordial, Custard Powder, Egg Powders, Curry Powder,

Flavouring Essences, Disinfecting Powder and Insect Powder; left is their range as advertised in

Charles Clarke's High Class Cookery

(1885).

was

established

in 1857 by Israel Edward Woolf, at 119 New Bond Street (where another

family venture, the Atmospheric Churn Company, selling refrigeration

and butter churning equipment, with agencies in Brussels and Berlin,

was dissolved in 1889 and finally wound up in 1906). Their success in

selling yeast powder to the troops

abroad enabled the setting up of the factory in Denmark Street. They diversified: at

their 1884 stand at the Health Exhibition (still using the New Bond Street address), they advertised Yeast Powder, Baking

Powders, Flour, Self-raising Flour,

Corn Flour, Callsayme Bitters* , Lime-juice

Cordial, Custard Powder, Egg Powders, Curry Powder,

Flavouring Essences, Disinfecting Powder and Insect Powder; left is their range as advertised in

Charles Clarke's High Class Cookery

(1885).

[*Calisayine Cocktail Bitters was based on the South American

bark from which quinine is obtained - they also made a quinine wine.]

The Nursing Record & Hospital World for 1899 commended their ginger

marmalade and coffee extract, as tasting more of coffee than other similar products.

It became a

limited liability company in 1898, with capital of £200,000, based at 11 Denmark

[later renamed Crowder] Street, with an office at 78 St George's Street,

and their box-making department, the Yebel Press,

at 41-43 St George's Street ('Yebel'

remained the company's telegraphic address, hinting at its Jewish

roots - it is the Hebrew word for 'mountain'). By now as well as

cornflour and vinegar they were also making soups, jams, jellies and

sweets,

in the early years of the 20th century exporting to Australasia

'Yeatman's Delicious Jelly Tablets' in a range of flavours [right].

In the following years suppliers in England and New Zealand were

selling 2lb. jars of 'St George's Jam' - was this also a Yeatman's

product? In the 1930s, they were one of the first suppliers of sweets to Marks & Spencers. Denys Munby, in his exhaustive 1951 review of industry in

Stepney, notes that they were one of three small sweet-making

factories left in Stepney.Their premises suffered in the Blitz, and

the jam factory was destroyed by fire in 1946, though they retained

their head office here for some time (telephone ROYal

6877 - the local exchange - as well as PUTney 6333).

It became a

limited liability company in 1898, with capital of £200,000, based at 11 Denmark

[later renamed Crowder] Street, with an office at 78 St George's Street,

and their box-making department, the Yebel Press,

at 41-43 St George's Street ('Yebel'

remained the company's telegraphic address, hinting at its Jewish

roots - it is the Hebrew word for 'mountain'). By now as well as

cornflour and vinegar they were also making soups, jams, jellies and

sweets,

in the early years of the 20th century exporting to Australasia

'Yeatman's Delicious Jelly Tablets' in a range of flavours [right].

In the following years suppliers in England and New Zealand were

selling 2lb. jars of 'St George's Jam' - was this also a Yeatman's

product? In the 1930s, they were one of the first suppliers of sweets to Marks & Spencers. Denys Munby, in his exhaustive 1951 review of industry in

Stepney, notes that they were one of three small sweet-making

factories left in Stepney.Their premises suffered in the Blitz, and

the jam factory was destroyed by fire in 1946, though they retained

their head office here for some time (telephone ROYal

6877 - the local exchange - as well as PUTney 6333).

With government help to get war-damaged firms back on their feet, in 1942 they established Cherry Tree Works in Watford, where

they canned and bottled fruit, made fruit squashes, and their

best-remembered product, Sunny Spread (a blend of honey and invert sugar).

Left are advertisements from

1953 and (with a price-cut) 1954, and an image of the characteristic

jar. In the 1960s they advertised in the British Bee Journal attractive

addressed honey labels - 250 for 8s. 6d., 500 for 16s., 1,000 for

26s; samples 2d.; gold lacquered snap-on lids, for jam

jars, 14s. 6d. a gross. Inigo Woolf

(chief executive of the London Diocesan Board for Schools) recalls

touring this factory when his grandfather was the managing director -

he was the youngest brother of 15 children, taking over from two

brothers twenty years his senior; we are grateful to Inigo for many of these details. They were proud of their technical

innovations (including keeping the colour of cherries in prepared

products). When

the business was sold to Cavenham Foods, and production transferred to

Carrs of

Carlisle, the Watford works became the headquarters of Mothercare; the

family retained some of their recipes, including that for Christmas

pudding.

