Episcopal

Floating Church (1825-45)

Episcopal

Floating Church (1825-45)

Destitute Sailors' Asylum / Rest / Fund (1827-1941)

Sailors'

Home (1835-1974)

(The Fund, and Sailors' Home & Red Ensign Club, were removed from the Charities Register in 1992)

Note: The story of Anglican and nonconformist/non-denominational initiatives for the welfare of seamen (both Royal Navy and merchant), fishermen, lightermen, watermen and their dependents in the local area is an extremely complicated one, and for fuller details the standard work is Roald Kverndal's Seamen's Missions: Their Origin and Early Growth (1986), much of which can be read online. Kverndal, son-in-law of a pastor of the Norwegian Seamen's Church, worked in the shipping industry before becoming a seafarers' chaplain. He updates the story in The Way of the Sea: The changing shape of mission in the seafaring world (2008). Alston Kennerley, a research associate at the University of Plymouth, produced his doctoral thesis (1989, unpublished - available at the Mission to Seafarers) on 'British Seamen's Missions and Sailors' Homes: Voluntary Welfare Provision for Serving Seafarers, 1815-1970', based on minute books and other records. He has written specifically about local provisions in 'The Sailors' Home, London, and Seamen's Welfare, 1829-1974' in Maritime Mission Studies vol.1 (Spring 1998), pages 24-56, and drew the plan above of the various institutions. A more recent work, by a Roman Catholic, is R.W.H. Miller One Firm Anchor (Lutterworth 2012). See also this site about church ships (en français!)

Because many of the clergy who served these institutions had complex and interesting lives before and after their time here, some of them are recorded separately: follow the links below.

This trio of Anglican institutions was created to serve the various needs of the growing number of mariners working out of the Port of London. In Anglican terms, Captain R.J. Elliot was the prime motive force: they became his all-consuming life's work. But, as shown below, some of them originated in non-denominational projects innovated by others, such as the remarkable George Charles 'Bo'sun' Smith and Captain George Gambier and his brother (nephews of the Admiral), and he maintained working relationships with them even after throwing in his lot with the Anglican cause, despite tensions over the millenial Irvingite enthusiasms of Gambier, which Elliot shared to some degree for a time but Smith abhorred. His memorial in St Paul Dock Street, in gothic tabernacle style, reads

Charles Besley Gribble, the first minister of St Paul Dock Street and chaplain to the institutions, wrote The Naval Officer: a new creature in Christ Jesus, exemplified in the living and dying of Captain Robert James Elliot, R.N. (Nisbet 1849).

Each

institution had a separate committee of the great and the good, but

membership overlapped and their reports were presented together at

meetings held in Sackville Street W1. The chaplains were approved and

licensed by the Bishop of London. From time to time there was tension

between the three bodies, and unclarity over spiritual and pastoral

responsibility. The minute books are held at the National Maritime

Museum.

EPISCOPAL FLOATING CHURCH

In

July 1825 a meeting was held at the London Tavern, Bishopsgate,

presided over by the Lord Mayor, to consider the best means to

promote the spiritual welfare of the seamen and their families. The

London Episcopal Floating Church Society was created, and a chaplain

was appointed, assisted by two sailors, to visit the seafarers afloat

between London Bridge and the Pool, and their families on shore. A

suitable boat was provided, and two seamen engaged to assist the

chaplain. The Admiralty provided the ship Brazen,

a 26-gun ex sloop-of-war, latterly used as a convict ship, as a 'floating church'; it was adapted to

acommodate 500 hearers and

moored by Rotherhithe parish church.

The first service was

held on Good Friday, 24 March 1829. It capsized in 1832 (with no loss

of life) and after repairs was moved in 1834 to a new location on this side of the Thames, in the

Admiralty Tier off the Tower of London. A room was also hired at

Wapping,

for services and a Sunday School. King George IV became a patron,

contributing £50 a year – a commitment continued by

William

IV and (for a time) Queen Victoria.

