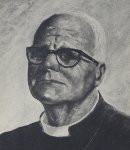

Father Joe - Joseph

Williamson MBE (1895-1988)

Father Joe - Joseph

Williamson MBE (1895-1988)

Joseph

Williamson was born at 75 Arcadia Street, Poplar, where his

widowed mother, on whom he doted all his life (calling her one of

nature's greatest ladies), brought up eight

children (three others died in infancy) in two rooms. She could not

read or write, and relied on one of her daughters to deal with

correspondence. The boys slept in

two beds in a tiny room; I can't

remember where the others slept.

When Joe was 3, his father had been crushed to death in the mud of East

India Docks in a shipbreaking accident, when a boiler collapsed. Mother

refused to let the younger children go to Langley House, the East

London orphanage, and never managed to qualify for charity despite

their desperate poverty since the children and their clothes were

always clean (Good Gawd, soap's cheap

enough, she said) and they had

boots - of a sort. She got by taking in mounds of washing and ironing,

and starved herself when food was short. But Joe insisted it was a

happy home, despite the fact that one brother was sent to a reformatory

(where he was unjustly birched) and two others later took refuge in

drink. He was rightly proud of his roots.

Joseph

Williamson was born at 75 Arcadia Street, Poplar, where his

widowed mother, on whom he doted all his life (calling her one of

nature's greatest ladies), brought up eight

children (three others died in infancy) in two rooms. She could not

read or write, and relied on one of her daughters to deal with

correspondence. The boys slept in

two beds in a tiny room; I can't

remember where the others slept.

When Joe was 3, his father had been crushed to death in the mud of East

India Docks in a shipbreaking accident, when a boiler collapsed. Mother

refused to let the younger children go to Langley House, the East

London orphanage, and never managed to qualify for charity despite

their desperate poverty since the children and their clothes were

always clean (Good Gawd, soap's cheap

enough, she said) and they had

boots - of a sort. She got by taking in mounds of washing and ironing,

and starved herself when food was short. But Joe insisted it was a

happy home, despite the fact that one brother was sent to a reformatory

(where he was unjustly birched) and two others later took refuge in

drink. He was rightly proud of his roots. After school, he

spent six months in service, as a page boy at Radlett

- hard work and good food, but he was sacked after six months. He then

worked as a clerk at Cubitts, and at the Civil Service Stores in

Haymarket, with a short spell working at the home of a suffragette in

Southminster, but this did not work out: he was too ready to speak his

mind, and, being short-sighted, was clumsy. (His eyesight remained a

problem all his life.) These posts had been arranged by Fr Dawson. His

successor, Fr Lambert, also took Joe under his wing and became a kind

of guardian. F.R. Barry (later

Bishop of Southwell) was his

chaplain for a time. Fr Joe

said in his autobigraphy that when he signed up for the Army in 1914,

serving in France, he found

the routine, and the regular food and pay, congenial, and missed it

when he was demobbed. However, in the (unpublished) first draft he says

that he hated his time in France and was terrified; he was bitter about

Earl Haig's command which ordered thousands of men 'over the top' to

their deaths, and considered him to be a criminal. He had great respect

for Philip 'Tubby'

Clayton and the help TocH brought to the troops, and for the

ministry of those like 'Woodbine Willie', the Revd Geoffrey

Studdart Kennedy, who stood up for the men against the officers and

the

system.

After school, he

spent six months in service, as a page boy at Radlett

- hard work and good food, but he was sacked after six months. He then

worked as a clerk at Cubitts, and at the Civil Service Stores in

Haymarket, with a short spell working at the home of a suffragette in

Southminster, but this did not work out: he was too ready to speak his

mind, and, being short-sighted, was clumsy. (His eyesight remained a

problem all his life.) These posts had been arranged by Fr Dawson. His

successor, Fr Lambert, also took Joe under his wing and became a kind

of guardian. F.R. Barry (later

Bishop of Southwell) was his

chaplain for a time. Fr Joe

said in his autobigraphy that when he signed up for the Army in 1914,

serving in France, he found

the routine, and the regular food and pay, congenial, and missed it

when he was demobbed. However, in the (unpublished) first draft he says

that he hated his time in France and was terrified; he was bitter about

Earl Haig's command which ordered thousands of men 'over the top' to

their deaths, and considered him to be a criminal. He had great respect

for Philip 'Tubby'

Clayton and the help TocH brought to the troops, and for the

ministry of those like 'Woodbine Willie', the Revd Geoffrey

Studdart Kennedy, who stood up for the men against the officers and

the

system.

In

1952 a friend put his name forward for St Paul Dock Street with

St Mark Whitechapel, saying 'It's about time you returned to London'.

(In later life, he often commented that he was never offered a parish

by a bishop, but only by patrons!) Though a 'Catholic' (but not in the

'party' sense - see below), he was appointed to what had been an

Evangelical church, and got to grips with the poverty and deprivation

of the area, and set about restoring the church. The ship's weathervane

which topped the spire was taken down for cleaning and regilding, and

he toured it round the parish on a cart fundraising.