With government help to get war-damaged firms back on their feet, in 1942 they established Cherry Tree Works in Watford, where

they canned and bottled fruit, made fruit squashes, and their

best-remembered product, Sunny Spread (a blend of honey and invert sugar).

Left are advertisements from

1953 and (with a price-cut) 1954, and an image of the characteristic

jar. In the 1960s they advertised in the British Bee Journal attractive

addressed honey labels - 250 for 8s. 6d., 500 for 16s., 1,000 for

26s; samples 2d.; gold lacquered snap-on lids, for jam

jars, 14s. 6d. a gross. Inigo Woolf

(chief executive of the London Diocesan Board for Schools) recalls

touring this factory when his grandfather was the managing director -

he was the youngest brother of 15 children, taking over from two

brothers twenty years his senior; we are grateful to Inigo for many of these details. They were proud of their technical

innovations (including keeping the colour of cherries in prepared

products). When

the business was sold to Cavenham Foods, and production transferred to

Carrs of

Carlisle, the Watford works became the headquarters of Mothercare; the

family retained some of their recipes, including that for Christmas

pudding.

The street was named for Captain Cook's wife, Elizabeth Batts or Betts (1742–1835) - right

is Betts House today. In its early years it had a number of respectable

and middle-class residents; for example, in the 1820s James Peckett at

no.10 was a supporter of the British and Foreign Schools Society.

The Desormeaux family - Huguenots - lived at no.30; Cornelius and

Abraham were both 'deputy coal meters', listed in 1794 and 1797 among

the 'supernumerary men' who assessed coal payments under the intricate 'chaldron' system. [Jim Desormeaux, a key member of Christ Church Watney Street in Fr Groser's time, was presumably a distant relative.] See here for Henry Nibbs Brown(e), who had a sugar refinery at no.9 in the 1820s.

The street was named for Captain Cook's wife, Elizabeth Batts or Betts (1742–1835) - right

is Betts House today. In its early years it had a number of respectable

and middle-class residents; for example, in the 1820s James Peckett at

no.10 was a supporter of the British and Foreign Schools Society.

The Desormeaux family - Huguenots - lived at no.30; Cornelius and

Abraham were both 'deputy coal meters', listed in 1794 and 1797 among

the 'supernumerary men' who assessed coal payments under the intricate 'chaldron' system. [Jim Desormeaux, a key member of Christ Church Watney Street in Fr Groser's time, was presumably a distant relative.] See here for Henry Nibbs Brown(e), who had a sugar refinery at no.9 in the 1820s.

From 1863-1879 George Fletcher & Co

was based at 21 [or 42] Betts Street. George Fletcher was born in

Alfreton in 1810, and in 1839 established a works in Lambeth (moving to

Borough) manufacturing sugar processing machinery for the West Indies. Among their patents was the multitubular boiler for the copper hall. Production transferred here in 1863

[advert left from 1874 - they advertised all around the world - and

'grasshopper engine' of 1850s, at one time in London but now at the

Silk Mill, Derby], but at the same time he started building a larger

factory at Masson Works, Derby, by the new Derby to Birmingham railway.

London production shifted to Poplar Iron Works in 1879, with a City

office at 21 Mincing Lane, but the head office moved to Derby. On his

death his namesake son inherited the firm, and on his death it was left

to his six children, but with a 2/7 share to one daughter, so her

sisters went to law and it was ruled that the company should be sold;

family members bought it up in 1909 when it was incorporated. It grew,

as Fletcher-Edwards; was acquired by Booker Brothers, McConnell &

Co in 1956 and became Fletcher & Stewart in 1962 following a merger

with a Scottish firm Duncan Stewart & Co; further mergers and name

changes followed.

From 1863-1879 George Fletcher & Co

was based at 21 [or 42] Betts Street. George Fletcher was born in

Alfreton in 1810, and in 1839 established a works in Lambeth (moving to

Borough) manufacturing sugar processing machinery for the West Indies. Among their patents was the multitubular boiler for the copper hall. Production transferred here in 1863

[advert left from 1874 - they advertised all around the world - and

'grasshopper engine' of 1850s, at one time in London but now at the

Silk Mill, Derby], but at the same time he started building a larger

factory at Masson Works, Derby, by the new Derby to Birmingham railway.