In

July 1825 a meeting was held at the London Tavern, Bishopsgate,

presided over by the Lord Mayor, to consider the best means to

promote the spiritual welfare of the seamen and their families. The

London Episcopal Floating Church Society was created, and a chaplain

was appointed, assisted by two sailors, to visit the seafarers afloat

between London Bridge and the Pool, and their families on shore. A

suitable boat was provided, and two seamen engaged to assist the

chaplain. The Admiralty provided the ship Brazen,

a 26-gun ex sloop-of-war, latterly used as a convict ship, as a 'floating church'; it was adapted to

acommodate 500 hearers and

moored by Rotherhithe parish church.

The first service was

held on Good Friday, 24 March 1829. It capsized in 1832 (with no loss

of life) and after repairs was moved in 1834 to a new location on this side of the Thames, in the

Admiralty Tier off the Tower of London. A room was also hired at

Wapping,

for services and a Sunday School. King George IV became a patron,

contributing £50 a year – a commitment continued by

William

IV and (for a time) Queen Victoria.

It was not London's first 'floating chapel for seamen'. The non-denominational Ark (formerly HMS Swift) had been moored nearby since 1818: here (from The Christian Herald & Seaman's Magazine vol 8 p377) is a pious account from 1821 of a visit paid by a young sailor Samuel Newton. The

rationale was that sailors rarely visited churches on shore, but would

feel more comfortable worshipping in a vessel; initially it proved

an effective strategy, but see the comments of John Davis below. 'Floating churches' were established in other British ports.

The first permanent chaplain (1829-30) was the redoubtable James Hough who had been a missionary in India and was to write extensively about the history of Christianity in India (more details about his life and books here); but attendances on board the Floating Church were poor, and constant exposure to the river undermined his health, so he moved to become Perpetual Curate of Ham. He died in 1847.

His successor in late 1830, on a salary of £200 a year, was John Davis, who had been curate of Chesterfield. He also found conditions too strenuous for his health, and failed to increase attendance - he issued an ultimatum to 'the Seamen of the Port of London' ending I cannot, my dear brethren, preach without a congregation. Eventually he turned instead to prison work, chronicled here.From 1839 he was Chaplain of the Debtors' Prison, and from 1843 the Ordinary (= Chaplain) of Newgate, remaining there 22 years until his death in 1865, aged 65. Here he was much in the public eye, more than once mocked by Punch for his robust opinions on criminal justice.

Neville

Jones

was the next chaplain, in post from 1835(?) before becoming the

first minister of St Mark Whitechapel, where there is an account of his life.

His successor (1839-42) at the

Floating

Church and Sailors' Home (but not, it seems, the Asylum) was Sir

William Dunbar.

Attendances at the Floating Church did not

increase in his time either, and he resigned and moved to Scotland,

where he became embroiled in the 'Drummondite' controversy, as detailed

here.

So too did Alphonsus (aka Alphonse) William Henry Rose who followed him briefly in 1842 (and also, a few years later Charles Popham Miles and Charles Besley Gribble).

For the next appointment there were no less than 31 applicants, and it was agreed to give five of them a fortnight's trial. Charles Adam John Smith, was appointed, and served from 1843-47 - see here for more details, including one of his sermons. The Floating Church Society contributed £150 a year (despite being in debt), the Sailors' Home £100 and the Asylum £50.

As

early as 1836 the Annual

Report shows that Elliot was promoting, and finding patronage for,

an alternative 'Episcopal Chapel on shore'. The Brazen

was

decaying, traffic on the river had increased, causing 'Sabbath

desecration' and disturbing the services, and its mooring was under

threat. With the construction of the docks, working patterns had

changed: crews were no longer kept on board to unload cargoes, and

lived on shore with their families, or in boarding houses, or at the

Sailors' Home. In 1843 plans were laid to purchase the Danish Church,

and a fund was set up - the Floating Church's debts had reduced, making

a merger possible. But instead it was decided to build a new church, St Paul's Church for Seamen,

which was consecrated in 1847. The

final services on board the Brazen

were in 1845, and it was broken up.

Things have come full circle, for the nearby parish of St Anne Limehouse now runs St Peter's Barge, a floating church in West India Quay to minister to those who live and work in Canary Wharf - though in somewhat different circumstances!