In

1952 a friend put his name forward for St Paul Dock Street with

St Mark Whitechapel, saying 'It's about time you returned to London'.

(In later life, he often commented that he was never offered a parish

by a bishop, but only by patrons!) Though a 'Catholic' (but not in the

'party' sense - see below), he was appointed to what had been an

Evangelical church, and got to grips with the poverty and deprivation

of the area, and set about restoring the church. The ship's weathervane

which topped the spire was taken down for cleaning and regilding, and

he toured it round the parish on a cart fundraising.

Mindful of

his own childhood at St Saviour's, he

valued the fact that St Paul's had a church school, and had a

special care for it. Princess Margaret came to open the new school hall

in 1962. (Some years later, when St Paul's closed, the restored ship [pictured above] was

removed from the church spire and mounted on the outside wall of the

hall - appropriately, though without official permission, prompting a

firm rebuke from the then-Rector of St George's.) Six years earlier, in

1956, the Queen Mother had visited the parish on St George's Day to unveil a memorial

window to Admiral Woods.

Mindful of

his own childhood at St Saviour's, he

valued the fact that St Paul's had a church school, and had a

special care for it. Princess Margaret came to open the new school hall

in 1962. (Some years later, when St Paul's closed, the restored ship [pictured above] was

removed from the church spire and mounted on the outside wall of the

hall - appropriately, though without official permission, prompting a

firm rebuke from the then-Rector of St George's.) Six years earlier, in

1956, the Queen Mother had visited the parish on St George's Day to unveil a memorial

window to Admiral Woods.

He introduced a Good Friday walk of witness

through the streets (which became a deanery event). Cable

Street, a

thoroughfare that had become world-famous as a result of the riots 30

years ealier, and in his time had been taken over by a bewildering

variety of African and European all-night cafés, knocking

shops,

robber landlords and drug dealers, became a true Via Dolorosa. He

was a keen

visitor, and always ready (with Audrey's help, and that of his

now-adult children) to

welcome people into the vicarage. His son Tony (holding the cross in the second picture) was

ordained in 1961 and served as a worker priest (one of the relatively

few to make sense of this vocation), a Labour councillor and Diocesan

Director of Education for Oxford before his retirement. He and his

family revisited the area a few years ago to walk the streets and see how much

life has changed hereabouts, and visited the current occupants of the former Vicarage.

He introduced a Good Friday walk of witness

through the streets (which became a deanery event). Cable

Street, a

thoroughfare that had become world-famous as a result of the riots 30

years ealier, and in his time had been taken over by a bewildering

variety of African and European all-night cafés, knocking

shops,

robber landlords and drug dealers, became a true Via Dolorosa. He

was a keen

visitor, and always ready (with Audrey's help, and that of his

now-adult children) to

welcome people into the vicarage. His son Tony (holding the cross in the second picture) was

ordained in 1961 and served as a worker priest (one of the relatively

few to make sense of this vocation), a Labour councillor and Diocesan

Director of Education for Oxford before his retirement. He and his

family revisited the area a few years ago to walk the streets and see how much

life has changed hereabouts, and visited the current occupants of the former Vicarage.

He was appalled by, and documented, the slum housing conditions of the

parish, and wrote many letters to the authorities. He took on the slum

landlords who were rife in the area. He challenged Henry Brooke, the

housing minister, to walk round the parish with him - He would be sickened and

shocked. On one occasion, in his last year

at St Paul's, he even swallowed his ardent royalist and anti-communist

principles by encouraging church folk to vote for the atheist and

communist councillor Solly Kaye, after he had craftily saved Eileen

Mansions from falling into their hands. Pictured in

1962 are 28 Heneage Street (off Brick Lane) and the communal tap at 23

Cable Street; and Fr Joe talking to mothers in the street.

He was appalled by, and documented, the slum housing conditions of the

parish, and wrote many letters to the authorities. He took on the slum

landlords who were rife in the area. He challenged Henry Brooke, the

housing minister, to walk round the parish with him - He would be sickened and

shocked. On one occasion, in his last year

at St Paul's, he even swallowed his ardent royalist and anti-communist

principles by encouraging church folk to vote for the atheist and

communist councillor Solly Kaye, after he had craftily saved Eileen

Mansions from falling into their hands. Pictured in

1962 are 28 Heneage Street (off Brick Lane) and the communal tap at 23

Cable Street; and Fr Joe talking to mothers in the street.