London production shifted to Poplar Iron Works in 1879, with a City

office at 21 Mincing Lane, but the head office moved to Derby. On his

death his namesake son inherited the firm, and on his death it was left

to his six children, but with a 2/7 share to one daughter, so her

sisters went to law and it was ruled that the company should be sold;

family members bought it up in 1909 when it was incorporated. It grew,

as Fletcher-Edwards; was acquired by Booker Brothers, McConnell &

Co in 1956 and became Fletcher & Stewart in 1962 following a merger

with a Scottish firm Duncan Stewart & Co; further mergers and name

changes followed.|

While I was thus hammering out some new design on the Anvil of

experience, I bethought my self where probably I might find my Wife:

First, I went to Ratcliff high-way, and made enquiry of Dammaris,

&c., the Metropolitan Bawd of those parts, for a Gentlewoman of such

a complexion, stature, and age, ('twas but a folly to mention her name,

for those that follow that trade change their names as often as they do

their places of abode) but that cart-load of flesh could give me no

information, neither was it possible for me to have staid to hear it,

she so stunk of Strong-waters, stronger then that Cask that never

contained any thing else; I went down all along to the Cross, in my way

I saw many Whores standing at their doors, giving me invitation; but

being poor, they could not afford the charge of Fucus,

so that their faces lookt much like a piece of rumbled Parchment, and

by their continual traffick with Seamens Breeches, I could not come

near them, they smelt so strongly of Tarpawlin and stinking Cod; yet

still no tidings of her I sought for. |

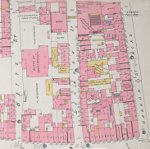

Although in 1875 Harry

Jones commented on the rough nature of the street, including Jamrach's keeping of wild animals, he later said that it had been transformed. Goad's 1887 insurance map [left] of

the southern ends of Betts and Denmark [Crowder] Street, together with

Betts, Hope and Rodgers Courts, shows the area after the building of

the large Board School in 1884 but prior to the swimming bath and wash-houses [1890 drawing right]. Mary Steer's Bridge of Hope Mission opened in new premises here in 1888.

Although in 1875 Harry

Jones commented on the rough nature of the street, including Jamrach's keeping of wild animals, he later said that it had been transformed. Goad's 1887 insurance map [left] of

the southern ends of Betts and Denmark [Crowder] Street, together with

Betts, Hope and Rodgers Courts, shows the area after the building of

the large Board School in 1884 but prior to the swimming bath and wash-houses [1890 drawing right]. Mary Steer's Bridge of Hope Mission opened in new premises here in 1888.

The street

scene is from c1910 (showing the school). See here for details of the Oxford & St George's Clubs premises in the street from 1919-29. The school, laundry and baths [left] have

long gone - local boy Steven Berkoff used to swim there in the winter. Iin the 1970s, St George's Pools

were built on The Highway to provide local swimming and other facilities. From that decade comes this picture [right - one of many by Dan Jones] of an adventure playground in Crowder Street.

The street

scene is from c1910 (showing the school). See here for details of the Oxford & St George's Clubs premises in the street from 1919-29. The school, laundry and baths [left] have

long gone - local boy Steven Berkoff used to swim there in the winter. Iin the 1970s, St George's Pools

were built on The Highway to provide local swimming and other facilities. From that decade comes this picture [right - one of many by Dan Jones] of an adventure playground in Crowder Street.Pennington Street and its four 'hills'

Pennington

Street runs parallel to, and just south of, The Highway. It was laid

out in 1650s by John Pennington, on the north of Wapping Marsh, and now

forms part of the northern boundary of the former London Docks (and of

the present parish of St George-in-the-East). Its southern side

presents a forbidding aspect -

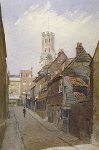

the high outer dock wall behind Tobacco Dock [right, plus no.2 warehouse] and, to the east, the rear of the Rum Warehouse. Left is

Goad's 1887 insurance map of the area bounded by St George's Street and

Pennington Lane, between Virginia Street, Breezer's Hill, Artichoke Hill (including Grove Place and

Pennington Place), St John's Hill (including George Yard, leading to a wheelwright's), Chigwell Hill and Old Gravel [Wapping] Lane.