DESTITUTE

SAILORS' ASYLUM / REST / FUND

The

Asylum opened

in 1827, originally at 19 Wellclose Square, and then in a former warehouse in Dock Street, with bread and

soup in the basement and straw-filled bunks in the upper stories for sleeping

quarters. Bo'sun Smith was the instigator, but Elliot and the Gambier brothers were

closely involved in its running. In 1836 a more permanent base was created at 23

Well [now Ensign] Street - drawing c1855 - and the Rest (as it was now called) was run in conjuction with the Home (below).

The

Asylum opened

in 1827, originally at 19 Wellclose Square, and then in a former warehouse in Dock Street, with bread and

soup in the basement and straw-filled bunks in the upper stories for sleeping

quarters. Bo'sun Smith was the instigator, but Elliot and the Gambier brothers were

closely involved in its running. In 1836 a more permanent base was created at 23

Well [now Ensign] Street - drawing c1855 - and the Rest (as it was now called) was run in conjuction with the Home (below).

Its purpose was to

provide shelter and

relief, with food and clothing, for distressed seafarers of all

nations who had not left their last ship more than a year, and to

assist them to find work.The old and infirm had their passages home paid for, and others were

helped to get into hospitals and infirmaries around London. Morning

and evening prayers, and the Scriptures, were regularly read, with a

sermon every evening at 7pm. A discharge-ticket from the

Dreadnought

Hospital Ship at Greenwich was an automatic passport into the asylum.

(In 1821 the Grampus had

been moored off Greenwich as a floating hospital offering treatment to

any sick seaman of any nationality 'on presenting himself alongside',

solely on the basis of 'his own apparent condition'; it was replaced by

the larger Dreadnought, Collingwood's flagship from Trafalgar, from 1831-57 - right - and an onshore hospital was built in 1870.)

Its purpose was to

provide shelter and

relief, with food and clothing, for distressed seafarers of all

nations who had not left their last ship more than a year, and to

assist them to find work.The old and infirm had their passages home paid for, and others were

helped to get into hospitals and infirmaries around London. Morning

and evening prayers, and the Scriptures, were regularly read, with a

sermon every evening at 7pm. A discharge-ticket from the

Dreadnought

Hospital Ship at Greenwich was an automatic passport into the asylum.

(In 1821 the Grampus had

been moored off Greenwich as a floating hospital offering treatment to

any sick seaman of any nationality 'on presenting himself alongside',

solely on the basis of 'his own apparent condition'; it was replaced by

the larger Dreadnought, Collingwood's flagship from Trafalgar, from 1831-57 - right - and an onshore hospital was built in 1870.)

The Asylum helped about 1500 men a year, and had a good track record of enabling them to find work. A contemporary commentator said its arrangements are well worth imitation in lodgings for the lowest class, such as ragged school boys, and common beggars - a description of lodging-house much needed, and which has not yet, as far as we know, entered into the plans of either of the great societies now in operation.

The

Rest (but not the Home) closed in 1882 when new premises were opened in

Gravesend, which were handed over the the government during the First

World War and afterwards were sold to the Shipping Federation for their

new sea school. But the need for free accommodation for destitue

seamen, alongside those who paid modest rent at the Home, remained, and

the Lord Charles Beresford Memorial Rest was

created nearby in 1923 providing free board and lodging for 34 men,

with funding from the British Ambulance Committee and friends of Admiral Lord Beresford of Metemeh.

An extension providing twelve additional beds was opened in 1931 by

Prince George and blessed by the Bishop of Stepney. By then known as

the Destitute Sailors' Fund,

it had assisted over 139,000 seamen in the course of its history. Times

were hard, with recession; there were many ships lying idle (two cargo

lines which had run 54 ships were reduced to a handful), and they had

even had masters and officers applying for admission. Funding the work

was also hard - only £600 of the £3,000 cost of the extension had been

raised - and they depended on help given by the King George's Fund for

Sailors. The buildings were bomb-damaged in 1941, and men

were accommodated at the Home; from 1947, the funds were used to assist

those in special temporary need, via the Salvation Army and other

institutions, and with small grants for food and clothing.