But it was as the 'prostitute's padre' that he came into the public eye. He

was indignant, and outspoken, particularly in the monthly parish

magazine The Pilot, about

the rise of public indecency. This

was the era of the 1957 Wolfenden

Report (on human sexuality) and the 1959 Street

Offences Act

(which drew attention to the way in which girls, some of them very

young, were trapped into

'moral danger'). They operated from the many cafés and clubs

along Cable Street which flourished until they were demolished under

the Graces Alley Compulsory Purchase Order of 1963 (partly because of

Father Joe's campaigning). The pimps were Arab, Ghanaian, Nigerian,

Maltese

but many of the girls were Irish or Welsh. Pictured right is

the corner of Cable Street and Ensign Street; prostitutes and their

clients off Cable Street in the 1950s; and Fr Joe walking the parish.

But it was as the 'prostitute's padre' that he came into the public eye. He

was indignant, and outspoken, particularly in the monthly parish

magazine The Pilot, about

the rise of public indecency. This

was the era of the 1957 Wolfenden

Report (on human sexuality) and the 1959 Street

Offences Act

(which drew attention to the way in which girls, some of them very

young, were trapped into

'moral danger'). They operated from the many cafés and clubs

along Cable Street which flourished until they were demolished under

the Graces Alley Compulsory Purchase Order of 1963 (partly because of

Father Joe's campaigning). The pimps were Arab, Ghanaian, Nigerian,

Maltese

but many of the girls were Irish or Welsh. Pictured right is

the corner of Cable Street and Ensign Street; prostitutes and their

clients off Cable Street in the 1950s; and Fr Joe walking the parish. Assessment

Assessment How to assess his ministry? He was a faithful parish priest who had

proved the hierarchy wrong about his capabilities. He was much-loved by

many, and a source of exasperation to others. Fr Ken Leech, who worked

with him in the 1950s, commented (in a 2006 talk given at the merger of

UNLEASH and Housing Justice) Williamson,

like Josephine Butler, who inspired him, and about whom he wrote a

small book, used the language of 'rescue' constantly, yet he saw the

close link between prostitution and bad housing. He campaigned so

relentlessly against slum conditions that he got a good deal of his

parish neighbourhood demolished*. However, Williamson was not

politically astute, and often failed to make wider connections.

How to assess his ministry? He was a faithful parish priest who had

proved the hierarchy wrong about his capabilities. He was much-loved by

many, and a source of exasperation to others. Fr Ken Leech, who worked

with him in the 1950s, commented (in a 2006 talk given at the merger of

UNLEASH and Housing Justice) Williamson,

like Josephine Butler, who inspired him, and about whom he wrote a

small book, used the language of 'rescue' constantly, yet he saw the

close link between prostitution and bad housing. He campaigned so

relentlessly against slum conditions that he got a good deal of his

parish neighbourhood demolished*. However, Williamson was not

politically astute, and often failed to make wider connections.

* Bulldozers are the only way to clear Stepney of its shocking vice, Fr Joe said. In a 2010 lecture for the Heritage of London Trust

on 'This Unfortunate and Ignored Locality: the Lost Squares of Stepney'

Will Palin lamented that Fr Joe stigmatised the whole area, and did not

discriminate between the true slums and centres of prostitution, such as Sander

Street, photographed by Frank Rust [right in 1957, showing Edith Ramsay, and for this article of 1 March 1961 in the Daily Mail], and Wellclose and Prince's

Squares, in the vicinity of the church and its school, which could have

been saved and restored, as happened in parts of Spitalfields. With

hindsight, we can argue that a 'clean sweep' of these areas was the wrong

answer; but at the time there was little will to save these squares on

heritage grounds when social conditions were so desperate.

* Bulldozers are the only way to clear Stepney of its shocking vice, Fr Joe said. In a 2010 lecture for the Heritage of London Trust

on 'This Unfortunate and Ignored Locality: the Lost Squares of Stepney'

Will Palin lamented that Fr Joe stigmatised the whole area, and did not

discriminate between the true slums and centres of prostitution, such as Sander

Street, photographed by Frank Rust [right in 1957, showing Edith Ramsay, and for this article of 1 March 1961 in the Daily Mail], and Wellclose and Prince's

Squares, in the vicinity of the church and its school, which could have

been saved and restored, as happened in parts of Spitalfields. With

hindsight, we can argue that a 'clean sweep' of these areas was the wrong

answer; but at the time there was little will to save these squares on

heritage grounds when social conditions were so desperate. | AN AFTERTHOUGHT Was Father Joe aware that the first English home for work with prostitutes, the Magdalen Hospital, was based a short distance away from Church House, Wellclose Square from 1758 to 1769? Its underlying philosophy and methods were quite different, but it was just as much in the public eye. The comparisons are intriguing. A century later, a few yards away in the other direction, in Betts Street, there was also a 'Refuge and Receiving Home', established in 1879 for 'rescue and preventative work among girls and children'. This was run by the Bridge of Hope Mission and linked to 'cottage training homes' at Chingford, to which girls who had been abused or become pregnant were taken. Ministry to streetworkers continues in the East End, particularly at St Matthew Bethnal Green. |