Pennington

Street runs parallel to, and just south of, The Highway. It was laid

out in 1650s by John Pennington, on the north of Wapping Marsh, and now

forms part of the northern boundary of the former London Docks (and of

the present parish of St George-in-the-East). Its southern side

presents a forbidding aspect -

the high outer dock wall behind Tobacco Dock [right, plus no.2 warehouse] and, to the east, the rear of the Rum Warehouse. Left is

Goad's 1887 insurance map of the area bounded by St George's Street and

Pennington Lane, between Virginia Street, Breezer's Hill, Artichoke Hill (including Grove Place and

Pennington Place), St John's Hill (including George Yard, leading to a wheelwright's), Chigwell Hill and Old Gravel [Wapping] Lane.

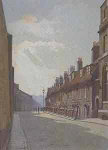

On

the north side were once two- and three-storey houses, some pre-dating

the Docks and others built at around the same time, and described even

then as almost without exception mere hovels, when compared to the habitations in the City of London. With

two dock gates on the street, it was a busy thoroughfare. Left are two views from c1878 (of 110-122 and 134-143), one from 1906 and two undated.

On

the north side were once two- and three-storey houses, some pre-dating

the Docks and others built at around the same time, and described even

then as almost without exception mere hovels, when compared to the habitations in the City of London. With

two dock gates on the street, it was a busy thoroughfare. Left are two views from c1878 (of 110-122 and 134-143), one from 1906 and two undated.

Right is

a view from the 1980s, when the area was in the doldrums. Despite the

building of new flats and office space, it remain a somewhat desolate

location, with criminal activity including drug dealing. In December

2013 there were stabbings at an illegal 'Santa Stomp' rave. There are

attempts to improve things: for instance, a former nightclub site at

no.110 is now a photographic and event space, with two studios (Black

and White) - far right - and local people look forward to the regeneration of the former News International site, and the empty lot on the corner of The Highway and Wapping Lane.

Right is

a view from the 1980s, when the area was in the doldrums. Despite the

building of new flats and office space, it remain a somewhat desolate

location, with criminal activity including drug dealing. In December

2013 there were stabbings at an illegal 'Santa Stomp' rave. There are

attempts to improve things: for instance, a former nightclub site at

no.110 is now a photographic and event space, with two studios (Black

and White) - far right - and local people look forward to the regeneration of the former News International site, and the empty lot on the corner of The Highway and Wapping Lane. Four

short streets (each now about 80m long) run down from The Highway to

Pennington Street and the northern boundary of the London Docks - from

west to east, Breezer's Hill, Artichoke (previously spelt Artichoak)

Hill, St John's Hill and Chigwell Hill.

Four

short streets (each now about 80m long) run down from The Highway to

Pennington Street and the northern boundary of the London Docks - from

west to east, Breezer's Hill, Artichoke (previously spelt Artichoak)

Hill, St John's Hill and Chigwell Hill.

(1) Breezer's Hill is a 'Ripper site', as Mary Kelly was

believed to have lived here briefly in 1885. There had been a pub at

each end – the White Bear at the top (1 St George's Street), where Mary

no doubt drank, and the Red Lion at the bottom, which had closed in

1874.

(2) Artichoke Hill and (3) St John's Hill

once enclosed a square of small houses which gave onto a central piece

of ground. Artichoke Lane

was further to the south-west, at the bottom of Virginia Street, near

the Hermitage; there was a major fire there in 1792 (before the Docks

were built). - there was a major

fire on Artichoke Hill. Among the various surviving documentsis this touching appeal for a charity school place:

(2) Artichoke Hill and (3) St John's Hill

once enclosed a square of small houses which gave onto a central piece

of ground. Artichoke Lane

was further to the south-west, at the bottom of Virginia Street, near

the Hermitage; there was a major fire there in 1792 (before the Docks

were built). - there was a major

fire on Artichoke Hill. Among the various surviving documentsis this touching appeal for a charity school place:

| Mr

Cockshead I Beg Pardon for givin you this Trouble but hope your good

Hart will Exscuse me when I inform you I am a Sufferer by the Late Fire

in Hartychoke Laine No 30. We moved all our goods and in Moving Broke

and Lost Sevrell Yousfull Artickls tho to no Greet Amount but have no

Inchourance. My Greatist Los and Trouble is by Sending my 5 Dr

Children in to Wapping at that Early Oure in the Morning ... and 2 of

them has Never Louked up Since. The Youngist But wone I am Afrade Will

never be Restored in health to me A Gane. I have only to Say Good Sir

if you Would Plase A Sist me with a Trifell it will be of the Greatist

Sarvice to a Distress'd Famley and most thank fully Receved By Sir Your

Humble svt Ann Blenkinsop. |

29 St George's Street, scene of the first Ratcliff Highway murder in 1811, lay

between Artichoke Hill and St John's Hill [it is now the site of a car

showroom]. William Harrison Ainsworth's serially-published novel of

1839 Jack Sheppard (vol 2, p229) refers to a miserable quarter between Artichoke Lane and Nightingale Lane .... termed the New Mint. [Right is the corner of St John's Hill]