THE SAILORS' HOME

Alongside

his many other projects, Bo'sun Smith was keen to

create a large depot to provide comfortable and cheap board and

lodging for seafarers and apprentices between voyages, and to address

the evils of the crimping system which was rampant at the time, whereby

middlemen guaranteed to find crew for a ship and took a massive cut

from the sailors whom they lured into their clutches by providing cheap

lodgings, food and loans, leaving them with huge debts. His plan had

various other aspects for their welfare, most of which came to

fruition.

The moment of

opportunity came when the Royal Brunswick Theatre in Well [now Ensign]

Street collapsed on 28 February 1828 [left]. It had only just re-opened after rebuilding - see here

for more details. Smith - who had previously pressed magistrates and

Tower Hamlets authorities to keep the site as an ornament, rather than

a disgrace to Wellclose Square - was one of the first on the scene, and

took

command, summoning every man from the Destitute Sailors' Asylum to

assist in digging out the dead and wounded, and supervising the

operations throughout the day. While he lamented the loss of

life, henceforth he saw this as a sign of divine judgement and

providence - God will not have a sailors' playhouse in Well Street. Much

publicity, with tracts and meetings, ensued, and in 1829 a committee

was established (with William Wilberforce one of the signatories of the

trust deed) to establish a Sailors' Home or Royal Brunswick Maritime Establishment. (The latter part of the title was later dropped, but the distinctive bollards which remain in the area, marked 'RBT' [right] date

from this time. For those interested in London bollards, see this comprehensive site.) Smith acquired the freehold, and seamen helped lay the

first bricks; but in the event by the time it opened in 1835 Smith -

having suffered various personal reverses, noted here - had (willingly, it seems) transferred ownership and management to the Church of England, under Elliot's leadership.

The moment of

opportunity came when the Royal Brunswick Theatre in Well [now Ensign]

Street collapsed on 28 February 1828 [left]. It had only just re-opened after rebuilding - see here

for more details. Smith - who had previously pressed magistrates and

Tower Hamlets authorities to keep the site as an ornament, rather than

a disgrace to Wellclose Square - was one of the first on the scene, and

took

command, summoning every man from the Destitute Sailors' Asylum to

assist in digging out the dead and wounded, and supervising the

operations throughout the day. While he lamented the loss of

life, henceforth he saw this as a sign of divine judgement and

providence - God will not have a sailors' playhouse in Well Street. Much

publicity, with tracts and meetings, ensued, and in 1829 a committee

was established (with William Wilberforce one of the signatories of the

trust deed) to establish a Sailors' Home or Royal Brunswick Maritime Establishment. (The latter part of the title was later dropped, but the distinctive bollards which remain in the area, marked 'RBT' [right] date

from this time. For those interested in London bollards, see this comprehensive site.) Smith acquired the freehold, and seamen helped lay the

first bricks; but in the event by the time it opened in 1835 Smith -

having suffered various personal reverses, noted here - had (willingly, it seems) transferred ownership and management to the Church of England, under Elliot's leadership.

Initially it provided 100 berths (1835 façade pictured in the Nautical Magazine vol 17); in 1848 it was enlarged for 328 (illustration from the British Workman

of 1857), and again in 1865 for 500, by which time it was

accommodating between 4000 and 5000 men a year. Horse-drawn vans, in

charge of tough drivers, met ships to bring sailors and their kit to

the Home - in the face of opposition, and occasional violence, from

boarding-house keepers' scouts. Each man had a

separate 'berth', arranged round a central hall (as in a prison), and

the original all-inclusive rates were 2s. a day

(apprentices 1s. 6d. a day, 'other lads' 12s. a week). It was the first

of its kind, and became a widely-copied model. In 1843 a free evening

school, teaching reading, writing, arithmetic and navigation was

opened, and enlarged in 1851 at the request of the Board of Trade, with

a government grant. Domestic comforts,

including 'proper' books, were provided, and the chaplain

led worship each day. It also provided a banking service for

residents, protecting them from 'crimping' (local gangs

defrauding

on-shore sailors of their pay) and helping them to save their earnings.

It was also an alcohol-free zone.

Initially it provided 100 berths (1835 façade pictured in the Nautical Magazine vol 17); in 1848 it was enlarged for 328 (illustration from the British Workman

of 1857), and again in 1865 for 500, by which time it was

accommodating between 4000 and 5000 men a year. Horse-drawn vans, in

charge of tough drivers, met ships to bring sailors and their kit to

the Home - in the face of opposition, and occasional violence, from

boarding-house keepers' scouts. Each man had a

separate 'berth', arranged round a central hall (as in a prison), and

the original all-inclusive rates were 2s. a day

(apprentices 1s. 6d. a day, 'other lads' 12s. a week). It was the first

of its kind, and became a widely-copied model. In 1843 a free evening

school, teaching reading, writing, arithmetic and navigation was

opened, and enlarged in 1851 at the request of the Board of Trade, with

a government grant. Domestic comforts,

including 'proper' books, were provided, and the chaplain

led worship each day. It also provided a banking service for

residents, protecting them from 'crimping' (local gangs

defrauding

on-shore sailors of their pay) and helping them to save their earnings.

It was also an alcohol-free zone.

Admiral Sir Jahleel Brenton, Bart, KCB, Lieutenant Governor of Greenwich Hospital, offered this testimonial: No institutions perhaps that ever sprung from the benevolence or wisdom of man, are more likely to be successful than the Destitute Sailors' Asylum, and the Sailors' Home - the latter especially as prevention is better than cure.

From 1837-39 the Chaplain of the Home (also curate of

St Anne Limehouse) was Charles Popham

Miles, whose story is here.

Left

is the ground floor Bombay or Calcutta dormitory of the Home (Pictorial Times

November 1846). In

one of the annual reports, Captain Elliot said The Sailors'

Home

was established to preserve sailors from the temptations and

depredations to which they are exposed in London on returning from

sea. Sailors are often to be seen wandering about the streets in

rags; and this was because they had no place to go to with safety to

themselves on coming ashore. A home was the very thing a sailor

wanted.... I heartily approve of these institutions, and if I had

arguments at command I would use all I could find to induce Christian

ladies and gentlemen to support them. In a national view they are

incalculably advantageous to the country. The Sailors' Home is a kind

of nursery for good seamen, and the country is at present very much

in want of good seamen, and it is impossible to say how soon that

want might be considerably increased. This

was a reference to the growing pattern of English sailors finding

work with ships of other nations, especially the USA.

Left

is the ground floor Bombay or Calcutta dormitory of the Home (Pictorial Times

November 1846). In

one of the annual reports, Captain Elliot said The Sailors'

Home

was established to preserve sailors from the temptations and

depredations to which they are exposed in London on returning from

sea. Sailors are often to be seen wandering about the streets in

rags; and this was because they had no place to go to with safety to

themselves on coming ashore. A home was the very thing a sailor

wanted.... I heartily approve of these institutions, and if I had

arguments at command I would use all I could find to induce Christian

ladies and gentlemen to support them. In a national view they are

incalculably advantageous to the country. The Sailors' Home is a kind

of nursery for good seamen, and the country is at present very much

in want of good seamen, and it is impossible to say how soon that

want might be considerably increased. This

was a reference to the growing pattern of English sailors finding

work with ships of other nations, especially the USA.

Here

is an extract from one of Henry Mayhew's Morning Chronicle

Letters (XLVII, 11 April 1850) about the Sailors' Home, and other

accommodation.

The 1851 Mercantile Marine Act (whose provisions are discussed here) established Mercantile Marine Offices in UK ports, and (recognising the pioneering work done here) provided that The Board of Trade may appoint any Superintendent of any Sailors' Home in the Port of London to be a Superintendent, and may appoint an Office in any such home to be a Mercantile Marine Office. Such an office was located in the Sailors' Home from 1853 to 1873, when it moved to Tower Hill for the next twenty years. The 1854 Merchant Shipping Act further provided that engagement of seamen for foreign trade voyages must take place before a Superintendent, and laid down rules (based on observation of the Home's practice) to ensure that at the end of a voyage wages were properly accounted for and received. The Secretary of the Home was appointed a Superintendent.

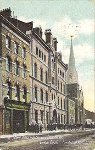

When the Home was extended in 1865 (as noted above) its main entrance was on Dock

Street, next to St Paul's vicarage and church, as seen in this

drawing from the Illustrated Times of 27 May 1865, and two versions of a later photograph. The polychromatic frontage was by E.L. Bracebridge and his pupil T.W. Fletcher. Charles

Dickens Jnr's 1883 edition of his Dictionary of the Thames describes

its work in this

period.