29 St George's Street, scene of the first Ratcliff Highway murder in 1811, lay

between Artichoke Hill and St John's Hill [it is now the site of a car

showroom]. William Harrison Ainsworth's serially-published novel of

1839 Jack Sheppard (vol 2, p229) refers to a miserable quarter between Artichoke Lane and Nightingale Lane .... termed the New Mint. [Right is the corner of St John's Hill]

Some of the German sugar bakers settled here. It also housed small workshops; for example, in 1852 John Akrill of Artichoke Hill was granted a patent for 'improvements in the manufacture of bricks, tiles and other earthenware articles'. (A century later, an engineering firm manufacturing farm equipment was based here.) By the turn of the century, the area was filled with sailors' brothels, and was often visited by voyeurs from high society in search of a cheap thrill.

The

Artichoke Tavern stood on the corner of Artichoke Hill, at 19 St

George's Street [now 50 The Highway]; it was rebuilt in the mid-20th

century and later renamed The Caxton [left]; in 2012 it became a Domino's pizza takeaway. For a time there were studios in

the area - for example, the Dutch Jewish artist Albert Alter was based

here. The flats on the corner [right] at the bottom of the hill are part of the 1989-90 development by Rick Mather, abutting Times House.

The

Artichoke Tavern stood on the corner of Artichoke Hill, at 19 St

George's Street [now 50 The Highway]; it was rebuilt in the mid-20th

century and later renamed The Caxton [left]; in 2012 it became a Domino's pizza takeaway. For a time there were studios in

the area - for example, the Dutch Jewish artist Albert Alter was based

here. The flats on the corner [right] at the bottom of the hill are part of the 1989-90 development by Rick Mather, abutting Times House.

(4) Chigwell Hill boasts one of London's earliest street signs (on the corner of The Highway). Pictured,

looking north towards The Highway, is a painting from 1881 and a

photograph from 1950 which shows little change. At the top is the

now-closed Old Rose public house.

(4) Chigwell Hill boasts one of London's earliest street signs (on the corner of The Highway). Pictured,

looking north towards The Highway, is a painting from 1881 and a

photograph from 1950 which shows little change. At the top is the

now-closed Old Rose public house.Footnote: The Highway in Roman Britain - and plans for the future

Until

recently Babe Ruth's - an art deco American restaurant with a

sports theme, once visited by Tony Blair [far left] - stood at 172-176 The

Highway, on the corner of Wapping Lane. This was demolished in 2002,

and prior to the building of the Eluna apartment block [left] pre-construct archaeology

was carried out, which later continued on the vacant lot

across the road, north of Tobacco Dock (with some photographs taken

from the church tower). This has uncovered evidence of a bath-house and

associated buildings dating from some time between the 2nd and 4th

centuries, which was written up in 2011 (Pre-Construct Archaeology, monograph no.12) [right]. The finds are now covered over, and planning permission for a hotel on this site was recently given.

Until

recently Babe Ruth's - an art deco American restaurant with a

sports theme, once visited by Tony Blair [far left] - stood at 172-176 The

Highway, on the corner of Wapping Lane. This was demolished in 2002,

and prior to the building of the Eluna apartment block [left] pre-construct archaeology

was carried out, which later continued on the vacant lot

across the road, north of Tobacco Dock (with some photographs taken

from the church tower). This has uncovered evidence of a bath-house and

associated buildings dating from some time between the 2nd and 4th

centuries, which was written up in 2011 (Pre-Construct Archaeology, monograph no.12) [right]. The finds are now covered over, and planning permission for a hotel on this site was recently given.

See here

for an account by Sir Robert Cotton of the discovery, in 1614 or 1615,

in Ratcliff Field of a monument to a Roman Proprætor's wife, which he

dated to 239 AD.

Back to History page