In 1893 a wing at the rear was demolished to make space for a new

Mercantile Marine Office

and Examination Rooms at 18 Ensign Street (designed by Wigg, Oliver & Hudson, right); this was rented by the Board of

Trade. Because this was where crews signed on, the Shipping Federation

and National Union of Seamen located their offices opposite. [It was converted into flats 1999 - note again the distinctive bollards, right].

When the Home was extended in 1865 (as noted above) its main entrance was on Dock

Street, next to St Paul's vicarage and church, as seen in this

drawing from the Illustrated Times of 27 May 1865, and two versions of a later photograph. The polychromatic frontage was by E.L. Bracebridge and his pupil T.W. Fletcher. Charles

Dickens Jnr's 1883 edition of his Dictionary of the Thames describes

its work in this

period.

In 1893 a wing at the rear was demolished to make space for a new

Mercantile Marine Office

and Examination Rooms at 18 Ensign Street (designed by Wigg, Oliver & Hudson, right); this was rented by the Board of

Trade. Because this was where crews signed on, the Shipping Federation

and National Union of Seamen located their offices opposite. [It was converted into flats 1999 - note again the distinctive bollards, right].

Between 1878 and 1894 the

writer Joseph

Conrad stayed at the Home many times as the seaman

Józef

Korzeniowski, and admired the institution: in his Notes

on Life and Letters

he wrote I have

been in

touch

with the Sailors’ Home for sixteen years of my life, off and

on...

I would say that, for seamen, the Well Street Home was a friendly

place. [Full text here.] An article by Alston Kennerley [mentioned above],

'Joseph Conrad at the London Sailors' Home', was published in The Conradian,

vol.33, no.1 (Spring 2008), pages 70-102.

Between 1878 and 1894 the

writer Joseph

Conrad stayed at the Home many times as the seaman

Józef

Korzeniowski, and admired the institution: in his Notes

on Life and Letters

he wrote I have

been in

touch

with the Sailors’ Home for sixteen years of my life, off and

on...

I would say that, for seamen, the Well Street Home was a friendly

place. [Full text here.] An article by Alston Kennerley [mentioned above],

'Joseph Conrad at the London Sailors' Home', was published in The Conradian,

vol.33, no.1 (Spring 2008), pages 70-102.

The

training programmes continued - Newton's

Navigation School ran until not long before the First

World War, and from 1893

the Home housed the London

School of Nautical Cookery,

in conjuction with the London County Council. The 1906 Merchant

Shipping Act made it compulsory for all British foreign-going ships to

carry a certificated cook, and the school was enlarged to meet the

extra demand. Over the years it trained 10,400 cooks for

the Merchant Navy, playing a key part in raising standards of feeding,

particularly on cargo ships. Its work was later integrated into the

LCC's further education programme. Also, from

1895-1958 the Shipwrecked Fishermen and Mariners' Society rented a room

at the Home. In the inter-war years Commander A.E. Loder RNR was the

Secretary.

For

two hundred years there had been a steady trickle of lascars - sailors

from Africa, China, the Malay archipelago and Bangladeshis

from

the Sylhet region who staffed British trading vessels - who jumped ship

at 'Tiger Bay', as Shadwell was known (see this

article from 1874). By 1940 they made up a quarter

of the Merchant Navy. Many of them served in the Second World War,

doing the lowliest jobs on board ship. See here

for early 19th century reactions to their presence in this area.

The

Home continued in existence under the name The Sailor's

Home and Red Ensign Club.

To provide better facilities, the Dock Street part of the site

was rebuilt

between 1951-61 to designs by Brian O'Rorke and Colin Murray with a brick-faced

5-storey block - right, beyond the church -

though they only completed the street range and stair tower, rather

than the whole building, as planned. But with the demise of

the

British merchant fleet the need for such accommodation declined, and in

financial difficulties it

closed on New Year's Eve 1974. Under the name of Beacon House, and then

Look Ahead Hostel, the buildings provided accommodation for homeless

and vulnerable individuals until 2012; presumably it will now become

apartments. The Ensign Youth Club in Wellclose Square (adjacent to St

Paul's School) perpetuates the name, though is currently a somewhat

forlorn building, used during the day as a private Muslim school.

The

Home continued in existence under the name The Sailor's

Home and Red Ensign Club.

To provide better facilities, the Dock Street part of the site

was rebuilt

between 1951-61 to designs by Brian O'Rorke and Colin Murray with a brick-faced

5-storey block - right, beyond the church -

though they only completed the street range and stair tower, rather

than the whole building, as planned. But with the demise of

the

British merchant fleet the need for such accommodation declined, and in

financial difficulties it

closed on New Year's Eve 1974. Under the name of Beacon House, and then

Look Ahead Hostel, the buildings provided accommodation for homeless

and vulnerable individuals until 2012; presumably it will now become

apartments. The Ensign Youth Club in Wellclose Square (adjacent to St

Paul's School) perpetuates the name, though is currently a somewhat

forlorn building, used during the day as a private Muslim school.

From

1933 to 1954 the Chaplain of the Red Ensign Club and honorary curate

of St

Paul's Dock Street was Alexander

Riall Wadham Woods.

Vice-Admiral Woods DSO was born in 1880, son of an admiral, and during

World War I was captain in charge of signals for the Grand Fleet of the

Royal Navy, under the command of Admiral Sir John Jellicoe - the only man on either side who could lose the war in an afternoon, said Churchill). 'Sammy' Woods (as he was known in the Navy) had a key role in the Battle of Jutland [right] on

31 May - 1 June 1916. The Germans were seeking to break the British

blockade of Germany, which had begun in 1914, and it fell to Captain

Woods to co-ordinate the movements of 151 craft - 28 battleships, 9

battle cruisers, 8 armoured cruisers, 26 light cruisers, 78 destroyers,

a mine-layer and a seaplane carrier. Signalling - much of it by flag or

shuttered searchlight, with sonar, wireless telegraphy and radio in

their infancy - was crucial, and slow. In years to come, he said that

at the height of the battle, alongside Jellicoe's telegraphic orders,

he had received a personal call from God: an interposed signal which came through from no earthly captain but from a higher command. He

kept his nerve, and maintained the fleet's formation. Who 'won' this

battle? The blockade remained in place (continuing until after the war,

becoming one of the factors humiliating Germany into the Treaty of

Versailles), but at a high cost: the British lost

6,094 men, with 510 wounded and 177 captured; 3 battle cruisers, 3

armoured cruisers and 8 destroyers. German losses were lighter: 2,551

men, with 507 wounded; a pre-dreadnought, a battlecruiser, 4

light cruisers and 5 torpedo boats.

From

1933 to 1954 the Chaplain of the Red Ensign Club and honorary curate

of St

Paul's Dock Street was Alexander

Riall Wadham Woods.

Vice-Admiral Woods DSO was born in 1880, son of an admiral, and during

World War I was captain in charge of signals for the Grand Fleet of the

Royal Navy, under the command of Admiral Sir John Jellicoe - the only man on either side who could lose the war in an afternoon, said Churchill). 'Sammy' Woods (as he was known in the Navy) had a key role in the Battle of Jutland [right] on

31 May - 1 June 1916. The Germans were seeking to break the British

blockade of Germany, which had begun in 1914, and it fell to Captain

Woods to co-ordinate the movements of 151 craft - 28 battleships, 9

battle cruisers, 8 armoured cruisers, 26 light cruisers, 78 destroyers,

a mine-layer and a seaplane carrier. Signalling - much of it by flag or

shuttered searchlight, with sonar, wireless telegraphy and radio in

their infancy - was crucial, and slow. In years to come, he said that

at the height of the battle, alongside Jellicoe's telegraphic orders,

he had received a personal call from God: an interposed signal which came through from no earthly captain but from a higher command. He

kept his nerve, and maintained the fleet's formation. Who 'won' this

battle? The blockade remained in place (continuing until after the war,

becoming one of the factors humiliating Germany into the Treaty of

Versailles), but at a high cost: the British lost

6,094 men, with 510 wounded and 177 captured; 3 battle cruisers, 3

armoured cruisers and 8 destroyers. German losses were lighter: 2,551

men, with 507 wounded; a pre-dreadnought, a battlecruiser, 4

light cruisers and 5 torpedo boats.

He

was awarded the DSO for his bravery under fire, and for a second time

the following year, as second in command of HMS Topaze in 1917,

when he

led a landing party to silence Turkish shore batteries at Salif (in

what is now the Yemen). He served out his time in the Navy, rising to

the rank of Rear Admiral, but turned down a further commission in 1931,

when at the age of 50 he followed his 'higher command' and, despite

suffering with muscular dystrophy, spent two years training for ordination, and chose to spent the rest

of his days in a docklands parish working with and befriending seafarers.

| In 1934 a young insurance clerk, John Scott, met ‘Father’ Woods at the Seamen’s Mission, and was taught morse and semaphore by him to qualify for his Scout and Sea Cadet signal badge. Scott was thinking of leaving his office desk and was undecided whether to go to sea or become a priest. ‘Combine both vocations,’ was Woods’ advice, ‘become a sailor and a naval chaplain.’ With Woods’ encouragement Scott joined the Navy in 1941, started training as an ordinary telegraphist, but a few months later had the opportunity to take his final exams for ordination. He became a Chaplain in the Royal Navy, and will be well known to many communicators, as he served for some years at the Signal School, and became Honorary Chaplain to the Royal Naval Communication Chiefs’ Association. Signal! A History of Signalling in the Royal Navy (Barrie H. Kent 2004) p323 |

'Admiral

Woods' was a respected figure in the parish, but was reticent about the

details of his naval career, and was dubbed by some 'the shy parson'.

Lil Mountain, a parishioner at St George-in-the-East, remembers his

visits to St Paul's School, where she was a pupil: they held him in

awe, and were instructed to curtsey to him in the street! He

lived on the top floor of the vicarage, and rarely claimed his honorary

stipend of £5 a year; he

died at the Home on All Saints' Day 1954, aged 74 - the 21st

anniversary of his curacy [funeral right]. Arthur

Calder-Marshall wrote a memoir, under the title No

Earthly Command: Being an enquiry into the life of Vice-Admiral the

Reverend Alexander Riall Wadham Woods DSO and bar, who during the

Battle of Jutland while Signals Officer received an 'Interposed

Message' telling him to serve God (London,

Hart-Davis 1957). The Queen Mother visited the parish on St George's Day 1956 to unveil a memorial plaque and window.

'Admiral

Woods' was a respected figure in the parish, but was reticent about the

details of his naval career, and was dubbed by some 'the shy parson'.

Lil Mountain, a parishioner at St George-in-the-East, remembers his

visits to St Paul's School, where she was a pupil: they held him in

awe, and were instructed to curtsey to him in the street! He

lived on the top floor of the vicarage, and rarely claimed his honorary

stipend of £5 a year; he

died at the Home on All Saints' Day 1954, aged 74 - the 21st

anniversary of his curacy [funeral right]. Arthur

Calder-Marshall wrote a memoir, under the title No

Earthly Command: Being an enquiry into the life of Vice-Admiral the

Reverend Alexander Riall Wadham Woods DSO and bar, who during the

Battle of Jutland while Signals Officer received an 'Interposed

Message' telling him to serve God (London,

Hart-Davis 1957). The Queen Mother visited the parish on St George's Day 1956 to unveil a memorial plaque and window.

Canon Walter Crooks wrote of him in 1990 (in a letter to Frank Rust) Just imagine my feelings of anxiety on being appointed to that parish having recently been demobbed from the Navy as a very young padre and knowing that my curate would be a former Admiral, a Flag Lieutenant to Earl Jellicoe at Jutland and old enough to be my grandfather! However, daunting though the prospect was, it took but a very short time to rejoice in the fact that here I had a teacher in the greatest things of life - spirituality and love for people.

In

2002, after St Paul's Church closed, his ashes were transferred to the

Crouch family grave, together with those of Elizabeth Crouch. The

Crouches had played a central part in the life of St Paul's (Elizabeth,

who worshipped there until the 1960s, was probably the last survivor of

the Clothed Scholars), and

Admiral Woods was a family friend.